From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

Philippines: The Punisher's dirty war on drugs

He’s been called a demagogue with a foul mouth backed up by bare-knuckle populism. But Philippines president, Rodrigo Duterte, aka “the Punisher”, has also embarked on a brutal drug war that is drawing international condemnation. Foreign Editor David Pratt reports.

Its local name is shabu. With a starting price of 31 US dollars a gram, methamphetamine is not a cheap buy for those Filipinos who live in the country’s impoverished barangays, or run down inner-city neighbourhoods and suburbs.

He’s been called a demagogue with a foul mouth backed up by bare-knuckle populism. But Philippines president, Rodrigo Duterte, aka “the Punisher”, has also embarked on a brutal drug war that is drawing international condemnation. Foreign Editor David Pratt reports.

Its local name is shabu. With a starting price of 31 US dollars a gram, methamphetamine is not a cheap buy for those Filipinos who live in the country’s impoverished barangays, or run down inner-city neighbourhoods and suburbs.

Life in such places however is incredibly cheap. It reaches rock bottom if you happen to be one of those drug dealers targeted by Rodrigo “Rody” Duterte, aka “the Punisher”, who also happens to be the current Philippines president.

This is a political leader for whom there is no shortage of nicknames. Not for good reason has he been called the “Trump of the Philippines” and “Duterte Harry”.

Duterte is a man who talks tough and fights dirty. Increasingly his presidency and the extra-judicial killings associated with it have drawn international condemnation, yet his domestic popularity ratings sit somewhere in the order of 90 per cent.

Duterte, his critics say, is nothing more than an ignorant demagogue with a foul mouth. Certainly this is a president that does not take kindly to criticism.

His choicest insult – “son of a bitch” was hurled at the Pope after the pontiff’s motorcade clogged Manila traffic during a visit. Then it was the turn of the US ambassador to the Philippines, whom he also derided as “gay”. Most recently, of course, it was the US President himself, Barack Obama, who came in for a Duterte tongue-lashing.

After weeks of criticism from Washington and Obama wanting to broach the subject of Duterte’s drug war killings at an Asian Nations summit earlier this month, the Philippines president made his feelings clear -“son of a whore, I will curse you in that forum,” he was quoted as saying.

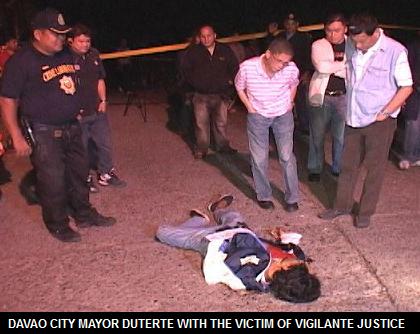

Only last week Duterte was again making controversial international headlines. Edgar Matobato, a self-confessed hitman for vigilante group the Davao Death Squad, testified that Duterte not only ordered the murder of criminals and opponents during his 22 years as mayor of Davao City but once personally “finished off” a justice department employee with an Uzi sub-machine gun.

Matobato was speaking as part of an inquiry by the Philippines Senate into the killings of more than 3,000 Filipinos, said to be part of Duterte’s ruthless and chaotic crackdown on drugs using paramilitary gangs that acted as a shadow police force.

The allegation that Duterte shot dead the justice department employee was matched by the equally lurid account of how other victims were allegedly disemboweled and dumped at sea and that Matobato on one occasion also fed a victim to a crocodile on behalf of the future president.

For his part Duterte, far from shying away from association with such violence, instead readily embraces it. Earlier this year, he nonchalantly entertained crowds at a rally in Iloilo City with a story of how he shot a fellow law student for disrespecting him. That the crowds’ response was one of mirth was an indication of the populist endorsement his crass and brutal approach has among many Filipinos.

Whatever truth there is to Matobato’s allegations presented last week, what is undeniable is the wanton ferocity of Duterte’s war on drugs. With his familiar refrain Duterte made very clear his intentions early on in his presidential run.

“All of you who are into drugs, you sons of bitches, I will really kill you,” he warned, promising that so many would die that “fish will grow fat” in Manila Bay from feasting on the remains.

If recent figures from the Philippine national police are anything to go by, this appears to have been no idle threat. So far more than 1,800 people have been killed as of September 14, just over two months since Duterte took office.

Some of these killings resulted from police operations, others were likely the work of vigilantes who may have been inspired by Duterte’s words. Other estimates put the numbers much higher with as many as 3,000 suspected dealers killed by police and unknown assailants.

To put this into some context it means that in less than three months Duterte has presided over three-quarters as many extrajudicial killings as there were lynchings of black people in America between 1877 and 1950.

In almost every case there was no due process, no trial, no presentation of evidence, just death. As Duterte himself has said, “due process has nothing to do with my mouth…there are no proceedings here, no lawyers.”

In this volatile free for all environment, there are many keen to exploit the anarchy and violence for their own ends.

The police have openly admitted that drug cartels have taken advantage of Duterte’s thumbs up to kill rivals or potential informants. Police impunity too has put many beyond the criminal fraternity on edge.

One long-time foreign resident of Manila, quoted in The Economist magazine recently, said that he has started to hear fellow expats talk about leaving. Many worry that an off-duty policeman could take issue with something a person did, shoot them and get away without any accountability. “This didn’t happen under Aquino,” the Manila resident said. “You didn’t feel there was a group of people who could kill someone and not go to jail.”

It is of course ordinary Filipinos themselves that have most to fear with horrifying cases of misconduct coming to light. In the impoverished barangay inner-city and suburban districts the poor often have no other opportunity for income but to become involved in the drug market at the lowest level.

Duterte’s war on drugs is little more than a war on the poor, says the International Peace Institute (IPI) an independent, not-for-profit think tank dedicated to promoting peace and sustainable development.

Back in 2009 the Davao Death Squad murdered suspects with the complicity of local officials in the city in which Duterte served as mayor. Most of these killings were perpetrated in broad daylight and the victims were mostly petty criminals, gang members, and street children.

Likewise today’s victims in Duterte’s mass execution are the low hanging fruit in the Philippines drug trade and come from the fringes of society.

Central to this process has been the so-called Operation Tokhang –“knock and plead” – now being conducted on a nationwide scale.

This is carried out by police officers visiting people whose names have been drawn from lists of drug suspects provided by barangay local officials.

“These individuals are compelled to report to their nearby police station, confess their alleged crimes, and sign declarations pledging to mend their ways,” says IPI.

These “surrender ceremonies” are conducted with much fanfare and media coverage, with participants labeled as offenders regardless of criminal liability actually being proven.

“Mothers are approaching me every week as their sons are threatened or listed in police precincts,” said Jean Enriquez, a feminist leader who belongs to a coalition of 50 Philippine human rights organisations. “Being listed could mean death.”

Duterte has simultaneously sanctioned the killing of suspects who do not participate in these processes, with the violence carried out by police and vigilante groups, comprising active and retired officers, former communist guerrillas, and even mercenary guns-for-hire.

The killings have become know as “cardboard justice” because suspects’ bodies are often dumped alongside signs scrawled with their alleged crimes. In some cases the victims are those who had attended a surrender ceremony but were nevertheless targeted.

As further evidence of this war on the poor, human rights workers tell of how affluent areas whose residents typically consume drugs such as cocaine and ecstasy, rather than the poor man’s shabu, are largely spared from the surrender ceremonies and the killings.

According to research undertaken by IPI, up-market, gated communities in Manila can even provide certification from homeowners’ associations that they are drug-free, which is enough to dissuade police officers from pursuing Tokhang activities. Far from encouraging vigilante justice against this section of society, Duterte is said also to have provided personal audiences to drug trade figures of much higher stature.

For the poorest on the sharp end of his brutal campaign, justice is only a dream. This was highlighted recently by the case of two impoverished Manila residents, Renato and Jaypee Bertes, a father and son who worked odd jobs and smoked shabu, before being arrested by police, beaten, and shot to death.

“The police said the two had tried to escape by seizing an officer’s gun,” the New York Times subsequently reported. “But a forensic examination found that the men had been incapacitated by the beatings before they were shot. Jaypee Bertes had a broken right arm,” the article concluded.

Then there was the case of 46year-old Restituto Castro. A father of four, he was neither a drug trade high flyer nor a pusher, too poor to afford the price of shabu. Instead Castro bought the drug on behalf of his friends in exchange for a “bump or two”.

According to Castro’s cousin he was about to give up dabbling with shabu as it didn’t sit well with his role as a family man.

Yet barely hours after then new Philippines President had given his first State of the Nation address, during which he vowed to destroy the drug trade by any means necessary, Castro was gunned how by unknown assailants. He was dispatched with a single bullet to the back of his head that same night, making Castro one of the first of 3,000 subsequent victims of the death squads.

When not killing petty criminals and those associated with the drug trade, Duterte has also made it open season on critics within the media. His rule has once again underlined the fact that the Philippines remain one of the most dangerous nations in the world for journalists.

“Most of those killed, to be frank, have done something. You won't be killed if you don't do anything wrong,” said Duterte by way of explanation, shortly before he was sworn into office.

In June, after two UN representatives condemned his “incitement to violence”, not only against drug dealers and criminals but also against journalists, the president’s response was equally uncompromising and belligerent. “F-ck you, UN,” he simply replied.

However the soaring rise in extrajudicial killings continues to invite scrutiny and condemnation from both international and domestic human right groups, but Duterte shows no signs of easing up.

Supporters say, why should he? The simple fact is that the Philippine electorate overwhelmingly chose Duterte precisely for his hardline stance on drugs they argue.

“The media may write headlines criticising the drug war, but my conversations with citizens, be it cab drivers, my uncles, or professionals, tell me there is strong support for it,” said Pia Ranada, a local reporter with Philippines online news portal The Rappler. She has received online death threats for her coverage of the President.

But many Filipinos remain appalled at the forces unleashed under Duterte’s regime. “We’re on a slippery slope toward tyranny,” says Philippine Senator Leila de Lima.

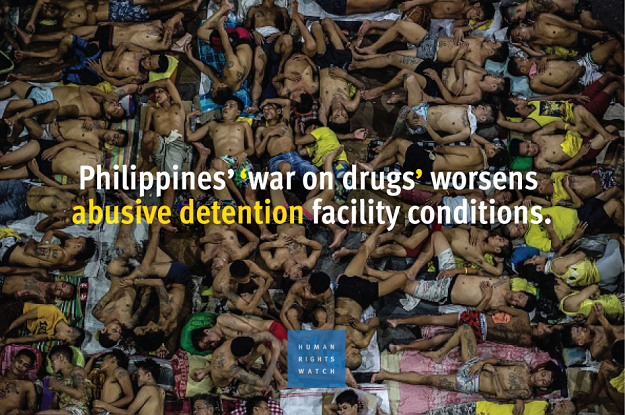

Right now Philippine city jails designed to hold 800 inmates are crowded to five times their capacity with those charged with drug crimes.

Rehabilitation centres, already few and far between, mean nothing to Duterte. The bodies, too, continue to show up on the street, many with the single word “peddler” scrawled on the cardboard notices lying alongside the corpses.

Human rights activists say this only further underlines Duterte’s stated intention of attempting to eradicate society’s “undesired.”

In a typical but nonetheless shocking remark while addressing Philippine troops at a military base recently, Duterte expressed how he really felt about drug users and those who have been killed.

“Crime against humanity? Duterte put it to the assembled troops. “In the first place, I’d like to be frank with you– are they humans?

He’s been called a demagogue with a foul mouth backed up by bare-knuckle populism. But Philippines president, Rodrigo Duterte, aka “the Punisher”, has also embarked on a brutal drug war that is drawing international condemnation. Foreign Editor David Pratt reports.

Its local name is shabu. With a starting price of 31 US dollars a gram, methamphetamine is not a cheap buy for those Filipinos who live in the country’s impoverished barangays, or run down inner-city neighbourhoods and suburbs.

Life in such places however is incredibly cheap. It reaches rock bottom if you happen to be one of those drug dealers targeted by Rodrigo “Rody” Duterte, aka “the Punisher”, who also happens to be the current Philippines president.

This is a political leader for whom there is no shortage of nicknames. Not for good reason has he been called the “Trump of the Philippines” and “Duterte Harry”.

Duterte is a man who talks tough and fights dirty. Increasingly his presidency and the extra-judicial killings associated with it have drawn international condemnation, yet his domestic popularity ratings sit somewhere in the order of 90 per cent.

Duterte, his critics say, is nothing more than an ignorant demagogue with a foul mouth. Certainly this is a president that does not take kindly to criticism.

His choicest insult – “son of a bitch” was hurled at the Pope after the pontiff’s motorcade clogged Manila traffic during a visit. Then it was the turn of the US ambassador to the Philippines, whom he also derided as “gay”. Most recently, of course, it was the US President himself, Barack Obama, who came in for a Duterte tongue-lashing.

After weeks of criticism from Washington and Obama wanting to broach the subject of Duterte’s drug war killings at an Asian Nations summit earlier this month, the Philippines president made his feelings clear -“son of a whore, I will curse you in that forum,” he was quoted as saying.

Only last week Duterte was again making controversial international headlines. Edgar Matobato, a self-confessed hitman for vigilante group the Davao Death Squad, testified that Duterte not only ordered the murder of criminals and opponents during his 22 years as mayor of Davao City but once personally “finished off” a justice department employee with an Uzi sub-machine gun.

Matobato was speaking as part of an inquiry by the Philippines Senate into the killings of more than 3,000 Filipinos, said to be part of Duterte’s ruthless and chaotic crackdown on drugs using paramilitary gangs that acted as a shadow police force.

The allegation that Duterte shot dead the justice department employee was matched by the equally lurid account of how other victims were allegedly disemboweled and dumped at sea and that Matobato on one occasion also fed a victim to a crocodile on behalf of the future president.

For his part Duterte, far from shying away from association with such violence, instead readily embraces it. Earlier this year, he nonchalantly entertained crowds at a rally in Iloilo City with a story of how he shot a fellow law student for disrespecting him. That the crowds’ response was one of mirth was an indication of the populist endorsement his crass and brutal approach has among many Filipinos.

Whatever truth there is to Matobato’s allegations presented last week, what is undeniable is the wanton ferocity of Duterte’s war on drugs. With his familiar refrain Duterte made very clear his intentions early on in his presidential run.

“All of you who are into drugs, you sons of bitches, I will really kill you,” he warned, promising that so many would die that “fish will grow fat” in Manila Bay from feasting on the remains.

If recent figures from the Philippine national police are anything to go by, this appears to have been no idle threat. So far more than 1,800 people have been killed as of September 14, just over two months since Duterte took office.

Some of these killings resulted from police operations, others were likely the work of vigilantes who may have been inspired by Duterte’s words. Other estimates put the numbers much higher with as many as 3,000 suspected dealers killed by police and unknown assailants.

To put this into some context it means that in less than three months Duterte has presided over three-quarters as many extrajudicial killings as there were lynchings of black people in America between 1877 and 1950.

In almost every case there was no due process, no trial, no presentation of evidence, just death. As Duterte himself has said, “due process has nothing to do with my mouth…there are no proceedings here, no lawyers.”

In this volatile free for all environment, there are many keen to exploit the anarchy and violence for their own ends.

The police have openly admitted that drug cartels have taken advantage of Duterte’s thumbs up to kill rivals or potential informants. Police impunity too has put many beyond the criminal fraternity on edge.

One long-time foreign resident of Manila, quoted in The Economist magazine recently, said that he has started to hear fellow expats talk about leaving. Many worry that an off-duty policeman could take issue with something a person did, shoot them and get away without any accountability. “This didn’t happen under Aquino,” the Manila resident said. “You didn’t feel there was a group of people who could kill someone and not go to jail.”

It is of course ordinary Filipinos themselves that have most to fear with horrifying cases of misconduct coming to light. In the impoverished barangay inner-city and suburban districts the poor often have no other opportunity for income but to become involved in the drug market at the lowest level.

Duterte’s war on drugs is little more than a war on the poor, says the International Peace Institute (IPI) an independent, not-for-profit think tank dedicated to promoting peace and sustainable development.

Back in 2009 the Davao Death Squad murdered suspects with the complicity of local officials in the city in which Duterte served as mayor. Most of these killings were perpetrated in broad daylight and the victims were mostly petty criminals, gang members, and street children.

Likewise today’s victims in Duterte’s mass execution are the low hanging fruit in the Philippines drug trade and come from the fringes of society.

Central to this process has been the so-called Operation Tokhang –“knock and plead” – now being conducted on a nationwide scale.

This is carried out by police officers visiting people whose names have been drawn from lists of drug suspects provided by barangay local officials.

“These individuals are compelled to report to their nearby police station, confess their alleged crimes, and sign declarations pledging to mend their ways,” says IPI.

These “surrender ceremonies” are conducted with much fanfare and media coverage, with participants labeled as offenders regardless of criminal liability actually being proven.

“Mothers are approaching me every week as their sons are threatened or listed in police precincts,” said Jean Enriquez, a feminist leader who belongs to a coalition of 50 Philippine human rights organisations. “Being listed could mean death.”

Duterte has simultaneously sanctioned the killing of suspects who do not participate in these processes, with the violence carried out by police and vigilante groups, comprising active and retired officers, former communist guerrillas, and even mercenary guns-for-hire.

The killings have become know as “cardboard justice” because suspects’ bodies are often dumped alongside signs scrawled with their alleged crimes. In some cases the victims are those who had attended a surrender ceremony but were nevertheless targeted.

As further evidence of this war on the poor, human rights workers tell of how affluent areas whose residents typically consume drugs such as cocaine and ecstasy, rather than the poor man’s shabu, are largely spared from the surrender ceremonies and the killings.

According to research undertaken by IPI, up-market, gated communities in Manila can even provide certification from homeowners’ associations that they are drug-free, which is enough to dissuade police officers from pursuing Tokhang activities. Far from encouraging vigilante justice against this section of society, Duterte is said also to have provided personal audiences to drug trade figures of much higher stature.

For the poorest on the sharp end of his brutal campaign, justice is only a dream. This was highlighted recently by the case of two impoverished Manila residents, Renato and Jaypee Bertes, a father and son who worked odd jobs and smoked shabu, before being arrested by police, beaten, and shot to death.

“The police said the two had tried to escape by seizing an officer’s gun,” the New York Times subsequently reported. “But a forensic examination found that the men had been incapacitated by the beatings before they were shot. Jaypee Bertes had a broken right arm,” the article concluded.

Then there was the case of 46year-old Restituto Castro. A father of four, he was neither a drug trade high flyer nor a pusher, too poor to afford the price of shabu. Instead Castro bought the drug on behalf of his friends in exchange for a “bump or two”.

According to Castro’s cousin he was about to give up dabbling with shabu as it didn’t sit well with his role as a family man.

Yet barely hours after then new Philippines President had given his first State of the Nation address, during which he vowed to destroy the drug trade by any means necessary, Castro was gunned how by unknown assailants. He was dispatched with a single bullet to the back of his head that same night, making Castro one of the first of 3,000 subsequent victims of the death squads.

When not killing petty criminals and those associated with the drug trade, Duterte has also made it open season on critics within the media. His rule has once again underlined the fact that the Philippines remain one of the most dangerous nations in the world for journalists.

“Most of those killed, to be frank, have done something. You won't be killed if you don't do anything wrong,” said Duterte by way of explanation, shortly before he was sworn into office.

In June, after two UN representatives condemned his “incitement to violence”, not only against drug dealers and criminals but also against journalists, the president’s response was equally uncompromising and belligerent. “F-ck you, UN,” he simply replied.

However the soaring rise in extrajudicial killings continues to invite scrutiny and condemnation from both international and domestic human right groups, but Duterte shows no signs of easing up.

Supporters say, why should he? The simple fact is that the Philippine electorate overwhelmingly chose Duterte precisely for his hardline stance on drugs they argue.

“The media may write headlines criticising the drug war, but my conversations with citizens, be it cab drivers, my uncles, or professionals, tell me there is strong support for it,” said Pia Ranada, a local reporter with Philippines online news portal The Rappler. She has received online death threats for her coverage of the President.

But many Filipinos remain appalled at the forces unleashed under Duterte’s regime. “We’re on a slippery slope toward tyranny,” says Philippine Senator Leila de Lima.

Right now Philippine city jails designed to hold 800 inmates are crowded to five times their capacity with those charged with drug crimes.

Rehabilitation centres, already few and far between, mean nothing to Duterte. The bodies, too, continue to show up on the street, many with the single word “peddler” scrawled on the cardboard notices lying alongside the corpses.

Human rights activists say this only further underlines Duterte’s stated intention of attempting to eradicate society’s “undesired.”

In a typical but nonetheless shocking remark while addressing Philippine troops at a military base recently, Duterte expressed how he really felt about drug users and those who have been killed.

“Crime against humanity? Duterte put it to the assembled troops. “In the first place, I’d like to be frank with you– are they humans?

Add Your Comments

We are 100% volunteer and depend on your participation to sustain our efforts!

Get Involved

If you'd like to help with maintaining or developing the website, contact us.

Publish

Publish your stories and upcoming events on Indybay.

Topics

More

Search Indybay's Archives

Advanced Search

►

▼

IMC Network