From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

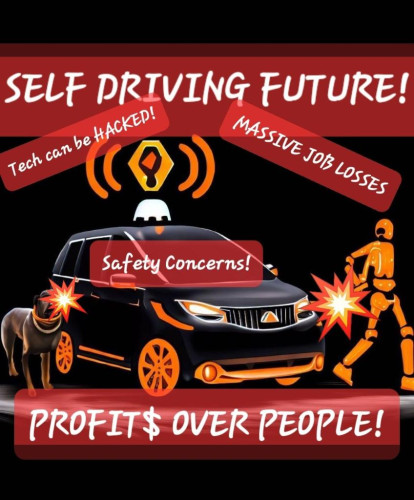

Stop Robo Madness Now! SF Taxi & Uber Drivers Protest Dangers Of AI Cars & The Tech Barons

A rally was held at the California Public Utilities commission in San Francisco against approving having hundreds of robo taxis in San Francisco. This will put thousands of workers out of work and also create deadly health and safety dangers.

A rally was held in San Francisco to demand the halt of hundreds of robo taxies in San Francisco. The California Public Utilities Commission will be voting on this on July 13, 2023. Speakers at the PUC talked about the dangers of these cars and also that they will put thousands of taxi drivers and UBER/Lyft drivers out of worker with no studies by the CPUC.

The Taxi Workers Workers Alliance speakers talked about the devastating effect on workers and medallion drivers and disabled and elderly for shopping who need a human being.

Additional Media:

Stop The Robos Madness NOW! SF Taxi / UBER Drivers Protest Dangers Of AI Cars & Billionaires Control

https://youtu.be/EeSkURmU9Zw

WorkWeek 6-28-23 SF AI Ground Zero & Robo Cars Threaten Workers & Safety With Edward Escobar & Mark Gruber

https://soundcloud.com/workweek-radio/ww-6-28-23-sf-ai-ground-zero-robo-cars-theaten-workers-safety-with-edward-escobar-mark-gruber

Production of WorkWeek

http://www.labormedia.net

The Taxi Workers Workers Alliance speakers talked about the devastating effect on workers and medallion drivers and disabled and elderly for shopping who need a human being.

Additional Media:

Stop The Robos Madness NOW! SF Taxi / UBER Drivers Protest Dangers Of AI Cars & Billionaires Control

https://youtu.be/EeSkURmU9Zw

WorkWeek 6-28-23 SF AI Ground Zero & Robo Cars Threaten Workers & Safety With Edward Escobar & Mark Gruber

https://soundcloud.com/workweek-radio/ww-6-28-23-sf-ai-ground-zero-robo-cars-theaten-workers-safety-with-edward-escobar-mark-gruber

Production of WorkWeek

http://www.labormedia.net

For more information:

https://youtu.be/EeSkURmU9Zw

Add Your Comments

Comments

(Hide Comments)

SF has exploited, failed, and bankrupted its taxi drivers

Mayors Lee and Newsom sold pricey medallions to make money -- then let Uber and Lyft make those investments worthless. The drivers deserve help.

https://48hills.org/.../sf-has-exploited-failed-and.../

By MARCELO FONSECA

APRIL 2, 2021

In 2019, in a series of Pulitzer Prize-winning investigations, The New York Times exposed how government officials stood by as a generation of cab drivers was exploited, victimized by predatory lending, trapped with unpayable loans, and driven to poverty and despair:

New York City in particular failed the taxi industry. Two former mayors, Rudolph W. Giuliani and Michael R. Bloomberg, placed political allies inside the Taxi and Limousine Commission and directed it to sell medallions to help them balance budgets and fund priorities. Mayor Bill de Blasio continued the policies.

The parallels of this human tragedy are all too familiar to San Francisco cab drivers. Former Mayors Gavin Newsom and Ed Lee sold medallions – the licenses that allow an operator to drive a cab — to balance budget deficits. Under Lee’s administration, tens of thousands of quasi-taxi Uber and Lyft vehicles — without medallions — flooded our streets selling rides below cost, which as a result, trapped cab owners with unpayable loans and drove the entire taxi industry into poverty and despair.

Cab drivers protest outside of Uber HQ in San Francisco.

Government officials of that time and subsequent mayoral administrations just stood idly by. Their actions, or the lack thereof, had a profound impact on the lives and careers of cab drivers who — in good faith — invested a lot of money and many years of their lives in the medallion system they treasured as their unofficial retirement pension.

Unfortunately, few media outlets have done in-depth reporting about what led to this decade old tragedy nor has the plight of medallion buyers gotten the attention it deserves.

Just in case you still don’t know, or perhaps, in case you still don’t care, the medallion sales program masterminded by Newsom and carried out by late Lee had one objective only: Take advantage of a money-making opportunity by transforming the distribution of taxi permits in San Francisco into a system similar to that of New York City.

Under their respective administrations — from early 2010 to the spring of 2016 — the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency sold hundreds of medallions for $250,000 each and balanced their budget on the backs of hardworking cab drivers who otherwise would have earned a medallion for almost no cost through the existing waiting-list system.

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

Lyft had already been using private vehicles as on-demand taxis, providing illegal taxi services in the city since May 2012. Uber would soon add an UberX choice to their App to participate in the same activity which then-Uber CEO Travis Kalanick had referred to as “criminal misdemeanor pickups.”

Instead of cracking down on those yet-to-be-regulated app-summoned taxis, Lee questionably shielded these companies from taxi regulations and gave away jurisdiction of these new entrants to the California Public Utilities Commission, a state regulatory agency.

And, instead of halting the medallion sales program. at an August 2012 meeting, the MTA Board — without hesitation — ignored the warnings and rushed to permanently adopt the program, recklessly pushing for more medallion sales until the market crashed in April 2016, trapping more medallion buyers with loans for which they wouldn’t be able to pay.

Long before the CPUC ruled Uber and Lyft Transportation Network Companies, Lee — in an apparent betrayal of his sworn oath to uphold the law in office — embraced both companies in his State of the City Address in January 2013 and later, to celebrate Lyft’s one-year anniversary, proclaimed July 13, 2013 “Lyft Day” in San Francisco.

This brings to mind that Lyft had been operating illegally for more than one year and still got a trophy from the mayor.

And Newsom, the mastermind of the medallion sales program, as lieutenant governor in 2014 – acting without concern for medallion purchasers already committed to medallion loans — urged the California Legislature not to stifle innovation by heavily regulating TNCs.

Newsom and Lee should have known that Uber and Lyft posed a great risk to the medallion sales program and the taxi industry as a whole, and yet again, instead of making objective legal decisions towards a level playing field in the transportation-for-hire market, they chose to support, promote, and facilitate the unfair competition that would kill the medallion market.

For years, cab drivers were misled into buying taxi medallions at the very same time the city opened the doors for a vast oversupply of Ubers and Lyfts to provide the very same taxi service without having to comply with any taxi regulations and without the very same taxi medallions sold to balance the MTA’s budget at cab drivers’ expense.

If that’s not illegal, it should be.

The avoidable clash of the now-defunct medallion sales program with the unregulated rise of Uber and Lyft brought great financial hardship to all medallion purchasers and all medallion holders who acquired their permits before 2010. It has had an adverse effect on the entire taxi industry and it left the MTA’s lending partner holding a bag full of unpayable loans.

In March 2018, the San Francisco Federal Credit Union filed a lawsuit against the MTA over its actions related to the “Program.” The remaining causes of action are: 1) Breach of contract, 2) Breach of Implied Covenant of Good Faith and Fair Dealing. It states:

“The SFMTA repeatedly failed to inform the Credit Union that the City refused to bring TNCs under the SFMTA’s jurisdiction.”

It defies explanation and common sense that the MTA — fully aware of Lee’s position on TNCs — ignored the risks these companies posed to the taxi industry and carried out as many medallion sales for as long as they could in a medallion market bound to fail.

The reality is, the medallion sales program has failed and even though the MTA denies it, most of their policies to reinvigorate the program have failed as well. Not a single medallion has been sold since April 2016. What once was an asset, is now a liability.

Purchased medallions foreclosed upon are more than 270 … and counting. Medallion buyers still trapped with these loans, still trying to make their monthly payments on those devalued, currently worthless medallions, are driving themselves to their graves with no future prospects.

In a futile effort to materially increase income for medallion purchasers, the MTA has implemented several ill-advised policies detrimental to various other industry stakeholders, thereby also reducing public taxi availability.

The “Lyft Day” episode alone shows that the San Francisco is culpable for having had a significant role in the demise of the medallion value, clearly making all medallion holders and the taxi industry the real victims in this multi-million-dollar debacle.

The city’s responsibility is not only to the credit union but all medallion purchasers and all medallion holders who invested decades of their lives in the previous medallion systems. Nevertheless, the credit union is the only plaintiff in the claim; all medallion holders can do is wait and wonder what the outcome of this lawsuit will bring.

And as we wait for a possible trial — already postponed four times — the thought of a jury quashing this litigation, rewarding the city for acting in bad faith and stabbing the taxi industry in the back after using it as a cash cow, brings more fear and anxiety to a long struggling industry.

The situation in which the taxi industry finds itself today does not place it well enough to emerge from this toll-taking COVID pandemic, nor the financial damages caused by the positions taken by Newsom and Lee, nor the complacency of our representatives in the California Legislature who failed to properly regulate TNCs when they should have.

Although the taxi industry is not exempt from AB5, the state law represented a possibility to achieve a level playing field in the market. Now, with the passage of Prop 22, Uber and Lyft are even more emboldened to make a mockery of transportation and labor laws, dump more vehicles on our streets, exploit more drivers, and once again thumb their noses at lawmakers.

To its credit, the City Attorney’s Office is one of the plaintiffs in a lawsuit filed by the state attorney general against Uber and Lyft, enforcing AB5 retroactively. However, the office is also defending the MTA’s actions related to the medallion sales program in the credit union lawsuit.

Ironically, Uber and Lyft still deny being taxi services because they don’t have the rights to street hails. Even more ironic, Lyft rides in some Florida cities — targeting seniors who do not rely on apps — can now be ordered over the phone through an agent, just like a taxi dispatcher. Very possibly, Uber and Lyft will do the same in San Francisco.

If the city wants to only have Uber and Lyft on our streets, handing over 100 percent of taxi services to poorly regulated mega corporations with bad records, perhaps the city should sell them the rights to street hails and phone dispatching to bail out the entire taxi industry and make the credit union whole. Why not make Uber and Lyft pay for this?

And how about autonomous vehicle companies such as Cruise and Waymo testing their “robot-taxis” in San Francisco? Will the city have any jurisdiction over them? If so, will the city require them to buy medallions? If they provide taxi services in the city, why not require them to have taxi medallions as well?

In the wake of The New York Times’ investigations, the City and State of New York took actions to address their medallion crisis. The Attorney General’s Office and the Mayor’s Office opened an inquiry into the medallion loans cab drivers obtained. Recently, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer pledged his support for debt relief for NYC’s struggling cab drivers.

Although it’s not nearly enough and even though New York City could still face an $800-million lawsuit from State Attorney General Letitia James over medallion loans, Mayor Bill de Blasio plans to spend $65 million from the federal stimulus package to restructure loans cab drivers acquired.

There is no relief for medallion buyers in San Francisco. Nonetheless, the MTA is the biggest recipient of a second windfall of $297 million from federal stimulus packages. As yet, there is no money from those stimulus packages allotted to the taxi industry. Medallion holders’ misery, pain and anxiety just linger on.

The truth of the matter still remains: The city didn’t care to protect nor act in good faith with the cab drivers nor the industry they were selling to and profiting from; they took the position to embrace TNCs even before they were given any legitimacy by the CPUC.

Our former mayors allowed Uber and Lyft to go from rogue to mainstream without having to comply with any taxi regulations and without the very same medallions cab drivers were misled into buying. The policies of Newsom and Lee doomed the medallion sales program and crushed the taxi industry as a whole.

The failure of the current medallion system is not to be blamed on the taxi industry. Its failure is a human tragedy that can only be blamed on the City of San Francisco. Therefore, the City of San Francisco must either take responsibility for its actions or be held accountable.

This is an injustice of epic proportions; it must end. Justice for the taxi industry is well deserved and it is long overdue.

Marcelo Fonseca has been a taxi driver for more than 30 years.

SF tried to further damage cab drivers who were tricked into heavy debt

SFMTA wants to take away cab permits from people who paid big money for them just as the city let Uber and Lyft destroy the industry—but Board of Appeals pushes back

https://48hills.org/2023/01/sf-tried-to-further-damage-cab-drivers-who-were-tricked-into-heavy-debt/

By TIM REDMOND

JANUARY 4, 2023

The San Francisco Board of Appeals is pushing back against a move buy the Municipal Transit Agency to block the board from hearing appeals on taxi permit revocations.

It’s an issue that doesn’t much press attention, but for older and disabled people in the beleaguered taxi industry, it’s a huge deal:

After the city allowed Uber and Lyft to decimate the taxi industry, and created a failed market for permits that left many drivers broke and in debt, losing a permit is a devastating financial hit.

Ali Asghar talks about the devastation the city has caused for people who bought medallions in good faith

That’s why the Board of Appeals has overturned a few of those revocations on equity grounds. And instead of changing its policies, the SFMTA is trying to push the appellate board out of the way.

Jeffrey Tumlin, the head of SFMTA, wrote to the Board of Appeals Dec. 5 to unilaterally declare that his agency would no longer allow the independent board to hear cab permit appeals. The board, in a Jan 4 letter, essentially told Tumlin: No.

More than that, the letter suggested that the hearing officers at SFMTA who consider permit appeals are lacking in independence and in some cases have changed their decisions under pressure from management.

The background:

Nobody can operate (and that’s a key word, more on it later) a taxi in San Francisco without a permit, called a medallion. Between 1978 and 2010, the rules were simple: The medallions belonged to the city, and could only be used by active cab drivers. They couldn’t be bought or sold or transferred, and were awarded entirely on seniority: When you started a career as a driver, you put your name on the permit list, and when someone else retired or died, you would move up and eventually, after about 15 years, you would get your own permit.

Now, the permits were good for 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and nobody would drive that much. So for the shifts the permit holder wasn’t working, they could lease the permit to someone else, usually through one of the cab companies.

So the more junior drivers would pay a lease fee to use a permit (and typically to use a car); after covering the so-called “gate fee” and gas, the driver would keep anything left over in fares.

The gates and fares were regulated by the city at a level that allowed the junior drivers to make a decent living. The medallion holders made not only the money they earned from driving but also the lease fees.

The idea: You work for 15 years in the industry, and you get a chance to reap the benefits of a permit. But the rules were clear: You couldn’t just get the permit and sit back and make money; you had to be an active driver to keep it.

Proposition K, the measure that set up the system, was sponsored by then-Sup. Quentin Kopp, who said he wanted to be sure that the public benefit of permit ownership went to the drivers, and that the permits could never be privatized.

In 2010, then-Mayor Gavin Newsom decided that the permits were worth a lot of money, and moved to sell them, essentially at auction. No more waiting in line; anyone with $250,000 could buy a permit, and hold onto it until they sold it, at a market rate, with the city taking a cut. That brough $64 million into the city coffers, but since most drivers had nowhere near that amount of money, they borrowed it, mostly from SF Federal Credit Union.

But just as that move to privatize the permits and put drivers in the hole for big loans happened, Newsom and his successor, Mayor Ed Lee, decided to let Uber and Lyft “disrupt” the industry by operating illegal cabs with no medallions at all.

In a very short period of time, those $250,000 medallions became worthless, the owners in debt, unable to make a living, and unable to sell the asset. Remember: This was not the fault of the drivers who bought medallions, with the understanding that they would be able to pay the debt by driving. The city refused to crack down on the illegal ride-shares, leaving the permit holders with nothing.

So now the cab industry has stabilized a bit, as Uber and Lyft fares have risen and the older companies have adopted the same quality of apps; you can now get a cab from, say, Flywheel, just a fast and at the same or a lower price than Uber. And Flywheel is working on a deal with Uber to share dispatch.

And drivers who bought permits, but have since become disabled or are otherwise unable to drive the (old) required number of shifts, are facing the revocation of their medallions.

That might have made sense in the old days, when you made enough money on a medallion to retire, but under the current system, a driver who can’t work is still stuck with the loan. Under the rules, the city is supposed to buy back the permit for $200,000—but only after it’s resold, and that’s a joke since there is zero market for medallions today.

On Nov. 16, 2022, records show, the board rejected the SFMTA’s decision to revoke the permit of Robert Skrak, who because of multiple disabilities diagnosed in 2012, no longer had a valid California driver’s license and couldn’t drive a cab. His lawyer argued that he could still “operate” a taxi as an owner and manager. More important, Skrak argued, the SFMTA staff repeatedly told him that he could continue to lease his permit until he decided to sell it—which soon became impossible, thanks to the SFMTA’s embrace of ride shares.

But the Board of Appeals took a larger stand:

Allowing him to keep his medallion is necessary to avoid a grave injustice, it would not defeat a strong public policy and would not create any safety issues for the public.

The board voted 5-0 to let Skrak keep his medallion, and his income.

The SFMTA then decided, with the support of City Attorney David Chiu, was to cut the Board of Appeals out of the process.

The board’s director, Julie Rosenberg, with the unanimous support of the members Jan. 4, told Tumlin that the board wanted to continue hearing these types of appeals:

we think it is important for the SFMTA to consider the advantages of the BOA process, which include extensive public input and participation. Having SFMTA taxi matters heard alongside non-SFMTA items on the BOA’s agenda provides a broader audience for such hearings and promotes a higher degree of public exposure to the issues raised in such matters. Similarly, the BOA, as a body existing outside of the SFMTA (the commissioners are appointed by the Mayor and the President of the Board of Supervisors), incorporates diverse viewpoints informed by the commissioners’ collective experience handling and resolving a wide variety of appeals across many San Francisco agencies.

But the letter goes much further, casting doubt on the fairness of the process the SFMTA uses to consider permit appeals:

We also think that the SFMTA should consider recent questions raised about the independence of SFMTA hearing officers. These questions came up in the context of cases where decisions were reconsidered by SFMTA hearing officers after the hearing officers had previously issued decisions that were not favorable to the SFMTA Taxi Division. In each such case, after receiving a decision that overturned the SFMTA Taxi Division’s revocation of a medallion, counsel for the SFMTA reached out directly to the SFMTA hearing officer and requested that he reconsider the decision. The record showed that the hearing officers ultimately changed their decisions after receiving these communications. Given that the communications submitted to the record suggest that several decisions may have been reconsidered by SFMTA hearing officers, a reasonable member of the public might question whether the SFMTA hearing officers are sufficiently independent. Given the composition of the BOA and its existence outside of the SFMTA as noted above, the BOA may have a greater potential of surviving this type of scrutiny by the public. We think you would agree that the appearance of independence and impartiality are important tenets of due process and thus ask that these questions be considered as the SFMTA makes this decision.

That’s a pretty serious problem.

It also puts the city attorney, who was a supporter of Uber and Lyft back in the day, in a bind: He has already sided with the SFMTA, but the Board of Appeals is also his client.

The city could address this easily, by taking that $64 million windfall and paying off the permit holders who were cheated by Mayors Newsom and Lee.

Or this permit appeal battle can continue, with the old, disabled, and broke drivers continuing as pawns in a game they didn’t sign up for.

Uber Is Hurting Drivers Like Me in Its Legal Fight in California

We’re in limbo as the ride-hailing company spends millions fighting a new state law.

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/04/opinion/uber-drivers-california-regulations.html

By Derrick Baker

Mr. Baker is an Uber driver and organizer with Gig Workers Rising.

Sept. 4, 2020, 5:00 a.m. ET

A protest last year outside Uber headquarters in San Francisco. Uber is battling a California law effectively requiring it to treat drivers as employees entitled to benefits.

A protest last year outside Uber headquarters in San Francisco. Uber is battling a California law effectively requiring it to treat drivers as employees entitled to benefits.

Credit...Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

SAN FRANCISCO — I love to drive. Before Uber, I was a car service owner-operator for 10 years and got a thrill out of meeting new people while making my way around San Francisco, a place I’ve called home for over 30 years. I drove my black Mercedes sedan full-time five to six days a week, and counted myself lucky. When my wife died in 2011, I stopped, taking time to grieve.

I first heard about Uber when I came back in 2017. It seemed like a godsend. My friends in the car-service industry were quickly switching to the app, making as much money or more than when they were operating on their own. It felt like a win-win.

In hindsight, I can see it was a classic bait and switch. After undercutting the black-car and taxi industries to direct consumers (and drivers) to Uber, the company turned on us, cannibalizing the very market it helped create.

In my first couple of years driving, Uber announced driver rate cuts that meant the portion of the fare the company kept would be higher than what I took home. After accounting for waiting time and other expenses like gas and wear and tear on my car (all costs I have to cover), I’d be lucky if I got $10 per hour. That’s not even minimum wage in San Francisco. But going back into business for myself as an independent chauffeur wasn’t an option — Uber and other ride-hailing companies had effectively destroyed that job.

That’s why I and my fellow drivers were relieved when California legislators last year passed a law effectively requiring Uber, Lyft and similar companies to extend workplace benefits and protections to drivers, including a minimum wage and paid sick leave. But this is something the companies have refused to do, arguing that we are independent contractors.

Uber has refused to comply even after a California judge ordered it to follow the law. That order was stayed after Uber and Lyft appealed, though nothing about the facts on the ground has changed.

Uber is now spending $30 million on a November ballot initiative in California that would permanently exempt it from nearly every basic state and local labor law, including overtime, paid sick leave and unemployment insurance. On Friday, Uber and Lyft face a court deadline that will require their chief executives to swear, under oath, that they have plans to comply with state law if their ballot initiative fails and the court imposes the original order.

What I have experienced driving for Uber shows why basic worker protections are essential and why the fight over them is so crucial to our livelihoods.

Because of repeated pay cuts and an influx of drivers on the road, I saw friends working 80-hour weeks who could barely make enough money to pay rent. I know drivers who suffered positional stress injuries from hours sitting behind the wheel without a break, and who had no health insurance or workers' compensation. When the pandemic hit, I saw fellow drivers struggle to navigate the unemployment system in California that Uber at one point argued shouldn’t be extended to us, even though the law clearly makes us eligible for benefits.

When workers have had the guts to demand the protections the law ensures, Uber and other ride-hailing companies trot out the familiar line that to improve working conditions, they’d have to reduce the number of drivers and increase fares. But this is clearly misdirection.

While Uber cries out that having to follow the law would hurt its business model, Uber’s leadership curiously neglects to mention the billions of dollars in cash reserves it has told investors it has available or the generous compensation packages offered to its executives.

Uber’s recent threat to suspend operations in California rather than obey a court order was heartless. That suspension didn’t happen because of the last-minute legal reprieve, but I have friends who would have lost their livelihoods and been left scrambling for new work if the company had followed through on its threat.

The company defended its actions by claiming that it was protecting the flexible work arrangements its drivers value. Yet nothing in the law prevents Uber from paying a living wage while offering flexibility.

Yes, being able to jump on the app when I wanted was attractive for a time and many other drivers will tell you the same. But as Uber continues to cut pay, drivers will have to work longer and longer shifts to make the same amount of money, undercutting the idea that the work is truly flexible.

I now suffer from diabetes, and have to undergo dialysis treatments during peak driving hours. Sure, I have the “flexibility” to not work during those times, when my illness prevents me from driving. But it’s a cold comfort since I have no paid leave. To Uber, drivers are just another business cost to be solved for, not human beings who deserve to work with dignity.

Healthy, well-paid drivers would be more loyal to the app, would provide a better passenger experience and could transform the company. I’ve met scores of other drivers who share my perspective. We all want to be able to earn a living wage, be protected at work and be treated fairly under the law.

Instead, Uber is treating us like cannon fodder in its war against regulation. Its threat to shut down was foolish and shortsighted. The company should instead take the long view, invest in its workers and use this moment, when demand is low, to re-envision how it operates.

Ride-hailing companies shouldn’t be allowed to violate our rights because their “business model” depends on it.

Derrick Baker is an Uber driver and organizer with Gig Workers Rising, which supports app workers pursuing better wages and working conditions.

Another Example of the Criminally Corrupt Newsom Whose Appointees Run the PUC And The Cover-up By Democratic Party Politicians In California

She Noticed $200 Million Missing, Then She Was Fired

Alice Stebbins was hired to fix the finances of California’s powerful utility regulator. She was fired after finding $200 million for the state’s deaf, blind and poor residents was missing.

https://www.propublica.org/article/she-noticed-200-million-missing-then-she-was-fired

by Scott Morris, Bay City News Foundation Dec. 24, 2020, 5 a.m. EST

Alice Stebbins, former executive director of the California Public Utilities Commission, outside her former workplace

Alice Stebbins, former executive director of the California Public Utilities Commission, outside her former workplace. (Andri Tambunan, special to ProPublica)

ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive our biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

This article was produced in partnership with Bay City News Foundation, which is a member of the ProPublica Local Reporting Network.

Earlier this year, the governing board of one of California’s most powerful regulatory agencies unleashed troubling accusations against its top employee.

Commissioners with the California Public Utilities Commission, or CPUC, accused Executive Director Alice Stebbins of violating state personnel rules by hiring former colleagues without proper qualifications. They said the agency chief misled the public by asserting that as much as $200 million was missing from accounts intended to fund programs for the state’s blind, deaf and poor. At a hearing in August, Commission President Marybel Batjer said that Stebbins had discredited the CPUC.

“You took a series of actions over the course of several years that calls into question your integrity,” Batjer told Stebbins, who joined the agency in 2018. Those actions, she said, “cause us to have to consider whether you can continue to serve as the leader of this agency.”

The five commissioners voted unanimously to terminate Stebbins, who had worked as an auditor and budget analyst for different state agencies for more than 30 years.

But an investigation by the Bay City News Foundation and ProPublica has found that Stebbins was right about the missing money.

Just days before Stebbins was fired, CPUC officials told California’s Department of Finance that the agency was owed more than $200 million, according to a memo obtained by the news organizations. The finance agency launched an investigation into the uncollected funds.

The news organizations’ investigation also found flaws in the State Personnel Board report that Batjer used to terminate Stebbins. Three former CPUC employees said in interviews that the report contained falsehoods. The report alleged that the auditor who discovered the missing money was unqualified. But hiring materials obtained by the news organizations show that state officials had determined that the auditor was the most qualified candidate, awarding him an “excellent” rating in every category.

Batjer, a former casino executive, was appointed by Gov. Gavin Newsom to lead the commission in July 2019, the same month Stebbins briefed the commissioners on problems with the agency’s accounting practices. Early on, Batjer scrutinized Stebbins’ personnel decisions, according to previously unreported text messages obtained by the news organizations. Shortly after she was sworn in as president in August, Batjer texted a former colleague in Newsom’s cabinet.

Marybel Batjer speaking in 2019, as California Gov. Gavin Newsom looks on. (Rich Pedroncelli/AP Photo)

Batjer told Julie Lee, who was serving as California’s acting secretary of Government Operations, or GovOps, that she was “very concerned”: She believed the auditor was not qualified for the job and was upset that Stebbins had given him a raise after putting him in charge of additional employees. Batjer had previously served as head of GovOps, which oversees the State Personnel Board.

“I find this outrageous!” Batjer wrote to her old colleague. “I’m terribly worried. Thanks much for any advice/help you can get before this gets much worse.”

“Let’s get together and figure this out!” Lee responded. “We will help you fix, don’t stress.”

The commissioners appear to have violated state transparency laws when they later exchanged text messages among themselves about whether to fire Stebbins. California law prohibits the majority of a public body from discussing matters under its jurisdiction outside of a regular meeting, particularly to build a consensus, legal experts said.

“I can’t imagine her remaining,” Batjer wrote a fellow commissioner in a private text message.

Stebbins filed a wrongful termination suit against the CPUC this month. In a series of interviews, the most extensive since her termination, she described an agency mired in disorganization and ineptitude. An experienced administrator, she was recruited by the previous president to clean up a dysfunctional agency. She found some of her employees did not know basic information about the utilities they were supposed to be regulating — in one case, lacking even current contact information for regulated water companies. Audits dating back to 2012 had found ineffective budget management and a need for improved fiscal monitoring.

“You’ve got just systemic issues,” Stebbins said in an interview. “The only way you can make those changes is to really tear it apart.”

Batjer did not respond to requests for an interview. The other commissioners did not return emails seeking comment. The CPUC has not yet responded to Stebbins’ lawsuit. Through a spokesperson, Lee denied that she triggered or influenced the investigation into Stebbins. The State Personnel Board declined to comment on their investigation.

In response to detailed questions, commission spokeswoman Terrie Prosper said that Stebbins’ allegation of $200 million in missing fines and fees was the result of a misunderstanding of the commission’s accounting practices.

Prosper did not address the apparent open meeting violations, citing pending litigation. But she said Stebbins’ manipulation of the hiring process warranted her dismissal. She acknowledged “some inaccuracies” in the state personnel report but dismissed them as “nonsubstantive details.”

“Her allegation that she was dismissed for finding alleged budget irregularities flies in the face of the clear public action taken by the CPUC,” Prosper said.

A Cleanup Job

The CPUC was formed in the early 20th century to regulate railroads. Since then, numerous other industries have been placed under its oversight, including giant electric and gas monopolies, phone companies, water providers and transportation companies like Uber and Lyft, making it one of the most powerful agencies in California.

But in recent years, the CPUC has faced accusations that it has become too cozy with utilities. In 2010, a PG&E gas line exploded in the San Francisco suburb of San Bruno, killed eight and destroyed 30 homes. The CPUC president at the time, a former energy executive, resigned after it was revealed he and his staff were helping a PG&E executive pick the judge for an upcoming rate case.

Stebbins was hired as the agency’s executive director in February 2018 to bring fresh scrutiny to its finances and operations.

Stebbins was disturbed by what she found at the CPUC. Fiscal mismanagement and disorganization made holding utilities accountable impossible, she said. She ordered extensive audits of agency divisions, accounting practices and specialized programs for providing services to impoverished and disabled California residents.

She quickly fired the head of the Water Division, who oversaw 110 investor-owned utilities serving about 6.3 million residents. Stebbins said that the division wasn’t keeping basic records like contact information for the utilities it regulates.

An audit found division staff members were often not conducting required on-site visits and when they did, the inspections were brief and incomplete. When a utility was found out of compliance with regulations, the division rarely issued citations, even when violations persisted. One utility had been collecting fees from ratepayers for 19 years and failing to send the money to the CPUC, Stebbins said.

“It was a nonfunctioning division, and it’s still for the most part nonfunctioning,” Stebbins said.

Millions Past Due

One audit Stebbins ordered found the CPUC was doing a poor job collecting on debts. It found $49.9 million in outstanding collections as of the end of 2019. That included more than $12 million in enforcement fines, more than $22 million in telecommunication fines and more than $14 million in reimbursable contracts. About $21.1 million had been due since before 2017.

“Given that nearly $50 million is owed to the CPUC,” the audit said, “CPUC should investigate whether the program areas utilize appropriate collection efforts against companies with delinquent payments and to what extent follow up occurs.”

In a statement to the news organizations, the CPUC argued that it was aggressively collecting overdue fines and fees but that those efforts were mired in court actions or appeals. In particular, the agency said two defunct companies owed nearly $19.8 million in fines from a 2010 investigation. The matter was taken to court and an appeals court upheld a judgment in the CPUC’s favor in July.

The audit also hinted that there could be much more owed that is not accounted for in the official book of record. For certain surcharges and fees, the CPUC allows companies to self-report what they owe and does not track whether they have paid.

The CPUC headquarters in San Francisco. (Andri Tambunan, special to ProPublica)

In early 2019, Stebbins hired Bernard Azevedo, a former colleague, as director of administrative services. Azevedo had been an accountant with the state for 30 years, most recently as a branch chief for the Air Resources Board. Among other things, Azevedo started looking carefully into the self-reported fees.

What he found shocked him. A large portion of the fees were collected as surcharges on customer bills, particularly phone bills, to fund vital assistance programs for poor and disabled people. But the CPUC was doing a poor job of tracking what the utilities owed, he said. Those in charge of the assistance programs were monitoring the money, rather than the accounting office. So at the end of each fiscal year, accountants simply reset the amount due to zero, assuming the fees had been collected.

Azevedo estimated that the utilities owed the CPUC more than $150 million beyond the $49 million identified in the audit.

“We don’t know what we’re collecting,” Azevedo said in an interview. “We don’t know who’s paying; we don’t know how much they’re paying.”

“I have real concerns,” Azevedo said. “This is a lot of money.”

Azevedo estimated that the Lifeline program, which provides phone service for low-income Californians, could be short $61 million. The Deaf and Disabled Telecommunications Program, which provides devices to people with disabilities, could be missing $6.3 million. The California Teleconnect Fund, which provides low-cost service to schools, libraries, community colleges, hospitals, health clinics and other community organizations, had not received some $10 million owed by utilities.

Stebbins alleges that the agency collected only $21 million in the 2018-19 fiscal year. Its strange accounting practices made it difficult to tell which utilities paid or if they paid the right amount.

“I’ve never seen it done this way by any organization I’ve worked for in 34 years in auditing and accounting for the state,” Stebbins said.

During Stebbins’ termination hearing, Batjer said, “the CPUC did not have $200 million in uncollected fees” and pointed to the audit report, which found only $49.9 million was uncollected.

But a letter from the CPUC’s outside counsel Suzanne Solomon that was sent to Stebbins’ attorneys a few days before Batjer’s remarks contradicted Batjer. Solomon acknowledged an additional $141 million owed as of June 2019 but argued that the CPUC expected to collect those fees the following year.

In a statement, the CPUC alleged that Stebbins and her attorneys made “many false allegations” that “reflected a misunderstanding of the state’s accounting system and methods.”

Stebbins and Azevedo say that they are confident that they had discovered a real problem. But their investigation was cut short when they were both fired. Stebbins said, “I think there’s millions and millions of dollars more out there that have not been reported.”

A New Boss

In April 2020, two investigators with the State Personnel Board contacted Stebbins. They wanted to know about several recent hires. Stebbins didn’t think much of it at the time.

But a month later, an attorney from the state Attorney General’s Office emailed her a draft report from the State Personnel Board that alleged she violated civil service rules and hired former colleagues who weren’t as qualified as other candidates. She was directed to submit a response within a week.

Stebbins was bewildered. She said she found the report wildly inaccurate — she didn’t believe she had violated any civil services rules. She confronted several commissioners. “I had some fairly passionate discussions with commissioners. I honestly could not in any way convince them that the report was incorrect, none of them would listen to me,” Stebbins said. “It was weird because I had a good relationship with the commissioners and all of a sudden I didn’t.”

Text messages reveal the commissioners were already deeply engaged in discussion about her termination. They complained about Stebbins’ behavior and consoled one another emotionally. They seemed taken aback by the vehemence of Stebbins’ arguments.

On July 8, Commissioner Clifford Rechtschaffen wrote to Batjer, “It is clearly apparent that it’s untenable for her to stay working here and we should be working from that assumption.”

Batjer wrote back, “I can’t imagine her remaining.”

Rechtschaffen also wrote, “It’s not tenable for her to stay,” to Commissioner Liane Randolph the same day.

“Poor Marybel is really struggling with this,” Rechtschaffen wrote to Randolph, who was recently nominated to head California’s Air Resources Board.

A text message exchange between two of the CPUC commissioners about Stebbins’ termination. (Obtained from court records)

Under California’s Bagley-Keene Act, it is illegal for a majority of commissioners to discuss an issue among themselves outside of a meeting. It is legal for two commissioners to discuss issues between themselves, but if they relay it to a majority outside of a meeting, it becomes illegal. In the case of the CPUC, a majority is three commissioners.

Public officials who violate the law can face misdemeanor criminal charges, but it is rarely enforced.

“You can’t do anything outside of a public meeting that results in a discussion between a majority,” said Kelly Aviles, an attorney specializing in government transparency. “You can’t do anything indirectly that you can’t do directly.”

Some topics, such as personnel matters, can be withheld from public view by discussing them in a private session, but the closed sessions must be conducted the same way as any other meeting. For a discussion to be private, the members must cite law that allows the topic to be discussed in a closed meeting. “Just because you can discuss something in closed session, it doesn’t allow this kind of free-for-all and you can now discuss it outside of meetings,” Aviles said. “You can’t. You’re bound by the same requirement.”

As the weeks went on, the agreement between the commissioners to fire Stebbins grew stronger. On July 14, Randolph summed up the results of the commissioners’ text stream: “We all agree” to fire Stebbins.

Aviles said that building a consensus outside of a public meeting is also a violation. “You’re not even supposed to be discussing matters that are in the body’s subject matter jurisdiction outside of a public meeting. The fact that they’re coming to a consensus is just the cherry on top,” she said.

Fired

Stebbins was placed on administrative league leave on Aug. 4. A few days later, Batjer took the unusual step of sending the State Personnel Board report to all 1,400 CPUC employees.

Batjer used the report to justify firing Stebbins at the public hearing.

“It is appalling and disgraceful to engineer the hiring of a marginally qualified former colleague over more qualified candidates, spike the person’s pay and then make false statements attempting to justify the compensation,” Batjer said during Stebbins’ termination hearing, making an apparent reference to Azevedo.

But interviews and documents show numerous inaccuracies in the report. For instance, investigators understated Azevedo’s qualifications. Azevedo, the report said, did not have experience with budgets or facilities management. But he had previously served as branch chief at the Air Resources Board for nine years, where he managed a staff of 65, implemented a new fiscal management system and created an internal audit unit. According to Azevedo’s appeal, each other candidate had a decade less experience in government.

Notes from Azevedo’s interview, reviewed by the news organizations, showed his responses were rated “excellent” in all categories, well above the other candidates for his position. The report alleged that the agency’s human resources department later determined that other candidates should have received better scores, but offered no explanation.

As to the raise, Stebbins increased Azevedo’s salary from $10,010 to $14,922 per month after putting him in charge of several additional departments. The personnel board argued that Azevedo wasn’t eligible for such a large raise and the job should have been readvertised.

Batjer went on to accuse Stebbins of trying to cover up her misconduct. “You repeatedly suggested that the commissioners should use our political influence to — in your words — make the SPB report go away,” Batjer said. “The commissioners took an oath to uphold the California Constitution, including the merit system rules, and your suggestion was abhorrent.”

Stebbins acknowledged saying the report should “go away” but said that she had only wanted the commissioners to hear her out and recognize that the report’s allegations were false. Once they did, she thought the issue would go away. “None of it’s relevant, none of it’s real, none of it’s true, and they did not want to listen,” she said.

Private Life

For the first time in more than 30 years, Stebbins now finds herself out of government work.

Her time is spent these days preparing for her lawsuit: cataloging her experiences for her lawyers, filing public records requests and preparing her testimony. But many of her goals remain the same, she said, including effecting change in the agency and uncovering the depth of its fiscal morass.

“A couple people warned me, they said, ‘Be careful, this isn’t going to be favored, people aren’t going to like you, because you’re doing things nobody’s ever done,’” Stebbins said. “When I finally was terminated, one of my team said to me, ‘You’re the first person who came in here, you effectuated change, you made stuff happen, you were cleaning up the organization and they fired you.’”

Mayors Lee and Newsom sold pricey medallions to make money -- then let Uber and Lyft make those investments worthless. The drivers deserve help.

https://48hills.org/.../sf-has-exploited-failed-and.../

By MARCELO FONSECA

APRIL 2, 2021

In 2019, in a series of Pulitzer Prize-winning investigations, The New York Times exposed how government officials stood by as a generation of cab drivers was exploited, victimized by predatory lending, trapped with unpayable loans, and driven to poverty and despair:

New York City in particular failed the taxi industry. Two former mayors, Rudolph W. Giuliani and Michael R. Bloomberg, placed political allies inside the Taxi and Limousine Commission and directed it to sell medallions to help them balance budgets and fund priorities. Mayor Bill de Blasio continued the policies.

The parallels of this human tragedy are all too familiar to San Francisco cab drivers. Former Mayors Gavin Newsom and Ed Lee sold medallions – the licenses that allow an operator to drive a cab — to balance budget deficits. Under Lee’s administration, tens of thousands of quasi-taxi Uber and Lyft vehicles — without medallions — flooded our streets selling rides below cost, which as a result, trapped cab owners with unpayable loans and drove the entire taxi industry into poverty and despair.

Cab drivers protest outside of Uber HQ in San Francisco.

Government officials of that time and subsequent mayoral administrations just stood idly by. Their actions, or the lack thereof, had a profound impact on the lives and careers of cab drivers who — in good faith — invested a lot of money and many years of their lives in the medallion system they treasured as their unofficial retirement pension.

Unfortunately, few media outlets have done in-depth reporting about what led to this decade old tragedy nor has the plight of medallion buyers gotten the attention it deserves.

Just in case you still don’t know, or perhaps, in case you still don’t care, the medallion sales program masterminded by Newsom and carried out by late Lee had one objective only: Take advantage of a money-making opportunity by transforming the distribution of taxi permits in San Francisco into a system similar to that of New York City.

Under their respective administrations — from early 2010 to the spring of 2016 — the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency sold hundreds of medallions for $250,000 each and balanced their budget on the backs of hardworking cab drivers who otherwise would have earned a medallion for almost no cost through the existing waiting-list system.

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

Lyft had already been using private vehicles as on-demand taxis, providing illegal taxi services in the city since May 2012. Uber would soon add an UberX choice to their App to participate in the same activity which then-Uber CEO Travis Kalanick had referred to as “criminal misdemeanor pickups.”

Instead of cracking down on those yet-to-be-regulated app-summoned taxis, Lee questionably shielded these companies from taxi regulations and gave away jurisdiction of these new entrants to the California Public Utilities Commission, a state regulatory agency.

And, instead of halting the medallion sales program. at an August 2012 meeting, the MTA Board — without hesitation — ignored the warnings and rushed to permanently adopt the program, recklessly pushing for more medallion sales until the market crashed in April 2016, trapping more medallion buyers with loans for which they wouldn’t be able to pay.

Long before the CPUC ruled Uber and Lyft Transportation Network Companies, Lee — in an apparent betrayal of his sworn oath to uphold the law in office — embraced both companies in his State of the City Address in January 2013 and later, to celebrate Lyft’s one-year anniversary, proclaimed July 13, 2013 “Lyft Day” in San Francisco.

This brings to mind that Lyft had been operating illegally for more than one year and still got a trophy from the mayor.

And Newsom, the mastermind of the medallion sales program, as lieutenant governor in 2014 – acting without concern for medallion purchasers already committed to medallion loans — urged the California Legislature not to stifle innovation by heavily regulating TNCs.

Newsom and Lee should have known that Uber and Lyft posed a great risk to the medallion sales program and the taxi industry as a whole, and yet again, instead of making objective legal decisions towards a level playing field in the transportation-for-hire market, they chose to support, promote, and facilitate the unfair competition that would kill the medallion market.

For years, cab drivers were misled into buying taxi medallions at the very same time the city opened the doors for a vast oversupply of Ubers and Lyfts to provide the very same taxi service without having to comply with any taxi regulations and without the very same taxi medallions sold to balance the MTA’s budget at cab drivers’ expense.

If that’s not illegal, it should be.

The avoidable clash of the now-defunct medallion sales program with the unregulated rise of Uber and Lyft brought great financial hardship to all medallion purchasers and all medallion holders who acquired their permits before 2010. It has had an adverse effect on the entire taxi industry and it left the MTA’s lending partner holding a bag full of unpayable loans.

In March 2018, the San Francisco Federal Credit Union filed a lawsuit against the MTA over its actions related to the “Program.” The remaining causes of action are: 1) Breach of contract, 2) Breach of Implied Covenant of Good Faith and Fair Dealing. It states:

“The SFMTA repeatedly failed to inform the Credit Union that the City refused to bring TNCs under the SFMTA’s jurisdiction.”

It defies explanation and common sense that the MTA — fully aware of Lee’s position on TNCs — ignored the risks these companies posed to the taxi industry and carried out as many medallion sales for as long as they could in a medallion market bound to fail.

The reality is, the medallion sales program has failed and even though the MTA denies it, most of their policies to reinvigorate the program have failed as well. Not a single medallion has been sold since April 2016. What once was an asset, is now a liability.

Purchased medallions foreclosed upon are more than 270 … and counting. Medallion buyers still trapped with these loans, still trying to make their monthly payments on those devalued, currently worthless medallions, are driving themselves to their graves with no future prospects.

In a futile effort to materially increase income for medallion purchasers, the MTA has implemented several ill-advised policies detrimental to various other industry stakeholders, thereby also reducing public taxi availability.

The “Lyft Day” episode alone shows that the San Francisco is culpable for having had a significant role in the demise of the medallion value, clearly making all medallion holders and the taxi industry the real victims in this multi-million-dollar debacle.

The city’s responsibility is not only to the credit union but all medallion purchasers and all medallion holders who invested decades of their lives in the previous medallion systems. Nevertheless, the credit union is the only plaintiff in the claim; all medallion holders can do is wait and wonder what the outcome of this lawsuit will bring.

And as we wait for a possible trial — already postponed four times — the thought of a jury quashing this litigation, rewarding the city for acting in bad faith and stabbing the taxi industry in the back after using it as a cash cow, brings more fear and anxiety to a long struggling industry.

The situation in which the taxi industry finds itself today does not place it well enough to emerge from this toll-taking COVID pandemic, nor the financial damages caused by the positions taken by Newsom and Lee, nor the complacency of our representatives in the California Legislature who failed to properly regulate TNCs when they should have.

Although the taxi industry is not exempt from AB5, the state law represented a possibility to achieve a level playing field in the market. Now, with the passage of Prop 22, Uber and Lyft are even more emboldened to make a mockery of transportation and labor laws, dump more vehicles on our streets, exploit more drivers, and once again thumb their noses at lawmakers.

To its credit, the City Attorney’s Office is one of the plaintiffs in a lawsuit filed by the state attorney general against Uber and Lyft, enforcing AB5 retroactively. However, the office is also defending the MTA’s actions related to the medallion sales program in the credit union lawsuit.

Ironically, Uber and Lyft still deny being taxi services because they don’t have the rights to street hails. Even more ironic, Lyft rides in some Florida cities — targeting seniors who do not rely on apps — can now be ordered over the phone through an agent, just like a taxi dispatcher. Very possibly, Uber and Lyft will do the same in San Francisco.

If the city wants to only have Uber and Lyft on our streets, handing over 100 percent of taxi services to poorly regulated mega corporations with bad records, perhaps the city should sell them the rights to street hails and phone dispatching to bail out the entire taxi industry and make the credit union whole. Why not make Uber and Lyft pay for this?

And how about autonomous vehicle companies such as Cruise and Waymo testing their “robot-taxis” in San Francisco? Will the city have any jurisdiction over them? If so, will the city require them to buy medallions? If they provide taxi services in the city, why not require them to have taxi medallions as well?

In the wake of The New York Times’ investigations, the City and State of New York took actions to address their medallion crisis. The Attorney General’s Office and the Mayor’s Office opened an inquiry into the medallion loans cab drivers obtained. Recently, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer pledged his support for debt relief for NYC’s struggling cab drivers.

Although it’s not nearly enough and even though New York City could still face an $800-million lawsuit from State Attorney General Letitia James over medallion loans, Mayor Bill de Blasio plans to spend $65 million from the federal stimulus package to restructure loans cab drivers acquired.

There is no relief for medallion buyers in San Francisco. Nonetheless, the MTA is the biggest recipient of a second windfall of $297 million from federal stimulus packages. As yet, there is no money from those stimulus packages allotted to the taxi industry. Medallion holders’ misery, pain and anxiety just linger on.

The truth of the matter still remains: The city didn’t care to protect nor act in good faith with the cab drivers nor the industry they were selling to and profiting from; they took the position to embrace TNCs even before they were given any legitimacy by the CPUC.

Our former mayors allowed Uber and Lyft to go from rogue to mainstream without having to comply with any taxi regulations and without the very same medallions cab drivers were misled into buying. The policies of Newsom and Lee doomed the medallion sales program and crushed the taxi industry as a whole.

The failure of the current medallion system is not to be blamed on the taxi industry. Its failure is a human tragedy that can only be blamed on the City of San Francisco. Therefore, the City of San Francisco must either take responsibility for its actions or be held accountable.

This is an injustice of epic proportions; it must end. Justice for the taxi industry is well deserved and it is long overdue.

Marcelo Fonseca has been a taxi driver for more than 30 years.

SF tried to further damage cab drivers who were tricked into heavy debt

SFMTA wants to take away cab permits from people who paid big money for them just as the city let Uber and Lyft destroy the industry—but Board of Appeals pushes back

https://48hills.org/2023/01/sf-tried-to-further-damage-cab-drivers-who-were-tricked-into-heavy-debt/

By TIM REDMOND

JANUARY 4, 2023

The San Francisco Board of Appeals is pushing back against a move buy the Municipal Transit Agency to block the board from hearing appeals on taxi permit revocations.

It’s an issue that doesn’t much press attention, but for older and disabled people in the beleaguered taxi industry, it’s a huge deal:

After the city allowed Uber and Lyft to decimate the taxi industry, and created a failed market for permits that left many drivers broke and in debt, losing a permit is a devastating financial hit.

Ali Asghar talks about the devastation the city has caused for people who bought medallions in good faith

That’s why the Board of Appeals has overturned a few of those revocations on equity grounds. And instead of changing its policies, the SFMTA is trying to push the appellate board out of the way.

Jeffrey Tumlin, the head of SFMTA, wrote to the Board of Appeals Dec. 5 to unilaterally declare that his agency would no longer allow the independent board to hear cab permit appeals. The board, in a Jan 4 letter, essentially told Tumlin: No.

More than that, the letter suggested that the hearing officers at SFMTA who consider permit appeals are lacking in independence and in some cases have changed their decisions under pressure from management.

The background:

Nobody can operate (and that’s a key word, more on it later) a taxi in San Francisco without a permit, called a medallion. Between 1978 and 2010, the rules were simple: The medallions belonged to the city, and could only be used by active cab drivers. They couldn’t be bought or sold or transferred, and were awarded entirely on seniority: When you started a career as a driver, you put your name on the permit list, and when someone else retired or died, you would move up and eventually, after about 15 years, you would get your own permit.

Now, the permits were good for 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and nobody would drive that much. So for the shifts the permit holder wasn’t working, they could lease the permit to someone else, usually through one of the cab companies.

So the more junior drivers would pay a lease fee to use a permit (and typically to use a car); after covering the so-called “gate fee” and gas, the driver would keep anything left over in fares.

The gates and fares were regulated by the city at a level that allowed the junior drivers to make a decent living. The medallion holders made not only the money they earned from driving but also the lease fees.

The idea: You work for 15 years in the industry, and you get a chance to reap the benefits of a permit. But the rules were clear: You couldn’t just get the permit and sit back and make money; you had to be an active driver to keep it.

Proposition K, the measure that set up the system, was sponsored by then-Sup. Quentin Kopp, who said he wanted to be sure that the public benefit of permit ownership went to the drivers, and that the permits could never be privatized.

In 2010, then-Mayor Gavin Newsom decided that the permits were worth a lot of money, and moved to sell them, essentially at auction. No more waiting in line; anyone with $250,000 could buy a permit, and hold onto it until they sold it, at a market rate, with the city taking a cut. That brough $64 million into the city coffers, but since most drivers had nowhere near that amount of money, they borrowed it, mostly from SF Federal Credit Union.

But just as that move to privatize the permits and put drivers in the hole for big loans happened, Newsom and his successor, Mayor Ed Lee, decided to let Uber and Lyft “disrupt” the industry by operating illegal cabs with no medallions at all.

In a very short period of time, those $250,000 medallions became worthless, the owners in debt, unable to make a living, and unable to sell the asset. Remember: This was not the fault of the drivers who bought medallions, with the understanding that they would be able to pay the debt by driving. The city refused to crack down on the illegal ride-shares, leaving the permit holders with nothing.

So now the cab industry has stabilized a bit, as Uber and Lyft fares have risen and the older companies have adopted the same quality of apps; you can now get a cab from, say, Flywheel, just a fast and at the same or a lower price than Uber. And Flywheel is working on a deal with Uber to share dispatch.

And drivers who bought permits, but have since become disabled or are otherwise unable to drive the (old) required number of shifts, are facing the revocation of their medallions.

That might have made sense in the old days, when you made enough money on a medallion to retire, but under the current system, a driver who can’t work is still stuck with the loan. Under the rules, the city is supposed to buy back the permit for $200,000—but only after it’s resold, and that’s a joke since there is zero market for medallions today.

On Nov. 16, 2022, records show, the board rejected the SFMTA’s decision to revoke the permit of Robert Skrak, who because of multiple disabilities diagnosed in 2012, no longer had a valid California driver’s license and couldn’t drive a cab. His lawyer argued that he could still “operate” a taxi as an owner and manager. More important, Skrak argued, the SFMTA staff repeatedly told him that he could continue to lease his permit until he decided to sell it—which soon became impossible, thanks to the SFMTA’s embrace of ride shares.

But the Board of Appeals took a larger stand:

Allowing him to keep his medallion is necessary to avoid a grave injustice, it would not defeat a strong public policy and would not create any safety issues for the public.

The board voted 5-0 to let Skrak keep his medallion, and his income.

The SFMTA then decided, with the support of City Attorney David Chiu, was to cut the Board of Appeals out of the process.

The board’s director, Julie Rosenberg, with the unanimous support of the members Jan. 4, told Tumlin that the board wanted to continue hearing these types of appeals:

we think it is important for the SFMTA to consider the advantages of the BOA process, which include extensive public input and participation. Having SFMTA taxi matters heard alongside non-SFMTA items on the BOA’s agenda provides a broader audience for such hearings and promotes a higher degree of public exposure to the issues raised in such matters. Similarly, the BOA, as a body existing outside of the SFMTA (the commissioners are appointed by the Mayor and the President of the Board of Supervisors), incorporates diverse viewpoints informed by the commissioners’ collective experience handling and resolving a wide variety of appeals across many San Francisco agencies.

But the letter goes much further, casting doubt on the fairness of the process the SFMTA uses to consider permit appeals:

We also think that the SFMTA should consider recent questions raised about the independence of SFMTA hearing officers. These questions came up in the context of cases where decisions were reconsidered by SFMTA hearing officers after the hearing officers had previously issued decisions that were not favorable to the SFMTA Taxi Division. In each such case, after receiving a decision that overturned the SFMTA Taxi Division’s revocation of a medallion, counsel for the SFMTA reached out directly to the SFMTA hearing officer and requested that he reconsider the decision. The record showed that the hearing officers ultimately changed their decisions after receiving these communications. Given that the communications submitted to the record suggest that several decisions may have been reconsidered by SFMTA hearing officers, a reasonable member of the public might question whether the SFMTA hearing officers are sufficiently independent. Given the composition of the BOA and its existence outside of the SFMTA as noted above, the BOA may have a greater potential of surviving this type of scrutiny by the public. We think you would agree that the appearance of independence and impartiality are important tenets of due process and thus ask that these questions be considered as the SFMTA makes this decision.

That’s a pretty serious problem.

It also puts the city attorney, who was a supporter of Uber and Lyft back in the day, in a bind: He has already sided with the SFMTA, but the Board of Appeals is also his client.

The city could address this easily, by taking that $64 million windfall and paying off the permit holders who were cheated by Mayors Newsom and Lee.

Or this permit appeal battle can continue, with the old, disabled, and broke drivers continuing as pawns in a game they didn’t sign up for.

Uber Is Hurting Drivers Like Me in Its Legal Fight in California

We’re in limbo as the ride-hailing company spends millions fighting a new state law.

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/04/opinion/uber-drivers-california-regulations.html

By Derrick Baker

Mr. Baker is an Uber driver and organizer with Gig Workers Rising.

Sept. 4, 2020, 5:00 a.m. ET

A protest last year outside Uber headquarters in San Francisco. Uber is battling a California law effectively requiring it to treat drivers as employees entitled to benefits.

A protest last year outside Uber headquarters in San Francisco. Uber is battling a California law effectively requiring it to treat drivers as employees entitled to benefits.

Credit...Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

SAN FRANCISCO — I love to drive. Before Uber, I was a car service owner-operator for 10 years and got a thrill out of meeting new people while making my way around San Francisco, a place I’ve called home for over 30 years. I drove my black Mercedes sedan full-time five to six days a week, and counted myself lucky. When my wife died in 2011, I stopped, taking time to grieve.

I first heard about Uber when I came back in 2017. It seemed like a godsend. My friends in the car-service industry were quickly switching to the app, making as much money or more than when they were operating on their own. It felt like a win-win.

In hindsight, I can see it was a classic bait and switch. After undercutting the black-car and taxi industries to direct consumers (and drivers) to Uber, the company turned on us, cannibalizing the very market it helped create.

In my first couple of years driving, Uber announced driver rate cuts that meant the portion of the fare the company kept would be higher than what I took home. After accounting for waiting time and other expenses like gas and wear and tear on my car (all costs I have to cover), I’d be lucky if I got $10 per hour. That’s not even minimum wage in San Francisco. But going back into business for myself as an independent chauffeur wasn’t an option — Uber and other ride-hailing companies had effectively destroyed that job.

That’s why I and my fellow drivers were relieved when California legislators last year passed a law effectively requiring Uber, Lyft and similar companies to extend workplace benefits and protections to drivers, including a minimum wage and paid sick leave. But this is something the companies have refused to do, arguing that we are independent contractors.

Uber has refused to comply even after a California judge ordered it to follow the law. That order was stayed after Uber and Lyft appealed, though nothing about the facts on the ground has changed.

Uber is now spending $30 million on a November ballot initiative in California that would permanently exempt it from nearly every basic state and local labor law, including overtime, paid sick leave and unemployment insurance. On Friday, Uber and Lyft face a court deadline that will require their chief executives to swear, under oath, that they have plans to comply with state law if their ballot initiative fails and the court imposes the original order.

What I have experienced driving for Uber shows why basic worker protections are essential and why the fight over them is so crucial to our livelihoods.

Because of repeated pay cuts and an influx of drivers on the road, I saw friends working 80-hour weeks who could barely make enough money to pay rent. I know drivers who suffered positional stress injuries from hours sitting behind the wheel without a break, and who had no health insurance or workers' compensation. When the pandemic hit, I saw fellow drivers struggle to navigate the unemployment system in California that Uber at one point argued shouldn’t be extended to us, even though the law clearly makes us eligible for benefits.

When workers have had the guts to demand the protections the law ensures, Uber and other ride-hailing companies trot out the familiar line that to improve working conditions, they’d have to reduce the number of drivers and increase fares. But this is clearly misdirection.

While Uber cries out that having to follow the law would hurt its business model, Uber’s leadership curiously neglects to mention the billions of dollars in cash reserves it has told investors it has available or the generous compensation packages offered to its executives.

Uber’s recent threat to suspend operations in California rather than obey a court order was heartless. That suspension didn’t happen because of the last-minute legal reprieve, but I have friends who would have lost their livelihoods and been left scrambling for new work if the company had followed through on its threat.

The company defended its actions by claiming that it was protecting the flexible work arrangements its drivers value. Yet nothing in the law prevents Uber from paying a living wage while offering flexibility.

Yes, being able to jump on the app when I wanted was attractive for a time and many other drivers will tell you the same. But as Uber continues to cut pay, drivers will have to work longer and longer shifts to make the same amount of money, undercutting the idea that the work is truly flexible.

I now suffer from diabetes, and have to undergo dialysis treatments during peak driving hours. Sure, I have the “flexibility” to not work during those times, when my illness prevents me from driving. But it’s a cold comfort since I have no paid leave. To Uber, drivers are just another business cost to be solved for, not human beings who deserve to work with dignity.

Healthy, well-paid drivers would be more loyal to the app, would provide a better passenger experience and could transform the company. I’ve met scores of other drivers who share my perspective. We all want to be able to earn a living wage, be protected at work and be treated fairly under the law.

Instead, Uber is treating us like cannon fodder in its war against regulation. Its threat to shut down was foolish and shortsighted. The company should instead take the long view, invest in its workers and use this moment, when demand is low, to re-envision how it operates.

Ride-hailing companies shouldn’t be allowed to violate our rights because their “business model” depends on it.

Derrick Baker is an Uber driver and organizer with Gig Workers Rising, which supports app workers pursuing better wages and working conditions.

Another Example of the Criminally Corrupt Newsom Whose Appointees Run the PUC And The Cover-up By Democratic Party Politicians In California

She Noticed $200 Million Missing, Then She Was Fired

Alice Stebbins was hired to fix the finances of California’s powerful utility regulator. She was fired after finding $200 million for the state’s deaf, blind and poor residents was missing.

https://www.propublica.org/article/she-noticed-200-million-missing-then-she-was-fired

by Scott Morris, Bay City News Foundation Dec. 24, 2020, 5 a.m. EST

Alice Stebbins, former executive director of the California Public Utilities Commission, outside her former workplace

Alice Stebbins, former executive director of the California Public Utilities Commission, outside her former workplace. (Andri Tambunan, special to ProPublica)

ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive our biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

This article was produced in partnership with Bay City News Foundation, which is a member of the ProPublica Local Reporting Network.

Earlier this year, the governing board of one of California’s most powerful regulatory agencies unleashed troubling accusations against its top employee.

Commissioners with the California Public Utilities Commission, or CPUC, accused Executive Director Alice Stebbins of violating state personnel rules by hiring former colleagues without proper qualifications. They said the agency chief misled the public by asserting that as much as $200 million was missing from accounts intended to fund programs for the state’s blind, deaf and poor. At a hearing in August, Commission President Marybel Batjer said that Stebbins had discredited the CPUC.