From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

What's Good for GM...On the State of the U.S. Economy

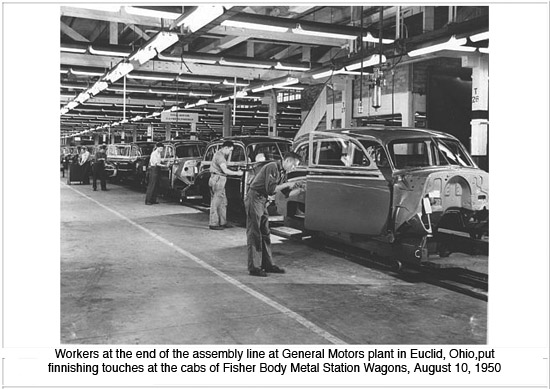

When Standard & Poor’s credit raters gave thumbs down to General Motors and Ford on May 5th, the once mighty U.S. auto companies tumbled from investment grade to junk bond status. Mainstream folk wisdom once proclaimed, “What’s good for GM is good for the country,” but that aphorism came from the 1950s, during the long post-WWII “golden age,” when U.S. capitalism was on the rise, and the standard of living for U.S. workers improved year after year. That long economic boom ended with the oil shocks and stagflation of the 1970s. So now, in 2005, what does the “junking” of GM and Ford reveal about the health of the U.S. economy?

When Standard & Poor’s credit raters gave thumbs down to General Motors and Ford on May 5th, the once mighty U.S. auto companies tumbled from investment grade to junk bond status. Mainstream folk wisdom once proclaimed, “What’s good for GM is good for the country,” but that aphorism came from the 1950s, during the long post-WWII “golden age,” when U.S. capitalism was on the rise, and the standard of living for U.S. workers improved year after year. That long economic boom ended with the oil shocks and stagflation of the 1970s. So now, in 2005, what does the “junking” of GM and Ford reveal about the health of the U.S. economy?

First of all, the globalization of production and finance since World War II means we can’t assess the health of the U.S. economy without considering its status in the global economy. The downgrading of GM and Ford represents shifts in the auto industry with international repe-cussions. In April, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) alluded to GM’s status in its semi-annual Global Financial Stability Report, cautioning that “a downgrading of a major global company to subinvestment grade for reasons that may not be linked to negative events in the global economy” could lead to international financial turbulence. According to the report, the proliferation of credit derivatives in recent years — which facilitates the transfer of risk without transferring the underlying asset — creates the risk that investors might “rush to exit at the same time, leading to market liquidity shortages.”

Also in April, Reagan-era Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker published an article in the Washington Post in which he expressed concern that a declining U.S. dollar combined with an increased risk of volatility in global financial markets could lead to the sort of stagflation that plagued the U.S. economy in the 1970s, with “a volatile and depressed dollar, inflationary pressures, a sudden increase in interest rates and a couple of big recessions.” Present Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan chimed in on the day of GM’s and Ford’s devaluation, “Rapid growth in the credit derivatives markets has created considerable uncertainty about how the global financial system might react to any new economic shocks.” If huge companies like GM and Ford are now considered too risky for investment, and in fact might provoke crises in the global market, what does all this volatility tell us about the health of the US economy?

Former Federal Reserve economist Christopher Rude, now at York University in Toronto, put it in stark terms when we spoke on Monday May 9th, “The U.S. economy is being ‘hollowed out’ for the sake of U.S. capital.” Mr. Rude distinguished sharply between the outlook for labor in the U.S. economy and the outlook for U.S. capital. “The strength of U.S. capital, and hence of the U.S. state, is both larger and stronger than the U.S. domestic economy. The U.S. population is being sacrificed on the altar of global capitalism, and yet that global capitalism needs the demand that the U.S. population generates.”

Consider for a moment that the downgrading of GM and Ford—part of the “hollowing out” of the US economy—might have a silver lining for the firms themselves. Read any mainstream article on GM’s predicament and you’ll discover that what’s considered good for GM these days is getting rid of its “legacy” costs, corporate jargon for the healthcare benefits and pensions negotiated in its last contract with the United Auto Workers (UAW). A good example of this sort of spin comes from Washington Post columnist George Will, for one, who compared GM’s imminent fall in his May 1st column to the crumbling of an overburdened welfare state. If GM and Ford find a way to jettison their “legacy” through Chapter 11 bankruptcy and by pressuring their labor forces into accepting severe cuts in benefits, the present junk bond status may well have a silver lining. An Economist article from May 6th entitled “Two Piles of Junk?” concludes, “…the opportunity to emerge from Chapter 11 as smaller, leaner operations, stripped of some burdensome liabilities and better equipped to move back into the fast lane of carmaking, may be starting to look like an appealing option.”

Restructuring under Chapter 11 wouldn’t solve all of GM’s and Ford’s problems, though, because they would still face a loss of market share to Asian auto manufacturers and the effects of historically high oil and gas prices. I emailed former Canadian Auto Worker’s Union (CAW) Research Director Sam Gindin about the outfall from Standard & Poor’s announcement, and he had this to say, “Workers are not responsible for GM’s problems.” He characterized the pressures on the U.S. auto industry, which will be deflected as much as possible onto its labor force, as the cost of privatizing what remains of the U.S. welfare state. “In the short run,” he wrote, “GM is not about to disappear, but it will start downsizing and try to set the stage for workers lowering their benefits and increasing their co-pays. For GM this is both a crisis and an opportunity to solve some longer-term ‘problems.’”

Regarding labor’s potential response to the pending cutbacks—GM’s contract with the UAW expires in 2007—Mr. Gindin said, “This would seem to open the door to stressing the importance of a national healthcare plan which progressives should want on its own merits but which is also functional to GM in its competition with other auto manufacturers, who either have such costs covered at home or have lower costs in the U.S. because of demographics.”

It is true that a national healthcare system in the U.S. would, at least temporarily, benefit both workers and firms like GM and Ford. A source in the labor movement who wished to remain anonymous suggested that this topic has already come up behind closed doors at GM. But the likelihood of winning such a concession from the present administration is less than zero, and neither GM nor Ford would want to be associated with such a campaign anyway for fear of a political and economic backlash.

If the downgrading of GM and Ford yields any insight into the present state of the U.S. economy, it is that the rules and outcomes for capital are dramatically different than those for labor. If a GM or a Ford Motors goes bankrupt, they restructure and capital ultimately grows stronger. If you or I go bankrupt—for instance, due to unpayable medical debt, a scenario that’s increasingly likely under the Bush administration’s bankruptcy “reforms,”—we would be lucky to avoid financial ruin. Unrelenting pressure to privatize the last vestiges of the U.S. welfare state continues to translate into attacks on our health and security. It seems what’s good for GM is not so good for the working class and the poor.

GM TUMBLES: But How Far?

Let’s consider just how far General Motors has fallen. In the 1940s GM led the country’s war production effort. By the 1950s GM had grown into the largest corporation in the US in terms of revenue as a percentage of GDP. It’s corporate strength was so great that the president of GM during this period, Charles Wilson, also played a major political role, first as director of the War Production Board and then as Secretary of Defense under Eisenhower. In fact it was during Wilson’s Senate confirmation hearings that he unwittingly spawned the folk wisdom, “What’s good for GM is good for the country.” In response to questioning about the potential for a conflict of interest between his allegiance to GM—in which he tried to retain ownership of $2.5 million in stock—and his duty to the nation, he responded, “… for years I thought what was good for the country was good for General Motors and vice versa.”

Sara Burke is co-editor of Gloves Off http://www.glovesoff.org

First of all, the globalization of production and finance since World War II means we can’t assess the health of the U.S. economy without considering its status in the global economy. The downgrading of GM and Ford represents shifts in the auto industry with international repe-cussions. In April, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) alluded to GM’s status in its semi-annual Global Financial Stability Report, cautioning that “a downgrading of a major global company to subinvestment grade for reasons that may not be linked to negative events in the global economy” could lead to international financial turbulence. According to the report, the proliferation of credit derivatives in recent years — which facilitates the transfer of risk without transferring the underlying asset — creates the risk that investors might “rush to exit at the same time, leading to market liquidity shortages.”

Also in April, Reagan-era Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker published an article in the Washington Post in which he expressed concern that a declining U.S. dollar combined with an increased risk of volatility in global financial markets could lead to the sort of stagflation that plagued the U.S. economy in the 1970s, with “a volatile and depressed dollar, inflationary pressures, a sudden increase in interest rates and a couple of big recessions.” Present Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan chimed in on the day of GM’s and Ford’s devaluation, “Rapid growth in the credit derivatives markets has created considerable uncertainty about how the global financial system might react to any new economic shocks.” If huge companies like GM and Ford are now considered too risky for investment, and in fact might provoke crises in the global market, what does all this volatility tell us about the health of the US economy?

Former Federal Reserve economist Christopher Rude, now at York University in Toronto, put it in stark terms when we spoke on Monday May 9th, “The U.S. economy is being ‘hollowed out’ for the sake of U.S. capital.” Mr. Rude distinguished sharply between the outlook for labor in the U.S. economy and the outlook for U.S. capital. “The strength of U.S. capital, and hence of the U.S. state, is both larger and stronger than the U.S. domestic economy. The U.S. population is being sacrificed on the altar of global capitalism, and yet that global capitalism needs the demand that the U.S. population generates.”

Consider for a moment that the downgrading of GM and Ford—part of the “hollowing out” of the US economy—might have a silver lining for the firms themselves. Read any mainstream article on GM’s predicament and you’ll discover that what’s considered good for GM these days is getting rid of its “legacy” costs, corporate jargon for the healthcare benefits and pensions negotiated in its last contract with the United Auto Workers (UAW). A good example of this sort of spin comes from Washington Post columnist George Will, for one, who compared GM’s imminent fall in his May 1st column to the crumbling of an overburdened welfare state. If GM and Ford find a way to jettison their “legacy” through Chapter 11 bankruptcy and by pressuring their labor forces into accepting severe cuts in benefits, the present junk bond status may well have a silver lining. An Economist article from May 6th entitled “Two Piles of Junk?” concludes, “…the opportunity to emerge from Chapter 11 as smaller, leaner operations, stripped of some burdensome liabilities and better equipped to move back into the fast lane of carmaking, may be starting to look like an appealing option.”

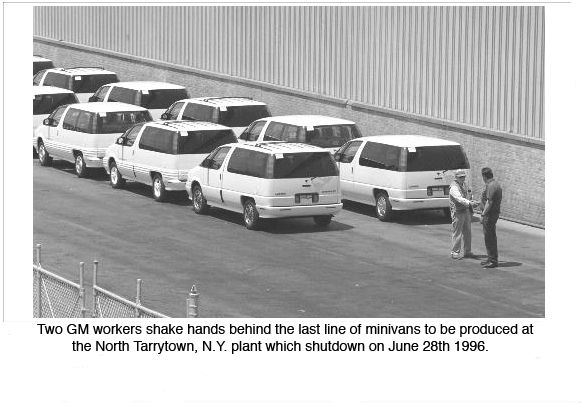

Restructuring under Chapter 11 wouldn’t solve all of GM’s and Ford’s problems, though, because they would still face a loss of market share to Asian auto manufacturers and the effects of historically high oil and gas prices. I emailed former Canadian Auto Worker’s Union (CAW) Research Director Sam Gindin about the outfall from Standard & Poor’s announcement, and he had this to say, “Workers are not responsible for GM’s problems.” He characterized the pressures on the U.S. auto industry, which will be deflected as much as possible onto its labor force, as the cost of privatizing what remains of the U.S. welfare state. “In the short run,” he wrote, “GM is not about to disappear, but it will start downsizing and try to set the stage for workers lowering their benefits and increasing their co-pays. For GM this is both a crisis and an opportunity to solve some longer-term ‘problems.’”

Regarding labor’s potential response to the pending cutbacks—GM’s contract with the UAW expires in 2007—Mr. Gindin said, “This would seem to open the door to stressing the importance of a national healthcare plan which progressives should want on its own merits but which is also functional to GM in its competition with other auto manufacturers, who either have such costs covered at home or have lower costs in the U.S. because of demographics.”

It is true that a national healthcare system in the U.S. would, at least temporarily, benefit both workers and firms like GM and Ford. A source in the labor movement who wished to remain anonymous suggested that this topic has already come up behind closed doors at GM. But the likelihood of winning such a concession from the present administration is less than zero, and neither GM nor Ford would want to be associated with such a campaign anyway for fear of a political and economic backlash.

If the downgrading of GM and Ford yields any insight into the present state of the U.S. economy, it is that the rules and outcomes for capital are dramatically different than those for labor. If a GM or a Ford Motors goes bankrupt, they restructure and capital ultimately grows stronger. If you or I go bankrupt—for instance, due to unpayable medical debt, a scenario that’s increasingly likely under the Bush administration’s bankruptcy “reforms,”—we would be lucky to avoid financial ruin. Unrelenting pressure to privatize the last vestiges of the U.S. welfare state continues to translate into attacks on our health and security. It seems what’s good for GM is not so good for the working class and the poor.

GM TUMBLES: But How Far?

Let’s consider just how far General Motors has fallen. In the 1940s GM led the country’s war production effort. By the 1950s GM had grown into the largest corporation in the US in terms of revenue as a percentage of GDP. It’s corporate strength was so great that the president of GM during this period, Charles Wilson, also played a major political role, first as director of the War Production Board and then as Secretary of Defense under Eisenhower. In fact it was during Wilson’s Senate confirmation hearings that he unwittingly spawned the folk wisdom, “What’s good for GM is good for the country.” In response to questioning about the potential for a conflict of interest between his allegiance to GM—in which he tried to retain ownership of $2.5 million in stock—and his duty to the nation, he responded, “… for years I thought what was good for the country was good for General Motors and vice versa.”

Sara Burke is co-editor of Gloves Off http://www.glovesoff.org

Add Your Comments

We are 100% volunteer and depend on your participation to sustain our efforts!

Get Involved

If you'd like to help with maintaining or developing the website, contact us.

Publish

Publish your stories and upcoming events on Indybay.

Topics

More

Search Indybay's Archives

Advanced Search

►

▼

IMC Network