From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

SF Forum "Lessons and Relevance Of The Russian Revolution For Today" With Screening

Date:

Sunday, November 12, 2017

Time:

1:00 PM

-

4:00 PM

Event Type:

Class/Workshop

Organizer/Author:

UPWA

Location Details:

San Francisco Main Public Library

100 Larkin St. Latino Room Lower Level

San Francisco

100 Larkin St. Latino Room Lower Level

San Francisco

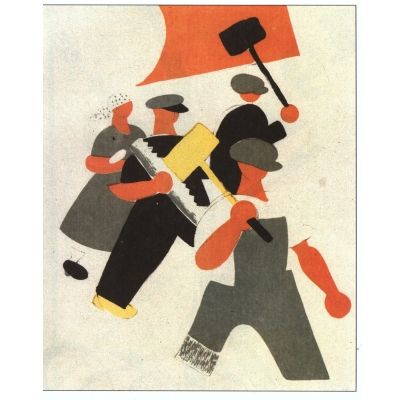

Lessons and Relevance Of The Russian Revolution For Today & Screening of “From The Czar To Lenin"

Sunday November 12, 2017 1:00 PM

San Francisco Main Public Library

100 Larkin St. Latino Room Lower Level

San Francisco

One hundred years ago, the working class through the Soviets took power in Russia. The revolution had reverberations throughout the world including in the US, California and the bay area. While the Democratic party politicians today are wailing about the role of Putin and Russia, the US government actually invaded Russia with 20 other countries in 1919 to overthrow the new government. Longshore workers in Seattle also stopped the loading of rifles to Russia.

At the same time, a battle was going on within the labor movement in the US about what position the unions should take to the revolution and US capitalism. US workers today are under attack as the capitalists seek to privatize education along with all public services and destroy our unions while moving toward world war. The decline of US capitalism is also directly leading to the rise of Trump and other forces.

As the US hurtles toward world war today and growing fascist forces, the question of the relevancy and lessons of the Russian revolution is important for today.

This forum will also look at how the Russian revolution impacted working people in the US and California.

Agenda:

Screening of “From The Czar To Lenin”

Presentations:

George Wright, Russia,Trump, The Decline Of US Imperialism And The Danger of World War

Jack Heyman, Retired ILWU Local 10, Chair Transport Workers Solidarity Committee on US Workers And The Tasks Today

John Holmes, The Russian Revolution And It’s Impact On The Working Class and Unions In California

Steve Zeltzer, How Workers And Unions Need To Defend Their Gains and Go On The Offensive

Sponsored by

KPFA WorkWeek Radio

United Public Workers For Action

http://www.upwa.info

info(at)upwa.info

Sunday November 12, 2017 1:00 PM

San Francisco Main Public Library

100 Larkin St. Latino Room Lower Level

San Francisco

One hundred years ago, the working class through the Soviets took power in Russia. The revolution had reverberations throughout the world including in the US, California and the bay area. While the Democratic party politicians today are wailing about the role of Putin and Russia, the US government actually invaded Russia with 20 other countries in 1919 to overthrow the new government. Longshore workers in Seattle also stopped the loading of rifles to Russia.

At the same time, a battle was going on within the labor movement in the US about what position the unions should take to the revolution and US capitalism. US workers today are under attack as the capitalists seek to privatize education along with all public services and destroy our unions while moving toward world war. The decline of US capitalism is also directly leading to the rise of Trump and other forces.

As the US hurtles toward world war today and growing fascist forces, the question of the relevancy and lessons of the Russian revolution is important for today.

This forum will also look at how the Russian revolution impacted working people in the US and California.

Agenda:

Screening of “From The Czar To Lenin”

Presentations:

George Wright, Russia,Trump, The Decline Of US Imperialism And The Danger of World War

Jack Heyman, Retired ILWU Local 10, Chair Transport Workers Solidarity Committee on US Workers And The Tasks Today

John Holmes, The Russian Revolution And It’s Impact On The Working Class and Unions In California

Steve Zeltzer, How Workers And Unions Need To Defend Their Gains and Go On The Offensive

Sponsored by

KPFA WorkWeek Radio

United Public Workers For Action

http://www.upwa.info

info(at)upwa.info

For more information:

http://www.upwa.info

Added to the calendar on Fri, Oct 13, 2017 11:01PM

Add Your Comments

Comments

(Hide Comments)

100 years later, Bolshevism is back. And we should be worried.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/global-opinions/bolshevism-then-and-now/2017/11/06/830aecaa-bf41-11e7-959c-fe2b598d8c00_story.html?hpid=hp_no-name_opinion-card-f%3Ahomepage%2Fstory&utm_term=.cb82189703fa

By Anne Applebaum Columnist November 6 at 11:24 AM

Communist Party supporters with red flags and a flag with a portrait of Vladimir Lenin walk during a demonstration marking the 100th anniversary of the 1917 Bolshevik revolution in Moscow’s Red Square on Nov. 5. (Alexander Zemlianichenko/AP)

At the beginning of 1917, on the eve of the Russian revolution, most of the men who would become known to the world as the Bolsheviks had very little to show for their lives. They had been in and out of prison, constantly under police surveillance, rarely employed. Vladimir Lenin spent most of the decade preceding the revolution drifting between Krakow, Zurich and London. Joseph Stalin spent those years in the Caucasus, running protection rackets and robbing banks. Leon Trotsky had escaped from Siberian exile was to be found in Viennese coffee shops; when the revolution broke out, he was showing off his glittering brilliance at socialist meeting halls in New York.

They were peripheral figures even in the Russian revolutionary underground. Trotksy had played a small role in the unsuccessful revolution of 1905 — the bloody, spontaneous uprising that the historian Richard Pipes has called “the foreshock” — but Lenin was abroad. None of them played a major role in the February revolution, the first of the two revolutions of 1917, when hungry workers and mutinous soldiers occupied the streets of Petrograd, as St. Petersburg was then called, and forced the czar to abdicate. Alexander Shliapnikov, one of the few Bolsheviks to reach the Russian capital at the time, even dismissed the February street protests, at first, as inconsequential: “What revolution? Give the workers a pound of bread and the movement will peter out.” Chaotic elections to the first workers’ soviet, a kind of spontaneous council, were held a few days before the czar’s abdication; the Bolsheviks got only a fraction of the vote. At that moment, Alexander Kerensky, who was to become the Provisional Government’s liberal leader, enjoyed widespread support.

Seven months later the Bolsheviks were in charge. A Russian friend of mine likes to say, in the spirit of Voltaire’s famous joke about the Holy Roman Empire, that the Great October Revolution, as it was always known in Soviet days, was none of those things: not great (it was an economic and political disaster); not in October (according to the Gregorian calendar it was actually Nov. 7); and, above all, not a revolution. It was a Bolshevik coup d’etat. But it was not an accident, either. Lenin began plotting a violent seizure of power before he had even learned of the czar’s abdication. Immediately — “within a few hours,” according to Victor Sebestyen’s excellent new biography, “Lenin: The Man, the Dictator, and the Master of Terror” — he sent out a list of orders to his colleagues in Petrograd. They included “no trust or support for the new government,” “arm the proletariat” and “make no rapprochement of any kind with other parties.” More than a thousand miles away, in Switzerland, he could not possibly have had any idea what the new government stood for. But as a man who had spent much of the previous 20 years fighting against “bourgeois democracy,” and arguing virulently against elections and parties, he already knew that he wanted it smashed.

His extremism was precisely what persuaded the German government, then at war with Russia, to help Lenin carry out his plans. “We must now definitely try to create the utmost chaos in Russia,” one German official advised. “We must secretly do all that we can to aggravate the differences between the moderate and the extreme parties . . . since we are interested in the victory of the latter.” The kaiser personally approved of the idea; his generals hoped it would lead the Russian state to collapse and withdraw from the war. And so the German government promised Lenin funding, put him and 30 other Bolsheviks — among them his wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya , as well as his mistress, Inessa Armand — onto a train, and sent them to revolutionary Petrograd. They arrived at the Finland Station on April 16, where they were welcomed by a cheering crowd.

[Red century: The rise and decline of global communism]

A few days later Lenin issued his famous April Theses, which echoed the orders that he had sent from Zurich. He treated the Bolsheviks’ minority status as temporary, the product of a misunderstanding: “It must be explained to the masses that the Soviet of Workers’ Deputies is the only possible form of revolutionary government.” He showed his scorn for democracy, dismissing the idea of a parliamentary republic as “a retrograde step.” He called for the abolition of the police, the army and the bureaucracy, as well as the nationalization of all land and all banks.

Plenty of people thought he was crazy. But in the weeks that followed, Lenin stuck to his extremist vision despite the objections of his more moderate colleagues, agitating for it all over the city. Using a formula that would be imitated and repeated by demagogues around the world for decades to come — up to and including the demagogues of the present, about which more in a moment — he and the other Bolsheviks offered poor people simplistic answers to complex questions. They called for “peace, land and bread.” They sketched out beautiful pictures of an impossible future. They promised not only wealth but also happiness, a better life in a better nation.

Trotsky later wrote with an almost mystical lyricism about this period, a time when “meetings were held in plants, schools and colleges, in theatres, circuses, streets and squares.” His favorite events took place at the Petrograd Circus:

“I usually spoke in the Circus in the evening, sometimes quite late at night. My audience was composed of workers, soldiers, hard-working mothers, street urchins—the oppressed under-dogs of the capital. Every square inch was filled, every human body compressed to its limit. Young boys sat on their fathers’ shoulders; infants were at their mothers’ breasts. No one smoked. The balconies threatened to fall under the excessive weight of human bodies. I made my way to the platform through a narrow human trench, sometimes I was borne overhead. The air, intense with breathing and waiting, fairly exploded with shouts. . . .

“No speaker, no matter how exhausted, could resist the electric tension of that impassioned human throng. They wanted to know, to understand, to find their way. At times it seemed as if I felt, with my lips, the stern inquisitiveness of this crowd that had become merged into a single whole. Then all the arguments and words thought out in advance would break and recede under the imperative pressure of sympathy, and other words, other arguments, utterly unexpected by the orator but needed by these people, would emerge in full array from my subconsciousness.”

This feeling of oneness with the masses — the sensation, bizarrely narcissistic, that he was the authentic Voice of the People, the living embodiment of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat — supported Trotsky and propelled him onward. It also disguised the fact that, like Lenin, he was lying.

Power in chaos

So were all his comrades. The Bolsheviks lied about the past — the relationships some of them had with the czarist police, Lenin’s secret pact with Germany — and they lied about the future, too. All through the spring and summer of 1917, Trotsky and Lenin repeatedly made promises that would never be kept. “Peace, Land, and Bread”? Their offer of “peace” concealed their faith in the coming world revolution and their determination to use force to bring it about. Their offer of “land” disguised a plan to keep all property in state hands. Their offer of “bread” concealed an ideological obsession with centralized food production that would keep Russians hungry or decades.

But in 1917, the fairy tales told by Lenin, Trotsky, and the others won the day. They certainly did not persuade all Russians, or even a majority of the Russians, to support them. They did not persuade the Petrograd Soviet or the other socialist parties. But they did persuade a fanatical and devoted minority, one that would kill for the cause. And in the political chaos that followed the czar’s abdication, in a city that was paralyzed by food shortages, distracted by rumors and haunted by an unpopular war, a fanatical and devoted minority proved sufficient.

Capturing power was not difficult. Using the tactics of psychological warfare that would later become their trademark, the Bolsheviks convinced a mob of supporters that they were under attack, and directed them to sack the Winter Palace, where the ministers of the Provisional Government were meeting. As Stalin later remembered, the party leadership “disguised its offensive actions behind a smoke screen of defenses.” They lied again, in other words, to inspire their fanatical followers to fight. After a brief scuffle — the ministers put up no real defense — Lenin, without any endorsement from any institution other than his own party, declared himself the leader of a country that he renamed Soviet Russia.

Keeping power was much harder. Precisely because he represented a fanatical minority and had been endorsed by no one else, Lenin’s proclamation was only the beginning of what would become a long and bloody struggle. Socialists in other countries used the Marxist expression “class war” as a metaphor; they meant only class rivalry, perhaps conducted through the ballot box, or at most a bit of street fighting. But from the beginning, the Bolsheviks always envisioned actual class warfare, accompanied by actual mass violence, which would physically destroy the aristocracy and the bourgeoisie, physically destroy their shops and factories, physically destroy the schools, the courts, the press. In October 1917, they began using that mass violence. In the subsequent Russian and Ukrainian civil wars that consumed the former empire between 1918 and 1921, hundreds of thousands of people died. Millions more would die in waves of terror in the years that followed.

In this photo taken in October 1917, members of the revolution Red Guards pose for a photo with their arms at the Smolny Institute building, which was chosen by Vladimir Lenin as Bolshevik headquarters during the October Revolution in 1917. ((Russian State Archive of Social and Political History via AP)

The chaos was vast. But many in Russia came to embrace the destruction. They argued that the “system” was so corrupt, so immune to reform or repair, that it had to be smashed. Some welcomed the bonfire of civilization with something bordering on ecstasy. The beauty of violence, the cleansing power of violence: these were themes that inspired Russian poetry and prose in 1918. Krasnaya Gazeta, the newspaper of the Red Army, urged the soldiers of the Bolshevik cause to be merciless to their enemies: “Let them be thousands, let them drown themselves in their own blood . . . let there be floods of blood of the bourgeoisie — more blood, as much as possible.” A young Ukrainian named Vsevolod Balytsky, one of the early members of the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police, published a poem in the Ukrainian edition of Izvestiya in 1919:

There, where even yesterday life was so joyous

Flows the river of blood

And so? There where it flows

There will be no mercy

Nothing will save you, nothing!

Fourteen years later, Balytsky, by then the secret police boss in Ukraine, would launch the mass arrests and searches that culminated in the Ukrainian famine, an artificially created catastrophe that killed nearly four million people. Four years after that, in 1937, Balytsky was himself executed by a firing squad.

Also in that year, the peak year of the Great Terror, Stalin eliminated anyone in the country whom he suspected might have dissenting views of any kind. Lenin had already eliminated the other socialist parties. Stalin focused on the “enemies” inside his own party, both real and imaginary, in a bloody mass purge. Like Lenin, Stalin never accepted any form of legal opposition — indeed he never believed that there could be such a thing as constructive opposition at all. Truth was defined by the leader. The direction of state policy was defined by the leader. Everyone and everything that opposed the leader — parties, courts, media — was an “enemy of the people,” a phrase that Lenin stole from the French Revolution.

Within two decades of October 1917, the Revolution had devoured not only its children, but also its founders — the men and women who had been motivated by such passion for destruction. It created not a beautiful new civilization but an angry, unhappy, and embittered society, one that squandered its resources, built ugly, inhuman cities, and broke new ground in atrocity and mass murder. Even as the Soviet Union became less violent, in the years following Stalin’s death in 1953, it remained dishonest and intolerant, insisting on a facade of unity. As the philosopher Roger Scruton has observed, Bolshevism eventually became so cocooned in layers of dishonesty that it lost touch with reality: “Facts no longer made contact with the theory, which had risen above the facts on clouds of nonsense, rather like a theological system. The point was not to believe the theory, but to repeat it ritualistically and in such a way that both belief and doubt became irrelevant. . . . In this way the concept of truth disappeared from the intellectual landscape, and was replaced by that of power.” Once people were unable to distinguish truth from ideological fiction, however, they were also unable to solve or even describe the worsening social and economic problems of their society. Fear, hatred, cynicism and criminality were all around them, with no obvious solutions in sight.

So discredited was Bolshevism after the Soviet Union’s demise in 1991 that, for a quarter of a century, it seemed as if Bolshevik thinking was gone for good. But suddenly, now, in the year of the revolution’s centenary, it’s back.

The neo-Bolsheviks

History repeats itself and so do ideas, but never in exactly the same way. Bolshevik thinking in 2017 does not sound exactly the way it sounded in 1917. There are, it is true, still a few Marxists around. In Spain and Greece they have formed powerful political parties, though in Spain they have yet to win power and in Greece they have been forced by the realities of international markets, to quietly drop their “revolutionary” agenda. The current leader of the British Labour Party, Jeremy Corbyn, also comes out of the old pro-Soviet far left. He has voiced anti-American, anti-NATO, anti-Israel, and even anti-British (and pro-IRA) sentiments for decades — predictable views that no longer sound shocking to a generation that cannot remember who sponsored them in the past. Within his party there is a core of radicals who speak of overthrowing capitalism and bringing back nationalization.

In the United States, the Marxist left has also consolidated on the fringes of the Democratic Party — and sometimes not even on the fringes — as well as on campuses, where it polices the speech of its members, fights to prevent students from hearing opposing viewpoints, and teaches a dark, negative version of American history, one calculated to create doubts about democracy and to cast shadows on all political debate. The followers of this new alt-left spurn basic patriotism and support America’s opponents, whether in Russia or the Middle East. As in Britain, they don’t remember the antecedents of their ideas and they don’t make a connection between their language and the words used by fanatics of a different era.

But so far, the new left, however fashionable it may be in some circles, is not in power, and thus has not managed to create a real revolution. In truth, the most influential contemporary Bolsheviks — the people who began, like Lenin and Trotsky, on the extremist fringes of political life and who are now in positions of power and real influence in several Western countries — come from a different political tradition altogether.

Marine Le Pen, head of France’s far-right National Front party, at an Oct. 22 news conference. (Fred Tanneau/AFP via Getty Images)

<2017-10-23T140658Z_679068073_UP1EDAN137LW0_RTRMADP_3_HUNGARY-POLITICS.jpg>

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban applauds after an Oct. 23 speech during the celebrations of 61th anniversary of the Hungarian Uprising of 1956. (Laszlo Balogh/Reuters)

Donald Trump, Viktor Orban, Nigel Farage, Marine Le Pen and Jaroslaw Kaczynski: although they are often described as “far-right” or “alt-right,” these neo-Bolsheviks have little to do with the right that has been part of Western politics since World War II, and they have no connection to existing conservative parties. In continental Europe, they scorn Christian Democracy, which had its political base in the church and sought to bring morality back to politics after the nightmare of the Second World War. Nor do they have anything to do with Anglo-Saxon conservatism, which promoted free markets, free speech and a Burkean small-c conservatism: skepticism of “progress,” suspicion of radicalism in all its forms, and a belief in the importance of conserving institutions and values. Whether German or Dutch Christian Democrats, British Tories, American Republicans, East European ex-dissidents or French Gaullists, post-war Western conservatives have all been dedicated to representative democracy, religious tolerance, economic integration and the Western alliance.

By contrast, the neo-Bolsheviks of the new right or alt-right do not want to conserve or to preserve what exists. They are not Burkeans but radicals who want to overthrow existing institutions. Instead of the false and misleading vision of the future offered by Lenin and Trotsky, they offer a false and misleading vision of the past. They conjure up worlds made up of ethnically or racially pure nations, old-fashioned factories, traditional male-female hierarchies and impenetrable borders. Their enemies are homosexuals, racial and religious minorities, advocates of human rights, the media, and the courts. They are often not real Christians but rather cynics who use “Christianity” as a tribal identifier, a way of distinguishing themselves from their enemies: they are “Christians” fighting against “Muslims” — or against “liberals” if there are no “Muslims” available.

To an extraordinary degree, they have adopted Lenin’s refusal to compromise, his anti-democratic elevation of some social groups over others and his hateful attacks on his “illegitimate” opponents. Law and Justice, the illiberal nationalist ruling party in Poland, has sorted its compatriots into “true Poles” and “Poles of the worst sort.” Trump speaks of “real” Americans, as opposed to the “elite.” Stephen Miller, a Trump acolyte and speechwriter, recently used the word “cosmopolitan,” an old Stalinist moniker for Jews (the full term was “rootless cosmopolitan”), to describe a reporter asking him tough questions. “Real” Americans are worth talking to; “cosmopolitans” need to be eliminated from public life.

Surprisingly, given its mild and pragmatic traditions, even British politics is now saturated with Leninist language. When British judges declared, in November 2016, that the Brexit referendum had to be confirmed by Parliament — a reasonable decision in a parliamentary democracy — the Daily Mail, a xenophobic pro-Brexit newspaper, ran a cover story with judges’ photographs and the phrase “Enemies of the People.” Later, the same paper called on the prime minister to “Crush the Saboteurs,” choosing a word that was also favored by Lenin to describe legitimate political opposition.

Famously, Trump has also used the expression “enemy of the American people” on Twitter. Though it is unlikely that the president himself understood the historical context, some of the people around him certainly did. Bannon, Miller and several others in Trump’s immediate orbit know perfectly well that the delegitimization of political opponents as “un-American” and “elitist,” and of the media as “fake news,” is the first step in a more ambitious direction. If some of what these extremists say is to be taken seriously, their endgame — the destruction of the existing political order, possibly including the U.S. Constitution — is one that the Bolsheviks would have understood. The historian Ronald Radosh has quoted Bannon’s comparison of himself to the Bolshevik leader. “Lenin,” Bannon told Radosh, “wanted to destroy the state, and that’s my goal too. I want to bring everything crashing down, and destroy all of today’s establishment.” At a conservative gathering in Washington in 2013, Bannon also called fora “virulently anti-establishment” and “insurgent” movement that will “hammer this city, both the progressive left and the institutional Republican Party.”

<_MFC4922-001.JPG>

A view of the crowd at the U.S. Capitol during President Trump’s inauguration on Jan. 20. (Bill O'Leary /The Washington Post)

And what gives a president who did not win the popular vote the right to do that? This, too, is a familiar idea: the “People.” It is a mystical notion, quite different from the actually existing population of America, but strikingly similar to the “crowd” in whose name Trotsky spoke at the Petrograd Circus. In his dark, nihilistic inaugural address, much of it written by Bannon and Miller, the president announced that he was “transferring power from Washington D.C. and giving it back to you, the American People” — as if the capital city had until 2017 somehow belonged to foreign occupiers. This un-American idea of the “People” bears more than a passing resemblance to the Dictatorship of the Proletariat, the force that scientific Marxism once predicted would run the world. It also sounds a lot like what Le Pen means by “the Nation,” as opposed to the “globalist elite,” or what the Law and Justice party in Poland mean when they talk about “suweren,” the sovereign nation, as opposed to the majority of Polish voters, who actually oppose them.

A nihilistic desire for disaster

Like their predecessors, the neo-Bolsheviks are also liars. Trump lies with pathological intensity about matters small and large, and he lies so often and so obviously that it is not even necessary to cite his uncounted falsehoods again here. But he is not alone. Recently Le Pen was charged in an investigation into her anti-European party for cheating the European parliament out of money. The Law and Justice party pretends that its attacks on the Polish constitution are nothing more than “judicial reform.” Orban has hidden the probably corrupt details of Russian investment in a nuclear plant in Hungary. These are not coincidences. Nor is it a coincidence that the most successful neo-Bolsheviks have all created their own “alternative media,” starting online and moving into the mainstream, specializing in disinformation, hate campaigns, racist jokes and organized trolling of opponents. (The old Bolsheviks used to call this propaganda, and they were brilliant at it.) Both the politicians and the “journalists” lie out of conviction, because they believe that ordinary morality does not apply to them. In a rotten world, truth can be sacrificed in the name of “the People,” or as a means of targeting “Enemies of the People.” In the struggle for power, anything is permitted.

Finally, and most painfully, there is a hint, and sometimes more than a hint, of a reviving appreciation among the neo-Bolsheviks for the cleansing possibilities of violence. The violent poetry of 1917 has morphed into the violent memes of 2017, the “Ultra Violence” threads on Reddit, the white nationalist groups seeking “race war,” and the NRA videos urging Americans to arm themselves for the coming apocalyptic struggle to “save our country.” Some of this dangerous trash has been around for a long time: far-right and far-left extremists in Europe have always savored the idea of violence. But now some of that nihilistic desire for disaster has become mainstream, even reaching the White House. As long ago as 2014, Trump, after railing against Obamacare, fantasized: “You know what solves it? When the economy crashes, when the country goes to total hell and everything is a disaster. Then you’ll have a, you know, you’ll have riots to go back to where we used to be when we were great.”

Shocking though it is, that sentiment is mild by comparison with Bannon’s apocalyptic vision of a coming war — perhaps with Islam, perhaps with China — that will cleanse the Western world of weakness and restore Western greatness. This is how Bannon put it in 2010: “We’re gonna have to have some dark days before we get to the blue sky of morning again in America. We are going to have to take some massive pain. Anybody who thinks we don’t have to take pain is, I believe, fooling you.” A HuffPost article included similar Bannon statements. In 2011: “Against radical Islam, we’re in a 100-year war.” In 2014: “We are in an outright war against jihadist Islamic fascism. And this war is, I think, metastasizing far quicker than governments can handle it.” In 2016: “We’re going to war in the South China Seas in the next five to ten years, aren’t we?”

An echo of this lust for war can also be heard in the schizophrenic speech on “Western civilization” that Bannon is said to have helped write for Trump in Warsaw in July. Amid some paragraphs that sounded almost like a normal foreign policy speech, someone inserted a passage describing the Warsaw uprising — a horrific and destructive battle which, despite great courage, the Polish resistance army lost. Those heroes,” Trump declared, “remind us that the West was saved with the blood of patriots; that each generation must rise up and play their part in its defense.” Each generation? That means our generation, too: Get your weapons ready, because these people want you and your children to bleed and die in the cause of civilizational renewal.

No excuse for complacency

Fortunately, we do not live in 1917 Petrograd. There are no bread shortages, or ragged barefoot soldiers, or aristocrats in thrall to mad monks. There will be few opportunities to surround the government in a palace, enter and take it over. Our states are not, yet, that weak.

We also have, as the Russians of 1917 did not have, the benefit of hindsight. In much of continental Europe, the demagogue who divides the nation into enemies and patriots creates bad connotations and triggers unpleasant memories. Over the past year, French, Dutch and Austrian voters rejected the nihilism and xenophobia of Le Pen, Geert Wilders and Norbert Hofer, not least because of what they resembled.

The French may even have taken the first necessary step in the longer battle against false revolutions by voting for Emmanuel Macron, the first major European politician to argue for a muscular revival of liberalism. Macron openly opposed the fear, the nostalgia and the nativism on the rise across the continent, and he won without offering impossible schemes or unattainable riches. Even if he fails in France, his formula hints at a way to fight back against modern false prophets. Offer a positive vision, both open and patriotic. Don’t let the nationalists appeal to “the People” over the heads of the voters. Don’t let extremists become mainstream.

But the Anglo-Saxon world was less lucky. It may not be an accident that neo-Bolshevik language has so far enjoyed unprecedented success in Britain and the United States, two countries that have never known the horror of occupation or of an undemocratic revolution that ended in dictatorship. They therefore lack the immunity of many Europeans. On the other hand, the Anglo-Saxon world has its own advantages: the bonds of old and long-standing constitutionalism, the habits created by decades of rule of law and relatively high standards of living. It may be that as Americans and Brits slowly learn to recognize lies, they will become less susceptible to the fake nostalgia on offer from their leaders.

But there is no excuse for complacency. That is the lesson of this ominous centennial. Remember: At the beginning of 1917, on the eve of the Russian revolution, most of the men who later became known to the world as the Bolsheviks were conspirators and fantasists on the margins of society. By the end of the year, they ran Russia. Fringe figures and eccentric movements cannot be counted out. If a system becomes weak enough and the opposition divided enough, if the ruling order is corrupt enough and people are angry enough, extremists can suddenly step into the center, where no one expects them. And after that it can take decades to undo the damage. We have been shocked too many times. Our imaginations need to expand to include the possibilities of such monsters and monstrosities. We were not adequately prepared.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/global-opinions/bolshevism-then-and-now/2017/11/06/830aecaa-bf41-11e7-959c-fe2b598d8c00_story.html?hpid=hp_no-name_opinion-card-f%3Ahomepage%2Fstory&utm_term=.cb82189703fa

By Anne Applebaum Columnist November 6 at 11:24 AM

Communist Party supporters with red flags and a flag with a portrait of Vladimir Lenin walk during a demonstration marking the 100th anniversary of the 1917 Bolshevik revolution in Moscow’s Red Square on Nov. 5. (Alexander Zemlianichenko/AP)

At the beginning of 1917, on the eve of the Russian revolution, most of the men who would become known to the world as the Bolsheviks had very little to show for their lives. They had been in and out of prison, constantly under police surveillance, rarely employed. Vladimir Lenin spent most of the decade preceding the revolution drifting between Krakow, Zurich and London. Joseph Stalin spent those years in the Caucasus, running protection rackets and robbing banks. Leon Trotsky had escaped from Siberian exile was to be found in Viennese coffee shops; when the revolution broke out, he was showing off his glittering brilliance at socialist meeting halls in New York.

They were peripheral figures even in the Russian revolutionary underground. Trotksy had played a small role in the unsuccessful revolution of 1905 — the bloody, spontaneous uprising that the historian Richard Pipes has called “the foreshock” — but Lenin was abroad. None of them played a major role in the February revolution, the first of the two revolutions of 1917, when hungry workers and mutinous soldiers occupied the streets of Petrograd, as St. Petersburg was then called, and forced the czar to abdicate. Alexander Shliapnikov, one of the few Bolsheviks to reach the Russian capital at the time, even dismissed the February street protests, at first, as inconsequential: “What revolution? Give the workers a pound of bread and the movement will peter out.” Chaotic elections to the first workers’ soviet, a kind of spontaneous council, were held a few days before the czar’s abdication; the Bolsheviks got only a fraction of the vote. At that moment, Alexander Kerensky, who was to become the Provisional Government’s liberal leader, enjoyed widespread support.

Seven months later the Bolsheviks were in charge. A Russian friend of mine likes to say, in the spirit of Voltaire’s famous joke about the Holy Roman Empire, that the Great October Revolution, as it was always known in Soviet days, was none of those things: not great (it was an economic and political disaster); not in October (according to the Gregorian calendar it was actually Nov. 7); and, above all, not a revolution. It was a Bolshevik coup d’etat. But it was not an accident, either. Lenin began plotting a violent seizure of power before he had even learned of the czar’s abdication. Immediately — “within a few hours,” according to Victor Sebestyen’s excellent new biography, “Lenin: The Man, the Dictator, and the Master of Terror” — he sent out a list of orders to his colleagues in Petrograd. They included “no trust or support for the new government,” “arm the proletariat” and “make no rapprochement of any kind with other parties.” More than a thousand miles away, in Switzerland, he could not possibly have had any idea what the new government stood for. But as a man who had spent much of the previous 20 years fighting against “bourgeois democracy,” and arguing virulently against elections and parties, he already knew that he wanted it smashed.

His extremism was precisely what persuaded the German government, then at war with Russia, to help Lenin carry out his plans. “We must now definitely try to create the utmost chaos in Russia,” one German official advised. “We must secretly do all that we can to aggravate the differences between the moderate and the extreme parties . . . since we are interested in the victory of the latter.” The kaiser personally approved of the idea; his generals hoped it would lead the Russian state to collapse and withdraw from the war. And so the German government promised Lenin funding, put him and 30 other Bolsheviks — among them his wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya , as well as his mistress, Inessa Armand — onto a train, and sent them to revolutionary Petrograd. They arrived at the Finland Station on April 16, where they were welcomed by a cheering crowd.

[Red century: The rise and decline of global communism]

A few days later Lenin issued his famous April Theses, which echoed the orders that he had sent from Zurich. He treated the Bolsheviks’ minority status as temporary, the product of a misunderstanding: “It must be explained to the masses that the Soviet of Workers’ Deputies is the only possible form of revolutionary government.” He showed his scorn for democracy, dismissing the idea of a parliamentary republic as “a retrograde step.” He called for the abolition of the police, the army and the bureaucracy, as well as the nationalization of all land and all banks.

Plenty of people thought he was crazy. But in the weeks that followed, Lenin stuck to his extremist vision despite the objections of his more moderate colleagues, agitating for it all over the city. Using a formula that would be imitated and repeated by demagogues around the world for decades to come — up to and including the demagogues of the present, about which more in a moment — he and the other Bolsheviks offered poor people simplistic answers to complex questions. They called for “peace, land and bread.” They sketched out beautiful pictures of an impossible future. They promised not only wealth but also happiness, a better life in a better nation.

Trotsky later wrote with an almost mystical lyricism about this period, a time when “meetings were held in plants, schools and colleges, in theatres, circuses, streets and squares.” His favorite events took place at the Petrograd Circus:

“I usually spoke in the Circus in the evening, sometimes quite late at night. My audience was composed of workers, soldiers, hard-working mothers, street urchins—the oppressed under-dogs of the capital. Every square inch was filled, every human body compressed to its limit. Young boys sat on their fathers’ shoulders; infants were at their mothers’ breasts. No one smoked. The balconies threatened to fall under the excessive weight of human bodies. I made my way to the platform through a narrow human trench, sometimes I was borne overhead. The air, intense with breathing and waiting, fairly exploded with shouts. . . .

“No speaker, no matter how exhausted, could resist the electric tension of that impassioned human throng. They wanted to know, to understand, to find their way. At times it seemed as if I felt, with my lips, the stern inquisitiveness of this crowd that had become merged into a single whole. Then all the arguments and words thought out in advance would break and recede under the imperative pressure of sympathy, and other words, other arguments, utterly unexpected by the orator but needed by these people, would emerge in full array from my subconsciousness.”

This feeling of oneness with the masses — the sensation, bizarrely narcissistic, that he was the authentic Voice of the People, the living embodiment of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat — supported Trotsky and propelled him onward. It also disguised the fact that, like Lenin, he was lying.

Power in chaos

So were all his comrades. The Bolsheviks lied about the past — the relationships some of them had with the czarist police, Lenin’s secret pact with Germany — and they lied about the future, too. All through the spring and summer of 1917, Trotsky and Lenin repeatedly made promises that would never be kept. “Peace, Land, and Bread”? Their offer of “peace” concealed their faith in the coming world revolution and their determination to use force to bring it about. Their offer of “land” disguised a plan to keep all property in state hands. Their offer of “bread” concealed an ideological obsession with centralized food production that would keep Russians hungry or decades.

But in 1917, the fairy tales told by Lenin, Trotsky, and the others won the day. They certainly did not persuade all Russians, or even a majority of the Russians, to support them. They did not persuade the Petrograd Soviet or the other socialist parties. But they did persuade a fanatical and devoted minority, one that would kill for the cause. And in the political chaos that followed the czar’s abdication, in a city that was paralyzed by food shortages, distracted by rumors and haunted by an unpopular war, a fanatical and devoted minority proved sufficient.

Capturing power was not difficult. Using the tactics of psychological warfare that would later become their trademark, the Bolsheviks convinced a mob of supporters that they were under attack, and directed them to sack the Winter Palace, where the ministers of the Provisional Government were meeting. As Stalin later remembered, the party leadership “disguised its offensive actions behind a smoke screen of defenses.” They lied again, in other words, to inspire their fanatical followers to fight. After a brief scuffle — the ministers put up no real defense — Lenin, without any endorsement from any institution other than his own party, declared himself the leader of a country that he renamed Soviet Russia.

Keeping power was much harder. Precisely because he represented a fanatical minority and had been endorsed by no one else, Lenin’s proclamation was only the beginning of what would become a long and bloody struggle. Socialists in other countries used the Marxist expression “class war” as a metaphor; they meant only class rivalry, perhaps conducted through the ballot box, or at most a bit of street fighting. But from the beginning, the Bolsheviks always envisioned actual class warfare, accompanied by actual mass violence, which would physically destroy the aristocracy and the bourgeoisie, physically destroy their shops and factories, physically destroy the schools, the courts, the press. In October 1917, they began using that mass violence. In the subsequent Russian and Ukrainian civil wars that consumed the former empire between 1918 and 1921, hundreds of thousands of people died. Millions more would die in waves of terror in the years that followed.

In this photo taken in October 1917, members of the revolution Red Guards pose for a photo with their arms at the Smolny Institute building, which was chosen by Vladimir Lenin as Bolshevik headquarters during the October Revolution in 1917. ((Russian State Archive of Social and Political History via AP)

The chaos was vast. But many in Russia came to embrace the destruction. They argued that the “system” was so corrupt, so immune to reform or repair, that it had to be smashed. Some welcomed the bonfire of civilization with something bordering on ecstasy. The beauty of violence, the cleansing power of violence: these were themes that inspired Russian poetry and prose in 1918. Krasnaya Gazeta, the newspaper of the Red Army, urged the soldiers of the Bolshevik cause to be merciless to their enemies: “Let them be thousands, let them drown themselves in their own blood . . . let there be floods of blood of the bourgeoisie — more blood, as much as possible.” A young Ukrainian named Vsevolod Balytsky, one of the early members of the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police, published a poem in the Ukrainian edition of Izvestiya in 1919:

There, where even yesterday life was so joyous

Flows the river of blood

And so? There where it flows

There will be no mercy

Nothing will save you, nothing!

Fourteen years later, Balytsky, by then the secret police boss in Ukraine, would launch the mass arrests and searches that culminated in the Ukrainian famine, an artificially created catastrophe that killed nearly four million people. Four years after that, in 1937, Balytsky was himself executed by a firing squad.

Also in that year, the peak year of the Great Terror, Stalin eliminated anyone in the country whom he suspected might have dissenting views of any kind. Lenin had already eliminated the other socialist parties. Stalin focused on the “enemies” inside his own party, both real and imaginary, in a bloody mass purge. Like Lenin, Stalin never accepted any form of legal opposition — indeed he never believed that there could be such a thing as constructive opposition at all. Truth was defined by the leader. The direction of state policy was defined by the leader. Everyone and everything that opposed the leader — parties, courts, media — was an “enemy of the people,” a phrase that Lenin stole from the French Revolution.

Within two decades of October 1917, the Revolution had devoured not only its children, but also its founders — the men and women who had been motivated by such passion for destruction. It created not a beautiful new civilization but an angry, unhappy, and embittered society, one that squandered its resources, built ugly, inhuman cities, and broke new ground in atrocity and mass murder. Even as the Soviet Union became less violent, in the years following Stalin’s death in 1953, it remained dishonest and intolerant, insisting on a facade of unity. As the philosopher Roger Scruton has observed, Bolshevism eventually became so cocooned in layers of dishonesty that it lost touch with reality: “Facts no longer made contact with the theory, which had risen above the facts on clouds of nonsense, rather like a theological system. The point was not to believe the theory, but to repeat it ritualistically and in such a way that both belief and doubt became irrelevant. . . . In this way the concept of truth disappeared from the intellectual landscape, and was replaced by that of power.” Once people were unable to distinguish truth from ideological fiction, however, they were also unable to solve or even describe the worsening social and economic problems of their society. Fear, hatred, cynicism and criminality were all around them, with no obvious solutions in sight.

So discredited was Bolshevism after the Soviet Union’s demise in 1991 that, for a quarter of a century, it seemed as if Bolshevik thinking was gone for good. But suddenly, now, in the year of the revolution’s centenary, it’s back.

The neo-Bolsheviks

History repeats itself and so do ideas, but never in exactly the same way. Bolshevik thinking in 2017 does not sound exactly the way it sounded in 1917. There are, it is true, still a few Marxists around. In Spain and Greece they have formed powerful political parties, though in Spain they have yet to win power and in Greece they have been forced by the realities of international markets, to quietly drop their “revolutionary” agenda. The current leader of the British Labour Party, Jeremy Corbyn, also comes out of the old pro-Soviet far left. He has voiced anti-American, anti-NATO, anti-Israel, and even anti-British (and pro-IRA) sentiments for decades — predictable views that no longer sound shocking to a generation that cannot remember who sponsored them in the past. Within his party there is a core of radicals who speak of overthrowing capitalism and bringing back nationalization.

In the United States, the Marxist left has also consolidated on the fringes of the Democratic Party — and sometimes not even on the fringes — as well as on campuses, where it polices the speech of its members, fights to prevent students from hearing opposing viewpoints, and teaches a dark, negative version of American history, one calculated to create doubts about democracy and to cast shadows on all political debate. The followers of this new alt-left spurn basic patriotism and support America’s opponents, whether in Russia or the Middle East. As in Britain, they don’t remember the antecedents of their ideas and they don’t make a connection between their language and the words used by fanatics of a different era.

But so far, the new left, however fashionable it may be in some circles, is not in power, and thus has not managed to create a real revolution. In truth, the most influential contemporary Bolsheviks — the people who began, like Lenin and Trotsky, on the extremist fringes of political life and who are now in positions of power and real influence in several Western countries — come from a different political tradition altogether.

Marine Le Pen, head of France’s far-right National Front party, at an Oct. 22 news conference. (Fred Tanneau/AFP via Getty Images)

<2017-10-23T140658Z_679068073_UP1EDAN137LW0_RTRMADP_3_HUNGARY-POLITICS.jpg>

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban applauds after an Oct. 23 speech during the celebrations of 61th anniversary of the Hungarian Uprising of 1956. (Laszlo Balogh/Reuters)

Donald Trump, Viktor Orban, Nigel Farage, Marine Le Pen and Jaroslaw Kaczynski: although they are often described as “far-right” or “alt-right,” these neo-Bolsheviks have little to do with the right that has been part of Western politics since World War II, and they have no connection to existing conservative parties. In continental Europe, they scorn Christian Democracy, which had its political base in the church and sought to bring morality back to politics after the nightmare of the Second World War. Nor do they have anything to do with Anglo-Saxon conservatism, which promoted free markets, free speech and a Burkean small-c conservatism: skepticism of “progress,” suspicion of radicalism in all its forms, and a belief in the importance of conserving institutions and values. Whether German or Dutch Christian Democrats, British Tories, American Republicans, East European ex-dissidents or French Gaullists, post-war Western conservatives have all been dedicated to representative democracy, religious tolerance, economic integration and the Western alliance.

By contrast, the neo-Bolsheviks of the new right or alt-right do not want to conserve or to preserve what exists. They are not Burkeans but radicals who want to overthrow existing institutions. Instead of the false and misleading vision of the future offered by Lenin and Trotsky, they offer a false and misleading vision of the past. They conjure up worlds made up of ethnically or racially pure nations, old-fashioned factories, traditional male-female hierarchies and impenetrable borders. Their enemies are homosexuals, racial and religious minorities, advocates of human rights, the media, and the courts. They are often not real Christians but rather cynics who use “Christianity” as a tribal identifier, a way of distinguishing themselves from their enemies: they are “Christians” fighting against “Muslims” — or against “liberals” if there are no “Muslims” available.

To an extraordinary degree, they have adopted Lenin’s refusal to compromise, his anti-democratic elevation of some social groups over others and his hateful attacks on his “illegitimate” opponents. Law and Justice, the illiberal nationalist ruling party in Poland, has sorted its compatriots into “true Poles” and “Poles of the worst sort.” Trump speaks of “real” Americans, as opposed to the “elite.” Stephen Miller, a Trump acolyte and speechwriter, recently used the word “cosmopolitan,” an old Stalinist moniker for Jews (the full term was “rootless cosmopolitan”), to describe a reporter asking him tough questions. “Real” Americans are worth talking to; “cosmopolitans” need to be eliminated from public life.

Surprisingly, given its mild and pragmatic traditions, even British politics is now saturated with Leninist language. When British judges declared, in November 2016, that the Brexit referendum had to be confirmed by Parliament — a reasonable decision in a parliamentary democracy — the Daily Mail, a xenophobic pro-Brexit newspaper, ran a cover story with judges’ photographs and the phrase “Enemies of the People.” Later, the same paper called on the prime minister to “Crush the Saboteurs,” choosing a word that was also favored by Lenin to describe legitimate political opposition.

Famously, Trump has also used the expression “enemy of the American people” on Twitter. Though it is unlikely that the president himself understood the historical context, some of the people around him certainly did. Bannon, Miller and several others in Trump’s immediate orbit know perfectly well that the delegitimization of political opponents as “un-American” and “elitist,” and of the media as “fake news,” is the first step in a more ambitious direction. If some of what these extremists say is to be taken seriously, their endgame — the destruction of the existing political order, possibly including the U.S. Constitution — is one that the Bolsheviks would have understood. The historian Ronald Radosh has quoted Bannon’s comparison of himself to the Bolshevik leader. “Lenin,” Bannon told Radosh, “wanted to destroy the state, and that’s my goal too. I want to bring everything crashing down, and destroy all of today’s establishment.” At a conservative gathering in Washington in 2013, Bannon also called fora “virulently anti-establishment” and “insurgent” movement that will “hammer this city, both the progressive left and the institutional Republican Party.”

<_MFC4922-001.JPG>

A view of the crowd at the U.S. Capitol during President Trump’s inauguration on Jan. 20. (Bill O'Leary /The Washington Post)

And what gives a president who did not win the popular vote the right to do that? This, too, is a familiar idea: the “People.” It is a mystical notion, quite different from the actually existing population of America, but strikingly similar to the “crowd” in whose name Trotsky spoke at the Petrograd Circus. In his dark, nihilistic inaugural address, much of it written by Bannon and Miller, the president announced that he was “transferring power from Washington D.C. and giving it back to you, the American People” — as if the capital city had until 2017 somehow belonged to foreign occupiers. This un-American idea of the “People” bears more than a passing resemblance to the Dictatorship of the Proletariat, the force that scientific Marxism once predicted would run the world. It also sounds a lot like what Le Pen means by “the Nation,” as opposed to the “globalist elite,” or what the Law and Justice party in Poland mean when they talk about “suweren,” the sovereign nation, as opposed to the majority of Polish voters, who actually oppose them.

A nihilistic desire for disaster

Like their predecessors, the neo-Bolsheviks are also liars. Trump lies with pathological intensity about matters small and large, and he lies so often and so obviously that it is not even necessary to cite his uncounted falsehoods again here. But he is not alone. Recently Le Pen was charged in an investigation into her anti-European party for cheating the European parliament out of money. The Law and Justice party pretends that its attacks on the Polish constitution are nothing more than “judicial reform.” Orban has hidden the probably corrupt details of Russian investment in a nuclear plant in Hungary. These are not coincidences. Nor is it a coincidence that the most successful neo-Bolsheviks have all created their own “alternative media,” starting online and moving into the mainstream, specializing in disinformation, hate campaigns, racist jokes and organized trolling of opponents. (The old Bolsheviks used to call this propaganda, and they were brilliant at it.) Both the politicians and the “journalists” lie out of conviction, because they believe that ordinary morality does not apply to them. In a rotten world, truth can be sacrificed in the name of “the People,” or as a means of targeting “Enemies of the People.” In the struggle for power, anything is permitted.

Finally, and most painfully, there is a hint, and sometimes more than a hint, of a reviving appreciation among the neo-Bolsheviks for the cleansing possibilities of violence. The violent poetry of 1917 has morphed into the violent memes of 2017, the “Ultra Violence” threads on Reddit, the white nationalist groups seeking “race war,” and the NRA videos urging Americans to arm themselves for the coming apocalyptic struggle to “save our country.” Some of this dangerous trash has been around for a long time: far-right and far-left extremists in Europe have always savored the idea of violence. But now some of that nihilistic desire for disaster has become mainstream, even reaching the White House. As long ago as 2014, Trump, after railing against Obamacare, fantasized: “You know what solves it? When the economy crashes, when the country goes to total hell and everything is a disaster. Then you’ll have a, you know, you’ll have riots to go back to where we used to be when we were great.”

Shocking though it is, that sentiment is mild by comparison with Bannon’s apocalyptic vision of a coming war — perhaps with Islam, perhaps with China — that will cleanse the Western world of weakness and restore Western greatness. This is how Bannon put it in 2010: “We’re gonna have to have some dark days before we get to the blue sky of morning again in America. We are going to have to take some massive pain. Anybody who thinks we don’t have to take pain is, I believe, fooling you.” A HuffPost article included similar Bannon statements. In 2011: “Against radical Islam, we’re in a 100-year war.” In 2014: “We are in an outright war against jihadist Islamic fascism. And this war is, I think, metastasizing far quicker than governments can handle it.” In 2016: “We’re going to war in the South China Seas in the next five to ten years, aren’t we?”

An echo of this lust for war can also be heard in the schizophrenic speech on “Western civilization” that Bannon is said to have helped write for Trump in Warsaw in July. Amid some paragraphs that sounded almost like a normal foreign policy speech, someone inserted a passage describing the Warsaw uprising — a horrific and destructive battle which, despite great courage, the Polish resistance army lost. Those heroes,” Trump declared, “remind us that the West was saved with the blood of patriots; that each generation must rise up and play their part in its defense.” Each generation? That means our generation, too: Get your weapons ready, because these people want you and your children to bleed and die in the cause of civilizational renewal.

No excuse for complacency

Fortunately, we do not live in 1917 Petrograd. There are no bread shortages, or ragged barefoot soldiers, or aristocrats in thrall to mad monks. There will be few opportunities to surround the government in a palace, enter and take it over. Our states are not, yet, that weak.

We also have, as the Russians of 1917 did not have, the benefit of hindsight. In much of continental Europe, the demagogue who divides the nation into enemies and patriots creates bad connotations and triggers unpleasant memories. Over the past year, French, Dutch and Austrian voters rejected the nihilism and xenophobia of Le Pen, Geert Wilders and Norbert Hofer, not least because of what they resembled.

The French may even have taken the first necessary step in the longer battle against false revolutions by voting for Emmanuel Macron, the first major European politician to argue for a muscular revival of liberalism. Macron openly opposed the fear, the nostalgia and the nativism on the rise across the continent, and he won without offering impossible schemes or unattainable riches. Even if he fails in France, his formula hints at a way to fight back against modern false prophets. Offer a positive vision, both open and patriotic. Don’t let the nationalists appeal to “the People” over the heads of the voters. Don’t let extremists become mainstream.

But the Anglo-Saxon world was less lucky. It may not be an accident that neo-Bolshevik language has so far enjoyed unprecedented success in Britain and the United States, two countries that have never known the horror of occupation or of an undemocratic revolution that ended in dictatorship. They therefore lack the immunity of many Europeans. On the other hand, the Anglo-Saxon world has its own advantages: the bonds of old and long-standing constitutionalism, the habits created by decades of rule of law and relatively high standards of living. It may be that as Americans and Brits slowly learn to recognize lies, they will become less susceptible to the fake nostalgia on offer from their leaders.

But there is no excuse for complacency. That is the lesson of this ominous centennial. Remember: At the beginning of 1917, on the eve of the Russian revolution, most of the men who later became known to the world as the Bolsheviks were conspirators and fantasists on the margins of society. By the end of the year, they ran Russia. Fringe figures and eccentric movements cannot be counted out. If a system becomes weak enough and the opposition divided enough, if the ruling order is corrupt enough and people are angry enough, extremists can suddenly step into the center, where no one expects them. And after that it can take decades to undo the damage. We have been shocked too many times. Our imaginations need to expand to include the possibilities of such monsters and monstrosities. We were not adequately prepared.

For more information:

http://now/2017/11/06/830aecaa-bf41-11e7-9...

We are 100% volunteer and depend on your participation to sustain our efforts!

Get Involved

If you'd like to help with maintaining or developing the website, contact us.

Publish

Publish your stories and upcoming events on Indybay.

Topics

More

Search Indybay's Archives

Advanced Search

►

▼

IMC Network