From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

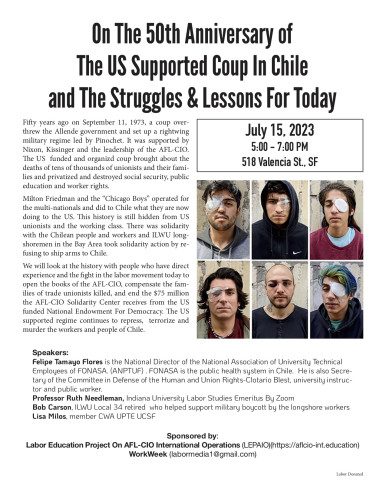

Panel: 50th Anniversary of US Supported Coup In Chile & The Struggles & Lessons Today

Date:

Saturday, July 15, 2023

Time:

5:00 PM

-

7:30 PM

Event Type:

Speaker

Organizer/Author:

Labor Ed Project on AFL-CIO Int'l Operations

Location Details:

Eric Quezada Center for Culture & Politics

518 Valencia St

San Francisco

518 Valencia St

San Francisco

Fifty years ago on September 11, 1973, a coup overthrew the Allende government and set up a rightwing military regime led by Pinochet. It was supported by Nixon, Kissinger and the leadership of the AFL-CIO. The US funded and organized coup brought about the deaths of tens of thousands of unionists and their families and privatized and destroyed social security, public education and worker rights.

Milton Friedman and the “Chicago Boys” operated for the multi-nationals and did to Chile what they are now doing to the US. This history is still hidden from US unionists and the working class. There was solidarity with the Chilean people and workers and ILWU long- shoremen in the Bay Area took solidarity action by refusing to ship arms to Chile.

We will look at the history with people who have direct experience and the fight in the labor movement today to open the books of the AFL-CIO, compensate the families of trade unionists killed, and end the $75 million the AFL-CIO Solidarity Center receives from the US funded National Endowment For Democracy. The US supported regime continues to repress, terrorize and murder the workers and people of Chile.

Speakers:

Felipe Tamayo Flores is the National Director of the National Association of University Technical Employees of FONASA. (ANPTUF) . FONASA is the public health system in Chile. He is also Secretary of the Committee in Defense of the Human and Union Rights- Clotario Blest, university instructor and public worker.

Professor Ruth Needleman, Indiana University Labor Studies Emeritus By Zoom

Bob Carson, ILWU Local 34 retired who helped support military boycott by the longshore workers

Lisa Milos, member CWA UPTE UCSF

Sponsored by:

Labor Education Project On AFL-CIO International Operations (LEPAIO)

(https://aflcio-int.education)

info [at] aflcio-int.education

WorkWeek,UFCLP

Milton Friedman and the “Chicago Boys” operated for the multi-nationals and did to Chile what they are now doing to the US. This history is still hidden from US unionists and the working class. There was solidarity with the Chilean people and workers and ILWU long- shoremen in the Bay Area took solidarity action by refusing to ship arms to Chile.

We will look at the history with people who have direct experience and the fight in the labor movement today to open the books of the AFL-CIO, compensate the families of trade unionists killed, and end the $75 million the AFL-CIO Solidarity Center receives from the US funded National Endowment For Democracy. The US supported regime continues to repress, terrorize and murder the workers and people of Chile.

Speakers:

Felipe Tamayo Flores is the National Director of the National Association of University Technical Employees of FONASA. (ANPTUF) . FONASA is the public health system in Chile. He is also Secretary of the Committee in Defense of the Human and Union Rights- Clotario Blest, university instructor and public worker.

Professor Ruth Needleman, Indiana University Labor Studies Emeritus By Zoom

Bob Carson, ILWU Local 34 retired who helped support military boycott by the longshore workers

Lisa Milos, member CWA UPTE UCSF

Sponsored by:

Labor Education Project On AFL-CIO International Operations (LEPAIO)

(https://aflcio-int.education)

info [at] aflcio-int.education

WorkWeek,UFCLP

For more information:

https://aflcio-int.education

Added to the calendar on Tue, Jul 4, 2023 2:33PM

Add Your Comments

Comments

(Hide Comments)

Memories of Chile On The 49th Anniversary Of The US AFL-CIO Supported Coup

By Ruth Needleman

https://portside.org/2017-07-03/memories-chile

As I watch current events in Venezuela, I am haunted by memories of Chile. I lived in Chile from July 1972 until February 1973, while socialist Salvador Allende was president.

I left Chile months before the fascist coup, although I had planned to return. That door closed.

Nonetheless I was there for the banging of pots and pans, the incredible shortages, the right-wing mobilizations, and in particular, the entrepreneurial strike of October 1972. Maduro is not Allende, and Venezuela is not Chile. Forty-four years and radically changing conditions separate them. Yet we are living a period of right-wing backlash and government takeovers, not unlike the sixties and seventies in Latin America.

I am haunted by memories because of the similarities in the right-wing opposition tactics. I came to know them intimately, in large part because after the October 1972 strike. I researched the right-wing opposition to Allende as part of a volunteer job I was doing at Quimantu, the National Publishing House. After I completed a chronology for a book Quimantu was doing, I began to interview the right-wing leaders of the opposition.

I started with the truck owner Vilarin but got introduced up the line to the president of SOFOFA, Orlando Saenz, the National Association of Manufacturers and the fascist-led Agricultural Society, Benjamin Matte, among others.

At the time I was on sabbatical from UC Santa Cruz where I had just established a Latin American Studies program. I presented myself as a sympathetic gringa to the leaders who would lay the foundations for the military coup. One thing never left my mind. Orlando Saenz, the head of SOFOFA, explained to me that he was grateful for Allende because now they knew everyone who would have to be killed.

In the course of my interviews I realized that these opposition leaders thought I was CIA and ready to bring more funds to them. But this is not the reason I am haunted. It is the similarities in opposition developments.

The Shortages: If you were poor, you had access to what was called “the popular basket,” cesta popular, that included basic foods, cooking oil, matches and toilet paper. If you were rich, you had all these things from the black market. I was neither, and therefore found life quite hard. Without cooking oil, it was hard to cook, but even harder if you had no matches to light the stove. What was particularly annoying, however, was the lack of toilet paper. I soon concluded that if you want to turn the middle classes against a government, just take away their toilet paper. The owner of El Mercurio, the main conservative newspaper, owned the paper company. (He was also international vice-president of Pepsi Cola.) The UP (Popular Unity Government) discovered tens of thousands of rolls of toilet paper thrown into the Mapuche River. It was, in fact, part of the strategic boycott.

US Economic Blockade: The US economic blockade, for example, prevented any bus parts from arriving in Chile. The shortage of buses made travel in Santiago almost impossible. The country was using volkswagon mini-buses and anything with wheels to transport people. Buses would pass and there was not even a window you could hang onto. People were out the door holding each others’ waists. As they were doing to Cuba, the US did to Chile. No aid, no trade, no imports, no exports.

Street Mobilizations: Then the pots and pans in the upper middle class barrio took to the streets, causing disruptions and general chaos.

President Allende did not respond with repression. In fact, he was convinced that the military in Chile was and would always be a supporter of democracy. He was wrong.

Pinochet was the US front man, preparing for a brutal military takeover. Training of Chilean military in Panama increased, as did US military funding. Training of right-wing trade unionists increased, done by the AFL-CIO’s international arm, the American Institute for Free Labor Development (AIFLD). I know this because I went to AIFLD’s training center and wrote down the names of Chilean students who attended over the two years preceding the coup. They were, for the most part, opposition leaders; some worked as agents turning in names of democratic union leaders so they could be rounded up and killed.

Allende decided to disarm rather than arm the masses, to placate Pinochet. The industrial strips outside of the capital were controlled by the workers and their unions. The workers were asked to disarm to show the world that Chile was on the road to socialism peacefully.

But the most lasting and gut-wrenching lesson I learned was that the ruling class was as class conscious as the working class, but with all the resources of the US behind them. That has been the case more recently in Brazil and Argentina. It is currently the case in Venezuela. The ruling class took revenge. What can the government of Venezuela do to resist? I do not know. What I do know is that an armed and conscious ruling class is a lethal and immensely powerful weapon.

There are many lessons I learned from my Chilean experiences, but the class consciousness of the 1% stood out. I lost many friends and two US co-workers in that coup on September 11, 1973. The book I contributed to, by the way, Los gremios patronales, was published on September 10, 1973. One copy was mailed to me. The rest were burned after September 11th.

Ruth Needleman, professor emerita, Indiana University

Memories of Chile On The 49th Anniversary Of The US AFL-CIO Supported Coup

By Ruth Needleman

https://portside.org/2017-07-03/memories-chile

As I watch current events in Venezuela, I am haunted by memories of Chile. I lived in Chile from July 1972 until February 1973, while socialist Salvador Allende was president.

I left Chile months before the fascist coup, although I had planned to return. That door closed.

Nonetheless I was there for the banging of pots and pans, the incredible shortages, the right-wing mobilizations, and in particular, the entrepreneurial strike of October 1972. Maduro is not Allende, and Venezuela is not Chile. Forty-four years and radically changing conditions separate them. Yet we are living a period of right-wing backlash and government takeovers, not unlike the sixties and seventies in Latin America.

I am haunted by memories because of the similarities in the right-wing opposition tactics. I came to know them intimately, in large part because after the October 1972 strike. I researched the right-wing opposition to Allende as part of a volunteer job I was doing at Quimantu, the National Publishing House. After I completed a chronology for a book Quimantu was doing, I began to interview the right-wing leaders of the opposition.

I started with the truck owner Vilarin but got introduced up the line to the president of SOFOFA, Orlando Saenz, the National Association of Manufacturers and the fascist-led Agricultural Society, Benjamin Matte, among others.

At the time I was on sabbatical from UC Santa Cruz where I had just established a Latin American Studies program. I presented myself as a sympathetic gringa to the leaders who would lay the foundations for the military coup. One thing never left my mind. Orlando Saenz, the head of SOFOFA, explained to me that he was grateful for Allende because now they knew everyone who would have to be killed.

In the course of my interviews I realized that these opposition leaders thought I was CIA and ready to bring more funds to them. But this is not the reason I am haunted. It is the similarities in opposition developments.

The Shortages: If you were poor, you had access to what was called “the popular basket,” cesta popular, that included basic foods, cooking oil, matches and toilet paper. If you were rich, you had all these things from the black market. I was neither, and therefore found life quite hard. Without cooking oil, it was hard to cook, but even harder if you had no matches to light the stove. What was particularly annoying, however, was the lack of toilet paper. I soon concluded that if you want to turn the middle classes against a government, just take away their toilet paper. The owner of El Mercurio, the main conservative newspaper, owned the paper company. (He was also international vice-president of Pepsi Cola.) The UP (Popular Unity Government) discovered tens of thousands of rolls of toilet paper thrown into the Mapuche River. It was, in fact, part of the strategic boycott.

US Economic Blockade: The US economic blockade, for example, prevented any bus parts from arriving in Chile. The shortage of buses made travel in Santiago almost impossible. The country was using volkswagon mini-buses and anything with wheels to transport people. Buses would pass and there was not even a window you could hang onto. People were out the door holding each others’ waists. As they were doing to Cuba, the US did to Chile. No aid, no trade, no imports, no exports.

Street Mobilizations: Then the pots and pans in the upper middle class barrio took to the streets, causing disruptions and general chaos.

President Allende did not respond with repression. In fact, he was convinced that the military in Chile was and would always be a supporter of democracy. He was wrong.

Pinochet was the US front man, preparing for a brutal military takeover. Training of Chilean military in Panama increased, as did US military funding. Training of right-wing trade unionists increased, done by the AFL-CIO’s international arm, the American Institute for Free Labor Development (AIFLD). I know this because I went to AIFLD’s training center and wrote down the names of Chilean students who attended over the two years preceding the coup. They were, for the most part, opposition leaders; some worked as agents turning in names of democratic union leaders so they could be rounded up and killed.

Allende decided to disarm rather than arm the masses, to placate Pinochet. The industrial strips outside of the capital were controlled by the workers and their unions. The workers were asked to disarm to show the world that Chile was on the road to socialism peacefully.

But the most lasting and gut-wrenching lesson I learned was that the ruling class was as class conscious as the working class, but with all the resources of the US behind them. That has been the case more recently in Brazil and Argentina. It is currently the case in Venezuela. The ruling class took revenge. What can the government of Venezuela do to resist? I do not know. What I do know is that an armed and conscious ruling class is a lethal and immensely powerful weapon.

There are many lessons I learned from my Chilean experiences, but the class consciousness of the 1% stood out. I lost many friends and two US co-workers in that coup on September 11, 1973. The book I contributed to, by the way, Los gremios patronales, was published on September 10, 1973. One copy was mailed to me. The rest were burned after September 11th.

Ruth Needleman, professor emerita, Indiana University

On The 50th Anniversary Of Kissinger’s Bloody Paper Trail in Chile

THE SECRET MEMO IN WHICH HE PLOTTED THE MURDER OF CHILEAN DEMOCRACY.

https://www.thenation.com/article/world/kissinger-nixon-pinohet-chile-secret-memo/?fbclid=IwAR2MbynfYjJKcllrcAcA2mRKV2oJoOpfZiSTeRjgyUcr4DlGxyHuq-pv-6A

BY PETER KORNBLUHTWITTER

MAY 15, 2023

As Henry Kissinger reaches 100 years of age on May 27, Chileans are preparing to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the bloody military coup that the former US national security adviser helped orchestrate in September 1973. Kissinger’s controversial career is littered with scandals and crimes against humanity: support for mass murderers and torturers abroad, domestic wiretapping, clandestine wars in Indochina, and, as Greg Grandin reminds us, secretly sabotaging the quest for peace in Vietnam. But his pivotal role in the covert US efforts to undermine democracy in Chile, aiding and abetting the rise of the infamous dictator Augusto Pinochet, will always be the Achilles’ heel of Kissinger’s much-ballyhooed legacy.

GREG GRANDIN

The declassified historical record leaves no doubt that Kissinger was the chief architect of US efforts to destabilize the democratically elected government of Socialist Party leader Salvador Allende. Once Allende was overthrown, Kissinger became the leading enabler of Pinochet’s repressive new regime. “I think we should understand our policy—that however unpleasant they act, this government is better for us than Allende was,” he told his deputies as they reported to him on the human rights atrocities in the weeks following the coup. At a private June 1976 meeting with Pinochet in Santiago, Secretary of State Kissinger offered platitudes rather than pressure: “My evaluation is that you are a victim of all left-wing groups around the world,” he told Pinochet, “and that your greatest sin was that you overthrew a government which was going communist.”

❶ Between Allende’s election on September 4, 1970, and his inauguration two months later, the CIA launched a major covert operation to block his ascendance to the presidency. Ordered by President Nixon and overseen by Kissinger, the operation—code-named FUBELT—led to the assassination of Gen. René Schneider, the pro-constitution commander in chief of the Chilean Army. But the operation failed to foment a military coup.

The day after Allende’s inauguration, Nixon scheduled a meeting of his National Security Council on November 5 to establish what US policy toward Chile would be. But Kissinger requested that the meeting be postponed by a day to give him time to personally present this pivotal memorandum to Nixon and persuade him to reject the State Department’s position that Washington could establish a modus vivendi with an Allende government. Kissinger lobbied the president to adopt an aggressive, if covert, effort to “oppose Allende as strongly as we can.”

❷ In his presentation to the president, Kissinger acknowledged that Allende had been legitimately and democratically elected—“the first Marxist government ever to come to power by free elections”—and would adopt a moderate position toward the United States. In Kissingerian logic, that made Allende even more of a threat. Among the rationales Kissinger presented for destabilizing Allende’s new government was one key factor: “The example of a successful elected Marxist government in Chile would surely have an impact on—and even precedent value for—other parts of the world, especially in Italy. The imitative spread of similar phenomena elsewhere would in turn significantly affect the world balance and our own position in it.” As Kissinger advised the president, “its ‘model’ effect can be insidious.”

❸ Kissinger successfully persuaded the president to approve this clandestine destabilization policy. At the NSC meeting the next day, Kissinger reiterated his arguments for intervention. “Developments in Chile are clearly of major historic importance, and they will have ramifications that go far beyond just the question of US-Chilean relations,” his talking points for the NSC meeting dramatically began. “The question therefore,” Kissinger stated after outlining the purported threats to US interests of a successful Allende government, “is whether there are actions we can take ourselves to intensify Allende’s problems so that at a minimum he may fail or be forced to limit his aims, and at a maximum might create conditions in which collapse or overthrow might be feasible.”

❹ At the NSC meeting the next day, according to a secret summary, Nixon backed Kissinger and parroted his position. “Our main concern in Chile is the prospect that he [Allende] can consolidate himself and the picture presented to the world will be his success,” the president informed his top national security managers.

❺ The objective of Kissinger’s policy of hostile intervention came to fruition on September 11, 1973—Chile’s own 9/11. Kissinger then ushered in a policy of assisting the new military regime, which would become renowned for murder, torture, disappearances, and even international terrorism on the streets of Washington, D.C.

“The Chilean thing is getting consolidated,” Kissinger informed Nixon a few days after the coup, “and of course the newspapers are bleating because a pro-Communist government has been overthrown.” “Isn’t that something,” Nixon mused about what he called “this crap from the Liberals” on the denouement of democracy in Chile. “Isn’t that something.”

Kissinger also lamented the failure of the US press to celebrate their Cold War accomplishment. As he told Nixon, “in the Eisenhower period we would be heroes.”

PETER KORNBLUHTWITTERPeter Kornbluh, a longtime contributor to The Nation on Cuba, is co-author, with William M. LeoGrande, of Back Channel to Cuba: The Hidden History of Negotiations Between Washington and Havana. Kornbluh is also the author of The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability.

On The 50th Anniversary: The CIA and Chile: Anatomy of an Assassination

https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/briefing-book/chile/2020-10-22/cia-chile-anatomy-assassination

Schneider official portrait

Chile Marks 50th Anniversary of Assassination of Chilean Commander-in-Chief, General René Schneider

'60 Minutes' Posts Dramatic Exposé on Henry Kissinger’s Role and Schneider Family Lawsuit

Schneider’s Murder: “a stain on the pages of contemporary history”

Published: Oct 22, 2020

Briefing Book #

728

Edited by Peter Kornbluh and Savannah Bock

For more information, contact:

202-994-7000 or peter.kornbluh [at] gmail.com

Subjects

Covert Action

Human Rights and Genocide

Political Crimes and Abuse of Power

Regions

South America

Events

Chile – Coup d’État, 1973

Project

Chile

Schneider CIA commendation

Schneider cadet

Schneider as a teenage cadet at Chile's Escuela Militar

Schneider CIA self credit

Special report

Washington D.C., October 22, 2020 - On October 23, 1970, one day after armed thugs intercepted and mortally wounded the Chilean army commander-in-chief, General Rene Schneider, as he drove to work in Santiago, CIA Director Richard Helms convened his top aides to review the covert coup operations that had led to the attack. “[I]t was agreed that … a maximum effort has been achieved,” and that “the station has done excellent job of guiding Chileans to point today where a military solution is at least an option for them,” stated a Secret cable of commendation transmitted that day to the CIA station in Chile. “COS [Chief of Station] … and Station [deleted] are commended for accomplishing this under extremely difficult and delicate circumstances.”

At the State Department, officials had no idea that the CIA and the highest levels of the Nixon White House had backed the attack on Schneider—with pressure, weapons, and money—as a pretext for a military coup that would overturn the democratic election of Salvador Allende. They drafted a condolence letter for President Nixon to send. In a memo to National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger, who was secretly supervising the CIA’s coup operations, the State Department recommended that Nixon convey the following message to the President of Chile: “Dear Mr. President: The shocking attempt on the life of General Schneider is a stain on the pages of contemporary history. I would like you to know of my sorrow that this repugnant event has occurred in your country….”

Marking the 50th anniversary of the U.S.-supported attack on General Schneider, the National Security Archive today is posting a collection of previously declassified records to commemorate this “repugnant event.” The Archive has also posted a CBS '60 Minutes' segment, “Schneider vs. Kissinger,” that drew on these documents to report on a “wrongful death” lawsuit filed in September 2001 by the Schneider family against Kissinger for his role in the assassination. The '60 Minutes' broadcast aired on September 9, 2001 and has not been publicly available since then. In preparation for the 50th anniversary, CBS News graciously posted the broadcast as a “60 Minutes Rewind” yesterday.

60min

From the '60 Minutes' Archives: Schneider v. Kissinger

In Chile, the assassination of General Schneider remains the historical equivalent of the assassination of John F. Kennedy: a cruel and shocking political crime that shook the nation. In the United States, the murder of Schneider has become one of the most renowned case studies of CIA efforts to “neutralize” a foreign leader who stood in the way of U.S. objectives.

The CIA’s murderous covert operations to, as CIA officials suggested, “effect the removal of Schneider,” were first revealed in a 1975 Senate report on Alleged Assassination Plots Involving Foreign Leaders. At the time, investigators for the special Senate committee led by Idaho Senator Frank Church were able to review the Top Secret CIA operational cables and memoranda relating to “Operation FUBELT”—the code name for CIA efforts, ordered by Nixon and supervised by Kissinger, to instigate a military coup that would begin with the kidnapping of Schneider. When the Church Committee published its dramatic report, however, almost none of the classified records were made public.

It took 25 more years before President Bill Clinton ordered the release of the CIA records on Operation FUBELT, as part of a massive declassification on Chile in the aftermath of General Augusto Pinochet’s arrest in London for human rights crimes. A close reading of the documentation exposes the false narrative that Kissinger, Richard Helms, and other high ranking officials presented to the Church Committee in their testimonies about their knowledge of, and responsibilities for, an act of political terrorism that led to the shooting of Schneider on October 22, 1970, and his death three days later.

Generalschneider and young family

Schneider and his young family in 1953 traveling to Fort Benning, GA, where he trained as an officer.

General Schneider was targeted for his defense of Chile’s constitutional transfer of power. On May 8, 1970, he gave what the Defense Intelligence Agency described as an “outspoken” interview to Chile’s leading newspaper, El Mercurio, affirming that the Chilean armed forces would not interfere in the September 1970 election—a position that became known as “the Schneider Doctrine.”

As the commander-in-chief of the Chilean army and the highest-ranking military officer in Chile, Schneider’s policy of non-intervention created a major obstacle for CIA efforts to implement President Nixon’s orders to foment a coup that would prevent the recently elected Socialist, Salvador Allende, from being inaugurated. A “key to a coup,” as Chilean newspaper mogul, Agustin Edwards, told CIA Director Helms on September 15, 1970, in Washington, D.C. “would involve neutralizing Schneider” so other Army officers could take action. “General Schneider would have to be neutralized, by displacement if necessary,” U.S. Ambassador Edward Korry pointed out in a September 21, 1970, cable. “Anything we or the Station can do to effect the removal of Schneider?,” the CIA directors of Operation FUBELT queried their agents in Santiago on October 13.

THE SPONSORS

Kidnapping Schneider was the answer. By mid-October, the Defense attaché, Col. Paul Wimert, and CIA operatives known as “false flaggers”—agents flown in from abroad using false identities who were referred to as “sponsors” in the cable traffic—had held multiple meetings with Chilean military officers to discuss this operation. A coup plot beginning with the kidnapping of Schneider would accomplish multiple goals: remove the most powerful opponent of a military golpe; replace him with a military officer sympathetic to a coup; blame the kidnapping on Allende supporters; and create what the CIA referred to as “a coup climate” of upheaval to justify a military takeover.

Initially, the CIA focused on retired General Roberto Viaux as the officer most willing to move against Schneider. In secret meetings with the “false flaggers,” Viaux demanded an air-drop of armaments as well as insurance policies for his men. His CIA “sponsors” promised $250,000 to “keep Viaux movement financially lubricated,” while the CIA tried to coordinate his activities with other coup plotters. Active duty coup plotters were needed because Viaux commanded no troops; he was “a general without an army” who had the capacity to precipitate a coup—but not to successfully implement one.

On October 15, the CIA’s top official in charge of covert operations, Thomas Karamessines, met with Henry Kissinger and his military assistant, Alexander Haig, to update them on the status of coup plotting in Chile. They agreed that a failed coup would have “unfortunate repercussions, in Chile and internationally,” and “the Agency must get a message to Viaux warning him against any precipitate action” that would undermine chances for a successful coup later. According to the meeting minutes, Kissinger instructed the Agency to “continue keeping the pressure on every Allende weak spot in sight….”

The next day, CIA headquarters transmitted the conclusions of the Kissinger meeting “which are to be your operational guide,” to the Santiago station. “It is firm and continuing policy that Allende be overthrown by a coup,” the cable stated, preferably before October 24, when the Chilean Congress was due to ratify Allende’s electoral victory. “We are to continue to generate maximum pressure toward this end utilizing every appropriate resource.” The cable instructed the station chief, Henry Hecksher, to get a message to Viaux to “discourage him from acting alone,” and “encourage him to join forces with other coup planners so that they may act in concert either before or after 24 October.”

That message was delivered, and Viaux did as directed. He met with a pro-coup brigadier general, Camilo Valenzuela, and they coordinated a plan to abduct Schneider on October 19th, as he left a military “stag party” as the trigger for a coup. According to the plan, Schneider would be secretly flown to Argentina; the military would announce that he had “disappeared,” blaming Allende supporters who would then be arrested; President Eduardo Frei would be forced into exile, Congress dissolved, and a new military junta installed in power.

THE ASSASSINATION

The CIA was not only aware of this plan, they credited themselves for its development. “In recent weeks Station false flag officers have made a vigorous effort to contact, advise, and influence key members of the military in an attempt to rally support for a coup,” stated a Top Secret October 20, 1970, memo on the progress of “Track II,” as the coup plotting was designated. “Valenzuela's announcement that the military is now prepared to move may be an indication of the effectiveness of this effort.”

Moreover, the Agency actively supported it. Using Col. Wimert as their primary interlocutor with Valenzuela and his top deputies, CIA operatives arranged to furnish them with untraceable grease guns, tear gas grenades, ammunition, and $50,000 in cash to finance the kidnapping operation. When the first attempt to kidnap Schneider on October 19 failed, as well as a second attempt the next day, the co-directors of the FUBELT task force, David Atlee Phillips and William Broe, instructed the station chief to “assure Valenzuela and others with whom he has been in contact that USG support for anti-Allende action continues.”

On the morning of October 22, 1970, Schneider’s chauffeured car was struck and stopped by a jeep as he drove to military headquarters. A hit team surrounded the car; as one member smashed the back window with sledgehammer, Schneider reached for his pistol and was shot at close range. He died of his wounds three days later.

Although CIA officials had discussed the potential for the abduction to turn violent, assassinating Schneider had not been part of the plan. Nevertheless, the CIA’s own post mortems on the operation showed no remorse. To the contrary, Agency officials firmly believed that the “die has been cast” for a coup to move forward. In his first report to Langley, the station chief, Henry Hecksher, cabled that “all we can say is that attempt against Schneider is affording armed forces one last opportunity to prevent Allende’s election….” At Langley headquarters, Richard Helms and his deputies congratulated the station on their “excellent job.” CIA analysts on the FUBELT task force predicted that the coup would now take place since the assassins would fear being prosecuted after Allende assumed office. The plotters would either “try and force Frei to resign or they can attempt to assassinate Allende,” a special report on the “Machine gun Assault on General Schneider” asserted. “Hence, they have no alternative but to move ahead,” another task force report suggested. “The state of emergency and the establishment of martial law have significantly improved the plotters position: a coup climate now prevails in Chile.”

The opposite was true. Repulsed by an act of political terrorism on the streets of Santiago, the Chilean public, the political elite and even General Carlos Prats who replaced Schneider as commander-in-chief, rallied to protect the constitutional processes which Schneider had defended. “The assassination of Army Commander in Chief Schneider has practically ended the possibility of any military action against Allende. It apparently has unified the armed forces behind acceptance and support of him as constitutional president in a way that few other developments could have done,” the CIA’s own analytical division, the Directorate of Intelligence, reported in the aftermath of Schneider’s death. On October 24, Allende was overwhelmingly ratified by the Chilean Congress. On November 3, he was inaugurated as the first freely elected Socialist leader in the world.

A COVER UP AND THE PURSUIT OF JUSTICE

In the aftermath of the assassination the CIA went to great lengths to cover up all evidence of its involvement with General Valenzuela, and to pay off General Viaux and his accomplices to stay silent. Colonel Wimert retrieved the weapons that had been sent—they were disposed of in the ocean—and the $50,000 that had been passed to Valenzuela. Although CIA officials testified before the Church Committee that they had no further contact with Viaux and his team after October 18, 1970, in fact they had multiple contacts as his representatives sought, in the ensuing months, $250,000 dollars to support the families of the men involved in the plot. Eventually, the CIA paid out $35,000 in hush money to representatives of the assassination team, according to a later CIA report submitted to the House Intelligence Committee, “in an effort to keep previous contact secret, maintain the good will of the group and for humanitarian reasons.”

For his part, Kissinger testified before the Church Committee that he had “turned off” coup plotting during the meeting with the CIA on October 15, 1970, and had never been informed that the plot involved kidnapping General Schneider. When the CIA records that appeared to contradict Kissinger’s dubious narrative were declassified during the Clinton administration, the National Security Archive’s Chile analyst Peter Kornbluh provided them to the Schneider family; they then used the documentation as evidence of complicity in a “wrongful death” civil lawsuit against Kissinger. "Recently declassified U.S. government documents and Congressional reports have provided Plaintiffs with the information, necessary to bring this action,” their legal petition stated. “The documents show that the knowing practical assistance and encouragement provided by the United States and the official and ultra vires acts of Henry Kissinger resulted in General Schneider's summary execution, torture, cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment, arbitrary detention, assault and battery, negligence, intentional infliction of emotional distress, and wrongful death."

According to the lawsuit, "the government documents show that, beginning in or about 1970, Defendants directed, controlled, committed, conspired to commit, assisted, encouraged, acted jointly to commit, aided and abetted, and/or were intimately aware of overt as well as covert activities to prevent Dr. Salvador Allende's accession to the Chilean Presidency. These activities included the organization and instigation of a military coup d'etat in Chile that required the removal of General Rene Schneider, father of Plaintiffs Rene and Raul Schneider.”

Lawyers for the Schneider family filed the suit in District Court in Washington,D.C., on September 10, 2001. Eventually, the courts dismissed the case because Kissinger’s official acts as national security advisor to the president were protected from legal liability.

By Ruth Needleman

https://portside.org/2017-07-03/memories-chile

As I watch current events in Venezuela, I am haunted by memories of Chile. I lived in Chile from July 1972 until February 1973, while socialist Salvador Allende was president.

I left Chile months before the fascist coup, although I had planned to return. That door closed.

Nonetheless I was there for the banging of pots and pans, the incredible shortages, the right-wing mobilizations, and in particular, the entrepreneurial strike of October 1972. Maduro is not Allende, and Venezuela is not Chile. Forty-four years and radically changing conditions separate them. Yet we are living a period of right-wing backlash and government takeovers, not unlike the sixties and seventies in Latin America.

I am haunted by memories because of the similarities in the right-wing opposition tactics. I came to know them intimately, in large part because after the October 1972 strike. I researched the right-wing opposition to Allende as part of a volunteer job I was doing at Quimantu, the National Publishing House. After I completed a chronology for a book Quimantu was doing, I began to interview the right-wing leaders of the opposition.

I started with the truck owner Vilarin but got introduced up the line to the president of SOFOFA, Orlando Saenz, the National Association of Manufacturers and the fascist-led Agricultural Society, Benjamin Matte, among others.

At the time I was on sabbatical from UC Santa Cruz where I had just established a Latin American Studies program. I presented myself as a sympathetic gringa to the leaders who would lay the foundations for the military coup. One thing never left my mind. Orlando Saenz, the head of SOFOFA, explained to me that he was grateful for Allende because now they knew everyone who would have to be killed.

In the course of my interviews I realized that these opposition leaders thought I was CIA and ready to bring more funds to them. But this is not the reason I am haunted. It is the similarities in opposition developments.

The Shortages: If you were poor, you had access to what was called “the popular basket,” cesta popular, that included basic foods, cooking oil, matches and toilet paper. If you were rich, you had all these things from the black market. I was neither, and therefore found life quite hard. Without cooking oil, it was hard to cook, but even harder if you had no matches to light the stove. What was particularly annoying, however, was the lack of toilet paper. I soon concluded that if you want to turn the middle classes against a government, just take away their toilet paper. The owner of El Mercurio, the main conservative newspaper, owned the paper company. (He was also international vice-president of Pepsi Cola.) The UP (Popular Unity Government) discovered tens of thousands of rolls of toilet paper thrown into the Mapuche River. It was, in fact, part of the strategic boycott.

US Economic Blockade: The US economic blockade, for example, prevented any bus parts from arriving in Chile. The shortage of buses made travel in Santiago almost impossible. The country was using volkswagon mini-buses and anything with wheels to transport people. Buses would pass and there was not even a window you could hang onto. People were out the door holding each others’ waists. As they were doing to Cuba, the US did to Chile. No aid, no trade, no imports, no exports.

Street Mobilizations: Then the pots and pans in the upper middle class barrio took to the streets, causing disruptions and general chaos.

President Allende did not respond with repression. In fact, he was convinced that the military in Chile was and would always be a supporter of democracy. He was wrong.

Pinochet was the US front man, preparing for a brutal military takeover. Training of Chilean military in Panama increased, as did US military funding. Training of right-wing trade unionists increased, done by the AFL-CIO’s international arm, the American Institute for Free Labor Development (AIFLD). I know this because I went to AIFLD’s training center and wrote down the names of Chilean students who attended over the two years preceding the coup. They were, for the most part, opposition leaders; some worked as agents turning in names of democratic union leaders so they could be rounded up and killed.

Allende decided to disarm rather than arm the masses, to placate Pinochet. The industrial strips outside of the capital were controlled by the workers and their unions. The workers were asked to disarm to show the world that Chile was on the road to socialism peacefully.

But the most lasting and gut-wrenching lesson I learned was that the ruling class was as class conscious as the working class, but with all the resources of the US behind them. That has been the case more recently in Brazil and Argentina. It is currently the case in Venezuela. The ruling class took revenge. What can the government of Venezuela do to resist? I do not know. What I do know is that an armed and conscious ruling class is a lethal and immensely powerful weapon.

There are many lessons I learned from my Chilean experiences, but the class consciousness of the 1% stood out. I lost many friends and two US co-workers in that coup on September 11, 1973. The book I contributed to, by the way, Los gremios patronales, was published on September 10, 1973. One copy was mailed to me. The rest were burned after September 11th.

Ruth Needleman, professor emerita, Indiana University

Memories of Chile On The 49th Anniversary Of The US AFL-CIO Supported Coup

By Ruth Needleman

https://portside.org/2017-07-03/memories-chile

As I watch current events in Venezuela, I am haunted by memories of Chile. I lived in Chile from July 1972 until February 1973, while socialist Salvador Allende was president.

I left Chile months before the fascist coup, although I had planned to return. That door closed.

Nonetheless I was there for the banging of pots and pans, the incredible shortages, the right-wing mobilizations, and in particular, the entrepreneurial strike of October 1972. Maduro is not Allende, and Venezuela is not Chile. Forty-four years and radically changing conditions separate them. Yet we are living a period of right-wing backlash and government takeovers, not unlike the sixties and seventies in Latin America.

I am haunted by memories because of the similarities in the right-wing opposition tactics. I came to know them intimately, in large part because after the October 1972 strike. I researched the right-wing opposition to Allende as part of a volunteer job I was doing at Quimantu, the National Publishing House. After I completed a chronology for a book Quimantu was doing, I began to interview the right-wing leaders of the opposition.

I started with the truck owner Vilarin but got introduced up the line to the president of SOFOFA, Orlando Saenz, the National Association of Manufacturers and the fascist-led Agricultural Society, Benjamin Matte, among others.

At the time I was on sabbatical from UC Santa Cruz where I had just established a Latin American Studies program. I presented myself as a sympathetic gringa to the leaders who would lay the foundations for the military coup. One thing never left my mind. Orlando Saenz, the head of SOFOFA, explained to me that he was grateful for Allende because now they knew everyone who would have to be killed.

In the course of my interviews I realized that these opposition leaders thought I was CIA and ready to bring more funds to them. But this is not the reason I am haunted. It is the similarities in opposition developments.

The Shortages: If you were poor, you had access to what was called “the popular basket,” cesta popular, that included basic foods, cooking oil, matches and toilet paper. If you were rich, you had all these things from the black market. I was neither, and therefore found life quite hard. Without cooking oil, it was hard to cook, but even harder if you had no matches to light the stove. What was particularly annoying, however, was the lack of toilet paper. I soon concluded that if you want to turn the middle classes against a government, just take away their toilet paper. The owner of El Mercurio, the main conservative newspaper, owned the paper company. (He was also international vice-president of Pepsi Cola.) The UP (Popular Unity Government) discovered tens of thousands of rolls of toilet paper thrown into the Mapuche River. It was, in fact, part of the strategic boycott.

US Economic Blockade: The US economic blockade, for example, prevented any bus parts from arriving in Chile. The shortage of buses made travel in Santiago almost impossible. The country was using volkswagon mini-buses and anything with wheels to transport people. Buses would pass and there was not even a window you could hang onto. People were out the door holding each others’ waists. As they were doing to Cuba, the US did to Chile. No aid, no trade, no imports, no exports.

Street Mobilizations: Then the pots and pans in the upper middle class barrio took to the streets, causing disruptions and general chaos.

President Allende did not respond with repression. In fact, he was convinced that the military in Chile was and would always be a supporter of democracy. He was wrong.

Pinochet was the US front man, preparing for a brutal military takeover. Training of Chilean military in Panama increased, as did US military funding. Training of right-wing trade unionists increased, done by the AFL-CIO’s international arm, the American Institute for Free Labor Development (AIFLD). I know this because I went to AIFLD’s training center and wrote down the names of Chilean students who attended over the two years preceding the coup. They were, for the most part, opposition leaders; some worked as agents turning in names of democratic union leaders so they could be rounded up and killed.

Allende decided to disarm rather than arm the masses, to placate Pinochet. The industrial strips outside of the capital were controlled by the workers and their unions. The workers were asked to disarm to show the world that Chile was on the road to socialism peacefully.

But the most lasting and gut-wrenching lesson I learned was that the ruling class was as class conscious as the working class, but with all the resources of the US behind them. That has been the case more recently in Brazil and Argentina. It is currently the case in Venezuela. The ruling class took revenge. What can the government of Venezuela do to resist? I do not know. What I do know is that an armed and conscious ruling class is a lethal and immensely powerful weapon.

There are many lessons I learned from my Chilean experiences, but the class consciousness of the 1% stood out. I lost many friends and two US co-workers in that coup on September 11, 1973. The book I contributed to, by the way, Los gremios patronales, was published on September 10, 1973. One copy was mailed to me. The rest were burned after September 11th.

Ruth Needleman, professor emerita, Indiana University

On The 50th Anniversary Of Kissinger’s Bloody Paper Trail in Chile

THE SECRET MEMO IN WHICH HE PLOTTED THE MURDER OF CHILEAN DEMOCRACY.

https://www.thenation.com/article/world/kissinger-nixon-pinohet-chile-secret-memo/?fbclid=IwAR2MbynfYjJKcllrcAcA2mRKV2oJoOpfZiSTeRjgyUcr4DlGxyHuq-pv-6A

BY PETER KORNBLUHTWITTER

MAY 15, 2023

As Henry Kissinger reaches 100 years of age on May 27, Chileans are preparing to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the bloody military coup that the former US national security adviser helped orchestrate in September 1973. Kissinger’s controversial career is littered with scandals and crimes against humanity: support for mass murderers and torturers abroad, domestic wiretapping, clandestine wars in Indochina, and, as Greg Grandin reminds us, secretly sabotaging the quest for peace in Vietnam. But his pivotal role in the covert US efforts to undermine democracy in Chile, aiding and abetting the rise of the infamous dictator Augusto Pinochet, will always be the Achilles’ heel of Kissinger’s much-ballyhooed legacy.

GREG GRANDIN

The declassified historical record leaves no doubt that Kissinger was the chief architect of US efforts to destabilize the democratically elected government of Socialist Party leader Salvador Allende. Once Allende was overthrown, Kissinger became the leading enabler of Pinochet’s repressive new regime. “I think we should understand our policy—that however unpleasant they act, this government is better for us than Allende was,” he told his deputies as they reported to him on the human rights atrocities in the weeks following the coup. At a private June 1976 meeting with Pinochet in Santiago, Secretary of State Kissinger offered platitudes rather than pressure: “My evaluation is that you are a victim of all left-wing groups around the world,” he told Pinochet, “and that your greatest sin was that you overthrew a government which was going communist.”

❶ Between Allende’s election on September 4, 1970, and his inauguration two months later, the CIA launched a major covert operation to block his ascendance to the presidency. Ordered by President Nixon and overseen by Kissinger, the operation—code-named FUBELT—led to the assassination of Gen. René Schneider, the pro-constitution commander in chief of the Chilean Army. But the operation failed to foment a military coup.

The day after Allende’s inauguration, Nixon scheduled a meeting of his National Security Council on November 5 to establish what US policy toward Chile would be. But Kissinger requested that the meeting be postponed by a day to give him time to personally present this pivotal memorandum to Nixon and persuade him to reject the State Department’s position that Washington could establish a modus vivendi with an Allende government. Kissinger lobbied the president to adopt an aggressive, if covert, effort to “oppose Allende as strongly as we can.”

❷ In his presentation to the president, Kissinger acknowledged that Allende had been legitimately and democratically elected—“the first Marxist government ever to come to power by free elections”—and would adopt a moderate position toward the United States. In Kissingerian logic, that made Allende even more of a threat. Among the rationales Kissinger presented for destabilizing Allende’s new government was one key factor: “The example of a successful elected Marxist government in Chile would surely have an impact on—and even precedent value for—other parts of the world, especially in Italy. The imitative spread of similar phenomena elsewhere would in turn significantly affect the world balance and our own position in it.” As Kissinger advised the president, “its ‘model’ effect can be insidious.”

❸ Kissinger successfully persuaded the president to approve this clandestine destabilization policy. At the NSC meeting the next day, Kissinger reiterated his arguments for intervention. “Developments in Chile are clearly of major historic importance, and they will have ramifications that go far beyond just the question of US-Chilean relations,” his talking points for the NSC meeting dramatically began. “The question therefore,” Kissinger stated after outlining the purported threats to US interests of a successful Allende government, “is whether there are actions we can take ourselves to intensify Allende’s problems so that at a minimum he may fail or be forced to limit his aims, and at a maximum might create conditions in which collapse or overthrow might be feasible.”

❹ At the NSC meeting the next day, according to a secret summary, Nixon backed Kissinger and parroted his position. “Our main concern in Chile is the prospect that he [Allende] can consolidate himself and the picture presented to the world will be his success,” the president informed his top national security managers.

❺ The objective of Kissinger’s policy of hostile intervention came to fruition on September 11, 1973—Chile’s own 9/11. Kissinger then ushered in a policy of assisting the new military regime, which would become renowned for murder, torture, disappearances, and even international terrorism on the streets of Washington, D.C.

“The Chilean thing is getting consolidated,” Kissinger informed Nixon a few days after the coup, “and of course the newspapers are bleating because a pro-Communist government has been overthrown.” “Isn’t that something,” Nixon mused about what he called “this crap from the Liberals” on the denouement of democracy in Chile. “Isn’t that something.”

Kissinger also lamented the failure of the US press to celebrate their Cold War accomplishment. As he told Nixon, “in the Eisenhower period we would be heroes.”

PETER KORNBLUHTWITTERPeter Kornbluh, a longtime contributor to The Nation on Cuba, is co-author, with William M. LeoGrande, of Back Channel to Cuba: The Hidden History of Negotiations Between Washington and Havana. Kornbluh is also the author of The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability.

On The 50th Anniversary: The CIA and Chile: Anatomy of an Assassination

https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/briefing-book/chile/2020-10-22/cia-chile-anatomy-assassination

Schneider official portrait

Chile Marks 50th Anniversary of Assassination of Chilean Commander-in-Chief, General René Schneider

'60 Minutes' Posts Dramatic Exposé on Henry Kissinger’s Role and Schneider Family Lawsuit

Schneider’s Murder: “a stain on the pages of contemporary history”

Published: Oct 22, 2020

Briefing Book #

728

Edited by Peter Kornbluh and Savannah Bock

For more information, contact:

202-994-7000 or peter.kornbluh [at] gmail.com

Subjects

Covert Action

Human Rights and Genocide

Political Crimes and Abuse of Power

Regions

South America

Events

Chile – Coup d’État, 1973

Project

Chile

Schneider CIA commendation

Schneider cadet

Schneider as a teenage cadet at Chile's Escuela Militar

Schneider CIA self credit

Special report

Washington D.C., October 22, 2020 - On October 23, 1970, one day after armed thugs intercepted and mortally wounded the Chilean army commander-in-chief, General Rene Schneider, as he drove to work in Santiago, CIA Director Richard Helms convened his top aides to review the covert coup operations that had led to the attack. “[I]t was agreed that … a maximum effort has been achieved,” and that “the station has done excellent job of guiding Chileans to point today where a military solution is at least an option for them,” stated a Secret cable of commendation transmitted that day to the CIA station in Chile. “COS [Chief of Station] … and Station [deleted] are commended for accomplishing this under extremely difficult and delicate circumstances.”

At the State Department, officials had no idea that the CIA and the highest levels of the Nixon White House had backed the attack on Schneider—with pressure, weapons, and money—as a pretext for a military coup that would overturn the democratic election of Salvador Allende. They drafted a condolence letter for President Nixon to send. In a memo to National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger, who was secretly supervising the CIA’s coup operations, the State Department recommended that Nixon convey the following message to the President of Chile: “Dear Mr. President: The shocking attempt on the life of General Schneider is a stain on the pages of contemporary history. I would like you to know of my sorrow that this repugnant event has occurred in your country….”

Marking the 50th anniversary of the U.S.-supported attack on General Schneider, the National Security Archive today is posting a collection of previously declassified records to commemorate this “repugnant event.” The Archive has also posted a CBS '60 Minutes' segment, “Schneider vs. Kissinger,” that drew on these documents to report on a “wrongful death” lawsuit filed in September 2001 by the Schneider family against Kissinger for his role in the assassination. The '60 Minutes' broadcast aired on September 9, 2001 and has not been publicly available since then. In preparation for the 50th anniversary, CBS News graciously posted the broadcast as a “60 Minutes Rewind” yesterday.

60min

From the '60 Minutes' Archives: Schneider v. Kissinger

In Chile, the assassination of General Schneider remains the historical equivalent of the assassination of John F. Kennedy: a cruel and shocking political crime that shook the nation. In the United States, the murder of Schneider has become one of the most renowned case studies of CIA efforts to “neutralize” a foreign leader who stood in the way of U.S. objectives.

The CIA’s murderous covert operations to, as CIA officials suggested, “effect the removal of Schneider,” were first revealed in a 1975 Senate report on Alleged Assassination Plots Involving Foreign Leaders. At the time, investigators for the special Senate committee led by Idaho Senator Frank Church were able to review the Top Secret CIA operational cables and memoranda relating to “Operation FUBELT”—the code name for CIA efforts, ordered by Nixon and supervised by Kissinger, to instigate a military coup that would begin with the kidnapping of Schneider. When the Church Committee published its dramatic report, however, almost none of the classified records were made public.

It took 25 more years before President Bill Clinton ordered the release of the CIA records on Operation FUBELT, as part of a massive declassification on Chile in the aftermath of General Augusto Pinochet’s arrest in London for human rights crimes. A close reading of the documentation exposes the false narrative that Kissinger, Richard Helms, and other high ranking officials presented to the Church Committee in their testimonies about their knowledge of, and responsibilities for, an act of political terrorism that led to the shooting of Schneider on October 22, 1970, and his death three days later.

Generalschneider and young family

Schneider and his young family in 1953 traveling to Fort Benning, GA, where he trained as an officer.

General Schneider was targeted for his defense of Chile’s constitutional transfer of power. On May 8, 1970, he gave what the Defense Intelligence Agency described as an “outspoken” interview to Chile’s leading newspaper, El Mercurio, affirming that the Chilean armed forces would not interfere in the September 1970 election—a position that became known as “the Schneider Doctrine.”

As the commander-in-chief of the Chilean army and the highest-ranking military officer in Chile, Schneider’s policy of non-intervention created a major obstacle for CIA efforts to implement President Nixon’s orders to foment a coup that would prevent the recently elected Socialist, Salvador Allende, from being inaugurated. A “key to a coup,” as Chilean newspaper mogul, Agustin Edwards, told CIA Director Helms on September 15, 1970, in Washington, D.C. “would involve neutralizing Schneider” so other Army officers could take action. “General Schneider would have to be neutralized, by displacement if necessary,” U.S. Ambassador Edward Korry pointed out in a September 21, 1970, cable. “Anything we or the Station can do to effect the removal of Schneider?,” the CIA directors of Operation FUBELT queried their agents in Santiago on October 13.

THE SPONSORS

Kidnapping Schneider was the answer. By mid-October, the Defense attaché, Col. Paul Wimert, and CIA operatives known as “false flaggers”—agents flown in from abroad using false identities who were referred to as “sponsors” in the cable traffic—had held multiple meetings with Chilean military officers to discuss this operation. A coup plot beginning with the kidnapping of Schneider would accomplish multiple goals: remove the most powerful opponent of a military golpe; replace him with a military officer sympathetic to a coup; blame the kidnapping on Allende supporters; and create what the CIA referred to as “a coup climate” of upheaval to justify a military takeover.

Initially, the CIA focused on retired General Roberto Viaux as the officer most willing to move against Schneider. In secret meetings with the “false flaggers,” Viaux demanded an air-drop of armaments as well as insurance policies for his men. His CIA “sponsors” promised $250,000 to “keep Viaux movement financially lubricated,” while the CIA tried to coordinate his activities with other coup plotters. Active duty coup plotters were needed because Viaux commanded no troops; he was “a general without an army” who had the capacity to precipitate a coup—but not to successfully implement one.

On October 15, the CIA’s top official in charge of covert operations, Thomas Karamessines, met with Henry Kissinger and his military assistant, Alexander Haig, to update them on the status of coup plotting in Chile. They agreed that a failed coup would have “unfortunate repercussions, in Chile and internationally,” and “the Agency must get a message to Viaux warning him against any precipitate action” that would undermine chances for a successful coup later. According to the meeting minutes, Kissinger instructed the Agency to “continue keeping the pressure on every Allende weak spot in sight….”

The next day, CIA headquarters transmitted the conclusions of the Kissinger meeting “which are to be your operational guide,” to the Santiago station. “It is firm and continuing policy that Allende be overthrown by a coup,” the cable stated, preferably before October 24, when the Chilean Congress was due to ratify Allende’s electoral victory. “We are to continue to generate maximum pressure toward this end utilizing every appropriate resource.” The cable instructed the station chief, Henry Hecksher, to get a message to Viaux to “discourage him from acting alone,” and “encourage him to join forces with other coup planners so that they may act in concert either before or after 24 October.”

That message was delivered, and Viaux did as directed. He met with a pro-coup brigadier general, Camilo Valenzuela, and they coordinated a plan to abduct Schneider on October 19th, as he left a military “stag party” as the trigger for a coup. According to the plan, Schneider would be secretly flown to Argentina; the military would announce that he had “disappeared,” blaming Allende supporters who would then be arrested; President Eduardo Frei would be forced into exile, Congress dissolved, and a new military junta installed in power.

THE ASSASSINATION

The CIA was not only aware of this plan, they credited themselves for its development. “In recent weeks Station false flag officers have made a vigorous effort to contact, advise, and influence key members of the military in an attempt to rally support for a coup,” stated a Top Secret October 20, 1970, memo on the progress of “Track II,” as the coup plotting was designated. “Valenzuela's announcement that the military is now prepared to move may be an indication of the effectiveness of this effort.”

Moreover, the Agency actively supported it. Using Col. Wimert as their primary interlocutor with Valenzuela and his top deputies, CIA operatives arranged to furnish them with untraceable grease guns, tear gas grenades, ammunition, and $50,000 in cash to finance the kidnapping operation. When the first attempt to kidnap Schneider on October 19 failed, as well as a second attempt the next day, the co-directors of the FUBELT task force, David Atlee Phillips and William Broe, instructed the station chief to “assure Valenzuela and others with whom he has been in contact that USG support for anti-Allende action continues.”

On the morning of October 22, 1970, Schneider’s chauffeured car was struck and stopped by a jeep as he drove to military headquarters. A hit team surrounded the car; as one member smashed the back window with sledgehammer, Schneider reached for his pistol and was shot at close range. He died of his wounds three days later.

Although CIA officials had discussed the potential for the abduction to turn violent, assassinating Schneider had not been part of the plan. Nevertheless, the CIA’s own post mortems on the operation showed no remorse. To the contrary, Agency officials firmly believed that the “die has been cast” for a coup to move forward. In his first report to Langley, the station chief, Henry Hecksher, cabled that “all we can say is that attempt against Schneider is affording armed forces one last opportunity to prevent Allende’s election….” At Langley headquarters, Richard Helms and his deputies congratulated the station on their “excellent job.” CIA analysts on the FUBELT task force predicted that the coup would now take place since the assassins would fear being prosecuted after Allende assumed office. The plotters would either “try and force Frei to resign or they can attempt to assassinate Allende,” a special report on the “Machine gun Assault on General Schneider” asserted. “Hence, they have no alternative but to move ahead,” another task force report suggested. “The state of emergency and the establishment of martial law have significantly improved the plotters position: a coup climate now prevails in Chile.”

The opposite was true. Repulsed by an act of political terrorism on the streets of Santiago, the Chilean public, the political elite and even General Carlos Prats who replaced Schneider as commander-in-chief, rallied to protect the constitutional processes which Schneider had defended. “The assassination of Army Commander in Chief Schneider has practically ended the possibility of any military action against Allende. It apparently has unified the armed forces behind acceptance and support of him as constitutional president in a way that few other developments could have done,” the CIA’s own analytical division, the Directorate of Intelligence, reported in the aftermath of Schneider’s death. On October 24, Allende was overwhelmingly ratified by the Chilean Congress. On November 3, he was inaugurated as the first freely elected Socialist leader in the world.

A COVER UP AND THE PURSUIT OF JUSTICE

In the aftermath of the assassination the CIA went to great lengths to cover up all evidence of its involvement with General Valenzuela, and to pay off General Viaux and his accomplices to stay silent. Colonel Wimert retrieved the weapons that had been sent—they were disposed of in the ocean—and the $50,000 that had been passed to Valenzuela. Although CIA officials testified before the Church Committee that they had no further contact with Viaux and his team after October 18, 1970, in fact they had multiple contacts as his representatives sought, in the ensuing months, $250,000 dollars to support the families of the men involved in the plot. Eventually, the CIA paid out $35,000 in hush money to representatives of the assassination team, according to a later CIA report submitted to the House Intelligence Committee, “in an effort to keep previous contact secret, maintain the good will of the group and for humanitarian reasons.”

For his part, Kissinger testified before the Church Committee that he had “turned off” coup plotting during the meeting with the CIA on October 15, 1970, and had never been informed that the plot involved kidnapping General Schneider. When the CIA records that appeared to contradict Kissinger’s dubious narrative were declassified during the Clinton administration, the National Security Archive’s Chile analyst Peter Kornbluh provided them to the Schneider family; they then used the documentation as evidence of complicity in a “wrongful death” civil lawsuit against Kissinger. "Recently declassified U.S. government documents and Congressional reports have provided Plaintiffs with the information, necessary to bring this action,” their legal petition stated. “The documents show that the knowing practical assistance and encouragement provided by the United States and the official and ultra vires acts of Henry Kissinger resulted in General Schneider's summary execution, torture, cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment, arbitrary detention, assault and battery, negligence, intentional infliction of emotional distress, and wrongful death."

According to the lawsuit, "the government documents show that, beginning in or about 1970, Defendants directed, controlled, committed, conspired to commit, assisted, encouraged, acted jointly to commit, aided and abetted, and/or were intimately aware of overt as well as covert activities to prevent Dr. Salvador Allende's accession to the Chilean Presidency. These activities included the organization and instigation of a military coup d'etat in Chile that required the removal of General Rene Schneider, father of Plaintiffs Rene and Raul Schneider.”

Lawyers for the Schneider family filed the suit in District Court in Washington,D.C., on September 10, 2001. Eventually, the courts dismissed the case because Kissinger’s official acts as national security advisor to the president were protected from legal liability.

For more information:

https://aflcio-int.education/

We are 100% volunteer and depend on your participation to sustain our efforts!

Get Involved

If you'd like to help with maintaining or developing the website, contact us.

Publish

Publish your stories and upcoming events on Indybay.

Topics

More

Search Indybay's Archives

Advanced Search

►

▼

IMC Network