From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

Haiti: Judiciary Independence and the Interim Government

The Independence of the Judiciary in Haiti under the Interim Government

Alex Braden, Brandon Gardner, James Gabello, Ravi K. Reddy*

Alex Braden, Brandon Gardner, James Gabello, Ravi K. Reddy*

University of PittsburgH - School of Law

Center for Internatonal Legal Education - CILE

April 18, 2006

The Independence of the Judiciary in Haiti under the Interim Government

Alex Braden, Brandon Gardner, James Gabello, Ravi K. Reddy*

“We have a culture of impunity in Haiti”, Mario Joseph, Bureau des

Avocats Internationaux (BAI).

Haiti´s judicial system has suffered from a succession of

overbearing Executives, a lack of adequate legal training and

resources, and from the rampant perception that in this impoverished

island nation, justice is only for the rich. Since the 2004 ouster of

the democratically elected government of Jean-Bertrand Aristide,

threats to the judicial independence, both internal and from without,

have only increased under the rule of the interim government of Haiti

(IGH). The IGH has limited the effective functioning of the judiciary

by exerting excessive influence over the judiciary, encouraging

corruption among judges, impeding judicial training, and bringing a

halt to the international community’s reform efforts. This report

examines the failures of the IGH in these areas and considers the

prospects for improvement under René Préval´s incoming administration.

OUTLINE (Click on the links in this outline to jump within the report.)

I. Separation of Powers

A. Executive Selection and Removal in Violation of the

Constitution

B. Other Methods of Illegitimate Executive Pressure -

Effective Removal

II. École de la Magistrature

III. The International Community Relative to the Independence of the

Judiciary

IV. Conclusion

I. Separation of Powers

A. Executive Selection and Removal in Violation of the Constitution

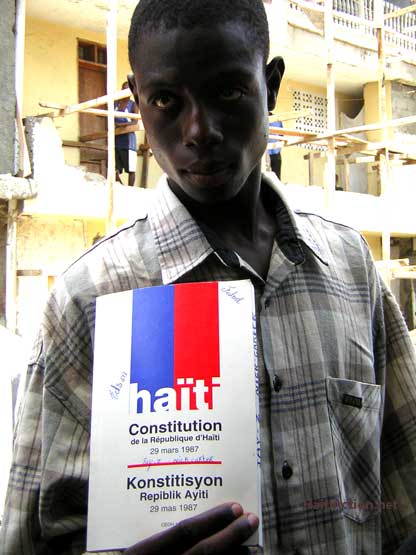

Pursuant to Article 60 of the 1987 Constitution

of Haiti,

the Legislative Branch, the Executive Branch, and the Judicial Branch

of Haiti are independent of one another, and the influence of each

may not extend beyond the boundaries prescribed by the Constitution

and by law.[1] Under the Constitution, Justices of the Cour de

Cassation (Supreme Court) are appointed by the President from a list

submitted by the Senate of three persons per court seat, and are to

be removed only because of a legally determined abuse of authority or

because of permanent physical or mental incapacity.[2] The judges of

the lower courts are also to be appointed by the President, from

lists submitted by the Departmental Assembly or the Communal

Assemblies.[3]

While Haiti has always fostered a “culture of the

Executive”, whereby the President weilds more authority than a

literal reading of the Constitution would provide, the interim

government of Prime Minister Latortue has asserted almost absolute

power in the judicial selection process.[4] Because the Senate has

not functioned since January 2004, the Prime Minister has directly

picked Cour de Cassation Justices without having the three-person

list selected by the Senate as the Constitution provides. The Prime

Minister has also directly selected lower court judges without

reference to the lists of the Departmental Assembly or the Communal

Assemblies.[5] These appointment procedures have had the effect of

de-legitimizing the judicial process as a whole, and the effect has

been most tangibly felt in the rural regions of the country, where

many unqualified Justices of the Peace have been appointed because of

their political ties to Prime Minister Latortue and not because of

the credibility they hold as capable men and women within their

communities. [6]

The most egregious action taken by Prime Minister

Latortue in derogation of his Constitutional authority came in

December 2005, when he removed five of the ten Cour de Cassation

Justices, on the grounds that they were too old.[7] Latortue alleged

neither a legal abuse of authority nor mental incapacity, as required

by the Constitution, nor did he follow constitutional removal

procedures. Rather, Prime Minister Latortue removed the Justices by

executive decree.[8] This illegal action, in violation of the

Constitution, arguably represents the nadir of Executive Branch

interference with the judiciary in Haiti, at least since the new

Constitution was adopted in 1987. [9] In fact, some have suggested

that not even the Duvalier dictatorships would have attempted such an

audacity.[10]

Strangely, this maneuver produced an unexpected result; across the

political spectrum, judges and lawyers joined in protest against this

flagrant executive encroachment on judicial independence. In fact,

Judge Peres-Paul, president of the Haitian Judge’s Association

(L’ANAMAH) and a staunch Aristide opponent who usually deferred to

the positions of Prime Minister Latortue, led the charge in calling

for a judicial strike in retaliation to the Prime Minister’s

action.[11] And even though little came of the judicial strike

itself, there is some reason for optimism. The implication seems to

be that mere politics are no longer enough to keep judges from

fighting for a Judiciary that attempts to check the Executive when it

operates outside its Constitutionally mandated sphere.[12]

Of course, the fact that the Haitian judicial community has

finally begun to fight back gives no comfort to the five removed

Justices. Shortly after their removal, five replacements were

hand-picked by Prime Minister Latortue and appointed through an

illegal procedure.[13] As of the writing of this report, the removed

Justices are pursuing legal challenges to both their removal and to

the illegal appointment of the new Justices. Because their claims

raise important Constitutional questions, however, there is a strong

likelihood that the case will be appealed to the Cour de Cassation,

at which point the new Justices would be forced to recuse themselves

from the case. Then, the remaining Justices (who may be more

sympathetic to the Prime Minister, as he decided not to remove them)

will be forced to decide on the legality of Prime Minister Latortue’s

removal and appointment processes concerning their fellow Justices.

Were this scenario to occur, it is hard to imagine a positive

result, especially given the possible legal and political

ramifications of such a decision. For example, if the Cour de

Cassation rules that the Prime Minister acted lawfully, then the

entire Constitution is called into question, and a dark shadow will

be cast over the entire Judicial branch. If, on the other hand, the

Cour de Cassation finds that the Prime Minister’s activity was

illegal, such a finding could create uncertainty as to whether the

decisions of the illegally appointed Cour de Cassation should be

overturned.

If Haiti’s Constitution is to represent more than a mere collection

of platitudes, it is imperative that President Préval break the cycle

of executive tampering with the judiciary, even though he may have a

Constitutional obligation to remove them all. Good may result from

Haiti’s “culture of the Executive” if President Préval honors his

campaign promise to promote the independence of the Judiciary by

dutifully following the Constitution, his capable stewardship could

set a strong precedent of Haitian accession to the rule of law.[14]

B. Other Methods of Illegitimate Executive Pressure - Effective Removal

Haitian judges remain largely vulnerable to the political,

structural, and cultural pressures that have undermined the judicial

system for decades. For individual judges, these forces often seem

insurmountable. For example, Jean-Sénat Fleury, the judge who oversaw

the much-publicized case of Fr. Gerard Jean-Juste after his first

arrest in 2004, resigned after the Ministry of Justice removed his

caseload.[15] According to Judge Fleury, the Justice Ministry

explained that his caseload was suspended on the basis of complaints

that he was operating too slowly. While the actions of the Minister

of Justice appear to constitute nothing more than bald-faced

retaliation, the particular justification offered is especially

stunning given the fact that Haiti’s prisons are teeming with

prisoners who continue to await trial after years of unconstitutional

incarceration.[16]

Judge Fleury’s resignation illustrates the damaging impact of

baseless executive interference in the operations of the judiciary.

In the first place, the Justice Minister’s decision removed a

competent, independent judge from the bench. Moreover, it served as

a warning to other judges, who will now think twice before making

similar, politically sensitive rulings. As long as the Ministry of

Justice retains the power to micromanage individual judicial dockets,

it retains the power to severely constrain the exercise of an

independent judiciary. In an interview given several months after

his resignation, Judge Fleury observed that “in this system a judge

has two choices. You can accept poverty and humiliation, or you can

accept unemployment.”[17]

Since leaving the bench, Judge Fleury has authored a volume on the

Cour de Cassation and judicial reform in Haiti;[18] however, many

jurists facing the untenable choice he describes have succumbed to

the temptation of a third alternative – corruption. Salaries for

Haitian judges are notoriously low at each level of the judicial

hierarchy, and with literally thousands of detainees languishing in

pre-trial detention, opportunities abound for judges to accept

substantial “grease payments” in exchange for expedited treatment.

It seems that even some of those who have taken principled stands

against Executive Branch interference are not immune to this

phenomenon. At least one well-respected judge interviewed in

preparation of this report stated that after publishing findings of

fact unfavorable to the Justice Ministry, he was arbitrarily

disciplined by the Justice Ministry.[19] The judge remained in his

post, explaining that he could offer more effective resistance by

working within the system. Nevertheless, shortly after giving his

interview, reports emerged that this judge had previously accepted

eighty thousand gourdes[20] from a Port-au-Prince woman to facilitate

the release of her husband from prison.[21]

It seems that the most direct means by which to combat bribery in the

courts requires the effective investigation, prosecution, and

sanctioning of judges who abuse their power for personal financial

gain. At present, however, no such mechanism exists among

self-regulating judicial organizations. Tellingly, the President of

the Haitian Judge’s Association (L’ANAMAH) explained in an interview

that a Code of Ethics for Judges has been promulgated and is in

force, but was unable to find a copy of the Code in his office at the

Palais de Justice.[22] Further, statutory prosecution of corrupt

judges has been wholly lacking, as not a single judge has been

charged under Haitian law with illegally accepting payment for

services rendered.[23] On the other hand, individuals discovered to

have bribed judges are routinely prosecuted. Given the fact that a

few thousand gourdes can mean the difference between freedom and

indefinite detention for their loved ones, this is a calculated risk

that the family members of prisoners are likely to accept.

Beyond eliminating the “culture of impunity” that has long plagued

the Haitian courts, there are methods available to reduce the

incentives for judges to accept bribes.[24] Virtually every recent

report issued on the status of the Haitian judiciary calls for

legislation to raise judges’ salaries to livable levels, and to

provide better material resources such as computers, telephones, and

legal pads.[25] To develop a pay scale and working environment that

affords greater dignity to their vocation, it follows that judges

themselves will be more likely to respect the integrity of the

institution. Further, by lengthening and guaranteeing judicial

mandates at every hierarchical stratum, judges will enjoy a measure

of job security that would help to minimize the inclination exploit

their authority.

While improvement of the infrastructural and remunerative situation

facing judges requires only a proper allocation of money (in Haiti,

more easily said than done), the Latortue administration has only

undermined the ability of judges to attain a sense of security in

their positions. Since assuming power in 2004, the interim

government has proven time and time again that its attitude toward

the judiciary is one of capricious domination. From suspending the

caseloads of judges presiding over politically volatile cases, to

removing Cour de Cassation justices in outright defiance of the

Constitution, the Ministry of Justice has made every effort to

consolidate judicial power in the Executive Branch.[26]

President-elect Préval has a singular opportunity to restore to the

courts the independence and authority granted to them under the

Constitution. To do so, Préval must not give in to the “mentality of

presidentiality” that prevails among Haitian citizens and that has

compelled the nation’s heads of state since the days of the Duvaliers.

When asked whether a Préval administration will reverse the harm done

to the judiciary at the hands of the interim government, nearly every

judge, lawyer, and academic interviewed for this report responded

with hesitant optimism. This “wait and see” attitude is

understandable, given that every historical attempt to consolidate

Haitian democracy has been sabotaged by one faction or another.

Nevertheless, there are significant reasons to expect substantial

improvement once Préval assumes office. In the first place, the

drama surrounding his February election seized the attention of the

international media. While a focus by outsiders on Haitian politics

will naturally subside, this heightened scrutiny will encourage the

incoming administration to maintain a heightened level of

transparency, at least in its early days. Additionally, the fact

that Préval struggled against and overcame the subterfuge of his

opponents appears to have cast an aura of righteous vindication

around his election. Préval received nearly fifty-two percent of the

popular vote, and the fact that his election was ultimately confirmed

with very little subsequent unrest suggests that even those who

opposed him during the campaign are willing to give his government a

chance. Of course, it remains to be seen whether Préval will achieve

anything of consequence before the sabers begin to rattle anew.

II. École de la Magistrature

The Constitution of the Republic of Haiti calls for the creation of a

school of the Magistrature.[27] The creation of a professional

judiciary is one of the most important long-term investments in

Haiti.[28] In 1995, the mandate of the Constitution, with the

assistance of international funding, was fulfilled when the École de

la Magistrature (EMA) was founded.[29] Since the school’s inception

in 1995 approximately 500 judges have been trained.[30] The EMA has not been in operation since 2004 when it was taken over by members of the former military.[31]

According to Mr. Jean Claude Douyon, head of the EMA, negotiations

are currently underway to remove the former military members who are

occupying the school.[32] With an expressed need for well-trained

judges throughout the country, and a need to alleviate the backlog of

cases pending in the judicial system, there is an immediate need for

the EMA to begin operating. In addition to reopening the school, Mr.

Douyon, has proposed that the school begin taking in students on a

continuous basis, regardless of immediate need in the judicial

system.[33] During the period of operation, from 1995 to 2004, the

school produced three classes of judges.[34] His contention is that

if the school operates on a continuous basis, there will always be a

pool of qualified judges to draw from.[35] Mr. Douyon stated that

regardless of the government in power, there is a plan for the

EMA.[36]

Some in Haiti have expressed concerns regarding the ability of the

EMA to produce quality judges. Mr. Léon Saint-Louis, a Port-au-Prince

attorney who has researched the EMA previously, criticized the EMA

for its lack of organization, law, and protocol.[37] He stated that

he believes the quality of judges that were coming out of the school

was higher before. “In the beginning, we had lawyers with much

experience who would accept to become a judge.”[38] He expressed

concern that because students at the EMA are themselves recent

graduates of law school, they lack the practical experience to be

effective judges.[39] While Saint Louis expressed a belief that the

EMA could be reformed, he stated that there must be better

organization if the school is to be effective. Furthermore, he

believes that more experienced candidates need to be recruited.

There is general agreement that the École de la Magistrature can

serve an important function in educating judges, however, without the

commitment of funding and resources to the school no changes will

take place. Even with funding, all speculation on improvements to the

operation of the school remains contingent on the removal of former

military members from its grounds.

III. The International Community Relative to the Independence of the

Judiciary

The view of professors and practitioners and judges is that there are

two prerequisites to judicial reform in Haiti: 1) a democratically

elected government, and 2) assistance from the international

community to apply the system.[40] However, it is believed that too

many conditions are placed on the supply of international aid.[41]

As Mario Joseph of the BAI noted in an earlier interview, the judges

in Haiti are like water in a vase, they will conform to the shape of

their container.[42] As long as the system requires corruption, they

will acquiesce. If, however, the system demands independence,

impartiality, competence, and adherence to the law, they will

likewise comply. Although the international community had many

projects afoot in Haiti during the previous democratic governments

seeking to reform the judiciary, each donor has a distinctly-shaped

container, and the conflicting views and methods coupled with the

uncoordinated nature of international community involvement in Haiti

have resulted in little to no change in the system itself.

Furthermore, many blame the international community itself for

actively kidnapping President Aristide and forcing him into exile[43]

or providing the resources, funding and training for the rebel groups

that overthrew the democratic government of Haiti[44] and financially

strangling the Aristide Administration through withholding IMF and

World Bank funds while forcing Haiti to service the debts.[45] Prior

to the installment of the IGH, evidence of the role of USAID in

Haitian politics was apparent in the role of the International

Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES), a USAID subcontractor, in

intentionally subverting the Aristide government.[46] “They [IFES

workers interviewed by the authors of the University of Miami Report]

further stated that IFES/USAID workers in Haiti want to take credit

for the ouster of Aristide, but cannot ‘out of respect for the wishes

of the U.S. government.’”[47] Although the international community

demanded reform of the judicial and other institutions throughout

this time, it also stands accused of undermining the very democratic

foundation of Haiti.

The National Center for State Courts (NCSC) has operated in Haiti in

conjunction with USAID since August 2004[48]. According to its

website, the operation in Haiti has focused on improving the

performance of the Justice of the Peace (JP) courts in Haiti as 80%

of Haiti’s cases are decided on the JP level.[49] However benign the

intention to reform Haiti’s courts, the NCSC has drawn the ire of

other judicial reform actors as a result of its location, in

Pétionville[50], and because other organizations believe that the

NCSC is hand-feeding the IGH decrees without local input. One

representative of an international organization characterized the

work of the NCSC as such: “Il n’y a pas un échange, c’est un

théâtre.”[51] Another asked where the Haitian identity was in reform

of this kind.[52] Even the mere perception of a bias towards one

political party or ideology will hinder the development of meaningful

judicial reform in Haiti, and sadly, the USAID funded projects have

done just that.

During our recent visit to Haiti, interviews with the UNDP and the

OAS indicated that most of the international community initiatives

meant to promote judicial reform have ceased to operate during the

administration of the Interim Government of Haiti. Exacerbating the

problem further is the fact that there remains a lack of coordination

among the many inter-governmental organizations, the non-governmental organizations, foreign development actors and the Haitian authorities as competing organizations vie for ideological dominance. “It is a war, and here [Haiti] is a front for many ideological battles.”[53] One of the overarching problems remains that the international community’s absence of a clear plan, and the confusion created by competing reform movements, only augments the corruption in Haiti.[54]

The United Nations Development Program’s attempt to inculcate an

independent judiciary in Haiti centers on the use of participatory

democracy to create Haitian ownership of reform through its support

of the Forum Citoyen pour la Réforme de la Justice.[55] The UNDP

representatives we spoke with during our delegation confirmed that

their work, outside the act of promulgating discussion documents,

effectively ground to a halt over the past two years under the IGH.

Until the coup, the OAS Mission in Haiti’s judicial reform component

sent Haitian judges to study the judicial systems of other OAS member

states with an eye to reform. However, instability in Haiti forced

the OAS to suspend the project with the exception of one training

mission to Chile in May of 2004. The focus of the OAS shifted

predominantly to the distribution of electoral cards to facilitate

the elections, a necessary step [as outlined above] for the process

of judicial reform in Haiti. In preparation for the new government,

the OAS judicial reform pillar is “brainstorming” to create a plan

for working with the future government.[56]

IV. Conclusion

An illegitimate executive actively meddles with the constitutional

order, even high-minded judges are bribed with impunity, the EMA is

occupied by the disbanded army, and the international community’s

efforts at judicial reform have been largely suspended. The situation

in Haiti is dire, yet there is hope that the approaching return of

democratic rule will bring with it a renewed respect for the rule of

law and its embodiment in the Haitian Constitution.

Perhaps the most important prospect for positive change once

democracy resumes is in the person of Réne Préval himself. After

all, his upcoming inauguration will mark the beginning of the

President-elect’s second tenure in Palais National. During his

previous term, from 1996 to 2001, Préval displayed a commitment to

the investigation of human rights abuses by government actors, and to

the independent judicial resolution of such issues. Notably,

then-President Préval was the fist, and thus far only, Haitian

president to leave office at the natural expiration of his term.

Dubious though this distinction may be, it does indicate that Préval

has demonstrated respect for Constitutional limits on executive

authority, and that he can successfully resist the trappings and

enticements of presidential power that have so thoroughly possessed

others in his position. Because the problems plaguing the Haitian

legal system are so entrenched and widespread as to have become

virtually institutionalized, a Préval government will certainly have

to struggle mightily to undo these wrongs while operating within

Constitutional strictures. Consequently, any substantial change

achieved through legal means is unlikely to take place overnight.

Nevertheless, to the same extent that Préval must honor the promises

of his campaign while adhering to the laws of his office, the Haitian

citizens who gave him his mandate must also give him the trust and

patience to fulfill it.

* The authors are all law students from the University of Pittsburgh

School of Law and could not have completed this project without the

institutional support of the Bureau des Avocats Internationaux in

Haiti, the assistance of Maren Dobberthein,and Vladimir Laguerre for

translations and scheduling and the generous funding of the

University of Pittsburgh Center for International Legal Education.

[1] Haitian Const. Art. 60, 60-1.

[2] Haitian Const. Art. 175, 177.

[3] Haitian Const. Art 175.

[4] Interview with Supreme Ct Justice Mr. Michel D. Donatien (Mar.

10, 2006).

[5] Interview with Attorney Mario Joseph of the Bureau des Avocats

Internationaux (Mar. 8, 2006).

[6] Id.

[7] Supra, note 4. The official reason for removal was that the

judges were over 60 years old, even though some of of the

replacements were actually older than the removed Justices.

[8] Id. Of course, this official reasoning given that the Justices

were too old to serve was ridiculous; the real reason for their

removal was Prime Minister Latortue’s disapproval with the Justice’s

ruling in a particular case. That case was State v. Simeus, and it

concerned a candidate for President whose eligibility was being

challenged by the CEP (Provisional Election Council) on the grounds

that Mr. Simeus was disqualifed for office due to the fact that he

held U.S. citizenship. According to the 1987 Constitution of Haiti,

Article 135, a candidate for the Haitian presidency must be a

native-born Haitian, never have renounced his/her Haitian

nationality, and have resided in the country for five consecutive

years prior to the election. The Court ruled in favor of Mr. Simeus’

potential candidacy even though Mr. Simeus freely admitted in press

interviews that he had gained U.S. citizenship and that he had a

residence in Texas. In our interview with him, former Justice

Donatien was passionate in defending the legal reasoning underpinning the Court’s decision, which has been roundly criticized. Justice Donatien went into great technical detail to explain that the CEP had not made an adequate showing as a matter of law that Simeus had

obtained U.S. citizenship. Further, Justice Donatien argued that

there is a legal difference between having Haitian and U.S.

citizenship and renouncing Haitian citizenship in favor of becoming a

U.S. Citizen. Additionally, Justice Donatien pointed to a 1984 Law

on Publication, Article 30 of which mandated that no Haitian national

could lose their citizenship without that information being printed

in the Official Journal, which was not done in the case of Mr.

Simeus. Finally, Justice Donatien questioned whether the provisions

of the Constitution, which would seemingly bar Mr. Simeus’ candidacy,

could be applied retroactively to someone born prior to its adoption

so as to deny him proper Haitian citizenship.

[9] William P. Quigley, The Absence of An Independent Judiciary in

Haiti, Human Rights Report, Draft of 12/12/2005.

[10] Supra, note 5.

[11] Interview with Judge Jean Peres-Paul, President of L’ANAMAH

(Mar. 08, 2006).

[12] Every one of the eight judges and lawyers, who represented a

wide spectrum of political viewpoints that spoke to us about the

removal of the Cour de Cassation Justices, were in total agreement

that the Prime Minister’s act was unconstitutional.

[13] For example, the new Justices were sworn in before there was

official publication of their nominations, as required by the

Presidential Decree of 8/22/1995, On the Organization of Judges.

Also, the Justices were sworn in at the Ministry of Justice and not

in public, which also was a violation of the law.

[14] Interview with Chantal Thériault, Chef du Pilier Justice, OAS

(Mar. 10, 2006). Ms. Thériault observed that this very idea was part

of the platform that President-elect Préval ran on during his

Presidential campaign, and that during his first Presidential term

from 1996-2001 Préval had established a good record of respecting

judicial independence.

[15] See Brian Concannon, Jr., An Prensip: The Subordination of the

Haitian Judiciary May 12, 2005.

[16] Haitian Const, Art. 26. Art. 26 provides: “No one may be kept

under arrest more than forty-eight (48) hours unless he has appeared

before a judge asked to rule on the legality of the arrest and the

judge has confirmed the arrest by a well-founded decision.”

Interview with Gervais Charles, head of the Bar Association of

Port-au-Prince (Mar. 7, 2006). Mr. Charles indicated that

Port-au-Prince currently houses over 2000 prisoners, many hundreds of

which have never seen a judge.

[17] Interview with Judge Jean-Sénat Fleury (Mar. 7, 2006).

[18] Cour de Cassation en Face de la Reforme Judicial en Haiti.

[19] The name of this prominent judge has been withheld so as not to

incriminate the individual who paid him a bribe.

[20] Roughly equivalent to $2,000 U.S.

[21] The woman, whose husband was arrested and jailed on allegations

of being a Lavalas (pro-Aristide) street-leader, is an outspoken

activist against the illegal detention of Haitian citizens. In 2004,

she bribed the judge in question, seeking to expedite her husband’s

release. The woman’s husband still remains imprisoned as of March,

2006.

[22] Supra, note 11.

[23] Interview with Léon Saint-Louis, Port-au-Prince human rights

attorney (Mar. 10, 2006).

[24] Interview with Renan Hedouville, Secretary General of Comité des

Avocats pour le Respect des Libertés Individuelles (Mar 10, 2006).

[25] See, e.g. Organization of American States Inter-American

Commision on Human Rights report, Haiti: Failed Justice or the Rule

of Law? Challenges Ahead for Haiti and the International Community,

Oct. 26, 2005, at 59-60.

[26] Supra n. 15.

[27] Haitian Const., Art. 176.

[28] Haiti Democracy Project, The Restoration of Democracy and

Justice. Available at

<http://www.haitipolicy.org/archives/Sept-Nov2001/part2.htm>

[29] Interview with Jean Claude F. Douyon, Director of the École de

la Magistrature (EMA), (Mar. 9, 2006). Mr. Douyan indicated that the

EMA is primarily funded by the governments of France and Canada.

[30] France and Haiti– Cultural, scientific and technical

cooperation, Ministere des Affaires etrangeres,

<http://tinyurl.com/foc8n>

[31] Interview with Judges Jean-Sénat Fleury and Brédy Fabien (Mar.

7, 2006).

[32] Supra, n. 29.

[33] Id. According to Mr. Douyon, the EMA currently admits students

only at the need of the Ministry of Justice.

[34] Supra, n. 28.

[35] Supra, n. 29.

[36] Id.

[37] Supra, n. 23.

[38] Id.

[39] Id.

[40] Interview with Professor Josué Pierre-Louis, Doyon Université

Quisqueya, Faculté de Droit (Mar. 9, 2006).

[41] Id.

[42] Supra, n. 4.

[43] IJDH, BAI, Yale Law School and TransAfrica Petition to the

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights Against U.S., Haiti and

Dominican Republic for Overthrowing Haiti's Democracy, available at:

<http://www.ijdh.org/articles/article_iachr_2-1-06.htm>, Amy Wilentz,

Coup in Haiti, The Nation March 4, 2004, available at:

<http://www.thenation.com/doc/20040322/wilentz>

[44] <http://www.law.miami.edu/cshr/CSHR_Report_02082005_v2.pdf>

20-24. See also: IJDH, BAI, Yale Law School and TransAfrica Petition

to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights Against U.S., Haiti

and Dominican Republic for Overthrowing Haiti's Democracy, supra n..

43,

[45] Nicolas Rossier, Aristide and the Endless Revolution, Film (2005).

[46] <http://www.law.miami.edu/cshr/CSHR_Report_02082005_v2.pdf, 20-22>.

[47] <http://www.law.miami.edu/cshr/CSHR_Report_02082005_v2.pdf>, 22.

[48]

<http://ipd.ncsconline.org/ncsc/main.aspx?

dbID=DB_LatinAmericaandCarribean296#hai>

[49] Id.

[50] A relatively affluent suburb of Port-au-Prince.

[51] Interview with Guilaine Moinerie, Conseillère Technique UNDP

Haïti (Mar. 10, 2006).

[52] Interview with Gracia Joseph S. Maxi, Expert National UNDP Haïti

(Mar. 10, 2006).

[53] Supra, n. 51. See Also, Walt Bogdanich and Jenny Nordberg, Mixed

U.S. Signals Helped Tilt Haiti Toward Chaos, New York Times, January

29, 2006, available at: <http://tinyurl.com/hoxoh>

(Outlining the

conflicting messages coming from the United States, one, the

‘official’ policy from the embassy and the conflicting policy from

the International Republican Institute which claimed to be the real

voice of Bush Administration policy in Haiti.).

[54] Supra, n. 14.

[55] <http://www.forumcitoyen.org.ht>,

<http://www.undp.org/surf-panama/docs/cso.doc>

[56] Supra, n. 14

For more information:

http://www.law.pitt.edu/academics/programs...

Add Your Comments

We are 100% volunteer and depend on your participation to sustain our efforts!

Get Involved

If you'd like to help with maintaining or developing the website, contact us.

Publish

Publish your stories and upcoming events on Indybay.

Topics

More

Search Indybay's Archives

Advanced Search

►

▼

IMC Network