From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

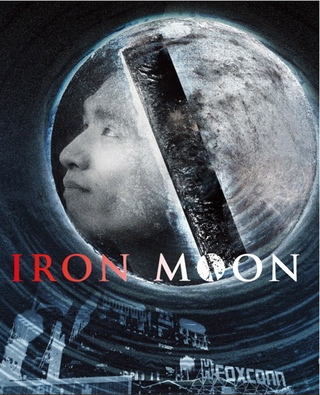

SF Screening of Iron Moon: The Poetry of Chinese Migrant Workers & poet Chen Nianxi (陳年喜

Date:

Saturday, November 19, 2016

Time:

7:00 PM

-

9:30 PM

Event Type:

Screening

Organizer/Author:

LaborFest

Location Details:

ILWU Local 34

801 2nd St.

San Francisco, California

801 2nd St.

San Francisco, California

11/19 SF Special Premier Screening of

Iron Moon: The Poetry of Chinese Migrant Workers

A documentary film directed by Xiaoyu Qin and Feiyue Wu followed by a discussion with the directors and reading by poet Chen Nianxi (陳年喜), who is a demolitions worker and poet for 16 years

Saturday November 19, 2016 7:00 PM

ILWU Local 34

801 2nd St. San Francisco

Sponsored by

LaborFest

http://www.laborfest.net

(415)642-8066

laborfest [at] laborfest.net

For reservations contact LaborFest

About the documentary film:

An assembly line worker in an Apple factory who commits suicide at the young age of 24, leaving behind 200 poems of despair—“I swallowed an iron moon…..”; a guileless lathe operator who is rebuffed at every turn, living in the world of his poetry; a female clothing factory worker who lives in poverty but writes poetry rich in dignity and love; a coalminer who works deep in the earth year round, trying to contact and make peace with the spirits of his dead coworkers through his poetry; and a goldmine demolitions worker who blasts rocks several kilometers into mountainsides to support his family, while writing poetry to carry the weight of his fury and affections—“My body carries three tons of dynamite….” They could be any of the 350 million workers in China, and yet these five are also poets. Using poetry as a tool to chip away at the ice of silence, they express the hidden life stories and experiences of people living at the bottom of the society. This is one story behind the sudden rise of China, and a mournful song of global capitalism.

Iron Moon: The Poetry of Chinese Migrant Workers

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/963482307/iron-moon-the-poetry-of-chinese-migrant-workers/description

Lunpeng Ma

Crowdfunding Synopsis

This documentary film follows the lives of workers behind the rise of Chinese manufacturing. Their stories and poetry affect us all, and with your help, we can bring this important film to the US and publish a corresponding poetry anthology.

What does "IRON MOON" mean?

Few of us have stopped to consider the lives of the workers who manufacture the objects that make up our daily lives. I’m typing this on my Mac, with an iPhone at my elbow. We use these objects without knowing anything about the Foxconn plants in which they are made, or even where these factories are located, let alone who works in them. One such worker was the young Chinese poet Xu Lizhi, who, at the age of 24, jumped out of a building not far from where he worked at the Foxconn factory in Shenzhen. After Xu’s death in the fall of 2014, the international media got a hold of the story and recognized its importance as a symbol of our time. Time Magazine put out an article titled “The Poet Who Died for Your Phone,” and the largest daily German newspaper, Süddeutsche Zeitung, published an article claiming that global companies were taking advantage of less developed countries like China and India, producing products under exploitative conditions and taking the vast majority of the profit. Before he died, Xu Lizhi wrote a powerful poem from which the title of the film and anthology is taken:

I Swallowed an Iron Moon

I swallowed an iron moon

they called it a screw

I swallowed industrial wastewater and unemployment forms

bent over machines, our youth died young

I swallowed labor, I swallowed poverty

swallowed pedestrian bridges, swallowed this rusted-out life

I can’t swallow any more

everything I’ve swallowed roils up in my throat

I spread across my country a poem of shame

About the Documentary Film

The poem above speaks for many workers who find themselves “screws” in the machine, or just cogs in the larger global production system. There are a shocking number of these workers, and a few of them, like Xu Lizhi, manage to write about their experiences in deeply moving ways. Iron Moon follows five of these worker-poets through their daily lives, showing the pressures of their work, and the poverty in which many of them survive. And certainly, not all of them are factory workers.

<9b44b234c48ac368eb7f67761b508955_h264_high.jpg> PLAY

-The day before the National Day, 24-year-old Xu Lizhi jumped out of a building. He was working on Foxconn assembly line, the world’s largest Apple manufacturing factory. He left behind a volume of painful poems of the highest quality.

<844bbf6f028a7b855b8ac4b9a1c44894_h264_high.jpg> PLAY

-Lucky (Chen Nianxi), demolitions worker for 16 years. His daily routine is used to blow up rocks and dig mines for miners. By lonely, deep mountains, he writes poetry filled with a fighting spirit. Learning that his mother is ill with terminal cancer, he chooses to stay in the mountains and continue doing this dangerous work rather than returning home. He uses his own life’s energy to help continue hers.

<17e65fd3c354f8bf6b64d3c2134c277e_h264_high.jpg> PLAY

-Old Coalminer (Lao Jing), coalmine worker for 25 years. The taciturn worker-poet Old Coalminer perches in an 800-meter-deep coalmine. His poetry takes shape in this difficult, dark environment. His poems speak with the center of the earth, speak with the coal beds. After a fatal mine disaster, his poetry can also speak with the dead.

PLAY

-Dawn (Wu Xia), a worker since age 14. The garment factory worker Dawn is a "pearl surviving at the bottom." She loves sundresses, and she keeps many cheap, beat-up sundresses in her wardrobe. Even though her life is difficult, she keeps up her spirits and love of beauty, writing poems that explore the strength of the human spirit.

PLAY

-Blackbird (Wu Niaoniao), unemployed assembly line worker. In Blackbird’s hometown hospital, he cuts the umbilical cord of his second child, whose birth is illegal under the one-child policy. Just a month before, he won an important poetry award for his unique style, and he feels doubly blessed. When he loses his job and must go back to the city to find a new one, however, everything begins to fall apart.

These are the people who make up the documentary film, and whose work has been anthologized in the book Iron Moon.

In our inexorably globalizing and interconnected world, these stories are essential to understanding not only others, but basic elements of our own lives. The shoes we wear, the electronics we use, the food we eat, the materials that make up our homes, are produced by others, and frequently those others live across the world from us. Their stories form a significant of our own stories.

Looking Toward the Future

Iron Moon is the first in a series of three documentary films and three corresponding anthologies of poetry that will continue the stories of the first. Iron Moon has already won major film awards in China and Taiwan, and been shown more than 700 times across 130 cities. In online forums and messaging apps alone, discussion of the film has reached more than 80 million people. It’s fair to say that with their first film, and without the support of major distribution or box office profits, filmmakers Qin Xiaoyu and Wu Feiyu have created a true cultural phenomenon in China.

<129693069842285394d5491fc265d0fd_original.jpg>

The next step is to bring the film to the United States. The American premier of Iron Moon will take place in early November, and the ultimate dream is to make it to the Oscars. The filmmakers will travel to the States to show the film in NYC and Los Angeles, as well as at major universities across the US, and to join in active discussions with viewers, students, and anyone interested in these incredible stories. The poetry anthology will be published by the prestigious literary publisher White Pine Press at the same time.

But all of these plans require financing, and as part of a small independent film company, the filmmakers can use all of the help they can get. If you think these voices should be brought into the larger international conversation, if you’re interested in Chinese culture and poetry, or if you use an iPhone, buy products that are made in China, or understand that globalism is effecting all of us, please consider supporting this film and poetry anthology.

All funds will go toward:

The translation and publication of the Iron Moon poetry anthology;

Transportation and accommodation for the film team on their US tour, including showings and discussions in New Haven, Boston, New York, Durham, San Francisco and Los Angeles.

The Team

<320f3fec42c8db6904e964d7048c0228_original.jpg>

Eleanor Goodman, translator of Iron Moon. Goodman is a Research Associate at the Fairbank Center at Harvard University, and spent a year at Peking University on a Fulbright Fellowship. She has been an artist in residence at the American Academy in Rome and was awarded a Henry Luce Translation Fellowship from the Vermont Studio Center. Her first book of translations, Something Crosses My Mind: Selected Poems of Wang Xiaoni (Zephyr Press, 2014) was the recipient of a 2013 PEN/Heim Translation Grant and winner of the 2015 Lucien Stryk Prize. The book was also shortlisted for the International Griffin Prize. Her first poetry book, Nine Dragon Island, was a finalist for the Drunken Boat First Book Prize.

"As a poet and translator of Chinese poetry, I’ve spent a lot of time interacting with Chinese poets and bringing their work into English. Poetry at its best is the most profound form of communication, a multifaceted mirror that first and foremost shows us to ourselves. It is also a tool by which we can gain an understanding of lives that are different or distant from our own. With that in mind, I’m very excited to be part of a project that is bringing the recent Chinese documentary Iron Moon, along with an anthology of contemporary poetry of the same name (translated by yours truly), to the United States. The documentary centers on workers at the bottom rungs of Chinese society, workers who also write poetry about their experiences in places most of us will likely never see in person. It is a rare example of the best artistic productions happening in China today: honest, revealing, powerful, and full of surprising glimpses into our current globalized world."

<2a010d0b7cced1686d518df250d226dc_original.jpg>

Xiaoyu Qin, director of Iron Moon. He is also a poet, writer, poem critic, chair of Zurong Dialect Film Festival Committee, jury of Beijing Huayi International Chinese Poetry Competition. Publication works includes: 1970 Notes on Poetry, Qin Xiaoyu Album (16th Period of New Poetry Collection ) , Jade Ladder: Contemporary Chinese Poetry (Monograph on Poetics), Selected Essays of Ma Yan, Today: Selected Novel of Ma Yan.

Feiyue Wu, director of Iron Moon. His other works include: Surge: 1978-2008, Fortune and Dream: Twenty Years of Chinese Stock Market, and Renminbi.

<4c4dfaaa48be2ed63746f8a5e4ab51e8_original.jpg>

Qingzeng Cai, producer of Iron Moon. His case study of Iron Moon has been enclosed in China Documentary Report and Idoc database.

<988b0bacd2f86cec2ebd6ba6efbe4787_original.jpg>

Xiaobo Wu, co-Producer of Iron Moon. A famous financial writer in China, EMBA course professor of SJTU and JNU , working on corporate study. He was evaluated as “Chinese Youth Leader” in 2009 by Southern People Weekly. Representative works are: The Big Failures, Thirty Years of Surge, Hundred years of Ups and Downs, Two Thousand years of Mighty.

Dr. Lunpeng Ma, he has been an active cultural critic and founder of a series of cultural activities across the Pacific. He is now help the production team of Iron Moon to promote this documentary and get the crowdfunding from Kickstarter.

***

To know more about this project, please visit the film official website: http://www.ironmoonmovie.com

ron Moon-The Poet Who Died For Your Phone

http://time.com/chinapoet/

Hundreds of thousands of people travel from China’s countryside to its cities to work in factories, building devices for international consumers and trying to assemble better lives for themselves. Xu Lizhi left behind a haunting record of that life

By Emily Rauhala / Shenzhen and Jieyang

He dreamed about it, wrote about it. He rolled it around in the palm of his hand. Working through the “dark night of overtime” in January 2014, the 23-year-old Xu Lizhi imagined himself like a misplaced screw, “plunging vertically, lightly clinking,” lost to the factory floor. “It won’t attract anyone’s attention,” he wrote. “Just like the last time/ On a night like this/ When someone plunged to the ground.”

A village boy with clothes-hanger shoulders and a high school education, Xu moved to the southern Chinese city of Shenzhen in 2011. He was looking for a way out of rural life; he hoped to find a way to use his mind. Like hundreds of thousands before him, he settled, to start, for a spot on the assembly line at Foxconn Technology Group, the Taiwan manufacturing giant linked to just about every other name in electronics, from Apple to Acer and Microsoft. To make sense of what he saw there, he started to write, his evocative work earning him a modest following in the city’s small community of dagong shiren, or migrant poets.

In his 3½ years in Shenzhen, Xu captured life there in brutal, beautiful detail. In the city, the country kid found a voice that roared, publishing poems in company newspaper Foxconn People and sharing his work online. Factory workers are often treated as interchangeable, anonymous. To readers, his words were a reminder that every laborer has a mind and heart; for him, writing was a way out. “Writing poems gives me another way of life,” he told a Chinese journalist in an unpublished interview that TIME has seen. “When you’re writing poems, you’re not confined to the real world.” For the first time, Xu’s brother and close friends shared his story with the foreign press.

Translation by The Nao Project at libcom.org.

In the factory city, 2011 was a sad and strange time. The complex known as Longhua is home to some 100,000 workers from across China. In 2010, at least 17 attempted suicide; 14 died. Thanks to confidentiality clauses and tight security, it was hard to know what was happening on the inside. Labor groups blamed working conditions: long hours, modest pay and mindless, repetitive work. The late Steve Jobs, a major customer, called the deaths “troubling” but noted that the suicide rate was lower than the U.S. average. Foxconn countered that conditions were fine. To dissuade jumpers, it hung nets from the dorm — a macabre spectacle that made headlines around the world. “The company places a priority on ensuring the welfare of all of our over one million employees across all of our operations globally,” Foxconn said in a statement to TIME. “… Our record of progress is very clear and the significant enhancements in our company’s working conditions have been confirmed by external audit groups.”

Though consumer activism in the 1990s and 2000s called global attention to sweatshop conditions in Guangdong’s sneaker factories, the lives of China’s migrant laborers have long since faded from view. Outside activist circles, many accepted the notion that young workers were cheerfully trading their youth for a better livelihood. They imagined that they, like the rest of China, were rushing unambivalently toward consumer capitalism, saving their factory wages for ever-newer, shinier phones.

That, of course, was only part of the story. The great economic experiment orchestrated by Mao Zedong’s heirs paved the way for more than 35 years of growth and profound social transformation. Textbooks credit these cadres with “lifting” hundreds of millions out of poverty, but it was ordinary Chinese like Xu who toiled their way to lives that their parents could not have imagined. Now the days of double-digit GDP growth are over, and state-led “socialism with Chinese characteristics“ has spawned one of the most stratified societies on earth. People no longer march in unison — some jump forward, others fall back.

In the years Xu spent in Shenzhen, several more migrants jumped to their death. Xu himself never made the leap to the life he imagined — to a desk job, a chance to think, and the means to make his family proud. He stopped believing that people were listening. That things could change. On Sept. 30, 2014, eight months after he imagined himself plunging, Xu Lizhi stepped off the ledge.

Chasing Fortune

When Xu left his village outside the city of Jieyang he tread a well-worn path. The people of eastern Guangdong province have been on the move for centuries, sailing south to find work in the trading ports of Southeast Asia, or slipping across the border to try their luck in Hong Kong. The area, known as Chaoshan, is famous in China as the birthplace of businesspeople.

By the time Xu was born, in July 1990, Chaoshan’s strivers were moving west, to the Pearl River Delta, where a great economic experiment was under way. A former fishing village, Shenzhen, was morphing into a manufacturing hub and there was money to be made. Most of the work was brutal and poorly paid, but some struck it rich. “In our village, people dropped out early to go to the city,” said Xu Hongzhi, Xu Lizhi’s oldest brother, over dinner in Jieyang. “All anyone could talk about at the spring festival was who would make it big next year.”

Xu Lizhi seemed destined to join the great migration. He was the youngest of three sons born to parents that farmed rice, leeks and taro on a modest plot. His oldest brother remembers him as shy kid unsuited to farm work, a boy who loved reading but had limited access to books. (There was no library or bookstore; his parents did not read.) In high school, when he should have been cramming, he was busy watching TV talent shows, Xu Hongzhi says. Xu Lizhi’s favorite, an extravaganza called Super Boy, plucked ordinary people from obscurity and made them stars.

Translation by The Nao Project at libcom.org.

Xu Lizhi hoped to shine a little brighter by getting into university, but his scores on the national entrance exam fell short, a failure that haunted him, according to his brother and two friends. His family urged him forward: in their village, marrying off a son meant buying a home — they needed to save for three. Xu Hongzhi told his little brother to forget about the exam and follow his classmates to the city. “I said to him, ‘What’s in the past is in the past, work hard and you can still change your fate.’”

And until the end, the family believed he would.

Bright Lights, Big City

For a curious young man, Shenzhen has much to offer. The city of 7 million pulses with people from every place and province (and no shortage of bookstores). In the 2013 “I Speak of Blood,” Xu Lizhi captured the teeming cosmopolitanism of his adopted home, observing from his “matchbox” room a mix of: “Stray women in long-distance marriages/ Sichuan chaps selling mala soup/ Old ladies from Henan running stands/ And me with my eyes open all night to write a poem/ After running about all day to make a living.”

Making a living was an almost all-consuming task, an act of endurance that wore at his body and tore at his mind. At his first factory job at Foxconn, Xu alternated each month between day and night shifts, spending long, restless hours on his feet. Though he told a friend he got used to the pain, his poems ache with anguish. “By the assembly line I stood straight like iron, hands like flight,” he wrote in August 2011. “How many days, how many nights/ Did I — just like that — standing, fall asleep?”

Factory life made Xu feel like a machine, a half-human with a “stomach forged of iron/ full of thick acid, sulfuric and nitric.” The same jig that forced workers’ “skin to peel” replaced their human tissue with a “layer of aluminum alloy.” He felt dehumanized, stunted, as if the work itself was stealing his ability to conjure language beyond “working words” like “workshop, assembly line, machine, work card, overtime, wages …”

The world of words was his only respite. On his rare days off, Xu liked to visit bookstores, lingering in the aisles, friends say. He also frequented the factory library, and met writers and editors involved in the company newspaper and started writing poems and reviews for it. “I was very excited when I first saw his work,” says an editor familiar with his early work who asked to remain anonymous to protect his job. “It made my eyes widen.”

Xu started publishing poems online and submitting his work to small magazines. He also connected with fellow worker-poets in the Pearl River Delta, both in person and online. One Sunday in the spring of 2012, he took the bus to the neighboring city of Guangzhou to attend a gathering. A fellow writer, Gao, noticed a thin young man sitting on the sidelines, listening while staring at his phone. Gao asked him to join the group. Reluctantly, he did.

Reuters

Scenes from within Foxconn factory, cafeteria and dormitory in Shenzhen.

Afterward, Gao walked Xu to the station. While they waited for the Shenzhen-bound bus, they shared a meal and a drink. They were both 20-something migrants in jobs they despised, sensitive men in a city that rewarded the brash. Xu told Gao he felt trapped, unhappy with his job but unable to secure another. “Lizhi knew he should be using a pen and not a hammer,” Gao says. “But there was a gap between reality and his dreams.”

Eating Bitterness

By 2013, Xu felt like the city might swallow him. He traded the factory dorm for a small, rented room, but the space started to feel like a coffin. Some days, he longed to write like the Tang dynasty greats, soaking his words in wine and beauty, musing about the play of “the moon on snow.” Sleepless, stifled, he could not. “This reality,” he wrote, “only lets me speak of blood.”

Translation by The Nao Project at libcom.org.

Xu managed to switch from the assembly line to the logistics department, a job that gave him a bit more variety and the occasional chance to play on his phone, he told friends. But the new job did little to quell his anxiety, and death began to haunt his work. In “A Kind of Prophecy” he compared himself to his grandfather, a thin man who “swallowed his feelings” and died young. “In the autumn of 1943, the Japanese devils invaded/ and burned my grandfather alive/ at the age of 23/ This year I turn 23.”

Xu said nothing of his struggle to his family, and little to his friends. When he phoned home, he only shared good news, his oldest brother Xu Hongzhi says. His family had no idea he wrote. Xu Lizhi told a Chinese journalist he was certain they would not understand. “On one hand, they cannot understand poetry,” Xu said. “On the other I sometimes mention unpleasant experience, and I don’t want them to worry.”

The people around him believed a certain amount of suffering was normal, even necessary. Ask a veteran of Shenzhen’s factories about their early years, and, odds are, they will speak with pride about “eating bitterness,” a Chinese phrase that suggests an ability to endure. Born to parents who knew famine, earlier migrants moved from abject poverty on the farm to deadly sweatshops in the city. Those who survived have a tendency to see new arrivals as lacking resolve: a kids-these-days thing.

Xu Hongzhi and the editor who asked not to be named, had both, like millions before them, moved to the city as teenagers, toiled in tough conditions, and come out stronger. They believed Xu Lizhi would do the same if he just waited and worked. When he looked at Xu, the editor saw talent, not despair. “Things today are so much better than they used to be,” he says. “But I guess today’s generation has different needs and expectations.”

Xu alternated between hope and hopelessness. He dared to hope for respite from monotony and a chance to use his talent, and twice summoned the courage to apply, unsuccessfully, for desk jobs — as a librarian at the factory, and at his favorite Shenzhen bookstore Youyi. But when a local journalist asked him about his future, he said he could not expect too much: “We all hope our lives will become better and better, but most of us don’t control our destiny.”

Epilogue

As spring festival approached in 2014, Xu left his job at Foxconn without telling his family, his brother said. He told friends he was off to the city of Suzhou not far from Shanghai to see a girl and start afresh. It is unclear where he spent that spring and summer; he lost touch with several close friends, but paid his Shenzhen rent, his brother says.

In late September he re-emerged in Shenzhen and signed a new contract with Foxconn. Two days later, on the eve of China’s Oct. 1 National Day holiday, Xu Lizhi, by then 24, walked to a mall across from his favorite bookstore, took the elevator to the 17th floor, and jumped to his death. It was not until the news of another suicide broke that friends found his final poems and a post scheduled to publish on Oct.1: “A new day,” it read.

In the wake of his death, labor groups translated Xu’s work into English, leading to notices in Bloomberg News and the Washington Post. Chinese poet Qin Xiaoyu is making a documentary film about Xu’s life and work. He also published a slim volume of his poems. Foxconn, citing company policy, declined to answer specific questions about Xu.

Xu Hongzhi took the long-distance bus from Jieyang to negotiate a settlement with the company. Unable to take Xu Lizhi back to the village, he carried his brother’s ashes to the coast and scattered them in the sea. Zhou Qizao, a fellow worker-poet, penned a defiant tribute: “Another screw comes loose/ Another migrant worker brother jumps/ You die in place of me/ And I keep writing in place of you.”

— With reporting by Gu Yongqiang

If you or a loved one has suicidal thoughts, call 1-800-273-8255 or visit suicidepreventionlifeline.org.

Risks and challenges

Regardless of any outcome of this crowdfunding for our documentary Iron Moon, we are determined to screen it to the American public so that everyone gets a chance to watch this remarkable film. Due to very limited time, we need to prepay all the costs out of our own pockets before the crowdfunding campaign. Without your critical support and if the crowdfunding fails to achieve our goal, we have to take this financial burden, which will make it almost impossible for us to produce the next part of this trilogy.

NO. We are not in the process of completing any past project. The successful crowdfunding will actually make Iron Moon visible to Americans and help us start the second and third part of this making a trilogy dedicated to Chinese workers and their poems.

Learn about accountability on Kickstarter

FAQ

Have a question? If the info above doesn't help, you can ask the project creator directly.

Ask a question

Report this project to Kickstarter

Iron Moon: The Poetry of Chinese Migrant Workers

A documentary film directed by Xiaoyu Qin and Feiyue Wu followed by a discussion with the directors and reading by poet Chen Nianxi (陳年喜), who is a demolitions worker and poet for 16 years

Saturday November 19, 2016 7:00 PM

ILWU Local 34

801 2nd St. San Francisco

Sponsored by

LaborFest

http://www.laborfest.net

(415)642-8066

laborfest [at] laborfest.net

For reservations contact LaborFest

About the documentary film:

An assembly line worker in an Apple factory who commits suicide at the young age of 24, leaving behind 200 poems of despair—“I swallowed an iron moon…..”; a guileless lathe operator who is rebuffed at every turn, living in the world of his poetry; a female clothing factory worker who lives in poverty but writes poetry rich in dignity and love; a coalminer who works deep in the earth year round, trying to contact and make peace with the spirits of his dead coworkers through his poetry; and a goldmine demolitions worker who blasts rocks several kilometers into mountainsides to support his family, while writing poetry to carry the weight of his fury and affections—“My body carries three tons of dynamite….” They could be any of the 350 million workers in China, and yet these five are also poets. Using poetry as a tool to chip away at the ice of silence, they express the hidden life stories and experiences of people living at the bottom of the society. This is one story behind the sudden rise of China, and a mournful song of global capitalism.

Iron Moon: The Poetry of Chinese Migrant Workers

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/963482307/iron-moon-the-poetry-of-chinese-migrant-workers/description

Lunpeng Ma

Crowdfunding Synopsis

This documentary film follows the lives of workers behind the rise of Chinese manufacturing. Their stories and poetry affect us all, and with your help, we can bring this important film to the US and publish a corresponding poetry anthology.

What does "IRON MOON" mean?

Few of us have stopped to consider the lives of the workers who manufacture the objects that make up our daily lives. I’m typing this on my Mac, with an iPhone at my elbow. We use these objects without knowing anything about the Foxconn plants in which they are made, or even where these factories are located, let alone who works in them. One such worker was the young Chinese poet Xu Lizhi, who, at the age of 24, jumped out of a building not far from where he worked at the Foxconn factory in Shenzhen. After Xu’s death in the fall of 2014, the international media got a hold of the story and recognized its importance as a symbol of our time. Time Magazine put out an article titled “The Poet Who Died for Your Phone,” and the largest daily German newspaper, Süddeutsche Zeitung, published an article claiming that global companies were taking advantage of less developed countries like China and India, producing products under exploitative conditions and taking the vast majority of the profit. Before he died, Xu Lizhi wrote a powerful poem from which the title of the film and anthology is taken:

I Swallowed an Iron Moon

I swallowed an iron moon

they called it a screw

I swallowed industrial wastewater and unemployment forms

bent over machines, our youth died young

I swallowed labor, I swallowed poverty

swallowed pedestrian bridges, swallowed this rusted-out life

I can’t swallow any more

everything I’ve swallowed roils up in my throat

I spread across my country a poem of shame

About the Documentary Film

The poem above speaks for many workers who find themselves “screws” in the machine, or just cogs in the larger global production system. There are a shocking number of these workers, and a few of them, like Xu Lizhi, manage to write about their experiences in deeply moving ways. Iron Moon follows five of these worker-poets through their daily lives, showing the pressures of their work, and the poverty in which many of them survive. And certainly, not all of them are factory workers.

<9b44b234c48ac368eb7f67761b508955_h264_high.jpg> PLAY

-The day before the National Day, 24-year-old Xu Lizhi jumped out of a building. He was working on Foxconn assembly line, the world’s largest Apple manufacturing factory. He left behind a volume of painful poems of the highest quality.

<844bbf6f028a7b855b8ac4b9a1c44894_h264_high.jpg> PLAY

-Lucky (Chen Nianxi), demolitions worker for 16 years. His daily routine is used to blow up rocks and dig mines for miners. By lonely, deep mountains, he writes poetry filled with a fighting spirit. Learning that his mother is ill with terminal cancer, he chooses to stay in the mountains and continue doing this dangerous work rather than returning home. He uses his own life’s energy to help continue hers.

<17e65fd3c354f8bf6b64d3c2134c277e_h264_high.jpg> PLAY

-Old Coalminer (Lao Jing), coalmine worker for 25 years. The taciturn worker-poet Old Coalminer perches in an 800-meter-deep coalmine. His poetry takes shape in this difficult, dark environment. His poems speak with the center of the earth, speak with the coal beds. After a fatal mine disaster, his poetry can also speak with the dead.

PLAY

-Dawn (Wu Xia), a worker since age 14. The garment factory worker Dawn is a "pearl surviving at the bottom." She loves sundresses, and she keeps many cheap, beat-up sundresses in her wardrobe. Even though her life is difficult, she keeps up her spirits and love of beauty, writing poems that explore the strength of the human spirit.

PLAY

-Blackbird (Wu Niaoniao), unemployed assembly line worker. In Blackbird’s hometown hospital, he cuts the umbilical cord of his second child, whose birth is illegal under the one-child policy. Just a month before, he won an important poetry award for his unique style, and he feels doubly blessed. When he loses his job and must go back to the city to find a new one, however, everything begins to fall apart.

These are the people who make up the documentary film, and whose work has been anthologized in the book Iron Moon.

In our inexorably globalizing and interconnected world, these stories are essential to understanding not only others, but basic elements of our own lives. The shoes we wear, the electronics we use, the food we eat, the materials that make up our homes, are produced by others, and frequently those others live across the world from us. Their stories form a significant of our own stories.

Looking Toward the Future

Iron Moon is the first in a series of three documentary films and three corresponding anthologies of poetry that will continue the stories of the first. Iron Moon has already won major film awards in China and Taiwan, and been shown more than 700 times across 130 cities. In online forums and messaging apps alone, discussion of the film has reached more than 80 million people. It’s fair to say that with their first film, and without the support of major distribution or box office profits, filmmakers Qin Xiaoyu and Wu Feiyu have created a true cultural phenomenon in China.

<129693069842285394d5491fc265d0fd_original.jpg>

The next step is to bring the film to the United States. The American premier of Iron Moon will take place in early November, and the ultimate dream is to make it to the Oscars. The filmmakers will travel to the States to show the film in NYC and Los Angeles, as well as at major universities across the US, and to join in active discussions with viewers, students, and anyone interested in these incredible stories. The poetry anthology will be published by the prestigious literary publisher White Pine Press at the same time.

But all of these plans require financing, and as part of a small independent film company, the filmmakers can use all of the help they can get. If you think these voices should be brought into the larger international conversation, if you’re interested in Chinese culture and poetry, or if you use an iPhone, buy products that are made in China, or understand that globalism is effecting all of us, please consider supporting this film and poetry anthology.

All funds will go toward:

The translation and publication of the Iron Moon poetry anthology;

Transportation and accommodation for the film team on their US tour, including showings and discussions in New Haven, Boston, New York, Durham, San Francisco and Los Angeles.

The Team

<320f3fec42c8db6904e964d7048c0228_original.jpg>

Eleanor Goodman, translator of Iron Moon. Goodman is a Research Associate at the Fairbank Center at Harvard University, and spent a year at Peking University on a Fulbright Fellowship. She has been an artist in residence at the American Academy in Rome and was awarded a Henry Luce Translation Fellowship from the Vermont Studio Center. Her first book of translations, Something Crosses My Mind: Selected Poems of Wang Xiaoni (Zephyr Press, 2014) was the recipient of a 2013 PEN/Heim Translation Grant and winner of the 2015 Lucien Stryk Prize. The book was also shortlisted for the International Griffin Prize. Her first poetry book, Nine Dragon Island, was a finalist for the Drunken Boat First Book Prize.

"As a poet and translator of Chinese poetry, I’ve spent a lot of time interacting with Chinese poets and bringing their work into English. Poetry at its best is the most profound form of communication, a multifaceted mirror that first and foremost shows us to ourselves. It is also a tool by which we can gain an understanding of lives that are different or distant from our own. With that in mind, I’m very excited to be part of a project that is bringing the recent Chinese documentary Iron Moon, along with an anthology of contemporary poetry of the same name (translated by yours truly), to the United States. The documentary centers on workers at the bottom rungs of Chinese society, workers who also write poetry about their experiences in places most of us will likely never see in person. It is a rare example of the best artistic productions happening in China today: honest, revealing, powerful, and full of surprising glimpses into our current globalized world."

<2a010d0b7cced1686d518df250d226dc_original.jpg>

Xiaoyu Qin, director of Iron Moon. He is also a poet, writer, poem critic, chair of Zurong Dialect Film Festival Committee, jury of Beijing Huayi International Chinese Poetry Competition. Publication works includes: 1970 Notes on Poetry, Qin Xiaoyu Album (16th Period of New Poetry Collection ) , Jade Ladder: Contemporary Chinese Poetry (Monograph on Poetics), Selected Essays of Ma Yan, Today: Selected Novel of Ma Yan.

Feiyue Wu, director of Iron Moon. His other works include: Surge: 1978-2008, Fortune and Dream: Twenty Years of Chinese Stock Market, and Renminbi.

<4c4dfaaa48be2ed63746f8a5e4ab51e8_original.jpg>

Qingzeng Cai, producer of Iron Moon. His case study of Iron Moon has been enclosed in China Documentary Report and Idoc database.

<988b0bacd2f86cec2ebd6ba6efbe4787_original.jpg>

Xiaobo Wu, co-Producer of Iron Moon. A famous financial writer in China, EMBA course professor of SJTU and JNU , working on corporate study. He was evaluated as “Chinese Youth Leader” in 2009 by Southern People Weekly. Representative works are: The Big Failures, Thirty Years of Surge, Hundred years of Ups and Downs, Two Thousand years of Mighty.

Dr. Lunpeng Ma, he has been an active cultural critic and founder of a series of cultural activities across the Pacific. He is now help the production team of Iron Moon to promote this documentary and get the crowdfunding from Kickstarter.

***

To know more about this project, please visit the film official website: http://www.ironmoonmovie.com

ron Moon-The Poet Who Died For Your Phone

http://time.com/chinapoet/

Hundreds of thousands of people travel from China’s countryside to its cities to work in factories, building devices for international consumers and trying to assemble better lives for themselves. Xu Lizhi left behind a haunting record of that life

By Emily Rauhala / Shenzhen and Jieyang

He dreamed about it, wrote about it. He rolled it around in the palm of his hand. Working through the “dark night of overtime” in January 2014, the 23-year-old Xu Lizhi imagined himself like a misplaced screw, “plunging vertically, lightly clinking,” lost to the factory floor. “It won’t attract anyone’s attention,” he wrote. “Just like the last time/ On a night like this/ When someone plunged to the ground.”

A village boy with clothes-hanger shoulders and a high school education, Xu moved to the southern Chinese city of Shenzhen in 2011. He was looking for a way out of rural life; he hoped to find a way to use his mind. Like hundreds of thousands before him, he settled, to start, for a spot on the assembly line at Foxconn Technology Group, the Taiwan manufacturing giant linked to just about every other name in electronics, from Apple to Acer and Microsoft. To make sense of what he saw there, he started to write, his evocative work earning him a modest following in the city’s small community of dagong shiren, or migrant poets.

In his 3½ years in Shenzhen, Xu captured life there in brutal, beautiful detail. In the city, the country kid found a voice that roared, publishing poems in company newspaper Foxconn People and sharing his work online. Factory workers are often treated as interchangeable, anonymous. To readers, his words were a reminder that every laborer has a mind and heart; for him, writing was a way out. “Writing poems gives me another way of life,” he told a Chinese journalist in an unpublished interview that TIME has seen. “When you’re writing poems, you’re not confined to the real world.” For the first time, Xu’s brother and close friends shared his story with the foreign press.

Translation by The Nao Project at libcom.org.

In the factory city, 2011 was a sad and strange time. The complex known as Longhua is home to some 100,000 workers from across China. In 2010, at least 17 attempted suicide; 14 died. Thanks to confidentiality clauses and tight security, it was hard to know what was happening on the inside. Labor groups blamed working conditions: long hours, modest pay and mindless, repetitive work. The late Steve Jobs, a major customer, called the deaths “troubling” but noted that the suicide rate was lower than the U.S. average. Foxconn countered that conditions were fine. To dissuade jumpers, it hung nets from the dorm — a macabre spectacle that made headlines around the world. “The company places a priority on ensuring the welfare of all of our over one million employees across all of our operations globally,” Foxconn said in a statement to TIME. “… Our record of progress is very clear and the significant enhancements in our company’s working conditions have been confirmed by external audit groups.”

Though consumer activism in the 1990s and 2000s called global attention to sweatshop conditions in Guangdong’s sneaker factories, the lives of China’s migrant laborers have long since faded from view. Outside activist circles, many accepted the notion that young workers were cheerfully trading their youth for a better livelihood. They imagined that they, like the rest of China, were rushing unambivalently toward consumer capitalism, saving their factory wages for ever-newer, shinier phones.

That, of course, was only part of the story. The great economic experiment orchestrated by Mao Zedong’s heirs paved the way for more than 35 years of growth and profound social transformation. Textbooks credit these cadres with “lifting” hundreds of millions out of poverty, but it was ordinary Chinese like Xu who toiled their way to lives that their parents could not have imagined. Now the days of double-digit GDP growth are over, and state-led “socialism with Chinese characteristics“ has spawned one of the most stratified societies on earth. People no longer march in unison — some jump forward, others fall back.

In the years Xu spent in Shenzhen, several more migrants jumped to their death. Xu himself never made the leap to the life he imagined — to a desk job, a chance to think, and the means to make his family proud. He stopped believing that people were listening. That things could change. On Sept. 30, 2014, eight months after he imagined himself plunging, Xu Lizhi stepped off the ledge.

Chasing Fortune

When Xu left his village outside the city of Jieyang he tread a well-worn path. The people of eastern Guangdong province have been on the move for centuries, sailing south to find work in the trading ports of Southeast Asia, or slipping across the border to try their luck in Hong Kong. The area, known as Chaoshan, is famous in China as the birthplace of businesspeople.

By the time Xu was born, in July 1990, Chaoshan’s strivers were moving west, to the Pearl River Delta, where a great economic experiment was under way. A former fishing village, Shenzhen, was morphing into a manufacturing hub and there was money to be made. Most of the work was brutal and poorly paid, but some struck it rich. “In our village, people dropped out early to go to the city,” said Xu Hongzhi, Xu Lizhi’s oldest brother, over dinner in Jieyang. “All anyone could talk about at the spring festival was who would make it big next year.”

Xu Lizhi seemed destined to join the great migration. He was the youngest of three sons born to parents that farmed rice, leeks and taro on a modest plot. His oldest brother remembers him as shy kid unsuited to farm work, a boy who loved reading but had limited access to books. (There was no library or bookstore; his parents did not read.) In high school, when he should have been cramming, he was busy watching TV talent shows, Xu Hongzhi says. Xu Lizhi’s favorite, an extravaganza called Super Boy, plucked ordinary people from obscurity and made them stars.

Translation by The Nao Project at libcom.org.

Xu Lizhi hoped to shine a little brighter by getting into university, but his scores on the national entrance exam fell short, a failure that haunted him, according to his brother and two friends. His family urged him forward: in their village, marrying off a son meant buying a home — they needed to save for three. Xu Hongzhi told his little brother to forget about the exam and follow his classmates to the city. “I said to him, ‘What’s in the past is in the past, work hard and you can still change your fate.’”

And until the end, the family believed he would.

Bright Lights, Big City

For a curious young man, Shenzhen has much to offer. The city of 7 million pulses with people from every place and province (and no shortage of bookstores). In the 2013 “I Speak of Blood,” Xu Lizhi captured the teeming cosmopolitanism of his adopted home, observing from his “matchbox” room a mix of: “Stray women in long-distance marriages/ Sichuan chaps selling mala soup/ Old ladies from Henan running stands/ And me with my eyes open all night to write a poem/ After running about all day to make a living.”

Making a living was an almost all-consuming task, an act of endurance that wore at his body and tore at his mind. At his first factory job at Foxconn, Xu alternated each month between day and night shifts, spending long, restless hours on his feet. Though he told a friend he got used to the pain, his poems ache with anguish. “By the assembly line I stood straight like iron, hands like flight,” he wrote in August 2011. “How many days, how many nights/ Did I — just like that — standing, fall asleep?”

Factory life made Xu feel like a machine, a half-human with a “stomach forged of iron/ full of thick acid, sulfuric and nitric.” The same jig that forced workers’ “skin to peel” replaced their human tissue with a “layer of aluminum alloy.” He felt dehumanized, stunted, as if the work itself was stealing his ability to conjure language beyond “working words” like “workshop, assembly line, machine, work card, overtime, wages …”

The world of words was his only respite. On his rare days off, Xu liked to visit bookstores, lingering in the aisles, friends say. He also frequented the factory library, and met writers and editors involved in the company newspaper and started writing poems and reviews for it. “I was very excited when I first saw his work,” says an editor familiar with his early work who asked to remain anonymous to protect his job. “It made my eyes widen.”

Xu started publishing poems online and submitting his work to small magazines. He also connected with fellow worker-poets in the Pearl River Delta, both in person and online. One Sunday in the spring of 2012, he took the bus to the neighboring city of Guangzhou to attend a gathering. A fellow writer, Gao, noticed a thin young man sitting on the sidelines, listening while staring at his phone. Gao asked him to join the group. Reluctantly, he did.

Reuters

Scenes from within Foxconn factory, cafeteria and dormitory in Shenzhen.

Afterward, Gao walked Xu to the station. While they waited for the Shenzhen-bound bus, they shared a meal and a drink. They were both 20-something migrants in jobs they despised, sensitive men in a city that rewarded the brash. Xu told Gao he felt trapped, unhappy with his job but unable to secure another. “Lizhi knew he should be using a pen and not a hammer,” Gao says. “But there was a gap between reality and his dreams.”

Eating Bitterness

By 2013, Xu felt like the city might swallow him. He traded the factory dorm for a small, rented room, but the space started to feel like a coffin. Some days, he longed to write like the Tang dynasty greats, soaking his words in wine and beauty, musing about the play of “the moon on snow.” Sleepless, stifled, he could not. “This reality,” he wrote, “only lets me speak of blood.”

Translation by The Nao Project at libcom.org.

Xu managed to switch from the assembly line to the logistics department, a job that gave him a bit more variety and the occasional chance to play on his phone, he told friends. But the new job did little to quell his anxiety, and death began to haunt his work. In “A Kind of Prophecy” he compared himself to his grandfather, a thin man who “swallowed his feelings” and died young. “In the autumn of 1943, the Japanese devils invaded/ and burned my grandfather alive/ at the age of 23/ This year I turn 23.”

Xu said nothing of his struggle to his family, and little to his friends. When he phoned home, he only shared good news, his oldest brother Xu Hongzhi says. His family had no idea he wrote. Xu Lizhi told a Chinese journalist he was certain they would not understand. “On one hand, they cannot understand poetry,” Xu said. “On the other I sometimes mention unpleasant experience, and I don’t want them to worry.”

The people around him believed a certain amount of suffering was normal, even necessary. Ask a veteran of Shenzhen’s factories about their early years, and, odds are, they will speak with pride about “eating bitterness,” a Chinese phrase that suggests an ability to endure. Born to parents who knew famine, earlier migrants moved from abject poverty on the farm to deadly sweatshops in the city. Those who survived have a tendency to see new arrivals as lacking resolve: a kids-these-days thing.

Xu Hongzhi and the editor who asked not to be named, had both, like millions before them, moved to the city as teenagers, toiled in tough conditions, and come out stronger. They believed Xu Lizhi would do the same if he just waited and worked. When he looked at Xu, the editor saw talent, not despair. “Things today are so much better than they used to be,” he says. “But I guess today’s generation has different needs and expectations.”

Xu alternated between hope and hopelessness. He dared to hope for respite from monotony and a chance to use his talent, and twice summoned the courage to apply, unsuccessfully, for desk jobs — as a librarian at the factory, and at his favorite Shenzhen bookstore Youyi. But when a local journalist asked him about his future, he said he could not expect too much: “We all hope our lives will become better and better, but most of us don’t control our destiny.”

Epilogue

As spring festival approached in 2014, Xu left his job at Foxconn without telling his family, his brother said. He told friends he was off to the city of Suzhou not far from Shanghai to see a girl and start afresh. It is unclear where he spent that spring and summer; he lost touch with several close friends, but paid his Shenzhen rent, his brother says.

In late September he re-emerged in Shenzhen and signed a new contract with Foxconn. Two days later, on the eve of China’s Oct. 1 National Day holiday, Xu Lizhi, by then 24, walked to a mall across from his favorite bookstore, took the elevator to the 17th floor, and jumped to his death. It was not until the news of another suicide broke that friends found his final poems and a post scheduled to publish on Oct.1: “A new day,” it read.

In the wake of his death, labor groups translated Xu’s work into English, leading to notices in Bloomberg News and the Washington Post. Chinese poet Qin Xiaoyu is making a documentary film about Xu’s life and work. He also published a slim volume of his poems. Foxconn, citing company policy, declined to answer specific questions about Xu.

Xu Hongzhi took the long-distance bus from Jieyang to negotiate a settlement with the company. Unable to take Xu Lizhi back to the village, he carried his brother’s ashes to the coast and scattered them in the sea. Zhou Qizao, a fellow worker-poet, penned a defiant tribute: “Another screw comes loose/ Another migrant worker brother jumps/ You die in place of me/ And I keep writing in place of you.”

— With reporting by Gu Yongqiang

If you or a loved one has suicidal thoughts, call 1-800-273-8255 or visit suicidepreventionlifeline.org.

Risks and challenges

Regardless of any outcome of this crowdfunding for our documentary Iron Moon, we are determined to screen it to the American public so that everyone gets a chance to watch this remarkable film. Due to very limited time, we need to prepay all the costs out of our own pockets before the crowdfunding campaign. Without your critical support and if the crowdfunding fails to achieve our goal, we have to take this financial burden, which will make it almost impossible for us to produce the next part of this trilogy.

NO. We are not in the process of completing any past project. The successful crowdfunding will actually make Iron Moon visible to Americans and help us start the second and third part of this making a trilogy dedicated to Chinese workers and their poems.

Learn about accountability on Kickstarter

FAQ

Have a question? If the info above doesn't help, you can ask the project creator directly.

Ask a question

Report this project to Kickstarter

For more information:

http://www.laborfest.net7

Added to the calendar on Mon, Oct 24, 2016 12:30PM

Add Your Comments

We are 100% volunteer and depend on your participation to sustain our efforts!

Get Involved

If you'd like to help with maintaining or developing the website, contact us.

Publish

Publish your stories and upcoming events on Indybay.

Topics

More

Search Indybay's Archives

Advanced Search

►

▼

IMC Network