From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

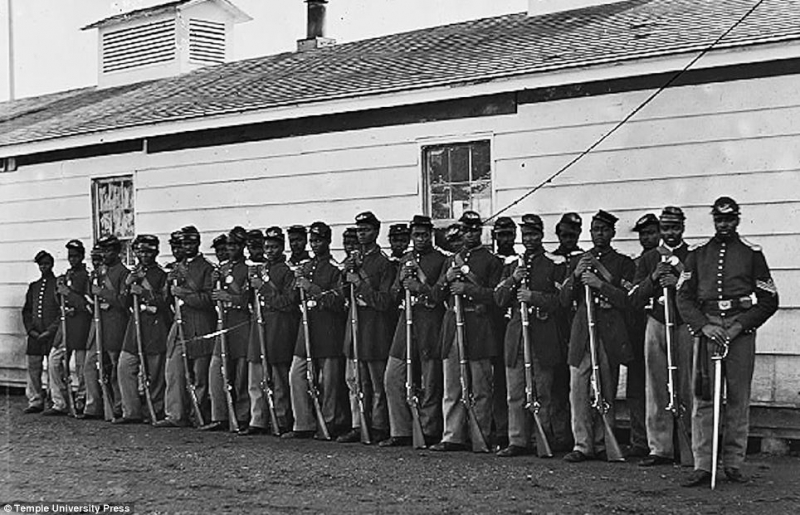

Freedom Summer of 1863 ~ US Colored Troops ~ Port Hudson, Louisiana

150th Anniversary of US Colored Troops officially fighting for a greater measure of freedom for people of African ancestry remains an open secret. Sadly the ongoing and escalating "Racism in our California Public School System" is best seen in the omission of the contributions of our service members of African ancestry to end "Slavery in California" and throughout the United States.

An extract from

Forged in Battle Proving Their Valor The Civil War Alliance of Black Soldiers and White Officers by Joseph T. Glatthaar

“The first major engagement in which black soldiers participated was an assault on Port Hudson, Louisiana, in late May 1863.

Control of the Mississippi River had long been a goal of the Union Army, and by the spring of 1863 it had secured the river’s entire course, except for Confederate bastions at Vicksburg, Mississippi and Port Hudson, Louisiana.

To cut off the Confederates in the Trans-Mississippi West and provide Midwestern farmers with a water route for the shipment of their crops, the War Department determined that a command under Maj. Gen. U. S. Grant was to capture Vicksburg, and Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks, head of the Department of the Gulf, was to seize Port Hudson.

For months the Confederates had been fortifying Port Hudson, particularly to the south and west, taking full advantage of the choppy terrain to erect an ominous defensive position. The occupation force consisted of some six thousand Confederates under the command of Maj. Gen. Franklin Garner, a gritty officer and talented engineer who hailed originally from New York.

In late May portions of Banks’s Nineteenth Corps converged on the area around Port Hudson, and after some intense fighting the Federals took a horseshoe-shaped position around the Port Hudson garrison, with flanks nestled near the river. Among Banks’s besiegers, filling in at the northern edge of the Union line and closest to the Mississippi river, were the 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guards, later the 73rd and 75th U. S. Colored infantry, a little over one thousand black soldiers in number.

The 3rd Louisiana Native Guards consisted of former slaves who had white officers. Originally, the regiment had black line officers, but efforts by Banks to purge the Louisiana native Guards of all black officers had already driven them from the service, regardless of qualifications or competence.

The 1st Louisiana Native Guards, though, were free {non-enslaved} blacks, with black captains and lieutenants who for the time being were unwilling to buckle under Banks’s pressure. According to its white colonel, the regiment had some of the best blood of Louisiana, the offspring of sundry white politicians, as well as numerous prominent and wealthy {non-enslaved} free blacks from New Orleans.

The next morning, when they assembled in position to begin their advance, no one in the Federal Army had examined the terrain. Several days earlier, as Banks’s forces approached Port Hudson from various directions, they had caught the Confederates by surprise. Gardner and his men had expected an attack from the south land possibly from the east, and they had devoted nearly all their time to fortifying their defenses in these areas. An advance in part from north of Port Hudson had caught them unprepared, and the Confederates had to throw up works hurriedly.

To their great advantage, though, the terrain suited their designs superbly. The black regiments were north of Foster’s Creek, and before they could do anything, they had to pass over a pontoon bridge to get at the Confederates. South of the creek, a thoroughfare called the Telegraph Road led to Port Hudson. The problems for the attackers were that a bluff ran parallel to the road on the Federals’ left, and the Confederates had positioned riflemen there to harass troops as they crossed the pontoons and attempted to move along the road. It was virtually impossible to get at these Confederates, because the area between the road land the bluff was choppy and filled with underbrush and fallen trees. To make matters worse, a Confederate engineer had skillfully tapped into the Mississippi River and drew backwater directly through that strip between the road and the bluff. On the right side of the road was a huge backwater swamp of willow, cotton-wood, and cypress trees. To the front of the advancing troops was a bluff, well defended by Confederate infantrymen and supported by artillery.

As if the Confederate defenders needed more help, the backwater cut across the pocket between that main Rebel line and the end of the bluff that ran alongside the road, shielding the Confederate artillery from possible assaults. Had an officer with authority and any sense examined the Confederate position, the charge of the 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guards would never have taken place.

The first assault came from troops to the east of the two black regiments, and once those blue columns failed to pierce the Confederate defense, the burden shifted to the blacks. Around 10:00 A. M. they began crossing the pontoon bridge over Foster’s Creek. Immediately a few Confederate sharpshooters peppered them with rifle fire as a warning for what was to come, but despite their losses, the black troops retained their composure. They quickly deployed as skirmishers and worked their way along the right side of the road, trying to use the timber as cover, although the swamp and felled trees delayed their advance and some Confederate artillery shells depleted their ranks.

The black regiments had hoped to rely on artillery and some white troops as support in their attack. All they got, though, were two artillery guns, which proved no help at all. After their crews hurled one round, Confederate artillery promptly silenced them with a barrage, and for the remainder of the fight they contributed nothing to the battle. Success in that sector, then, depended solely on the black troops.

Some six hundred yards from the main confederate works, amid the timber, the black regiment shifted to their left and formed two battle lines consisting of two rows each, with the 1st Louisiana native Guards in the lead. They emerged from the woods advancing rapidly, although once clear of the trees, fire from the Confederate riflemen on the bluff alongside the road now struck them in the flank and created gaps in the ranks.

As they reached a point some two hundred yards from the main works, the Confederates opened with a hail of canister, shell, and rifle fire that ripped through the lines of black troops. By dint of sheer determination, the men pressed onward to their slaughter.

When the sheets of Confederate lead staggered the first regiment, the 3rd Louisiana Native Guards joined the fray, yet their entry into the assault merely compounded the casualties. Because of the confusion on the battlefield, it is unclear how many times the two black regiments charged the Confederates.

The New Your Times eyewitness claimed that he saw six separate attacks, while both the Union and Confederate commanders on the scene counted only three. Nevertheless, the black troops demonstrated dash and courage in the face of overwhelming odds. Some soldiers attempted to wade through the backwater to get at the Confederates, and a handful of other tried to scale the bluff where the riflemen had posted themselves, to no avail.

In fact, never did the black troops seriously threaten to break through the Confederate lines, regardless of their grit. In defeat, these black troops demonstrated an inner strength comparable to that of any soldier in the Union Army.

After several charges, it had become apparent to everyone on the field that renewed attempts to take the Confederate position were insane, and eventually the troops fell back to the woods for good. Nearly two hundred black troops were casualties, some 20 percent of the two regiments, and to highlight the utter futility of the assault, they had inflicted no casualties upon the Confederates.

Despite the terrible defeat, the Battle of Port Hudson marked a turning point in attitudes toward the use of black soldiers. A lieutenant in the 3rd Louisiana Native Guards told a captain, My Co. was apparently brave. Yet they are mostly contrabands, and I must say I entertained some fears as to their pluck. But I have now none. And another officer noted, they fought with great desperation, and carried all before them. They had to be restrained for fear they would get too far in unsupported. They have shown that they can and will fight well.

From a more official viewpoint, Banks announced to Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, the severe test to which they were subjected, and the determined manner in which they encountered the enemy, leaves upon my mind no doubt of their ultimate success. In concurrence, Brig. Gen Daniel Ullmann, who was in the process of raising a black brigade in Louisiana, informed Secretary of War Stanton, the brilliant conduct of the colored regiments at Port Hudson, on the 27th has silenced cavilers and changed sneers into eulogizers.

There is no question but that they behaved with dauntless courage. The New York Times, which had cautiously endorsed the limited use of black troops on a trail basis just four months earlier, now declared the experiment a success.”

Extracted from Forged in Battle Proving Their Valor The Civil War Alliance of Black Soldiers and White Officers by Joseph T. Glatthaar, New York: The Free Press, 1990

Forged in Battle Proving Their Valor The Civil War Alliance of Black Soldiers and White Officers by Joseph T. Glatthaar

“The first major engagement in which black soldiers participated was an assault on Port Hudson, Louisiana, in late May 1863.

Control of the Mississippi River had long been a goal of the Union Army, and by the spring of 1863 it had secured the river’s entire course, except for Confederate bastions at Vicksburg, Mississippi and Port Hudson, Louisiana.

To cut off the Confederates in the Trans-Mississippi West and provide Midwestern farmers with a water route for the shipment of their crops, the War Department determined that a command under Maj. Gen. U. S. Grant was to capture Vicksburg, and Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks, head of the Department of the Gulf, was to seize Port Hudson.

For months the Confederates had been fortifying Port Hudson, particularly to the south and west, taking full advantage of the choppy terrain to erect an ominous defensive position. The occupation force consisted of some six thousand Confederates under the command of Maj. Gen. Franklin Garner, a gritty officer and talented engineer who hailed originally from New York.

In late May portions of Banks’s Nineteenth Corps converged on the area around Port Hudson, and after some intense fighting the Federals took a horseshoe-shaped position around the Port Hudson garrison, with flanks nestled near the river. Among Banks’s besiegers, filling in at the northern edge of the Union line and closest to the Mississippi river, were the 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guards, later the 73rd and 75th U. S. Colored infantry, a little over one thousand black soldiers in number.

The 3rd Louisiana Native Guards consisted of former slaves who had white officers. Originally, the regiment had black line officers, but efforts by Banks to purge the Louisiana native Guards of all black officers had already driven them from the service, regardless of qualifications or competence.

The 1st Louisiana Native Guards, though, were free {non-enslaved} blacks, with black captains and lieutenants who for the time being were unwilling to buckle under Banks’s pressure. According to its white colonel, the regiment had some of the best blood of Louisiana, the offspring of sundry white politicians, as well as numerous prominent and wealthy {non-enslaved} free blacks from New Orleans.

The next morning, when they assembled in position to begin their advance, no one in the Federal Army had examined the terrain. Several days earlier, as Banks’s forces approached Port Hudson from various directions, they had caught the Confederates by surprise. Gardner and his men had expected an attack from the south land possibly from the east, and they had devoted nearly all their time to fortifying their defenses in these areas. An advance in part from north of Port Hudson had caught them unprepared, and the Confederates had to throw up works hurriedly.

To their great advantage, though, the terrain suited their designs superbly. The black regiments were north of Foster’s Creek, and before they could do anything, they had to pass over a pontoon bridge to get at the Confederates. South of the creek, a thoroughfare called the Telegraph Road led to Port Hudson. The problems for the attackers were that a bluff ran parallel to the road on the Federals’ left, and the Confederates had positioned riflemen there to harass troops as they crossed the pontoons and attempted to move along the road. It was virtually impossible to get at these Confederates, because the area between the road land the bluff was choppy and filled with underbrush and fallen trees. To make matters worse, a Confederate engineer had skillfully tapped into the Mississippi River and drew backwater directly through that strip between the road and the bluff. On the right side of the road was a huge backwater swamp of willow, cotton-wood, and cypress trees. To the front of the advancing troops was a bluff, well defended by Confederate infantrymen and supported by artillery.

As if the Confederate defenders needed more help, the backwater cut across the pocket between that main Rebel line and the end of the bluff that ran alongside the road, shielding the Confederate artillery from possible assaults. Had an officer with authority and any sense examined the Confederate position, the charge of the 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guards would never have taken place.

The first assault came from troops to the east of the two black regiments, and once those blue columns failed to pierce the Confederate defense, the burden shifted to the blacks. Around 10:00 A. M. they began crossing the pontoon bridge over Foster’s Creek. Immediately a few Confederate sharpshooters peppered them with rifle fire as a warning for what was to come, but despite their losses, the black troops retained their composure. They quickly deployed as skirmishers and worked their way along the right side of the road, trying to use the timber as cover, although the swamp and felled trees delayed their advance and some Confederate artillery shells depleted their ranks.

The black regiments had hoped to rely on artillery and some white troops as support in their attack. All they got, though, were two artillery guns, which proved no help at all. After their crews hurled one round, Confederate artillery promptly silenced them with a barrage, and for the remainder of the fight they contributed nothing to the battle. Success in that sector, then, depended solely on the black troops.

Some six hundred yards from the main confederate works, amid the timber, the black regiment shifted to their left and formed two battle lines consisting of two rows each, with the 1st Louisiana native Guards in the lead. They emerged from the woods advancing rapidly, although once clear of the trees, fire from the Confederate riflemen on the bluff alongside the road now struck them in the flank and created gaps in the ranks.

As they reached a point some two hundred yards from the main works, the Confederates opened with a hail of canister, shell, and rifle fire that ripped through the lines of black troops. By dint of sheer determination, the men pressed onward to their slaughter.

When the sheets of Confederate lead staggered the first regiment, the 3rd Louisiana Native Guards joined the fray, yet their entry into the assault merely compounded the casualties. Because of the confusion on the battlefield, it is unclear how many times the two black regiments charged the Confederates.

The New Your Times eyewitness claimed that he saw six separate attacks, while both the Union and Confederate commanders on the scene counted only three. Nevertheless, the black troops demonstrated dash and courage in the face of overwhelming odds. Some soldiers attempted to wade through the backwater to get at the Confederates, and a handful of other tried to scale the bluff where the riflemen had posted themselves, to no avail.

In fact, never did the black troops seriously threaten to break through the Confederate lines, regardless of their grit. In defeat, these black troops demonstrated an inner strength comparable to that of any soldier in the Union Army.

After several charges, it had become apparent to everyone on the field that renewed attempts to take the Confederate position were insane, and eventually the troops fell back to the woods for good. Nearly two hundred black troops were casualties, some 20 percent of the two regiments, and to highlight the utter futility of the assault, they had inflicted no casualties upon the Confederates.

Despite the terrible defeat, the Battle of Port Hudson marked a turning point in attitudes toward the use of black soldiers. A lieutenant in the 3rd Louisiana Native Guards told a captain, My Co. was apparently brave. Yet they are mostly contrabands, and I must say I entertained some fears as to their pluck. But I have now none. And another officer noted, they fought with great desperation, and carried all before them. They had to be restrained for fear they would get too far in unsupported. They have shown that they can and will fight well.

From a more official viewpoint, Banks announced to Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, the severe test to which they were subjected, and the determined manner in which they encountered the enemy, leaves upon my mind no doubt of their ultimate success. In concurrence, Brig. Gen Daniel Ullmann, who was in the process of raising a black brigade in Louisiana, informed Secretary of War Stanton, the brilliant conduct of the colored regiments at Port Hudson, on the 27th has silenced cavilers and changed sneers into eulogizers.

There is no question but that they behaved with dauntless courage. The New York Times, which had cautiously endorsed the limited use of black troops on a trail basis just four months earlier, now declared the experiment a success.”

Extracted from Forged in Battle Proving Their Valor The Civil War Alliance of Black Soldiers and White Officers by Joseph T. Glatthaar, New York: The Free Press, 1990

Add Your Comments

We are 100% volunteer and depend on your participation to sustain our efforts!

Get Involved

If you'd like to help with maintaining or developing the website, contact us.

Publish

Publish your stories and upcoming events on Indybay.

Topics

More

Search Indybay's Archives

Advanced Search

►

▼

IMC Network