From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

36th Anniversary of Israel's Attack on the USS Liberty

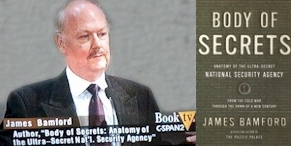

On June 8, 1967 the State of Israel ruthlessly attacked the US ship USS Liberty for over 2 hours in a combined air/sea operation during the Israeli's pre-emptive 1967 rout of the Arabs (this was the year the West Bank was first occupied by Israel). The incident, which cost 34 American lives was hushed up and never investigated by a Israeli occupied US Congress. Bamford's recent book 'Body of Secrets' looks at the incident with new information from the files of National Security Council and NSC staff interviews. The seventh chapter 'Blood' deals with the USS Liberty attack. At the end, the statement of Admiral Thomas Moorer, former Head, Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Link on this page for the NYT bestselling book, Body of Secrets:

http://www.ussliberty.org/

BODY OF SECRETS

JAMES BAMFORD

Anatomy of the Ultra-Secret National Security Agency from the Cold War through a New Century

Doubleday New york London Toronto Sydney Auckland

________________________________________________________________________________________________

PUBLISHED BY DOUBLEDAY

A division of Random House, Inc.

1540 Broadway, New York, New York 10056

DOUBLEDAY and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are

trademarks of Doubleday, a division of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bamford, James,

Body of secrets: anatomy of the ultra-secret National Security Agency:

from the Cold War through the dawn of a new century /

James Bamford.—1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. United States. National Security Agency—History. 2. Electronic

intelligence—United States—History. 3. Cryptography—United

States—History. I. Title.

UB256.U6 B56 2001

527.1273—dc21

00-058920

ISBN 0-585-49907-8

Book design by Maria Carella

Copyright © 2001 by James Bamford

All Rights Reserved

Printed in the United States of America

May 2001

First Edition

15579 10 8642

_______________________________________________________________________________________

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My most sincere thanks to the many people who helped bring Body of

Secrets to life. Lieutenant General Michael V. Hayden, NSA's director,

had the courage to open the agency's door a crack. Major General John

E. Morrison (Retired), the dean of the U.S. intelligence community, was

always gracious and accommodating in pointing me in the right direc-

tions. Deborah Price suffered through my endless Freedom of Informa-

tion Act requests with professionalism and good humor. Judith Emmel

and Colleen Garrett helped guide me through the labyrinths of Crypto

City. Jack Ingram, Dr. David Hatch, Jennifer Wilcox, and Rowena

Clough of NSA's National Cryptologic Museum provided endless help in

researching the agency's past.

Critical was the help of those who fought on the front lines of the

cryptologic wars, including George A. Cassidy, Richard G. Schmucker,

Marvin Nowicki, John Arnold, Harry 0. Rakfeldt, David Parks, John

Mastro, Wayne Madsen, Aubrey Rrown, John R. DeChene, Bryce Lock-

wood, Richard McCarthy, Don McClarren, Stuart Russell, Richard E.

Kerr, Jr., James Miller, and many others. My grateful appreciation to all

those named and unnamed.

Thanks also to David J. Haight and Dwight E. Strandberg of the

Dwight D. Elsenhower Presidential Library and to Thomas E. Samoluk

of the U.S. Assassinations Records Review Board.

Finally I would like to thank those who helped give birth to Body

of Secrets, including Kris Dahl, my agent at International Creative

Management; Shawn Coyne, my editor at Doubleday; and Bill Thomas,

Bette Alexander, Jolanta Benal, Lauren Field, Chris Min, Timothy Hsu,

and Sean Desmond.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Chapter Seven - BLOOD

For four years NSA's "African Queen" lumbered inconspicuously up and

down the wild and troubled East African coast with the speed of an old

sea turtle. By the spring of 1967, the tropical waters had so encrusted her

bottom with sea life that her top speed was down to between three and

five knots. With Che Guevara long since gone back to Cuba, NSA's G

Group, responsible for the non-Communist portion of the planet, de-

cided to finally relieve the Valdez and send her back to Norfolk, where

she could be beached and scraped.

It was also decided to take maximum advantage of the situation by

bringing the ship home through the Suez Canal, mapping and charting

the radio spectrum as she crawled slowly past the Middle East and the

eastern Mediterranean. "Now, frankly," recalled Frank Raven, former

chief of G Group, "we didn't think at that point that it was highly de-

sirable to have a ship right in the Middle East; it would be too explosive

a situation. But the Valdez, obviously coming home with a foul bottom

and pulling no bones about it and being a civilian ship, could get away

with it." It took the ship about six weeks to come up through the canal

and limp down the North African coast past Israel, Egypt, and Libya.

About that same time, the Valdez's African partner, the USS Lib-

erty, was arriving off West Africa, following a stormy Atlantic crossing,

for the start of its fifth patrol. Navy Commander William L. McGona-

gle, its newest captain, ordered the speed reduced to four knots, the low-

est speed at which the Liberty could easily answer its rudder, and the

ship began its slow crawl south. On May 22, the Liberty pulled into

Abidjan, capital of the Ivory Coast, for a four-day port call.

Half the earth away, behind cipher-locked doors at NSA, the talk

was not of possible African coups but of potential Middle East wars. The

indications had been growing for weeks, like swells before a storm. On

the Israeli-Syrian border, what started out as potshots at tractors had

quickly escalated to cannon fire between tanks. On May 17, Egypt (then

known as the United Arab Republic [UAR]) evicted UN peacekeepers

and then moved troops to its Sinai border with Israel. A few days later,

Israeli tanks were reported on the Sinai frontier, and the following day

Egypt ordered mobilization of 100,000 armed reserves. On May 25,

Gamal Abdel Nasser blockaded the Strait of Tiran, thereby closing the

Gulf of Aqaba to Israeli shipping and prohibiting unescorted tankers

under any flag from reaching the Israeli port of Elat. The Israelis de-

clared the action "an act of aggression against Israel" and began a full-

scale mobilization.

As NSA's ears strained for information, Israeli officials began ar-

riving in Washington. Nasser, they said, was about to launch a lopsided

war against them and they needed American support. It was a lie. In

fact, as Menachem Begin admitted years later, it was Israel that was

planning a first strike attack on Egypt. "We . . . had a choice," Begin

said in 1982, when he was Israel's prime minister. "The Egyptian army

concentrations in the Sinai approaches do not prove that Nasser was re-

ally about to attack us. We must be honest with ourselves. We decided to

attack him."

Had Israel brought the United States into a first-strike war against

Egypt and the Arab world, the results might have been calamitous. The

USSR would almost certainly have gone to the defense of its Arab

friends, leading to a direct battlefield confrontation between U.S. and

Soviet forces. Such a dangerous prospect could have touched off a nu-

clear war.

With the growing possibility of U.S. involvement in a Middle East

war, the Joint Chiefs of Staff needed rapid intelligence on the ground

situation in Egypt. Above all, they wanted to know how many Soviet

troops, if any, were currently in Egypt and what kinds of weapons they

had. Also, if U.S. fighter planes were to enter the conflict, it was essen-

tial to pinpoint the locations of surface-to-air missile batteries. If troops

went in, it would be vital to know the locations and strength of oppos-

ing forces.

Under the gun to provide answers, officials at NSA considered

their options. Land-based stations, like the one in Cyprus, were too far

away to collect the narrow line-of-sight signals used by air defense radar,

fire control radar, microwave communications, and other targets.

Airborne Sigint platforms—Air Force C-150s and Navy EC-121s—

could collect some of this. But after allowing for time to and from the

"orbit areas," the aircrews would only have about five hours on sta-

tion—too short a time for the sustained collection that was required.

Adding aircraft was also an option but finding extra signals intelligence

planes would be very difficult. Also, downtime and maintenance on

those aircraft was greater than for any other kind of platform.

Finally there were the ships, which was the best option. Because

they could sail relatively close, they could pick up the most important

signals. Also, unlike the aircraft, they could remain on station for weeks

at a time, eavesdropping, locating transmitters, and analyzing the intel-

ligence. At the time, the USS Oxford, and Jamestown were in Southeast

Asia; the USS Georgetown and Belmont were eavesdropping off South

America; and the USNS Muller was monitoring signals off Cuba. That

left the USNS Faldez and the USS Liberty. The Valdez. had just com-

pleted a long mission and was near Gibraltar on its way back to the

United States. On the other hand, the Liberty, which was larger and

faster, had just begun a new mission and was relatively close, in port in

Abidjan.

Several months before, seeing the swells forming, NSA's G Group

had drawn up a contingency plan. It would position the Liberty in the

area of "LOLO" (longitude 0, latitude 0) in Africa's Gulf of Guinea, con-

centrating on targets in that area, but actually positioning her far

enough north that she could make a dash for the Middle East should the

need arise. Despite the advantages, not everyone agreed on the plan.

Frank Raven, the G Group chief, argued that it was too risky. "The ship

will be defenseless out there," he insisted. "If war breaks out, she'll be

alone and vulnerable. Either side might start shooting at her. ... I say

the ship should be left where it is." But he was overruled.

On May 25, having decided to send the Liberty to the Middle East,

G Group officials notified John Connell, NSA's man at the Joint Recon-

naissance Center. A unit within the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the JRC was

responsible for coordinating air, sea, and undersea reconnaissance

operations. At 8:20 that spring evening, amid the noisy clatter of tele-

type machines, a technician tapped out a brief Flash message to the

Liberty:

MAKE IMMEDIATE PREPARATIONS TO GET UNDER-

WAY. WHEN READY FOR SEA ASAP DEPART PORT

ARIDJAN AND PROCEED REST POSSIRLE SPEED TO

ROTA SPAIN TO LOAD TECHNICAL SUPPORT MATE-

RIAL AND SUPPLIES. WHEN READY FOR SEA PRO-

CEED TO OPERATING AREA OFF PORT SAID.

SPECIFIC AREAS WILL FOLLOW.

In the coal-black Ivoirian night, an island of light lit up the end of the

long wooden pier where the USS Liberty lay docked. Reyond, in the har-

bor, small dots of red and green blinked like Christmas-tree lights as

hulking cargo ships slowly twisted with the gentle tide.

It was around 5:45 A.M. when Lieutenant Jim O'Connor woke to a

knock on his stateroom door. The duty officer squinted as he read the

message in the red glow of an emergency light. Still half asleep, he

mumbled a curse and quickly threw on his trousers. "It was a message

from the Joint Chiefs of Staff," O'Connor recalled telling his cabinmate.

"Whoever heard of JCS taking direct control of a ship?" Within minutes

reveille sounded and the Liberty began to shudder to life. Less than

three hours later, the modern skyline of Abidjan disappeared over the

stern as the ship departed Africa for the last time. Silhouetted against

the rising sun was the large moon-bounce antenna on the rear deck,

pointing straight up as if praying.

For eight days, at top speed, the bow cut a silvery path through

5,000 miles of choppy Atlantic Ocean. The need for linguists was espe-

cially critical on the Liberty, which, because of her West African targets,

carried only French and Portuguese language experts. Therefore, five

Arabic linguists—two enlisted Marines and three NSA civilians—were

ordered to Rota to rendezvous with the Liberty. Although the ship al-

ready had numerous Russian linguists, it was also decided to add one

more, a senior analytical specialist.

NSA had originally wanted to also put Hebrew linguists on the

ship, but the agency just didn't have enough. "I mean, my God," said

Frank Raven, "you're manning a crisis; where are you going to get these

linguists from? You go out and ask the nearest synagogue? We got to-

gether every linguist we could manage and we not only sent them to

Rota but then we have to back up every military station in the Middle

East—we're sending them into Athens, we're sending them into

Turkey—by God, if you can speak Arabic and you're in NSA you're on

a plane!"

As the Liberty steamed northward, Marine Sergeant Bryce Lock-

wood was strapped in a signals intelligence plane flying 50,000 feet

above the frigid Norwegian Sea off Iceland. Lockwood was an experi-

enced signals intelligence intercept operator and Russian linguist; he

and his crewmembers were shadowing the Russian Northern Fleet as it

conducted summer war games. But the ferret operation had been

plagued with problems. A number of the missions had been canceled as

a result of aircraft equipment failures and the one Lockwood was on in-

tercepted only about three minutes of Russian voice, which was so gar-

bled that no one could understand it.

During the operation, Lockwood was temporarily assigned to the

U.S. Navy air base at Keflavik, Iceland. But as the Russian exercise

came to an end, he headed back to his home base, the sprawling Navy

listening post at Bremerhaven, where he specialized in analyzing inter-

cepted Russian communications. The plane flew first to Rota, where he

was to catch another military flight back to Germany. However, be-

cause it was the Memorial Day weekend, few U.S. military flights were

taking off; he was forced to spend the night. That afternoon Lockwood

went to a picnic, had a few beers, and then went to bed early in his

quarters.

About 2:00 A.M. he was suddenly woken up by some loud pounding

on his door. Assuming it was just a few of his fellow Marines wanting to

party, he pulled the cover over his head and ignored it. But the banging

only got louder. Now angry, Lockwood finally threw open the door.

Standing in front of him in the dim light was a sailor from the duty of-

fice. "I have a message with your name on it from the Joint Chiefs of

Staff," he said somewhat quizzically. "You're assigned to ]oin the USS

Liberty at 0600 hours. You better get up and pack your seabag." It was a

highly unusual order, a personal message from the JCS at two in the

morning; Lockwood had little time to ponder it.

It was just an hour or so after dawn on the first of June when the

Liberty slid alongside a pier in Rota. Already waiting for them were

Lockwood and the five Arabic linguists. A short time later, thick black

hoses, like boa constrictors, disgorged 580,000 gallons of fuel into the

ship's tanks while perspiring sailors in dungarees struggled to load crates

of vegetables and other food. Several technicians also retrieved boxes of

double-wrapped packages and brought them aboard. The packages con-

tained supersensitive signals intelligence data left for them by the

Valdez as she passed through Rota on the way back to Norfolk. Included

were critical details on Middle East communication patterns picked up

as the Valdez transited the area: "who was communicating on what

links—Teletype, telephone, microwave, you name it," said Raven.

As she steamed west across the Mediterranean to Rota, the Valdez

had also conducted "hearability studies" for NSA in order to help deter-

mine the best places from which to eavesdrop. Off the eastern end of

Crete, the Valdez discovered what amounted to a "duct" in the air, a sort

of aural pipeline that led straight to the Middle East. "You can sit in

Crete and watch the Cairo television shows," said Raven. "If you're over

flat water, basically calm water, the communications are wonderful." He

decided to park the Liberty there.

Rut the Joint Chiefs of Staff had other ideas. In Rota, Commander

McGonagle received orders to deploy just off the coasts of Israel and

Egypt but not to approach closer than twelve and a half nautical miles

to Egypt or six and a half to Israel. Following some repairs to the trou-

blesome dish antenna, the Liberty cast off from Rota just after noon on

June 2.

Sailing at seventeen knots, its top speed, the Liberty overtook and

passed three Soviet ships during its transit of the Strait of Gibraltar.

From there it followed the North African coastline, keeping at least thir-

teen miles from shore. Three days after departing Rota, on June 5, as the

Liberty was passing south of Sicily, Israel began its long-planned strike

against its neighbors and the Arab-Israeli war began.

On June 5, 1967, at 7:45 A.M. Sinai time (1:45 A.M. in Washington, B.C.),

Israel launched virtually its entire air force against Egyptian airfields,

destroying, within eighty minutes, the majority of Egypt's air power. On

the ground, tanks pushed out in three directions across the Sinai toward

the Suez Canal. Fighting was also initiated along the Jordanian and Syr-

ian borders. Simultaneously, Israeli officials put out false reports to the

press saying that Egypt had launched a major attack against them and

that they were defending themselves.

In Washington, June 4 had been a balmy Sunday. President John-

son's national security adviser, Walt Rostow, even stayed home from the

office and turned off his bedroom light at 11:00 P.M. But he turned it

back on at 2:50 A.M. when the phone rang, a little over an hour after Is-

rael launched its attack. "We have an FBIS [Foreign Broadcast Infor-

mation Service] report that the UAR has launched an attack on Israel,"

said a husky male voice from the White House Situation Room. "Go to

your intelligence sources and call me back," barked Rostow. Ten minutes

later, presumably after checking with NSA and other agencies, the aide

called back and confirmed the press story. "Okay, I'm coming in," Ros-

tow said, and then asked for a White House car to pick him up.

As the black Mercury quickly maneuvered through Washington's

empty streets, Rostow ticked off in his mind the order in which he

needed answers. At the top of the list was discovering exactly how the

war had started. A few notches down was deciding when to wake the

president.

The car pulled into the Pennsylvania Avenue gate at 5:25 and Ros-

tow was quickly on the phone with Secretary of State Dean Rusk, who

was still at home. "I assume you've received the Flash," he said. They

agreed that, if the facts were as grim as reported, Johnson should be

awakened in about an hour. Intelligence reports quickly began arriving

indicating that a number of Arab airfields appeared to be inoperative

and the Israelis were pushing hard and fast against the Egyptian air

force.

Sitting at the mahogany conference table in the Situation Room, a

map of Vietnam on the wall, Rostow picked up a phone. "I want to get

through to the President," he said. "I wish him to be awakened." Three

stories above, Lyndon Johnson picked up the phone next to his carved

wood bedstead. "Yes," he said.

"Mr. President, I have the following to report." Rostow got right to

business. "We have information that Israel and the UAR are at war." For

the next seven minutes, the national security adviser gave Johnson the

shorthand version of what the United States then knew.

About the same time in Tel Aviv, Foreign Minister Abba Eban

summoned U.S. Ambassador Walworth Barbour to a meeting in his of-

fice. Building an ever larger curtain of lies around Israel's true activities

and intentions, Eban accused Egypt of starting the war. Barbour quickly

sent a secret Flash message back to Washington. "Early this morning,"

he quoted Eban, "Israelis observed Egyptian units moving in large num-

bers toward Israel and in fact considerable force penetrated Israeli terri-

tory and clashed with Israeli ground forces. Consequently, GOI

[Government of Israel] gave order to attack." Eban told Barbour that his

government intended to protest Egypt's action to the UN Security Coun-

cil. "Israel is [the] victim of Nasser's aggression," he said.

Eban then went on to lie about Israel's goals, which all along had

been to capture as much territory as possible. "GOI has no rpt [repeat]

no intention taking advantage of situation to enlarge its territory. That

hopes peace can be restored within present boundaries." Finally, after

half an hour of deception, Eban brazenly asked the United States to go

up against the USSR on Israel's behalf. Israel, Barbour reported, "asks

our help in restraining any Soviet initiative." The message was received

at the White House at two minutes before six in the morning.

About two hours later, in a windowless office next to the War

Room in the Pentagon, a bell rang five or six times, bringing everyone

to quick attention. A bulky gray Russian Teletype suddenly sprang to

life and keys began pounding out rows of Cyrillic letters at sixty-six

words a minute onto a long white roll of paper. For the first time, an ac-

tual on-line encrypted message was stuttering off the Moscow-to-Wash-

ington hot line. As it was printing, a "presidential translator"—a

military officer expert in Russian—stood over the machine and dictated

a simultaneous rough translation to a Teletype operator. He in turn sent

the message to the State Department, where another translator joined in

working on a translation on which both U.S. experts agreed,

The machine was linked to similar equipment in a room in the

Kremlin, not far from the office of the chairman of the Council of Min-

isters of the USSR. Known formally as the Washington—Moscow Emer-

gency Communications Link (and in Moscow as the Molink), the hot

line was activated at 6:50 P.M. on August 50, 1965, largely as a result of

the Cuban missile crisis.

The message that June morning in 1967 was from Premier Alexei

Kosygin. The Pentagon and State Department translators agreed on the

translation:

Dear Mr. President,

Having received information concerning the military clashes

between Israel and the United Arab Republic, the Soviet

Government is convinced that the duty of all great powers is

to secure the immediate cessation of the military conflict.

The Soviet Government has acted and will act in this

direction. We hope that the Government of the United States

will also act in the same manner and will exert appropriate

influence on the Government of Israel particularly since you

have all opportunities of doing so. This is required in the

highest interest of peace.

Respectfully,

A. Kosygin

Once the presidential translator finished the translation, he rushed

it over to the general in charge of the War Room, who immediately

called Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara several floors above.

McNamara had arrived in his office about an hour earlier. "Premier

Kosygin is on the hot line and asks to speak to the president," the War

Room general barked. "What should I tell him?"

"Why are you calling me?" McNamara asked.

"Because the hot line ends in the Pentagon," the general huffed.

(McNamara later admitted that he had had no idea that the connection

ended a short distance away from him.) "Patch the circuit over to the

White House Situation Room, and I'll call the president," McNamara

ordered.

McNamara, not having been in on the early morning White House

calls, assumed Johnson would still be sleeping, but he put the call

through anyway. A sergeant posted outside the presidential bedroom

picked up the phone. "The president is asleep and doesn't like to be

awakened," he told the Pentagon chief, not realizing that Johnson had

been awake since 4:50 A.M. discussing the crisis. "I know that, but wake

him up," McNamara insisted.

"Mr. President," McNamara said, "the hot line is up and Kosygin

wants to speak to you. What should we say?"

"My God," Johnson replied, apparently perplexed, "what should

we say?" McNamara offered an idea: "I suggest I tell him you will be in

the Situation Room in fifteen minutes. In the meantime, I'll call Dean

and we'll meet you there." Within half an hour, an American-supplied

Teletype was cranking out English letters in the Kremlin. Johnson told

Kosygin that the United States did not intend to intervene in the con-

flict. About a dozen more hot-line messages followed over the next few

weeks.

As the first shots of the war were being fired across the desert wasteland,

NSA had a box seat. A fat Air Force C-150 airborne listening post was

over the eastern Mediterranean flying a figure-eight pattern off Israel

and Egypt. Later the plane landed back at its base, the Greek air force

section of Athens International Airport, with nearly complete coverage

of the first hours of the war.

From the plane, the intercept tapes were rushed to the processing

center, designated USA-512J by NSA. Set up the year before by the U.S.

Air Force Security Service, NSA's air arm, it was to process intercepts—

analyzing the data and attacking lower-level ciphers—produced by Air

Force eavesdropping missions throughout the Mediterranean, North

Africa, and the Middle East. Unfortunately, they were not able to listen

to the tapes of the war immediately because they had no Hebrew lin-

guists. However, an NSA Hebrew linguist support team was at that mo-

ment winging its way to Athens. (To hide their mission and avoid the

implication of spying on Israel, Hebrew linguists were always referred

to as "special Arabic" linguists, even within NSA.)

Soon after the first CRITIC message arrived at NSA, an emergency

notification was sent to the U.S. Navy's listening post at Rota. The base

was the Navy's major launching site for airborne eavesdropping missions

over the Mediterranean area. There the Navy's airborne Sigint unit,

VQ-2, operated large four-engine aircraft that resembled the civilian

passenger plane known as the Constellation, an aircraft with graceful,

curving lines and a large three-section tail. Nicknamed the Willy Victor,

the EC-121M was slow, lumbering, and ideal for eavesdropping—capa-

ble of long, twelve- to eighteen-hour missions, depending on such fac-

tors as weather, fuel, altitude, intercept activity, and crew fatigue.

Within several hours of the tasking message, the EC-121 was air-

borne en route to Athens, from where the missions would be staged. A

few days before, a temporary Navy signals intelligence processing center

had been secretly set up at the Athens airport near the larger U.S. Air

Force Sigint facility. There, intercepts from the missions were to be an-

alyzed and the ciphers attacked.

After landing, the intercept operators were bused to the Hotel

Seville in Iraklion near the Athens airport. The Seville was managed by

a friendly Australian and a Greek named Zina; the crew liked the fact

that the kitchen and bar never closed. But they had barely reached the

lobby of the hotel when they received word they were to get airborne as

soon as possible. "We were in disbelief and mystified," said one member

of the crew. "Surely, our taskers did not expect us to fly into the combat

zone in the dead of the nightl" That was exactly what they expected.

A few hours later, the EC-121 was heading east into the dark night

sky. Normally the flight took about two or three hours. Once over the

eastern Mediterranean, they would maintain a dogleg track about

twenty-five to fifty miles off the Israeli and Egyptian coasts at an alti-

tude of between 12,000 and 18,000 feet. The pattern would take them

from an area northeast of Alexandria, Egypt, east toward Port Said and

the Sinai to the El Arish area, and then dogleg northeast along the Is-

raeli coast to a point west of Beirut, Lebanon. The track would then be

repeated continuously. Another signals intelligence plane, the EA5B,

could fly considerably higher, above 50,000 to 55,000 feet.

On board the EC-121 that night was Navy Chief Petty Officer

Marvin E. Nowicki, who had the unusual qualification of being a He-

brew and Russian linguist. "I vividly recall this night being pitch black,

no stars, no moon, no nothing," he said. "The mission commander con-

sidered the precariousness of our flight. He thought it more prudent to

avoid the usual track. If we headed east off the coast of Egypt toward

Israel, we would look, on radar, to the Israelis like an incoming attack

aircraft from Egypt. Then, assuming the Israelis did not attack us, when

we reversed course, we would then appear on Egyptian radar like Israeli

attack aircraft inbound. It, indeed, was a very dangerous and precarious

situation."

Instead, the mission commander decided to fly between Crete and

Cyprus and then head diagonally toward El Arish in the Sinai along an

established civilian air corridor. Upon reaching a point some twenty-five

miles northeast of El Arish, he would reverse course and begin their

orbit.

"When we arrived on station after midnight, needless to say the

'pucker factor' was high," recalled Nowicki; "the crew was on high,

nervous alert. Nobody slept in the relief bunks on that flight. The night

remained pitch black. What in the devil were we doing out here in the

middle of a war zone, was a question I asked myself several times over

and over during the flight. The adrenaline flowed."

In the small hours of the morning, intercept activity was light.

"The Israelis were home rearming and reloading for the next day's at-

tacks, while the Arabs were bracing themselves for the next onslaught

come daylight and contemplating some kind of counterattack," said

Nowicki. "Eerily, our Comint and Elint positions were quiet." But that

changed as the early-morning sun lit up the battlefields. "Our receivers

came alive with signals mostly from the Israelis as they began their

second day of attacks," Nowicki remembered. Around him, Hebrew

linguists were furiously "gisting"—summarizing—the conversations

between Israeli pilots, while other crew members attempted to combine

that information with signals from airborne radar obtained through

electronic intelligence.

From their lofty perch, they eavesdropped like electronic voyeurs.

The NSA recorders whirred as the Egyptians launched an abortive air

attack on an advancing Israeli armored brigade in the northern Sinai,

only to have their planes shot out of the air by Israeli delta-wing Mirage

aircraft. At one point Nowicki listened to his first midair shootdown as

an Egyptian Sukhoi-7 aircraft was blasted from the sky. "We monitored

as much as we could but soon had to head for Athens because of low

fuel," he said. "We were glad to get the heck out of there."

As they headed back, an Air Force C-150 flying listening post was

heading out to relieve them.

Down below, in the Mediterranean, the Liberty continued its slow jour-

ney toward the war zone as the crew engaged in constant general quar-

ters drills and listened carefully for indications of danger. The Navy

sent out a warning notice to all ships and aircraft in the area to keep at

least 100 nautical miles away from the coasts of Lebanon, Syria, Israel,

and Egypt. But the Liberty was on an espionage mission; unless specif-

ically ordered to change course, Commander McGonagle would con-

tinue steaming full speed ahead. Meanwhile, the Soviet navy had

mobilized their fleet. Some twenty Soviet warships with supporting

vessels and an estimated eight or nine submarines sailed toward the

same flashpoint.

On hearing that war had started, Gene Sheck, an official in NSA's

K Group section, which was responsible for managing the various mo-

bile collection platforms, became increasingly worried about the Lib-

erty. Responsibility for the safety of the ship, however, had been taken

out of NSA's hands by the JCS and given to the Joint Reconnaissance

Center. Nevertheless, Sheck took it upon himself to remind NSA's rep-

resentative at the JRC, John Connell, that during the Cuban missile cri-

sis five years earlier, the Oxford had been pulled back from the Havana

area. Then he asked if any consideration was being given to doing the

same for the Liberty. Connell spoke to the ship movement officer at the

JRC but they refused to take any action.

Although analysts in K Group knew of the Liberty's plight, those

in G Group did not. Thus it was not until the morning of June 7 that an

analyst rushed into Frank Raven's office and asked incredulously, "For

God's sake, do you know where the Liberty is?" Raven, believing she was

sitting off the east end of Crete as originally planned, had barely begun

to answer when the analyst blurted out, "They've got her heading

straight for the beach!" By then the Liberty was only about ten hours

from her scheduled patrol area, a dozen miles off Egypt's Sinai Desert.

"At this point," recalled Raven, "I ordered a major complaint

[protest] to get the Liberty the hell out of there! As far as we [NSA] were

concerned, there was nothing to be gained by having her in there that

close, nothing she could do in there that she couldn't do where we

wanted her. . . . She could do everything that the national require-

ment called for [from the coast of Crete]. Somebody wanted to listen to

some close tactical program or some communications or something

which nobody in the world gave a damn about—local military base,

local commander. We were listening for the higher echelons. . . . Hell,

you don't want to hear them move the tugboats around and such, you

want to know what the commanding generals are saying."

The JRC began reevaluating the Liberty's safety as the warnings

mounted. The Egyptians began sending out ominous protests complain-

ing that U.S. personnel were secretly communicating with Israel and

were possibly providing military assistance. Egypt also charged that U.S.

aircraft had participated in the Israeli air strikes. The charges greatly

worried American officials, who feared that the announcements might

provoke a Soviet reaction. Then the Chief of Naval Operations ques-

tioned the wisdom of the Liberty assignment.

As a result of these new concerns, the JRC sent out a message in-

dicating that the Liberty's operational area off the Sinai was not set in

stone but was "for guidance only." Also, it pulled the ship back from 12Va

to 20 nautical miles from the coast. By now it was about 6:50 P.M. in

Washington, half past midnight on the morning of June 8 in Egypt. The

Liberty had already entered the outskirts of its operational area and the

message never reached her because of an error by the U.S. Army Com-

munications Center at the Pentagon.

About an hour later, with fears mounting, the JRC again changed

the order, now requiring that Liberty approach no closer than 100 miles

to the coasts of Egypt and Israel. Knowing the ship was getting danger-

ously close, Major Breedlove in the JRC skipped the normal slow mes-

sage system and called Navy officials in Europe over a secure telephone

to tell them of the change. He said a confirming message would follow.

Within ten minutes the Navy lieutenant in Europe had a warning mes-

sage ready.

But rather than issue the warning, a Navy captain in Europe in-

sisted on waiting until he received the confirmation message. That and

a series of Keystone Kops foul-ups by both the Navy and Army—which

again misrouted the message, this time to Hawaii—delayed sending the

critical message for an incredible sixteen and a half hours. By then it

was far too late. More than twenty years had gone by since the foul-up

of warning messages at the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor, yet it

was as if no lesson had ever been learned.

At 5:14 A.M. on Thursday, June 8, the first rays of sun spilled softly over

the Sinai's blond waves of sand. A little more than a dozen miles north,

in the choppy eastern Mediterranean, the Liberty continued eastward

like a lost innocent, 600 miles from the nearest help and oblivious to at

least five warning messages it never received. The "Plan of the Day"

distributed throughout the ship that morning gave no hint of what was

in store. "Uniform of the Day" for officers was "tropical wash khaki"

and, for enlisted men, "clean dungarees." The soda fountain, crewmem-

bers were informed, would be open from 6:00 P.M. until 7:50 P.M.

Just after sunup, Duty Officer John Scott noticed a flying boxcar

making several circles near the ship and then departing in the direction

of Tel Aviv. Down in the NSA spaces, Chief Melvin Smith apparently

also picked up signals from the plane, later identified as Israeli. Shortly

after the plane departed, he called up Scott and asked if he had had a

close air contact recently. Scott told him he had, and Smith asked which

direction it had gone in. "Tel Aviv," said Scott. "Fine, that's all I want to

know," replied Smith. Scott glanced up at the American flag, ruffling in

a twelve-knot breeze, to check the wind direction, and then scanned the

vast desert a little more than a dozen miles away. "Fabulous morning,"

he said without dropping the stubby binoculars from. his eyes.

But the calmness was like quicksand—deceptive, inviting, and

friendly, until too late. As the Liberty passed the desert town of El Arish,

it was closely watched. About half a mile away and 4,000 feet above was

an Israeli reconnaissance aircraft. At 6:05 A.M. the naval observer on the

plane reported back to Israeli naval headquarters, "What we could see

was the letters written on that ship," he said. "And we gave these letters

to the ground control." The letters were "GTR-5," the Liberty's identi-

fication. "GTR" stood for "General Technical Research"—a cover des-

ignation for NSA's fleet of spy ships.

Having passed El Arish, the Liberty continued on toward the Gaza

Strip. Then, about 8:50 A.M., it made a strange, nearly 180-degree turn

back in the direction of El Arish and slowed down to just five knots. The

reason for this maneuver was that the ship had at last reached Point

Alpha, the point on the map where it was to begin its back-and-forth

dogleg patrol of the Sinai coast.

For some time, Commander McGonagle had been worried about

the ship's proximity to the shore and about the potential for danger. He

called to his cabin Lieutenant Commander David E. Lewis, head of the

NSA operation on the ship. "How would it affect our mission if we

stayed farther out at sea?" McGonagle asked. "It would hurt us, Cap-

tain," Lewis replied. "We want to work in the UFH [ultra-high-fre-

quency] range. That's mostly line-of-sight stuff. If we're over the

horizon we might as well be back in Abidjan. It would degrade our mis-

sion by about eighty percent." After thinking for a few minutes, McGon-

agle made his decision, "Okay," he said. "We'll go all the way in."

The reconnaissance was repeated at approximately thirty-minute

intervals throughout the morning. At one point, a boxy Israeli air force

Noratlas NORD 2501 circled the ship around the starboard side, pro-

ceeded forward of the ship, and headed back toward the Sinai. "It had

a big Star of David on it and it was flying just a little bit above our

mast on the ship," recalled crewmember Larry Weaver. "We really

thought his wing was actually going to clip one of our masts. . . .

And I was actually able to wave to the co-pilot, a fellow on the right-

hand side of the plane. He waved back, and actually smiled at me. I

could see him that well. I didn't think anything of that because they

were our allies. There's no question about it. They had seen the ship's

markings and the American flag. They could damn near see my rank.

The under way flag was definitely flying. Especially when you're that

close to a war zone." '

By 9:50 A.M. the minaret at El Arish could be seen with the naked

eye, like a solitary mast in a sea of sand. Visibility in the crystal clear air

was twenty-five miles or better. Through a pair of binoculars, individual

buildings were clearly visible a brief thirteen miles away. Commander

McGonagle thought the tower "quite conspicuous" and used it as a nav-

igational aid to determine the ship's position throughout the morning

and afternoon. The minaret was also identifiable by radar.

Although no one on the ship knew it at the time, the Liberty had

suddenly trespassed into a private horror. At that very moment, near the

minaret at El Arish, Israeli forces were engaged in a criminal slaughter.

From the first minutes of its surprise attack, the Israeli air force

had owned the skies over the Middle East. Within the first few hours, Is-

raeli jets pounded twenty-five Arab air bases ranging from Damascus in

Syria to an Egyptian field, loaded with bombers, far up the Nile at

Luxor. Then, using machine guns, mortar fire, tanks, and air power, the

Israeli war machine overtook the Jordanian section of Jerusalem as well

as the west bank of the Jordan River, and torpedo boats captured the key

Red Sea cape of Sharm al-Sheikh.

In the Sinai, Israeli tanks and armored personnel carriers pushed

toward the Suez Canal along all three of the roads that crossed the

desert, turning the burning sands into a massive killing field. One Israeli

general estimated that Egyptian casualties there ranged from 7,000 to

10,000 killed, compared with 275 of his own troops. Few were spared as

the Israelis pushed forward.

A convoy of Indian peacekeeper soldiers, flying the blue United

Nations flag from their jeeps and trucks, were on their way to Gaza

when they met an Israeli tank column on the road. As the Israelis ap-

proached, the UN observers pulled aside and stopped to get out of the

way. One of the tanks rotated its turret and opened fire from a few feet

away. The Israeli tank then rammed its gun through the windshield of

an Indian jeep and decapitated the two men inside. When other Indians

went to aid their comrades, they were mowed down by machine-gun

fire. Another Israeli tank thrust its gun into a UN truck, lifted it, and

smashed it to the ground, killing or wounding all the occupants. In Gaza,

Israeli tanks blasted six rounds into UN headquarters, which was flying

the UN flag. Fourteen UN members were killed in these incidents. One

Indian officer called it deliberate, cold-blooded killing of unarmed UN

soldiers. It would be a sign of things to come.

By June 8, three days after Israel launched the war, Egyptian pris-

oners in the Sinai had become nuisances. There was no place to house

them, not enough Israelis to watch them, and few vehicles to transport

them to prison camps. But there was another way to deal with them.

As the Liberty sat within eyeshot of El Arish, eavesdropping on

surrounding communications, Israeli soldiers turned the town into a

slaughterhouse, systematically butchering their prisoners. In the shadow

of the El Arish mosque, they lined up about sixty unarmed Egyptian

prisoners, hands tied behind their backs, and then opened fire with ma-

chine guns until the pale desert sand turned red. Then they forced other

prisoners to bury the victims in mass graves. "I saw a line of prisoners,

civilians and military," said Abdelsalam Moussa, one of those who dug

the graves, "and they opened fire at them all at once. When they were

dead, they told us to bury them." Nearby, another group of Israelis

gunned down thirty more prisoners and then ordered some Bedouins to

cover them with sand.

In still another incident at El Arish, the Israeli journalist Gabi

Bron saw about 150 Egyptian POWs sitting on the ground, crowded to-

gether with their hands held at the backs of their necks. "The Egyptian

prisoners of war were ordered to dig pits and then army police shot

them to death," Bron said. "I witnessed the executions with my own

eyes on the morning of June eighth, in the airport area of El Arish."

The Israeli military historian Aryeh Yitzhaki, who worked in the

army's history department after the war, said he and other officers col-

lected testimony from dozens of soldiers who admitted killing POWs.

According to Yitzhaki, Israeli troops killed, in cold blood, as many as

1,000 Egyptian prisoners in the Sinai, including some 400 in the sand

dunes of El Arish.

Ironically, Ariel Sharon, who was capturing territory south of El

Arish at the time of the slaughter, had been close to massacres during

other conflicts. One of his men during the Suez crisis in 1956, Arye Biro,

now a retired brigadier general, recently admitted the unprovoked

killing of forty-nine prisoners of war in the Sinai in 1956. "I had my

Karl Gustav [weapon] I had taken from the Egyptian. My officer had an

Uzi. The Egyptian prisoners were sitting there with their faces turned

to us. We turned to them with our loaded guns and shot them. Magazine

after magazine. They didn't get a chance to react." At another point,

Biro said, he found Egyptian soldiers prostrate with thirst. He said that

after taunting them by pouring water from his canteen into the sand, he

killed them. "If I were to be put on trial for what I did," he said, "then

it would be necessary to put on trial at least one-half the Israeli army,

which, in similar circumstances, did what I did." Sharon, who says he

learned of the 1956 prisoner shootings only after they happened, refused

to say whether he took any disciplinary action against those involved, or

even objected to the killings.

Later in his career, in 1982, Sharon would be held "indirectly re-

sponsible" for the slaughter of about 900 men, women, and children by

Lebanese Christian militia at the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps fol-

lowing Israel's invasion of Lebanon. Despite his grisly past, or maybe

because of it, in October 1998 he was appointed minister of foreign af-

fairs in the cabinet of right-wing prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

Sharon later took over the conservative Likud Party. On September 28,

2000, he set off the bloodiest upheaval between Israeli forces and Pales-

tinians in a generation, which resulted in a collapse of the seven-year

peace process. The deadly battles, which killed over 200 Palestinians and

several Israeli soldiers, broke out following a provocative visit by Sharon

to the compound known as Haram as-Sharif (Noble Sanctuary) to Mus-

lims and Temple Mount to Jews. Addressing the question of Israeli war

crimes, Sharon said in 1995, "Israel doesn't need this, and no one can

preach to us about it—no one."

Of the 1967 Sinai slaughter, Aryeh Yitzhaki said, "The whole

army leadership, including [then] Defense Minister Moshe Dayan and

Chief of Staff [and later Prime Minister Yitzhak] Rabin and the gener-

als knew about these things. No one bothered to denounce them."

Yitzhaki said not only were the massacres known, but senior Israeli of-

ficials tried their best to cover them up by not releasing a report he had

prepared on the murders in 1968.

The extensive war crimes were just one of the deep secrets Israel

had sought to conceal since the start of the conflict. From the very be-

ginning, an essential element in the Israeli battle plan seemed to have

been to hide much of the war behind a carefully constructed curtain of

lies. Lies about the Egyptian threat, lies about who started the war, lies

to the American president, lies to the UN Security Council, lies to the

press, lies to the public. Thus, as the American naval historian Dr.

Richard K. Smith noted in an article on the Liberty for United States

Naval Institute Proceedings, "any instrument which sought to penetrate

this smoke screen so carefully thrown around the normal 'fog of war'

would have to be frustrated."

Into this sea of lies, deception, and slaughter sailed the USS Lib-

erty, an enormous American spy factory loaded with $10.2 million

worth of the latest eavesdropping gear. At 10:59 A.M., the minaret at El

Arish was logged at seventeen miles away, at bearing 189 degrees. Sail-

ing at five knots, the Liberty was practically treading water.

By 10:55 A.M., senior Israeli officials knew for certain that they had

an American electronic spy in their midst. Not only was the ship clearly

visible to the forces at El Arish, it had been positively identified by Is-

raeli naval headquarters.

The Israeli naval observer on the airborne reconnaissance mission

that had earlier observed the Liberty passed on the information to Com-

mander Pinchas Pinchasy, the naval liaison officer at Israeli air force

headquarters. "I reported this detection to Naval Headquarters," said

Pinchasy, "and I imagine that Naval Headquarters received this report

from the other channel, from the Air Force ground control as well." Pin-

chasy had pulled out a copy of the reference book Jane's Fighting Ships

and looked up the "GTR.-5" designation. He then sent a report to the

acting chief of naval operations at Israeli navy headquarters in Haifa.

The report said that the ship cruising slowly off El Arish was "an elec-

tromagnetic audio-surveillance ship of the U.S. Navy, named Liberty,

whose marking was GTR.-5."

Not only did the ship have "GTR-5" painted broadly on both sides

of its bow and stern, it also had its name painted in large, bold, black let-

ters: "U.S.S. LIBERTY."

Although no one on the Liberty knew it, they were about to have

some company.

"We were 'wheels in the well' from Athens about mid-morning," said

Marvin Nowicki, who was aboard the EC-121 headed back to the war

zone. In the rear NSA spaces, the crew strapped on their seat belts. It was

an everyday routine. The VQ-2 squadron would fly, on average, six to

twelve missions per month against Israel and the Arab countries of the

Middle East. Exceptions took place when higher-priority Soviet targets

came up, for example when the Soviet fleet conducted exercises in the

Mediterranean or Norwegian Sea. Nowicki himself accumulated over

2,000 hours in such spy planes over his career.

Back at Athens Airport, the 512J processing center had been beefed

up to help analyze the increasing flow of intercepts. Three NSA civilian

Hebrew linguists had arrived and were attacking the backlog of record-

ing tapes. The pile had grown especially large because the Air Force had

no Hebrew linguists for their C-150 Sigint aircraft. "As it turns out," said

Nowicki, "they were blindly copying any voice signal that sounded He-

brew. They were like vacuum, cleaners, sucking every signal onto their

recorders, with the intercept operators not having a clue as to what the

activity represented."

In charge of the half-dozen Elint specialists aboard the EC-121,

searching for radar signals and analyzing their cryptic sounds, was the

evaluator, who would attempt to make sense of all the data. Elsewhere,

several intercept operators were assigned to monitor VHF and UHF

radio-telephone signals. In addition to Chief Nowicki, who could trans-

late both Hebrew and Russian, there were two other Hebrew and two

Arabic linguists on board.

Soon after wheels-up from. Athens, a security curtain was pulled

around the "spook spaces" to hide the activity from members of the

flight crew who did not have a need to know. In front of the voice-in-

tercept operators were twin UHF/VHF receivers, essential because the

Israelis mostly used UHF transceivers, while the Arabs used Soviet VHF

equipment. To record all the traffic, they had a four-track voice recorder

with time dubs and frequency notations. Chief Nowicki, the supervisor,

had an additional piece of equipment: a spectrum analyzer to view the

radio activity in the form of "spikes" between 100 to 150 megahertz and

200 to 500 megahertz. It was very useful in locating new signals.

About noon, as they came closer to their orbit area, the activity

began getting hectic. Fingers twisted large black dials, sometimes

quickly and sometimes barely at all. "When we arrived within intercept

range of the battles already in progress," Nowicki recalled, "it was ap-

parent that the Israelis were pounding the Syrians on the Golan

Heights. Soon all our recorders were going full blast, with each position

intercepting signals on both receivers."

In addition to recording the voices of the Israeli and Egyptian

troops and pilots, the linguists were frantically writing down gists of

voice activity on logs and shouting to the evaluator what they were

recording. The evaluator in turn would then direct his Elint people to

search for corresponding radar activity. At other times, the Elint opera-

tors would intercept a radar signal from a target and tip off the linguists

to start searching for correlating voice activity. A key piece of equipment

was known as Big Look. It enabled the Elint operators to intercept, em-

ulate, and identify the radar signals, and to reverse-locate them—to

trace them back to their source.

Sixty miles north of Tel Aviv, atop Mount Carmel, Israel's naval com-

mand post occupied a drab former British Royal Air Force base built in

the 1920s. Known as Stella Marts, it contained a high-ceilinged war

room with a large map of Israel and its coastal areas on a raised plat-

form. Standing above it, senior naval officials could see the location of

ships in the area, updated as air reconnaissance passed on the changing

positions of various ships. Since dawn that morning, the Liberty had

been under constant observation. "Between five in the morning and one

in the afternoon," said one Liberty deck officer, "I think there were thir-

teen times that we were circled."

About noon at Stella Marts, as the Liberty was again in sight of El

Arish and while the massacres were taking place, a report was received

from an army commander there that a ship was shelling the Israelis

from the sea. But that was impossible. The only ship in the vicinity of

El Arish was the Liberty, and she was eavesdropping, not shooting. As

any observer would immediately have recognized, the four small defen-

sive 50mm machine guns were incapable of reaching anywhere near the

shore, thirteen miles away, let alone the buildings of El Arish. In fact,

the maximum effective range of such guns was just 2,200 yards, a little

over a mile. And the ship itself, a tired old World War II cargo vessel

crawling with antennas, was unthreatening to anyone—unless it was

their secrets, not their lives, they wanted to protect.

By then the Israeli navy and air force had conducted more than six

hours of close surveillance of the Liberty off the Sinai, even taken pic-

tures, and must have positively identified it as an American electronic

spy ship. They knew the Liberty was the only military ship in the area.

Nevertheless, the order was given to kill it. Thus, at 12:05 P.M. three

motor torpedo boats from Ashdod departed for the Liberty, about fifty

miles away. Israeli air force fighters, loaded with 50mm cannon ammu-

nition, rockets, and even napalm, then followed. They were all to return

virtually empty.

At 1:41 P.M., about an hour and a half after leaving A-shdod, the tor-

pedo boats spotted the Liberty off El Arish and called for an immediate

strike by the air force fighters.

On the bridge of the Liberty, Commander McGonagle looked at the

hooded green radar screen and fixed the ship's position as being 25V2

nautical miles from the minaret at El Arish, which was to the southeast.

The officer of the deck, Lieutenant (junior grade) Lloyd Painter, also

looked at the radar and saw that they were \7Vt miles from. land. It was

shortly before two o'clock in the afternoon.

McGonagle was known as a steamer, a sailor who wants to con-

stantly feel the motion of the sea beneath the hull of the ship, to steam

to the next port as soon as possible after arriving at the last. "He longed

for the sea," said one of his officers, "and was noticeably restless in port.

He simply would not tolerate being delayed by machinery that was not

vital to the operation of the ship." He was born in Wichita, Kansas, on

November 19, 1925, and his voice still had a twang. Among the first

to join the post—World War II Navy, he saw combat while on a

minesweeper during the Korean War, winning the Korean Service

Medal with six battle stars. Eventually commanding several small ser-

vice ships, he had taken over as captain of the Liberty about a year ear-

lier, in April 1966.

A Chief of Naval Operations once called the Liberty "the ugliest

ship in the Navy," largely because in place of powerful guns it had

strange antennas protruding from every location. There were thin long-

wire VLF antennas, conical electronic-countermeasure antennas, spira-

cle antennas, a microwave antenna on the bow, and whip antennas that

extended thirty-five feet. Most unusual was the sixteen-foot dish-shaped

moon-bounce antenna that rested high on the stern.

Despite the danger, the men on the ship were carrying on as nor-

mally as possible. Larry Weaver, a boatswain's mate, was waiting outside

the doctor's office to have an earache looked at. Muscular at 184 pounds,

he exercised regularly in the ship's weight room. Planning to leave the

Navy shortly, he had already applied for a job at Florida's Cypress Gar-

dens as a water skier. With the ability to ski barefoot for nine miles, he

thought he would have a good chance.

As for Bryce Lock-wood, the Marine senior Russian linguist who

had been awakened in the middle of a layover in Rota, Spain, and vir-

tually shanghaied, his wife and daughter had no idea where he was.

Having boarded the ship on such short notice, Lockwood had gone to the

small ship's store to buy some T-shirts and shorts. While waiting to go

on watch, he was sitting on his bunk stamping his name in his new un-

derwear.

On the stern, Stan White was struggling with the troublesome

moon-bounce antenna. A senior chief petty officer, he was responsible

for the complicated repair of the intercept and cipher gear on board.

The giant dish was used to communicate quickly, directly, and securely

with NSA back at Fort Meade, and for this purpose both locations had to

be able to see the moon at the same time. But throughout the whole voy-

age, even back in Norfolk, the system was plagued with leaking hy-

draulic fluid. Now another critical part, the klystron, had burned out and

White was attempting to replace it.

Below deck in the Research Operations Department, as the NSA

spaces were known, Elint operators were huddled over round green

scopes, watching and listening for any unusual signals. Charles L. Row-

ley, a first-class petty officer and a specialist in technical intelligence col-

lection, was in charge of one of the Elint sections. "I was told to be on

the lookout for a different type of signal," he said. "I reported a signal I

thought was from a submarine. ... I analyzed it as far as the length of

the signal, the mark and space on the bods, and I could not break it, I

didn't know what it was, I had no idea what it was . . . and sent it in to

NSA." But NSA had an unusual reaction: "I got my butt chewed out.

They tried to convince me that it was a British double-current cable code

and I know damn good and well that it wasn't." In fact, the blackness

deep beneath the waves of the eastern Mediterranean was beginning to

become quite crowded.

One deck down, just below the waterline, were the Morse code as

well as Russian and Arabic voice-intercept operators, their "cans" tight

against their ears. Lined up along the bulkheads, they pounded away on

typewriters and flipped tape recorders on and off as they eavesdropped on

the sounds of war. Among their key missions was to determine whether

the Egyptian air force's Soviet-made bombers, such as the TU-95 aircraft

thought to be based in Alexandria, were being flown and controlled by

Russian pilots and ground controllers. Obtaining the earliest intelli-

gence that the Russians were taking part in the fighting was one of the

principal reasons for sending the Liberty so far into the war zone.

In another office, communications personnel worked on the ship's

special, highly encrypted communications equipment.

Nearby in the Coordination—"Co-ord"—spaces, technicians were

shredding all outdated documents to protect them from possible capture.

Others were engaged in "processing and reporting," or P&R. "Process-

ing and reporting involves figuring out who is talking," said Bryce Lock-

wood, one of the P&R supervisors, "where they're coming from, the

other stations on that network, making some kind of sense out of it, for-

warding it to the consumers, which primarily was the NSA, the CIA,

JCS."

But as the real war raged on the shore, a mock war raged in the Co-

ord spaces. One of the Arabic-language P&R specialists had developed a

fondness for Egypt and had made a small Egyptian flag that he put on

his desk. "The guys would walk by and they would take a cigarette

lighter," recalled Lockwood, "and say, 'Hey, what's happening to the

UAR [United Arab Republic, now Egypt] over there?' And they would

light off his UAR flag and he would reach over and say, 'Stop that,' and

put the fire out, and it was getting all scorched."

Then, according to Lockwood, some of the pro-Israel contingent

got their revenge. They "had gotten Teletype paper and scotch-taped it

together and with blue felt marking pens had made a gigantic Star of

David flag. This thing was about six feet by about twelve feet—huge.

And stuck that up on the starboard bulkhead."

"You'd better call the forward gun mounts," Commander McGonagle

yelled excitedly to Lieutenant Painter. "I think they're going to attack!"

The captain was standing on the starboard wing, looking at a number of

unidentified jet aircraft rapidly approaching in an attack pattern.

Larry Weaver was still sitting outside the doctor's office when he

first heard the sound. A few minutes before, an announcement had come

over the speaker saying that the engine on the motor whaleboat was

about to be tested. "All of a sudden I heard this rat-a-tat-tat real hard

and the first thing I thought was, 'Holy shit, the prop came off that boat

and went right up the bulkhead,' that's exactly what it sounded like.

And the very next instant we heard the gong and we went to general

quarters."

Stan White thought it sounded like someone throwing rocks at the

ship. "And then it happened again," he recalled, "and then general quar-

ters sounded, and by the captain's voice we knew it was not a drill.

Shortly after that the wave-guides to the dish [antenna] were shot to

pieces and sparks and chunks fell on me."

"I immediately knew what it was," said Bryce Lockwood, the Ma-

rine, "and I just dropped everything and ran to my GQ station which

was down below in the Co-ord station."

Without warning the Israeli jets struck—swept-wing Dassault Mi-

rage IIICs. Lieutenant Painter observed that the aircraft had "absolutely

no markings," so that their identity was unclear. He then attempted to

contact the men manning the gun mounts, but it was too late. "I was try-

ing to contact these two kids," he recalled, "and I saw them both; well,

I didn't exactly see them as such. They were blown apart, but I saw the

whole area go up in smoke and scattered metal. And, at about the same

time, the aircraft strafed the bridge area itself. The quartermaster, Petty

Officer Third Class Pollard, was standing right next to me, and he was

hit."

With the sun at their backs in true attack mode, the Mirages raked

the ship from bow to stern with hot, armor-piercing lead. Back and forth

they came, cannons and machine guns blazing. A bomb exploded near

the whaleboat aft of the bridge, and those in the pilothouse and the

bridge were thrown from their feet. Commander McGonagle grabbed

for the engine order annunciator and rang up all ahead flank.

"Oil is spilling out into the water," one of the Israeli Mirage pilots

reported to b

http://www.ussliberty.org/

BODY OF SECRETS

JAMES BAMFORD

Anatomy of the Ultra-Secret National Security Agency from the Cold War through a New Century

Doubleday New york London Toronto Sydney Auckland

________________________________________________________________________________________________

PUBLISHED BY DOUBLEDAY

A division of Random House, Inc.

1540 Broadway, New York, New York 10056

DOUBLEDAY and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are

trademarks of Doubleday, a division of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bamford, James,

Body of secrets: anatomy of the ultra-secret National Security Agency:

from the Cold War through the dawn of a new century /

James Bamford.—1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. United States. National Security Agency—History. 2. Electronic

intelligence—United States—History. 3. Cryptography—United

States—History. I. Title.

UB256.U6 B56 2001

527.1273—dc21

00-058920

ISBN 0-585-49907-8

Book design by Maria Carella

Copyright © 2001 by James Bamford

All Rights Reserved

Printed in the United States of America

May 2001

First Edition

15579 10 8642

_______________________________________________________________________________________

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My most sincere thanks to the many people who helped bring Body of

Secrets to life. Lieutenant General Michael V. Hayden, NSA's director,

had the courage to open the agency's door a crack. Major General John

E. Morrison (Retired), the dean of the U.S. intelligence community, was

always gracious and accommodating in pointing me in the right direc-

tions. Deborah Price suffered through my endless Freedom of Informa-

tion Act requests with professionalism and good humor. Judith Emmel

and Colleen Garrett helped guide me through the labyrinths of Crypto

City. Jack Ingram, Dr. David Hatch, Jennifer Wilcox, and Rowena

Clough of NSA's National Cryptologic Museum provided endless help in

researching the agency's past.

Critical was the help of those who fought on the front lines of the

cryptologic wars, including George A. Cassidy, Richard G. Schmucker,

Marvin Nowicki, John Arnold, Harry 0. Rakfeldt, David Parks, John

Mastro, Wayne Madsen, Aubrey Rrown, John R. DeChene, Bryce Lock-

wood, Richard McCarthy, Don McClarren, Stuart Russell, Richard E.

Kerr, Jr., James Miller, and many others. My grateful appreciation to all

those named and unnamed.

Thanks also to David J. Haight and Dwight E. Strandberg of the

Dwight D. Elsenhower Presidential Library and to Thomas E. Samoluk

of the U.S. Assassinations Records Review Board.

Finally I would like to thank those who helped give birth to Body

of Secrets, including Kris Dahl, my agent at International Creative

Management; Shawn Coyne, my editor at Doubleday; and Bill Thomas,

Bette Alexander, Jolanta Benal, Lauren Field, Chris Min, Timothy Hsu,

and Sean Desmond.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Chapter Seven - BLOOD

For four years NSA's "African Queen" lumbered inconspicuously up and

down the wild and troubled East African coast with the speed of an old

sea turtle. By the spring of 1967, the tropical waters had so encrusted her

bottom with sea life that her top speed was down to between three and

five knots. With Che Guevara long since gone back to Cuba, NSA's G

Group, responsible for the non-Communist portion of the planet, de-

cided to finally relieve the Valdez and send her back to Norfolk, where

she could be beached and scraped.

It was also decided to take maximum advantage of the situation by

bringing the ship home through the Suez Canal, mapping and charting

the radio spectrum as she crawled slowly past the Middle East and the

eastern Mediterranean. "Now, frankly," recalled Frank Raven, former

chief of G Group, "we didn't think at that point that it was highly de-

sirable to have a ship right in the Middle East; it would be too explosive

a situation. But the Valdez, obviously coming home with a foul bottom

and pulling no bones about it and being a civilian ship, could get away

with it." It took the ship about six weeks to come up through the canal

and limp down the North African coast past Israel, Egypt, and Libya.

About that same time, the Valdez's African partner, the USS Lib-

erty, was arriving off West Africa, following a stormy Atlantic crossing,

for the start of its fifth patrol. Navy Commander William L. McGona-

gle, its newest captain, ordered the speed reduced to four knots, the low-

est speed at which the Liberty could easily answer its rudder, and the

ship began its slow crawl south. On May 22, the Liberty pulled into

Abidjan, capital of the Ivory Coast, for a four-day port call.

Half the earth away, behind cipher-locked doors at NSA, the talk

was not of possible African coups but of potential Middle East wars. The

indications had been growing for weeks, like swells before a storm. On

the Israeli-Syrian border, what started out as potshots at tractors had

quickly escalated to cannon fire between tanks. On May 17, Egypt (then

known as the United Arab Republic [UAR]) evicted UN peacekeepers

and then moved troops to its Sinai border with Israel. A few days later,

Israeli tanks were reported on the Sinai frontier, and the following day

Egypt ordered mobilization of 100,000 armed reserves. On May 25,

Gamal Abdel Nasser blockaded the Strait of Tiran, thereby closing the

Gulf of Aqaba to Israeli shipping and prohibiting unescorted tankers

under any flag from reaching the Israeli port of Elat. The Israelis de-

clared the action "an act of aggression against Israel" and began a full-

scale mobilization.

As NSA's ears strained for information, Israeli officials began ar-

riving in Washington. Nasser, they said, was about to launch a lopsided

war against them and they needed American support. It was a lie. In

fact, as Menachem Begin admitted years later, it was Israel that was

planning a first strike attack on Egypt. "We . . . had a choice," Begin

said in 1982, when he was Israel's prime minister. "The Egyptian army

concentrations in the Sinai approaches do not prove that Nasser was re-

ally about to attack us. We must be honest with ourselves. We decided to

attack him."

Had Israel brought the United States into a first-strike war against

Egypt and the Arab world, the results might have been calamitous. The

USSR would almost certainly have gone to the defense of its Arab

friends, leading to a direct battlefield confrontation between U.S. and

Soviet forces. Such a dangerous prospect could have touched off a nu-

clear war.

With the growing possibility of U.S. involvement in a Middle East

war, the Joint Chiefs of Staff needed rapid intelligence on the ground

situation in Egypt. Above all, they wanted to know how many Soviet

troops, if any, were currently in Egypt and what kinds of weapons they

had. Also, if U.S. fighter planes were to enter the conflict, it was essen-

tial to pinpoint the locations of surface-to-air missile batteries. If troops

went in, it would be vital to know the locations and strength of oppos-

ing forces.

Under the gun to provide answers, officials at NSA considered

their options. Land-based stations, like the one in Cyprus, were too far

away to collect the narrow line-of-sight signals used by air defense radar,

fire control radar, microwave communications, and other targets.

Airborne Sigint platforms—Air Force C-150s and Navy EC-121s—

could collect some of this. But after allowing for time to and from the

"orbit areas," the aircrews would only have about five hours on sta-

tion—too short a time for the sustained collection that was required.

Adding aircraft was also an option but finding extra signals intelligence

planes would be very difficult. Also, downtime and maintenance on

those aircraft was greater than for any other kind of platform.

Finally there were the ships, which was the best option. Because

they could sail relatively close, they could pick up the most important

signals. Also, unlike the aircraft, they could remain on station for weeks

at a time, eavesdropping, locating transmitters, and analyzing the intel-

ligence. At the time, the USS Oxford, and Jamestown were in Southeast

Asia; the USS Georgetown and Belmont were eavesdropping off South

America; and the USNS Muller was monitoring signals off Cuba. That

left the USNS Faldez and the USS Liberty. The Valdez. had just com-

pleted a long mission and was near Gibraltar on its way back to the

United States. On the other hand, the Liberty, which was larger and

faster, had just begun a new mission and was relatively close, in port in

Abidjan.

Several months before, seeing the swells forming, NSA's G Group

had drawn up a contingency plan. It would position the Liberty in the

area of "LOLO" (longitude 0, latitude 0) in Africa's Gulf of Guinea, con-

centrating on targets in that area, but actually positioning her far

enough north that she could make a dash for the Middle East should the

need arise. Despite the advantages, not everyone agreed on the plan.

Frank Raven, the G Group chief, argued that it was too risky. "The ship

will be defenseless out there," he insisted. "If war breaks out, she'll be

alone and vulnerable. Either side might start shooting at her. ... I say

the ship should be left where it is." But he was overruled.

On May 25, having decided to send the Liberty to the Middle East,

G Group officials notified John Connell, NSA's man at the Joint Recon-