From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

Americans want it all, and hang the consequences

Andrew Gumbel remarks that in America "enviornmental conciousness" carries a steep price tag-- but, no matter-- for its people who "want it all."

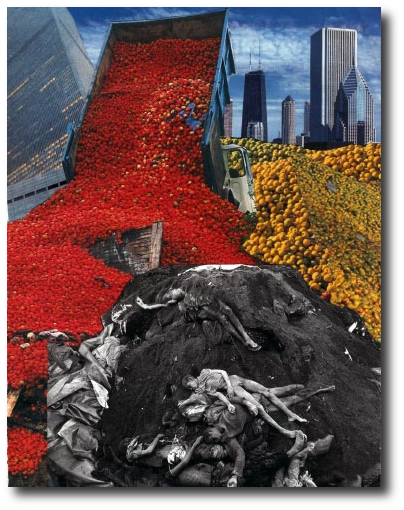

(illustration by Michael Dickinson yabanji.tripod.com)

(illustration by Michael Dickinson yabanji.tripod.com)

Andrew Gumbel: Americans want it all, and hang the consequences

Published: 11 October 2006

In the 1970s film Five Easy Pieces, Toni Basil plays a hippie who is hitch-hiking to Alaska (in Jack Nicholson's car) because it's the only place she can think of that is still clean. The rest of the US, she frets, is filling up with more and more "crap". "They got so many stores and stuff and junk full of crap, I can't believe it," she says. "Pretty soon, there won't be any room for man."

The film came out in 1971 and coincided almost exactly with the birth of the modern environmental movement, the launch of Earth Day, and the realisation that the limitless consumption of the capitalist-era American Dream simply could not go on forever. In the intervening years, the accumulation of rubbish has continued pretty much unabated - not helped by a population increase of almost 100 million people, and an orgy of environmental deregulation of industry. But so too has the level of anxiety about the consequences.

Today's counterparts to Toni Basil's character are still relatively marginal figures, if less eccentric in their obsessions. They also tend to be rich and successful - environmental consciousness now carries a high price tag.

Of course, they go to open-air farmer's markets to seek out pesticide-free organic fruit and vegetables supplied by small, family growers but they also pay a premium for it. They might drive energy-efficient, low-emission hybrid cars but they also pay more for their fancy petrol-electric engines than they are likely to recuperate in petrol savings over the lifetime of their car.

The same is true for many other aspects of environmental consciousness. Who uses washable cloth nappies rather than throwaway ones? Who has solar panels installed on their roof? Only those who can afford them.

The severely limited impulse to conserve is not only about economics. It is also deeply cultural. The United States is a place where the prevailing instinct is to want it all, no matter the consequences. Sure, there may be wars in the Middle East, Islamic militants on the march, smog in the air, pollutants in the water, hurricanes, floods and other tangible side-effects of global warming but that's not going to stop most people from hankering after a big car and a big house with state-of-the-art gadgets.

Cutting back is not cool or sexy. Given the choice between laboriously reviving old city centres with apartment renovations and corner shops, or ripping up cornfields to create suburban developments with huge houses and monster shopping malls, most Americans opt for the monster.

People certainly have mixed feelings. At the height of the Iraq war, it was not uncommon to see huge, gas-guzzling four-wheel-drives sporting "No Blood for Oil" stickers. Americans aren't happy about their obesity epidemic or their tendency to overspend in grocery stores or over-order in restaurants, even while they consume 200bn calories a day more than they need and throw away around 200,000 tons of edible food each day.

But will anything ever change? Telling Americans to consume less doesn't work. Giving them environmentally smarter versions of the same things - more fuel-efficient cars, better insulated houses, less heavily packaged food - may be a more promising avenue. Until the government, however, gets serious about forcing manufacturers to produce these things, the age of the more rational American consumer will remain a distant prospect.

In the 1970s film Five Easy Pieces, Toni Basil plays a hippie who is hitch-hiking to Alaska (in Jack Nicholson's car) because it's the only place she can think of that is still clean. The rest of the US, she frets, is filling up with more and more "crap". "They got so many stores and stuff and junk full of crap, I can't believe it," she says. "Pretty soon, there won't be any room for man."

The film came out in 1971 and coincided almost exactly with the birth of the modern environmental movement, the launch of Earth Day, and the realisation that the limitless consumption of the capitalist-era American Dream simply could not go on forever. In the intervening years, the accumulation of rubbish has continued pretty much unabated - not helped by a population increase of almost 100 million people, and an orgy of environmental deregulation of industry. But so too has the level of anxiety about the consequences.

Today's counterparts to Toni Basil's character are still relatively marginal figures, if less eccentric in their obsessions. They also tend to be rich and successful - environmental consciousness now carries a high price tag.

Of course, they go to open-air farmer's markets to seek out pesticide-free organic fruit and vegetables supplied by small, family growers but they also pay a premium for it. They might drive energy-efficient, low-emission hybrid cars but they also pay more for their fancy petrol-electric engines than they are likely to recuperate in petrol savings over the lifetime of their car.

The same is true for many other aspects of environmental consciousness. Who uses washable cloth nappies rather than throwaway ones? Who has solar panels installed on their roof? Only those who can afford them.

The severely limited impulse to conserve is not only about economics. It is also deeply cultural. The United States is a place where the prevailing instinct is to want it all, no matter the consequences. Sure, there may be wars in the Middle East, Islamic militants on the march, smog in the air, pollutants in the water, hurricanes, floods and other tangible side-effects of global warming but that's not going to stop most people from hankering after a big car and a big house with state-of-the-art gadgets.

Cutting back is not cool or sexy. Given the choice between laboriously reviving old city centres with apartment renovations and corner shops, or ripping up cornfields to create suburban developments with huge houses and monster shopping malls, most Americans opt for the monster.

People certainly have mixed feelings. At the height of the Iraq war, it was not uncommon to see huge, gas-guzzling four-wheel-drives sporting "No Blood for Oil" stickers. Americans aren't happy about their obesity epidemic or their tendency to overspend in grocery stores or over-order in restaurants, even while they consume 200bn calories a day more than they need and throw away around 200,000 tons of edible food each day.

But will anything ever change? Telling Americans to consume less doesn't work. Giving them environmentally smarter versions of the same things - more fuel-efficient cars, better insulated houses, less heavily packaged food - may be a more promising avenue. Until the government, however, gets serious about forcing manufacturers to produce these things, the age of the more rational American consumer will remain a distant prospect.

Published: 11 October 2006

In the 1970s film Five Easy Pieces, Toni Basil plays a hippie who is hitch-hiking to Alaska (in Jack Nicholson's car) because it's the only place she can think of that is still clean. The rest of the US, she frets, is filling up with more and more "crap". "They got so many stores and stuff and junk full of crap, I can't believe it," she says. "Pretty soon, there won't be any room for man."

The film came out in 1971 and coincided almost exactly with the birth of the modern environmental movement, the launch of Earth Day, and the realisation that the limitless consumption of the capitalist-era American Dream simply could not go on forever. In the intervening years, the accumulation of rubbish has continued pretty much unabated - not helped by a population increase of almost 100 million people, and an orgy of environmental deregulation of industry. But so too has the level of anxiety about the consequences.

Today's counterparts to Toni Basil's character are still relatively marginal figures, if less eccentric in their obsessions. They also tend to be rich and successful - environmental consciousness now carries a high price tag.

Of course, they go to open-air farmer's markets to seek out pesticide-free organic fruit and vegetables supplied by small, family growers but they also pay a premium for it. They might drive energy-efficient, low-emission hybrid cars but they also pay more for their fancy petrol-electric engines than they are likely to recuperate in petrol savings over the lifetime of their car.

The same is true for many other aspects of environmental consciousness. Who uses washable cloth nappies rather than throwaway ones? Who has solar panels installed on their roof? Only those who can afford them.

The severely limited impulse to conserve is not only about economics. It is also deeply cultural. The United States is a place where the prevailing instinct is to want it all, no matter the consequences. Sure, there may be wars in the Middle East, Islamic militants on the march, smog in the air, pollutants in the water, hurricanes, floods and other tangible side-effects of global warming but that's not going to stop most people from hankering after a big car and a big house with state-of-the-art gadgets.

Cutting back is not cool or sexy. Given the choice between laboriously reviving old city centres with apartment renovations and corner shops, or ripping up cornfields to create suburban developments with huge houses and monster shopping malls, most Americans opt for the monster.

People certainly have mixed feelings. At the height of the Iraq war, it was not uncommon to see huge, gas-guzzling four-wheel-drives sporting "No Blood for Oil" stickers. Americans aren't happy about their obesity epidemic or their tendency to overspend in grocery stores or over-order in restaurants, even while they consume 200bn calories a day more than they need and throw away around 200,000 tons of edible food each day.

But will anything ever change? Telling Americans to consume less doesn't work. Giving them environmentally smarter versions of the same things - more fuel-efficient cars, better insulated houses, less heavily packaged food - may be a more promising avenue. Until the government, however, gets serious about forcing manufacturers to produce these things, the age of the more rational American consumer will remain a distant prospect.

In the 1970s film Five Easy Pieces, Toni Basil plays a hippie who is hitch-hiking to Alaska (in Jack Nicholson's car) because it's the only place she can think of that is still clean. The rest of the US, she frets, is filling up with more and more "crap". "They got so many stores and stuff and junk full of crap, I can't believe it," she says. "Pretty soon, there won't be any room for man."

The film came out in 1971 and coincided almost exactly with the birth of the modern environmental movement, the launch of Earth Day, and the realisation that the limitless consumption of the capitalist-era American Dream simply could not go on forever. In the intervening years, the accumulation of rubbish has continued pretty much unabated - not helped by a population increase of almost 100 million people, and an orgy of environmental deregulation of industry. But so too has the level of anxiety about the consequences.

Today's counterparts to Toni Basil's character are still relatively marginal figures, if less eccentric in their obsessions. They also tend to be rich and successful - environmental consciousness now carries a high price tag.

Of course, they go to open-air farmer's markets to seek out pesticide-free organic fruit and vegetables supplied by small, family growers but they also pay a premium for it. They might drive energy-efficient, low-emission hybrid cars but they also pay more for their fancy petrol-electric engines than they are likely to recuperate in petrol savings over the lifetime of their car.

The same is true for many other aspects of environmental consciousness. Who uses washable cloth nappies rather than throwaway ones? Who has solar panels installed on their roof? Only those who can afford them.

The severely limited impulse to conserve is not only about economics. It is also deeply cultural. The United States is a place where the prevailing instinct is to want it all, no matter the consequences. Sure, there may be wars in the Middle East, Islamic militants on the march, smog in the air, pollutants in the water, hurricanes, floods and other tangible side-effects of global warming but that's not going to stop most people from hankering after a big car and a big house with state-of-the-art gadgets.

Cutting back is not cool or sexy. Given the choice between laboriously reviving old city centres with apartment renovations and corner shops, or ripping up cornfields to create suburban developments with huge houses and monster shopping malls, most Americans opt for the monster.

People certainly have mixed feelings. At the height of the Iraq war, it was not uncommon to see huge, gas-guzzling four-wheel-drives sporting "No Blood for Oil" stickers. Americans aren't happy about their obesity epidemic or their tendency to overspend in grocery stores or over-order in restaurants, even while they consume 200bn calories a day more than they need and throw away around 200,000 tons of edible food each day.

But will anything ever change? Telling Americans to consume less doesn't work. Giving them environmentally smarter versions of the same things - more fuel-efficient cars, better insulated houses, less heavily packaged food - may be a more promising avenue. Until the government, however, gets serious about forcing manufacturers to produce these things, the age of the more rational American consumer will remain a distant prospect.

For more information:

http://comment.independent.co.uk/commentat...

Add Your Comments

We are 100% volunteer and depend on your participation to sustain our efforts!

Get Involved

If you'd like to help with maintaining or developing the website, contact us.

Publish

Publish your stories and upcoming events on Indybay.

Topics

More

Search Indybay's Archives

Advanced Search

►

▼

IMC Network