From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

Africa: The New Frontier for Imperial Oil

In his State of the Union address, George Dubya said that the U.S. is “addicted to oil.” What he didn’t say was that post-WWII oil policy – which has been a central plank of U.S. foreign policy since President Roosevelt met King Saud of Saudi Arabia and cobbled together their ‘special relationship’ in 1945 – is in shambles. The pillars of this policy – Iran, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf oil states, and Venezuela – are hardly models of U.S. spheres of influence. With surplus capacity in the world oil market at an all-time low, and speculative capacity in the commodity exchanges at an all-time high, the transnational oil companies and the oil producing states are awash in petro-dollars – but the days of cheap oil seem to be fast disappearing.

It is no surprise, then, that other suppliers of oil should be very much on the Bush radar screen (since the alternatives of conservation strategies or increased gas taxes are conspicuously absent). The Cheney Energy Report in 2001 made the point about MidEast oil dependency long before the State of the Union. A recent headline in the Financial Times (March 1, 2006) makes the agenda crystal clear: Africa is the “continent all set to balance power.”

Though not as rich in hydrocarbons as Saudi Arabia, Africa nevertheless is, said the Financial Times, “the subject of fierce competition by energy com¬panies.” IHS Energy – one of the oil industry’s major consulting companies – expects African oil, especially along the Atlantic margins (the so-called Gulf of Guinea), to attract “huge exploration investment” and contribute over 30 percent of world liquid hydrocarbon production by 2010. Over the last five years, Africa has contributed one in every four barrels of new oil discovered outside of Northern America. A new scramble for Africa is afoot. The battleground is the continent’s oilfields – the looting of what the Times calls Africa’s “copious reserves of natural gas and its sweet light oil.”

Energy security is the name of the game. The Council of Foreign Rela¬tions’ call for a new approach to Africa in its report “More than Humanitarianism (2005) focuses on Africa’s “growing strategic importance” for U.S. policy. This means cheap and stable oil imports but also keeping the Chinese – important new actors in the African oil business – and Islamic terror at bay. (Africa is, according to the intelligence community, the ‘new frontier’ in the fight against revolutionary Islam.) It turns out that energy security is a terrifying hybrid of the old and the new: primitive accumulation coupled to American militarism and the war on terror. Will it work?

AFRICA’S BLACK GOLD

Currently Africa is the center of a major oil boom. The continent accounts for roughly 10 percent of world oil output and 9.3 percent of known reserves. Though oil fields in Africa are generally smaller and deeper than the Middle East - and production costs are accordingly 3-4 times higher - African crude is generally ‘sweet’ and low in sulfur, making it attractive to U.S. importers. The twelve major African oil producers - dominated by Nigeria, Algeria, Libya, and Angola, which collectively account for 85 percent of African output - are highly oil-dependent. In Nigeria, for example, 85 percent of government revenues, 98 percent of exports, and almost half of gross domestic product are derived from oil earnings. In short, the governments of African oil states are ‘oil dependencies.’ They are also – and here they share an affinity with oil producers in the other Gulf and in the Caspian – categorized as among the most corrupt in the world, mirroring the global oil industry in which they are embedded. For the impoverished populations of these wealthy oil states, black gold is nothing more than a mirage; oil has brought corruption, waste, repression, a venal and authoritarian local ‘oilygarchy,’ and economic stagnation.

The jewel in the crown is the West African Gulf of Guinea, encompassing the rich on- and offshore fields stretching from Nigeria to Angola. Nigeria and Angola alone account for almost half of African output, nearly 4 million barrels per day. U.S. oil companies have invested $40 billion in Africa over the last decade (and another $30 billion is expected between 2005 and 2010). Oil investment now represents over 50 percent of all foreign direct investment in the continent.

On this canvas of African oil security and a new scramble for the continent, the recent events in Nigeria and the crisis in the oilfields of the Niger Delta are of enormous importance. In late 2005 and early 2006 there was a massive escalation in violent attacks on oil installations by ethnic militants (primarily Ijaw, the largest ethnic group in the oil producing region) including the taking of oil hostages by a largely unknown militant group MEND (the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta). As a result of this escala¬tion (and events in Iran and Venezuela), oil markets remain very jittery.

The recent hostage-taking and at¬tacks on oil infrastructure in the Delta, however, are simply the tip of a political iceberg. Earlier in 2005, political representatives from the oil-producing region walked out of a national meet¬ing on the distribution of oil revenues. A few months later the Obasanjo government arrested a Delta militant and insurgency leader on treason charges which prompted renewed political turbulence across the region. Since the late 1990s, there has been a very substantial escalation of violence across the Delta oil fields, accompanied by major attacks on oil facilities (it is estimated that more than one thousand people die each year from oil-related violence). A year before 9/11, the U.S. Department of State, in its annual report on ‘global terrorism,’ identified the Niger Delta as a volatile breeding ground for militant “impoverished ethnic groups” for whom terrorist acts (abduction, hostage taking, kidnapping and extra-judicial killings) were part of their stock in trade.

Since the late 1990s, the Niger Delta has been pretty much ungovernable. A 2003 report prepared for the Nigerian National Petroleum Company, entitled “Back from the Brink,” painted a gloomy “risk audit” for Big Oil. A leaked report by Shell in the same year explicitly stated that their “license to operate” in Nigeria was in question. And with good reason. Between 1998 and 2003, there were 400 “vandalizations” on company facilities per year (581 between January and September 2004), and oil losses amounted to $1 billion annually. Yet in the Delta various NGOs have demonstrated that at least some of this vandalization is the result of poor maintenance by the oil companies. Nevertheless, the mobilizations against the companies have been various: demonstrations and blockades against oil facilities; occupations of flow stations and platforms; sabotage of pipelines; oil “bunkering,” or theft (from hot-tapping fuel lines to large-scale appropriation of crude from flow stations); litigation against the companies; hostage taking and strikes.

Mounting violence in 2003 resulted in many deaths and widespread com¬munity destruction and dislocation in the Warri region of the western Delta. The protests and conflicts were complex and multi-faceted. In Warri town – a centre of the oil industry – conflicts between three differing ethnic groups were prompted by fraudulent local elec¬tions and a longstanding battle over the delineation of electoral wards and local government jurisdictions as a way of gaining access to government oil revenues. In the creeks and oil-producing communities protests erupted over company policies and longstanding grievances over oil spills and company practices, especially employment of local indigenes. All of this was overlaid by a lucrative oil theft business, organized by high ranking military, politicians, and civil servants, in which militant Ijaw youth (the largest and most militant minority group in the Delta) were fighting to get a cut of the illegal “bunkering” trade (that in 2003 siphoned off a staggering 15 percent of national production). Violence across the oil fields prompted all the major oil companies to withdraw their staff, close down operations, and reduce output by more than 750,000 barrels per day (40 percent of the national output). This, in turn, provoked President Obasanjo to dispatch large troop deployment to the oil-producing creeks. In April 2004, another wave of violence erupted around oil installations, this time amid the presence of two militias led by Ateke Tom (the Niger Delta Vigilante) and Alhaji Asari (the Niger Delta People’s Volunteer Force), each driven, and partly funded, by oil monies. By the end of April 2004, Shell alone was losing production of up to 370,000 barrels per day, largely in the Western Delta.

Ten years after the hanging of novelist and minority rights advocate Ken Saro-Wiwa, conditions in the oilfields remain abysmal. An Amnesty International report (2005), entitled “Ten Years On: Injustice and Violence Haunt the Oil Delta,” declared that things have only gotten worse. Security forces still operate with impunity, the government has refused to protect communities in oil producing areas while providing security to the oil industry, and, above all, the oil companies themselves (Shell, Chevron, AGIP, TotalElfFina) bear a share of the responsibility for the appalling misery and the political instability across the region.

The most recent events in Nigeria mark something of a watershed. After taking international oil workers hostage, one of MEND’s demands was the release of two Ijaw leaders. On January 29, 2006 these hostages were released unharmed although the Ijaw leaders in question remained under arrest in Abuja, the Nigerian capital. MEND stated that the release of the hostages was made on “purely humanitarian grounds” and were quoted as saying: “This release does not signify a ceasefire or softening of our position to destroy the oil export capability of the Nigerian government.”

By the first week in February, MEND had contacted the Nigerian press directly, calling for the “international community to evacuate from the Niger Delta by February 12, or ‘face violent attacks.’” Two weeks later, MEND claimed responsibility for attacking a Federal naval vessel and for kidnapping nine workers employed by the oil servicing company Willbros, apparently in retaliation for an attack by the Nigerian military on a community in the Western Delta. The Nigerian government claimed they had attacked barges involved in the contraband oil trade. The geography of the Nigerian Delta, a maze of creeks and swamps, and its marginalization from state transportation and communication infrastructure, make the region extremely difficult to police. This isolation amplifies the significance of MEND’s threats to destroy facilities. Behind these threats is the prospect of attacks on the enormously expensive liquefied natural gas plants in Bonny and another under construction at Escravos. In the days following the violence, the prices of a barrel of oil increased by almost $1.50 and Shell and Chevron indicated that their production in Nigeria had been cut by 15 percent.

ANOTHER COLOMBIA

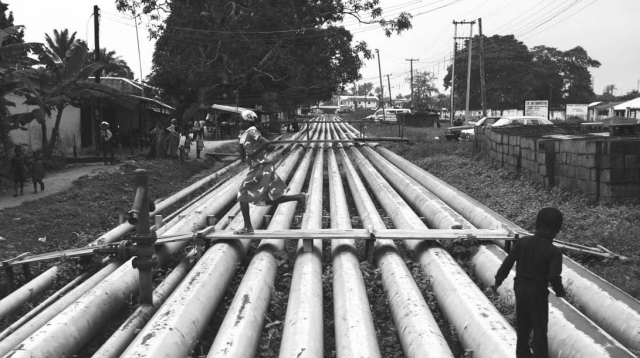

Nigeria reveals all of the contradictions of the new U.S. energy policy in which African suppliers are expected to play an expanded role. Nigeria is an archetypical “oil nation.” Oil dominates economic and political life. Crude oil production runs currently at more than 2.1 million barrels per day valued at more than $20 billion at 2004 prices. Nigeria’s oil sector now represents a vast domestic industrial infrastructure: more than three hundred oil fields, 5,284 wells, 7,000 kilometers of pipelines, ten export terminals, 275 flow stations, ten gas plants, four refineries, and massive liquefied natural gas (LNG) projects.

A multi-billion dollar oil industry has, however, proved to be a little more than a nightmare. To inventory the ‘achievements’ of Nigerian oil development is a salutary exercise: 85 percent of oil revenues accrue to 1 percent of the population; perhaps $100 billion of $400 billion in revenues since 1970 have simply gone “missing” (The anti-corruption chief Nuhu Ribadu, claimed that in 2003 70 percent of the country’s oil wealth was stolen or wasted; by 2005 it was “only” 40 percent). Between 1965-2004, the per capital income fell from $250 to $212 and income distribution deteriorated markedly over the same period. Between 1970 and 2000 in Nigeria, the number of people subsisting on less than one dollar per day grew from 36 percent to more than 70 percent: from 19 million to a staggering 90 million. According to the IMF, oil “did not seem to add to the standard of living” and “could have contributed to a decline in the standard of living.” Over the last decade GDP per capita and life expectancy have both fallen.

Essentially, petro-development has resulted in the terrifying and catastrophic failure of secular nationalist development. It is sometimes hard to grasp the full consequences and depth of this failure. From the vantage point of the Niger Delta—but no less from the vast slum worlds of Kano or Lagos—development and oil wealth is a cruel joke. These paradoxes and contradictions of oil are nowhere greater than on the oilfields of the Niger Delta. In the oil rich states there is one doctor for every 150,000 inhabitants. “The oil-based economy has wrought only poverty, state violence, and a dying ecosystem,” said Nigerian scholar-activist Ike Okonta. The government’s presence, Okonta says, “is only felt in the form of the machine gun and jackboots.” It is no great surprise that a half century of neglect in the shadow of black gold has made for explosive politics.

Overlaid upon the corrupt Nigerian petro-state, a volatile mix of forces reveal the deadly operations of imperial oil. First, geo-strategic interests in oil employ military and other security forces (including the private security forces and local residents, contracted by the oil companies.) Second, the transnational oil business – the majors, the independents and the vast service industry – are actively involved in the process of local development through new oil company interventions in which the NGO sector and local communities are now drawn into new ‘partnerships.’ Third, multilateral development agencies (the IMF and the IBRD) and financial corpora¬tions like the export credit agencies appear as key “brokers” in the construction and expansion of the energy sectors in oil-producing states. Afterwards, the multilaterals are pressured to become the enforcers of transparency among governments and oil companies.) And not least, there is the relationship between oil and the shady world of drugs, illicit wealth (oil theft for example), mercenaries, and the black economy. This entire oil complex is a sort of corporate enclave economy that is at once violent, unstable, heavily militarized, and largely unaccountable.

The struggle for resource control has taken center stage over the last decade in Nigeria as the Niger Delta has become more volatile. The question is: what is the U.S. prepared to do to keep the oil flowing to feed its addiction? Nigeria is now awash with oil money as the 2007 elections approach, and if the past is any guide, much of this will be deployed to fund political thuggery, intimidation, and outright fraud by the ruling political classes. President Obasanjo is considering a run for a third term – requiring a constitutional amendment – which in turn would be destabilizing in the Muslim north and in the oil producing delta. The increasing U.S. military presence in the Gulf and its anti-terror forces in the north are naturally seen within Nigeria as the price the Bush regime is prepared to pay to keep American cars on the road. An Iraq or Colombia option – civil war and American militarization – cannot be discounted. Blood and oil are never far apart.

Though not as rich in hydrocarbons as Saudi Arabia, Africa nevertheless is, said the Financial Times, “the subject of fierce competition by energy com¬panies.” IHS Energy – one of the oil industry’s major consulting companies – expects African oil, especially along the Atlantic margins (the so-called Gulf of Guinea), to attract “huge exploration investment” and contribute over 30 percent of world liquid hydrocarbon production by 2010. Over the last five years, Africa has contributed one in every four barrels of new oil discovered outside of Northern America. A new scramble for Africa is afoot. The battleground is the continent’s oilfields – the looting of what the Times calls Africa’s “copious reserves of natural gas and its sweet light oil.”

Energy security is the name of the game. The Council of Foreign Rela¬tions’ call for a new approach to Africa in its report “More than Humanitarianism (2005) focuses on Africa’s “growing strategic importance” for U.S. policy. This means cheap and stable oil imports but also keeping the Chinese – important new actors in the African oil business – and Islamic terror at bay. (Africa is, according to the intelligence community, the ‘new frontier’ in the fight against revolutionary Islam.) It turns out that energy security is a terrifying hybrid of the old and the new: primitive accumulation coupled to American militarism and the war on terror. Will it work?

AFRICA’S BLACK GOLD

Currently Africa is the center of a major oil boom. The continent accounts for roughly 10 percent of world oil output and 9.3 percent of known reserves. Though oil fields in Africa are generally smaller and deeper than the Middle East - and production costs are accordingly 3-4 times higher - African crude is generally ‘sweet’ and low in sulfur, making it attractive to U.S. importers. The twelve major African oil producers - dominated by Nigeria, Algeria, Libya, and Angola, which collectively account for 85 percent of African output - are highly oil-dependent. In Nigeria, for example, 85 percent of government revenues, 98 percent of exports, and almost half of gross domestic product are derived from oil earnings. In short, the governments of African oil states are ‘oil dependencies.’ They are also – and here they share an affinity with oil producers in the other Gulf and in the Caspian – categorized as among the most corrupt in the world, mirroring the global oil industry in which they are embedded. For the impoverished populations of these wealthy oil states, black gold is nothing more than a mirage; oil has brought corruption, waste, repression, a venal and authoritarian local ‘oilygarchy,’ and economic stagnation.

The jewel in the crown is the West African Gulf of Guinea, encompassing the rich on- and offshore fields stretching from Nigeria to Angola. Nigeria and Angola alone account for almost half of African output, nearly 4 million barrels per day. U.S. oil companies have invested $40 billion in Africa over the last decade (and another $30 billion is expected between 2005 and 2010). Oil investment now represents over 50 percent of all foreign direct investment in the continent.

On this canvas of African oil security and a new scramble for the continent, the recent events in Nigeria and the crisis in the oilfields of the Niger Delta are of enormous importance. In late 2005 and early 2006 there was a massive escalation in violent attacks on oil installations by ethnic militants (primarily Ijaw, the largest ethnic group in the oil producing region) including the taking of oil hostages by a largely unknown militant group MEND (the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta). As a result of this escala¬tion (and events in Iran and Venezuela), oil markets remain very jittery.

The recent hostage-taking and at¬tacks on oil infrastructure in the Delta, however, are simply the tip of a political iceberg. Earlier in 2005, political representatives from the oil-producing region walked out of a national meet¬ing on the distribution of oil revenues. A few months later the Obasanjo government arrested a Delta militant and insurgency leader on treason charges which prompted renewed political turbulence across the region. Since the late 1990s, there has been a very substantial escalation of violence across the Delta oil fields, accompanied by major attacks on oil facilities (it is estimated that more than one thousand people die each year from oil-related violence). A year before 9/11, the U.S. Department of State, in its annual report on ‘global terrorism,’ identified the Niger Delta as a volatile breeding ground for militant “impoverished ethnic groups” for whom terrorist acts (abduction, hostage taking, kidnapping and extra-judicial killings) were part of their stock in trade.

Since the late 1990s, the Niger Delta has been pretty much ungovernable. A 2003 report prepared for the Nigerian National Petroleum Company, entitled “Back from the Brink,” painted a gloomy “risk audit” for Big Oil. A leaked report by Shell in the same year explicitly stated that their “license to operate” in Nigeria was in question. And with good reason. Between 1998 and 2003, there were 400 “vandalizations” on company facilities per year (581 between January and September 2004), and oil losses amounted to $1 billion annually. Yet in the Delta various NGOs have demonstrated that at least some of this vandalization is the result of poor maintenance by the oil companies. Nevertheless, the mobilizations against the companies have been various: demonstrations and blockades against oil facilities; occupations of flow stations and platforms; sabotage of pipelines; oil “bunkering,” or theft (from hot-tapping fuel lines to large-scale appropriation of crude from flow stations); litigation against the companies; hostage taking and strikes.

Mounting violence in 2003 resulted in many deaths and widespread com¬munity destruction and dislocation in the Warri region of the western Delta. The protests and conflicts were complex and multi-faceted. In Warri town – a centre of the oil industry – conflicts between three differing ethnic groups were prompted by fraudulent local elec¬tions and a longstanding battle over the delineation of electoral wards and local government jurisdictions as a way of gaining access to government oil revenues. In the creeks and oil-producing communities protests erupted over company policies and longstanding grievances over oil spills and company practices, especially employment of local indigenes. All of this was overlaid by a lucrative oil theft business, organized by high ranking military, politicians, and civil servants, in which militant Ijaw youth (the largest and most militant minority group in the Delta) were fighting to get a cut of the illegal “bunkering” trade (that in 2003 siphoned off a staggering 15 percent of national production). Violence across the oil fields prompted all the major oil companies to withdraw their staff, close down operations, and reduce output by more than 750,000 barrels per day (40 percent of the national output). This, in turn, provoked President Obasanjo to dispatch large troop deployment to the oil-producing creeks. In April 2004, another wave of violence erupted around oil installations, this time amid the presence of two militias led by Ateke Tom (the Niger Delta Vigilante) and Alhaji Asari (the Niger Delta People’s Volunteer Force), each driven, and partly funded, by oil monies. By the end of April 2004, Shell alone was losing production of up to 370,000 barrels per day, largely in the Western Delta.

Ten years after the hanging of novelist and minority rights advocate Ken Saro-Wiwa, conditions in the oilfields remain abysmal. An Amnesty International report (2005), entitled “Ten Years On: Injustice and Violence Haunt the Oil Delta,” declared that things have only gotten worse. Security forces still operate with impunity, the government has refused to protect communities in oil producing areas while providing security to the oil industry, and, above all, the oil companies themselves (Shell, Chevron, AGIP, TotalElfFina) bear a share of the responsibility for the appalling misery and the political instability across the region.

The most recent events in Nigeria mark something of a watershed. After taking international oil workers hostage, one of MEND’s demands was the release of two Ijaw leaders. On January 29, 2006 these hostages were released unharmed although the Ijaw leaders in question remained under arrest in Abuja, the Nigerian capital. MEND stated that the release of the hostages was made on “purely humanitarian grounds” and were quoted as saying: “This release does not signify a ceasefire or softening of our position to destroy the oil export capability of the Nigerian government.”

By the first week in February, MEND had contacted the Nigerian press directly, calling for the “international community to evacuate from the Niger Delta by February 12, or ‘face violent attacks.’” Two weeks later, MEND claimed responsibility for attacking a Federal naval vessel and for kidnapping nine workers employed by the oil servicing company Willbros, apparently in retaliation for an attack by the Nigerian military on a community in the Western Delta. The Nigerian government claimed they had attacked barges involved in the contraband oil trade. The geography of the Nigerian Delta, a maze of creeks and swamps, and its marginalization from state transportation and communication infrastructure, make the region extremely difficult to police. This isolation amplifies the significance of MEND’s threats to destroy facilities. Behind these threats is the prospect of attacks on the enormously expensive liquefied natural gas plants in Bonny and another under construction at Escravos. In the days following the violence, the prices of a barrel of oil increased by almost $1.50 and Shell and Chevron indicated that their production in Nigeria had been cut by 15 percent.

ANOTHER COLOMBIA

Nigeria reveals all of the contradictions of the new U.S. energy policy in which African suppliers are expected to play an expanded role. Nigeria is an archetypical “oil nation.” Oil dominates economic and political life. Crude oil production runs currently at more than 2.1 million barrels per day valued at more than $20 billion at 2004 prices. Nigeria’s oil sector now represents a vast domestic industrial infrastructure: more than three hundred oil fields, 5,284 wells, 7,000 kilometers of pipelines, ten export terminals, 275 flow stations, ten gas plants, four refineries, and massive liquefied natural gas (LNG) projects.

A multi-billion dollar oil industry has, however, proved to be a little more than a nightmare. To inventory the ‘achievements’ of Nigerian oil development is a salutary exercise: 85 percent of oil revenues accrue to 1 percent of the population; perhaps $100 billion of $400 billion in revenues since 1970 have simply gone “missing” (The anti-corruption chief Nuhu Ribadu, claimed that in 2003 70 percent of the country’s oil wealth was stolen or wasted; by 2005 it was “only” 40 percent). Between 1965-2004, the per capital income fell from $250 to $212 and income distribution deteriorated markedly over the same period. Between 1970 and 2000 in Nigeria, the number of people subsisting on less than one dollar per day grew from 36 percent to more than 70 percent: from 19 million to a staggering 90 million. According to the IMF, oil “did not seem to add to the standard of living” and “could have contributed to a decline in the standard of living.” Over the last decade GDP per capita and life expectancy have both fallen.

Essentially, petro-development has resulted in the terrifying and catastrophic failure of secular nationalist development. It is sometimes hard to grasp the full consequences and depth of this failure. From the vantage point of the Niger Delta—but no less from the vast slum worlds of Kano or Lagos—development and oil wealth is a cruel joke. These paradoxes and contradictions of oil are nowhere greater than on the oilfields of the Niger Delta. In the oil rich states there is one doctor for every 150,000 inhabitants. “The oil-based economy has wrought only poverty, state violence, and a dying ecosystem,” said Nigerian scholar-activist Ike Okonta. The government’s presence, Okonta says, “is only felt in the form of the machine gun and jackboots.” It is no great surprise that a half century of neglect in the shadow of black gold has made for explosive politics.

Overlaid upon the corrupt Nigerian petro-state, a volatile mix of forces reveal the deadly operations of imperial oil. First, geo-strategic interests in oil employ military and other security forces (including the private security forces and local residents, contracted by the oil companies.) Second, the transnational oil business – the majors, the independents and the vast service industry – are actively involved in the process of local development through new oil company interventions in which the NGO sector and local communities are now drawn into new ‘partnerships.’ Third, multilateral development agencies (the IMF and the IBRD) and financial corpora¬tions like the export credit agencies appear as key “brokers” in the construction and expansion of the energy sectors in oil-producing states. Afterwards, the multilaterals are pressured to become the enforcers of transparency among governments and oil companies.) And not least, there is the relationship between oil and the shady world of drugs, illicit wealth (oil theft for example), mercenaries, and the black economy. This entire oil complex is a sort of corporate enclave economy that is at once violent, unstable, heavily militarized, and largely unaccountable.

The struggle for resource control has taken center stage over the last decade in Nigeria as the Niger Delta has become more volatile. The question is: what is the U.S. prepared to do to keep the oil flowing to feed its addiction? Nigeria is now awash with oil money as the 2007 elections approach, and if the past is any guide, much of this will be deployed to fund political thuggery, intimidation, and outright fraud by the ruling political classes. President Obasanjo is considering a run for a third term – requiring a constitutional amendment – which in turn would be destabilizing in the Muslim north and in the oil producing delta. The increasing U.S. military presence in the Gulf and its anti-terror forces in the north are naturally seen within Nigeria as the price the Bush regime is prepared to pay to keep American cars on the road. An Iraq or Colombia option – civil war and American militarization – cannot be discounted. Blood and oil are never far apart.

Add Your Comments

Latest Comments

Listed below are the latest comments about this post.

These comments are submitted anonymously by website visitors.

TITLE

AUTHOR

DATE

women peace marchers in Warri singing and demonstrating

Sat, May 6, 2006 5:23PM

A Young Nigerian Militant

Sat, May 6, 2006 5:21PM

We are 100% volunteer and depend on your participation to sustain our efforts!

Get Involved

If you'd like to help with maintaining or developing the website, contact us.

Publish

Publish your stories and upcoming events on Indybay.

Topics

More

Search Indybay's Archives

Advanced Search

►

▼

IMC Network