From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

Becoming the People Our Parents Warned us Against...

This is an article written for the Community Alliance newspaper in anticipation of the Reuniting for Peace and Justice: 50 Years of Resistance event on June 22 at 2 p.m. at the Unitarian Universalist church in Fresno. 2672 E Alluvial Ave.

Becoming the People Our Parents Warned us Against...

Fighting Against the War in Fresno 50 Years Ago

By Joel D. Eis

“A slave is a person who waits for someone else to free them.”

—Frederick Douglass, 19th century African American freedom fighter

It was in a different galaxy, a long, long time ago. Everyone thinks the 1960s was paisley outfits, tie dye, drugs and Jimi Hendrix music. But for those of us who were full-time, boots-on-the ground, antiwar and civil rights activists, things were a far cry from this picture.

Sure, we were part of the general spirit of the 1960s and all that went along with it, but much of that was relief therapy for what we did the other 80% of our time.

From 1968 to 1970, the core of the resistance movement group in Fresno lived and worked in a compound of four farm houses nestled in a fig orchard two miles northwest of Fresno State, on First Avenue just south of Herndon. The people in the tract homes out there now must be seeing some pretty weird ghosts.

We dedicated every breathing moment to enading an unjust and unnecessary war that was bleeding us in every way. Thousands of young men died. Millions of Vietnamese died. Families were torn apart, our national wealth was squandered and we were poisoning thousands of square miles of Southeast Asia with cancer-causing chemicals.

The war fell upon the bodies of working-class young men and women and their families while stockbrokers and rich Republicans danced for joy as the Dow Jones average went up along with the obscene body count.

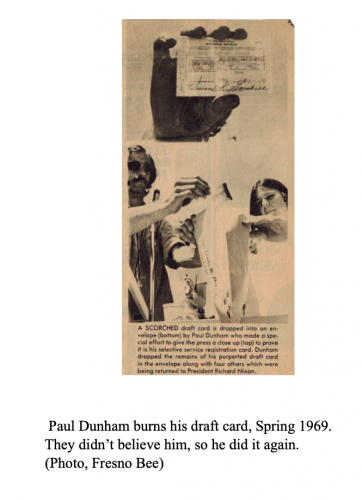

Stopping this insanity became our war at home. It was fought family-by-family. My father told me, “If you burn your draft card you’re no son of mine.” Millions of us were victims of this little father/son disinheritance.

We had become the people our parents had warned us against.

Nevertheless, we were winning. By the dozens, then the hundreds, then the thousands, young men refused induction, burned or turned in their draft cards, fled to Canada or went to prison. The national organizer of all this was David Harris, a former student from Fresno High.

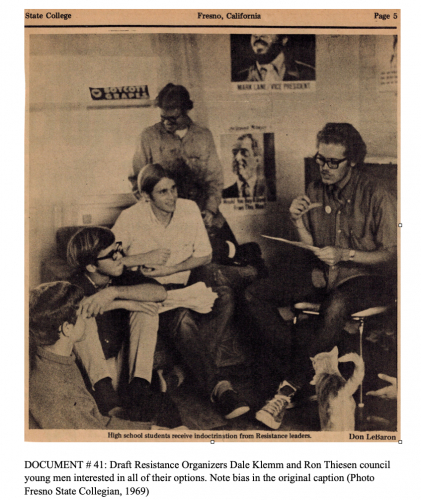

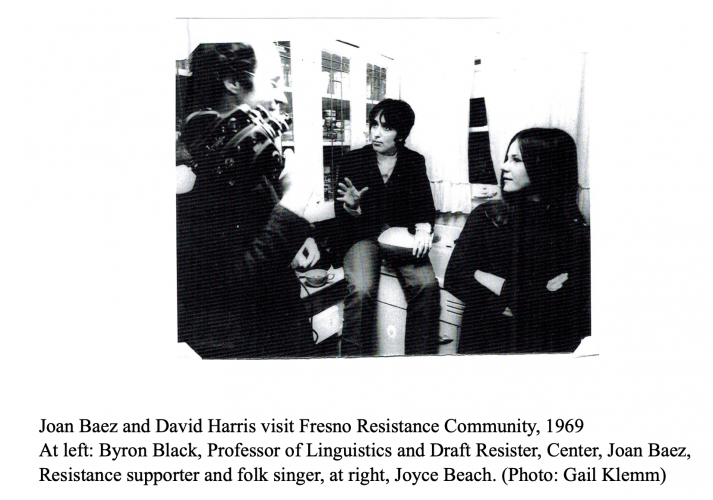

In one house at the compound lived Dale and Gail Klemm. Their place was the office and the printing press. We gathered in this house every Monday night for potlucks and social-style organizing. Harris and his wife, Joan Baez, were occasional visitors. Every now and then, we got a bomb threat and had to move the press somewhere else. Gail would take her baby son and crash somewhere.

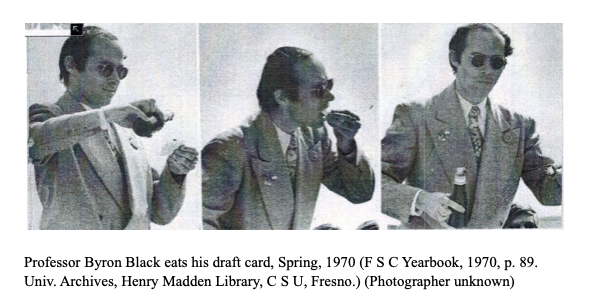

The other houses all held draft resisters and organizers of various stripes. In the front house were two students and even a teacher, Byron Black, who actually ate his draft card in the first act of political performance art I’d ever seen

I lived in the house across from the Klemms, with Patrick Conroy and Paul Dunham. We hosted a constant stream of crashers. Sometimes it was AWOL soldiers who didn’t want to fight or draftees on their way to Canada. Sometimes it was just a friend too stoned to drive home.

We lived on food stamps, odd jobs, stretched-out student loans and unemployment insurance. The joke was that we were just waiting for the box of gold bars from the Kremlin.

We might have been tucked away in an idyllic setting, but the government knew where we were. We never kept drugs in or near our houses or cars. There were too many snitches to set us up for a bust.

A camera with a giant telephoto lens was permanently mounted on the water tower at Fresno State and pointed right at our front lawn. A call to the phone company to complain that the wiretaps were causing disconnected calls netted the following response: “Uh, you must be out at the Resistance House. The taps shouldn’t interfere with your calls”(!).

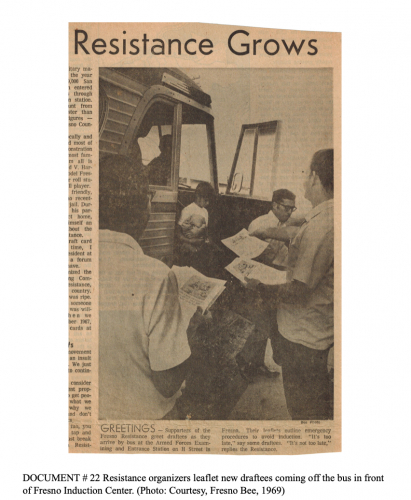

We held rallies on the Fresno State campus every Friday afternoon. Twice a week we went to the recruiting centers to leaflet the boys getting their physicals.

We joined union picket lines and attended draft-resister court cases that included many of our friends. We organized and attended marches and sit-ins. Not a few of us burned our draft cards or sent them back to the government.

Several of our members were full-time members of El Teatro Campesino, the famous theater company that supported the grape boycott. I was one of these. Because of this connection I draft counseled Cesar Chavez’s son.

We were not adverse to a prank now and then. On one priceless occasion, Dale Klemm and a few of the others went on a Sunday and flew the Draft Resistance flag over the U.S. Army Induction Center.

On occasion, we discovered right-wing snipers taking shots at the house. After a phone call, the Brown Berets Chicano community defense group came out and “discussed this” with them. A few of the snipers fell down a few times during these chats. The clumsy fellows were relieved of their weapons. The sniper attacks stopped.

All of this didn’t leave us a hell of a lot of time for partying, but we did our share. Much of our party attendance was actually political contact opportunities. Everyone was talking about the war. We just had a more focused “rap.”

We never went to a party without a pocket full of leaflets. We cornered young men willing to rap about the war and ending it. Hell, most of us event rapped politics in bed.

As the war escalated, the Draft Resistance Movement became more effective. Millions came out in the streets. Soldiers coming home from Vietnam threw their medals back at the capitol building and told the truth about the war. We were winning, and the warmongers were in serious clusterfuck. Their reaction was to increase the harassment.

One Saturday morning, I was in my room and Paul’s pretty young girlfriend was sleeping upstairs. We heard a terrible thump-thump-thump-thump outside. A U.S. Army helicopter was circling the compound perhaps 200 feet off the ground. A soldier was strapped in the open side door taking pictures of the compound.

Karen said, “I know how to get them to come closer.” She went out on the roof and slowly took off her blouse, showing the soldier with the camera what it was he was fighting to protect. The chopper came down so close I could almost read the soldier’s name tag on his shirt.

Then Karen reached into the window of Paul’s bedroom next to the roof and pulled out an M-1 automatic rifle. I didn’t know he had a weapon. She fired off a dozen rounds at the chopper. They pulled away as fast as they could.

Cool as can be, she said, “If they’re gonna treat us like the enemy then I guess this is a combat situation.”

“What the hell!” I said. “Now the cops are gonna show up, big time!”

“Doubt it,” she said. “They’d have to explain what an Army chopper was doing harassing American citizens in the middle of a fig orchard.”

She was right.

On May 4, 1970, four students were murdered by the National Guard at Kent State University and two were killed by state troopers at Jackson State in Mississippi. Two days later, more than 800 universities went on spontaneous strikes across the country.

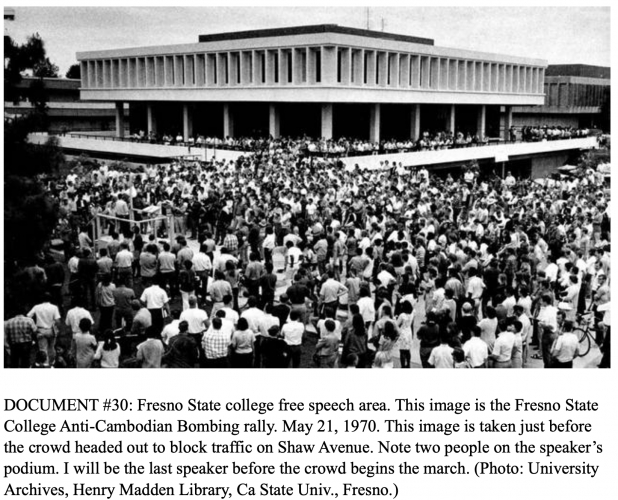

A few thousand of us marched off the Fresno State campus to Shaw Avenue and shut it down. From the crowd of thousands, the cops charged in and handpicked the leaders recognized from their surveillance photos. Forty-seven of us were busted, most on misdemeanor charges.

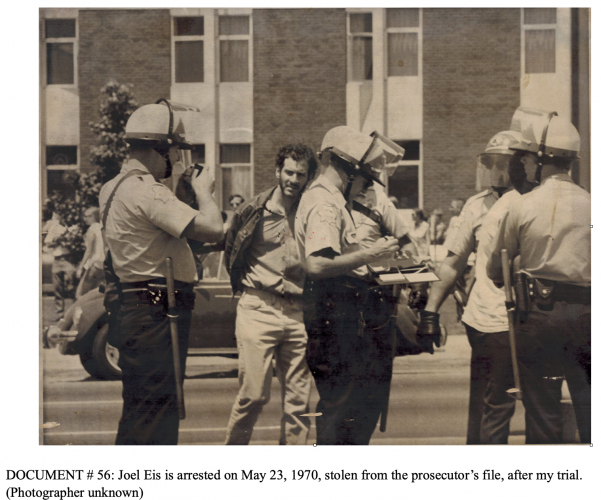

I was treated to two felony counts of possession of a deadly weapon: a pair of round-nosed bandage scissors in a Walgreens first-aid kit and a carabineer used to hold my crash helmet to my belt in case of a cop-riot.

I did a week in jail and was blackballed from a long list of jobs. However, there was a silver lining. I was also issued a special 1-W deferment by the draft board, not to be taken into the Army unless we were invaded. My lawyer said they only do that if they’re afraid you’ll become an organizer in the Army.

When the war was finally over in 1974, we expected to return to ordinary life, get jobs and blend in. I discovered this was not possible.

Just like the soldiers who had fought for their country overseas, we had set aside the pursuit of self-directed careers and fought for a vision of a future at home. In 1978, I discovered I was still disoriented, suffering from a delayed case of something like combat stress disorder.

I and my brothers and sisters in this struggle would never return to take up a “normal” life. Almost all of us continued to stay active in politics raising hell one way or another to this day.

There is an old Russian revolutionary proverb: “Do you know how to make a Thief’s Omelet?”

“First, you must steal two eggs.”

No one else is going to do this for you. Your time will come.

*****

Joel D. Eis began life as a “Red Diaper Baby” in a leftist family. After participating in the Student Strike of 1968 at San Francisco State, he became a Conscientious Objector to the draft and a member of El Teatro Campesino, while organizing again the war in Fresno and San Jose. After spending 45 years as theatre teacher and professional designer, he now owns and operates the Rebound Bookstore in San Rafael with his stunning wife, Toni.

Fighting Against the War in Fresno 50 Years Ago

By Joel D. Eis

“A slave is a person who waits for someone else to free them.”

—Frederick Douglass, 19th century African American freedom fighter

It was in a different galaxy, a long, long time ago. Everyone thinks the 1960s was paisley outfits, tie dye, drugs and Jimi Hendrix music. But for those of us who were full-time, boots-on-the ground, antiwar and civil rights activists, things were a far cry from this picture.

Sure, we were part of the general spirit of the 1960s and all that went along with it, but much of that was relief therapy for what we did the other 80% of our time.

From 1968 to 1970, the core of the resistance movement group in Fresno lived and worked in a compound of four farm houses nestled in a fig orchard two miles northwest of Fresno State, on First Avenue just south of Herndon. The people in the tract homes out there now must be seeing some pretty weird ghosts.

We dedicated every breathing moment to enading an unjust and unnecessary war that was bleeding us in every way. Thousands of young men died. Millions of Vietnamese died. Families were torn apart, our national wealth was squandered and we were poisoning thousands of square miles of Southeast Asia with cancer-causing chemicals.

The war fell upon the bodies of working-class young men and women and their families while stockbrokers and rich Republicans danced for joy as the Dow Jones average went up along with the obscene body count.

Stopping this insanity became our war at home. It was fought family-by-family. My father told me, “If you burn your draft card you’re no son of mine.” Millions of us were victims of this little father/son disinheritance.

We had become the people our parents had warned us against.

Nevertheless, we were winning. By the dozens, then the hundreds, then the thousands, young men refused induction, burned or turned in their draft cards, fled to Canada or went to prison. The national organizer of all this was David Harris, a former student from Fresno High.

In one house at the compound lived Dale and Gail Klemm. Their place was the office and the printing press. We gathered in this house every Monday night for potlucks and social-style organizing. Harris and his wife, Joan Baez, were occasional visitors. Every now and then, we got a bomb threat and had to move the press somewhere else. Gail would take her baby son and crash somewhere.

The other houses all held draft resisters and organizers of various stripes. In the front house were two students and even a teacher, Byron Black, who actually ate his draft card in the first act of political performance art I’d ever seen

I lived in the house across from the Klemms, with Patrick Conroy and Paul Dunham. We hosted a constant stream of crashers. Sometimes it was AWOL soldiers who didn’t want to fight or draftees on their way to Canada. Sometimes it was just a friend too stoned to drive home.

We lived on food stamps, odd jobs, stretched-out student loans and unemployment insurance. The joke was that we were just waiting for the box of gold bars from the Kremlin.

We might have been tucked away in an idyllic setting, but the government knew where we were. We never kept drugs in or near our houses or cars. There were too many snitches to set us up for a bust.

A camera with a giant telephoto lens was permanently mounted on the water tower at Fresno State and pointed right at our front lawn. A call to the phone company to complain that the wiretaps were causing disconnected calls netted the following response: “Uh, you must be out at the Resistance House. The taps shouldn’t interfere with your calls”(!).

We held rallies on the Fresno State campus every Friday afternoon. Twice a week we went to the recruiting centers to leaflet the boys getting their physicals.

We joined union picket lines and attended draft-resister court cases that included many of our friends. We organized and attended marches and sit-ins. Not a few of us burned our draft cards or sent them back to the government.

Several of our members were full-time members of El Teatro Campesino, the famous theater company that supported the grape boycott. I was one of these. Because of this connection I draft counseled Cesar Chavez’s son.

We were not adverse to a prank now and then. On one priceless occasion, Dale Klemm and a few of the others went on a Sunday and flew the Draft Resistance flag over the U.S. Army Induction Center.

On occasion, we discovered right-wing snipers taking shots at the house. After a phone call, the Brown Berets Chicano community defense group came out and “discussed this” with them. A few of the snipers fell down a few times during these chats. The clumsy fellows were relieved of their weapons. The sniper attacks stopped.

All of this didn’t leave us a hell of a lot of time for partying, but we did our share. Much of our party attendance was actually political contact opportunities. Everyone was talking about the war. We just had a more focused “rap.”

We never went to a party without a pocket full of leaflets. We cornered young men willing to rap about the war and ending it. Hell, most of us event rapped politics in bed.

As the war escalated, the Draft Resistance Movement became more effective. Millions came out in the streets. Soldiers coming home from Vietnam threw their medals back at the capitol building and told the truth about the war. We were winning, and the warmongers were in serious clusterfuck. Their reaction was to increase the harassment.

One Saturday morning, I was in my room and Paul’s pretty young girlfriend was sleeping upstairs. We heard a terrible thump-thump-thump-thump outside. A U.S. Army helicopter was circling the compound perhaps 200 feet off the ground. A soldier was strapped in the open side door taking pictures of the compound.

Karen said, “I know how to get them to come closer.” She went out on the roof and slowly took off her blouse, showing the soldier with the camera what it was he was fighting to protect. The chopper came down so close I could almost read the soldier’s name tag on his shirt.

Then Karen reached into the window of Paul’s bedroom next to the roof and pulled out an M-1 automatic rifle. I didn’t know he had a weapon. She fired off a dozen rounds at the chopper. They pulled away as fast as they could.

Cool as can be, she said, “If they’re gonna treat us like the enemy then I guess this is a combat situation.”

“What the hell!” I said. “Now the cops are gonna show up, big time!”

“Doubt it,” she said. “They’d have to explain what an Army chopper was doing harassing American citizens in the middle of a fig orchard.”

She was right.

On May 4, 1970, four students were murdered by the National Guard at Kent State University and two were killed by state troopers at Jackson State in Mississippi. Two days later, more than 800 universities went on spontaneous strikes across the country.

A few thousand of us marched off the Fresno State campus to Shaw Avenue and shut it down. From the crowd of thousands, the cops charged in and handpicked the leaders recognized from their surveillance photos. Forty-seven of us were busted, most on misdemeanor charges.

I was treated to two felony counts of possession of a deadly weapon: a pair of round-nosed bandage scissors in a Walgreens first-aid kit and a carabineer used to hold my crash helmet to my belt in case of a cop-riot.

I did a week in jail and was blackballed from a long list of jobs. However, there was a silver lining. I was also issued a special 1-W deferment by the draft board, not to be taken into the Army unless we were invaded. My lawyer said they only do that if they’re afraid you’ll become an organizer in the Army.

When the war was finally over in 1974, we expected to return to ordinary life, get jobs and blend in. I discovered this was not possible.

Just like the soldiers who had fought for their country overseas, we had set aside the pursuit of self-directed careers and fought for a vision of a future at home. In 1978, I discovered I was still disoriented, suffering from a delayed case of something like combat stress disorder.

I and my brothers and sisters in this struggle would never return to take up a “normal” life. Almost all of us continued to stay active in politics raising hell one way or another to this day.

There is an old Russian revolutionary proverb: “Do you know how to make a Thief’s Omelet?”

“First, you must steal two eggs.”

No one else is going to do this for you. Your time will come.

*****

Joel D. Eis began life as a “Red Diaper Baby” in a leftist family. After participating in the Student Strike of 1968 at San Francisco State, he became a Conscientious Objector to the draft and a member of El Teatro Campesino, while organizing again the war in Fresno and San Jose. After spending 45 years as theatre teacher and professional designer, he now owns and operates the Rebound Bookstore in San Rafael with his stunning wife, Toni.

Add Your Comments

Comments

(Hide Comments)

"The war fell upon the bodies of working-class young men and women..."

Really? How many women were in combat roles in Vietnam?

Really? How many women were in combat roles in Vietnam?

Over a million. They were Vietnamese, Cambodian, etc.

We are 100% volunteer and depend on your participation to sustain our efforts!

Get Involved

If you'd like to help with maintaining or developing the website, contact us.

Publish

Publish your stories and upcoming events on Indybay.

Topics

More

Search Indybay's Archives

Advanced Search

►

▼

IMC Network