From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

PHILIPPINES: The ghosts of martial law

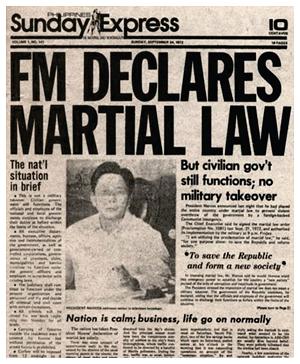

On September 21, forty years ago, President Ferdinand E. Marcos declared martial law. For almost 13-and-a-half years afterwards, the country suffered terribly from a brutal and corrupt dictatorship. Among the victims of the grave violations of human rights under martial law were the following: 3,257 “salvaged” (summarily executed), 35,000 tortured, and 70,000 incarcerated, as documented by historian Alfred McCoy.

Rated No. 2 in Transparency International’s (TI) list of the world’s most corrupt rulers, Marcos is believed to have plundered US$5 to $10 billion from the government’s coffers, the bulk of this during the martial law years. The massive, widespread and uncontrolled corruption under Marcos stunted the country’s economic growth severely.

After “people power” and the restoration of democracy in 1986, many Filipinos vowed that they would resist any attempt to bring back martial law or any other form of authoritarian rule. Never again!

With the passing of time, however, a lot of Filipinos have tended to forget those nightmare years. There have even been attempts to rewrite history, to paint the martial law era as halcyon times of discipline, beauty, development and prosperity.

The foremost advocates of such rewriting of martial law history are the Marcoses themselves – specifically, Imelda, Bongbong and Imee – who, most unfortunately, have managed to make a political comeback of sorts. No, they are not sorry at all for what Ferdinand Sr. did. In fact, they defend and justify his atrocious record.

The chief beneficiaries of Marcos’ ill-gotten wealth wallow in it, even flaunt it, and use this to try to expand their power. One made a failed bid for the presidency; another is now preparing for his own bid. They even have had the temerity to campaign for the ruthless and kleptocratic dictator to be given a hero’s burial.

The return of the Marcoses – perhaps the most visible and irritating reminder of the martial law years – is, however, not the most worrisome development. A deeper look at the legacy of Marcos’ martial law reveals that many of the evils of that era have actually stayed on or come back with a vengeance.

Patronage has been a longstanding feature of Philippine politics, but Marcos, after imposing martial law, succeeded in centralizing and systematically utilizing patronage as never before. Post-Marcos democracy has not provided enough safeguards to prevent presidents from using their control of patronage resources – especially pork barrel, the utmost symbol of Philippine patronage politics – for self-serving ends.

Former President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo distributed pork as largesse to her supporters. Fighting impeachment, she simply cut off pro-impeachment legislators from it.

Instead of abolishing pork, President Benigno Aquino III has more than tripled the funds for it. He has harnessed pork as an incentive for politicians to support his reforms, and made the pork process more transparent. But pork, by definition, is still patronage. And the enlarged pork poses a big risk: Aquino’s successors may decide to follow Arroyo’s example, not his.

Corruption and plunder

Presidents Joseph Estrada and Arroyo apparently followed in Marcos’ footsteps.

In just two-and-a-half years of being in power, Estrada amassed $78-$80 million, enough to put him as No. 10 in TI’s list of the most corrupt rulers. He was convicted of plunder, but pardoned shortly afterwards. Following a series of exposés of corruption scandals under Arroyo, some implicating her or members of her family, a Pulse Asia survey in late 2007 showed that Filipinos regarded her as the country’s most corrupt president, surpassing Estrada and even Marcos.

The possibility of plunder on a scale larger (in absolute terms) than that during Marcos’ time cannot be discounted as the Philippine economy has grown tremendously since then.

Rent-seeking clans, dynasties

Emerging in the early part of the American colonial period, political clans and dynasties became even more entrenched after the Philippines gained independence. Under martial law, political clans and dynasties that collaborated with Marcos became much more avaricious and brazen in exploiting government for private gain, especially through the pursuit and capture of “rents” – public subsidies, concessions, tax exemptions, monopolies, etc.

The 1987 Constitution bans political dynasties. Instead of passing a law to enable this constitutional ban, however, post-Marcos legislators have been much too busy building and expanding their own political dynasties. And local officials have followed suit. Under the Arroyo presidency, the rent-seeking was as avaricious and brazen as during martial law … or possibly even worse.

Crony capitalism

According to political scientist David Kang, Philippine money politics under martial law was characterized by “excessive top-down predation by Marcos and his cronies … and as a result the Philippines lost its opportunity to grow rapidly.”

In the post-Marcos era, the Philippines has in the main reverted to the usual patronage and rent-seeking by political clans and dynasties. But during the Estrada and Arroyo presidencies, crony capitalism became marked once again. Estrada guzzled drinks with his buddies in the infamous “Midnight Cabinet.” Before the NBN-ZTE exposé, former Director-General of the National Economic and Development Authority Romulo Neri had been quite forthcoming in lecturing about the “web of corruption” involving the “evil” Arroyo and the “oligarchs” close to Malacañang.

Warlords and private armies

Although warlords and their private armies already appeared after independence, they never enjoyed as much backing, latitude and impunity as they did under Marcos’ martial law, which political scientist John Sidel described as “a protracted period of national-level boss rule.”

Warlords and private armies are still very much around. By the Philippine National Police’s count, the country has 107 private armies. The power and privilege of warlords under Arroyo approached those under Marcos. This was horrendously demonstrated in the 2009 Maguindanao massacre, in which the private army of the warlord-governor Andal Ampatuan brutally killed 58 people.

President Aquino has ordered the dismantling of private armies, but whether this will actually be achieved remains to be seen.

Perversion of political institutions

By imposing authoritarian rule, Marcos destroyed the Philippines’ democratic institutions.

He did away with Congress, elections, political parties, etc., destroyed the independence and integrity of the judiciary and the constitutional commissions, and turned the military and police into his personal security forces.

When he “normalized” political processes in the late 1970s, the legislature, elections, political parties, etc., that he “restored” were perversions of real democratic institutions. Toward the end of Arroyo’s presidency, veteran journalist Amando Doronila noted that Arroyo had bequeathed “a legacy of ruined political institutions underpinning Philippine democracy.”

In destroying these institutions, Arroyo did not have to resort to martial law or authoritarian rule. Just “governance by patronage,” to borrow a phrase of sociologist Randy David.

Patrimonialistic political parties

Personality-based and indistinguishable from one another in ideology or program, the Philippines’ main political parties have served as convenient vehicles of patronage. Turncoatism, writes political scientist Felipe Miranda, is a venerable tradition.

Martial law saw the birth of a patrimonialistic political party, Kilusan ng Bagong Lipunan (KBL), which went beyond patronage, abetting and partaking in the dictator’s predation and deception. Post-martial law parties are worse than pre-martial law parties. As I have noted before, they can be set up, merged with others, split, resurrected, regurgitated, reconstituted, renamed, repackaged, recycled, or flushed down the toilet at anytime.

Especially under Arroyo, they have more and more behaved not so differently from Marcos’ KBL. Knowing where the pork is, politicians switch to the President’s party or coalition in droves.

Electoral fraud and violence

Under martial law, Marcos regularly rigged elections and referenda. The 1986 rigging proved to be his undoing.

Electoral fraud continues, sometimes worse than before. The Lanao del Sur warlord Ali Dimaporo once reportedly wired Marcos: “You are leading by 100,000 votes. Tell me if you need more.”

Under Arroyo, that was chicken feed. As “Hello, Garci” showed, Muslim Mindanao was turned into the national center for electoral fraud. In many areas of Maguindanao, Arroyo’s Dimaporo – Ampatuan – delivered results of 99% or more for her and 12-0 for her senatorial slate.

Election-related violence reached a historic peak – 905 deaths – in the 1971 elections, the prelude to martial law. After the “normalization” of political processes, election-related deaths exceeded 100 each time in the 1981, 1984 and 1986 polls. Election-related violence declined in the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s.

But deaths exceeded 100 once again in each of the midterm and presidential elections in 2001-2010. The Philippines now probably has the dubious distinction of having the most violent elections in the world.

Virtual land reform

Shortly after imposing martial law, Marcos declared the entire Philippines a land reform area and launched a land reform program that was touted to be the country’s most comprehensive ever, the response to the peasant masses’ long-ignored demand for social justice.

Due to intense landlord opposition, however, only 126,000 hectares out of the targeted 1,767,000 hectares of tenanted rice and corn land had been turned over to owner-cultivators by the time Marcos was driven out of power. Post-Marcos agrarian reform has fared not much better.

As quoted by Juan Mercado, economist Solita Monsod observed in 2008: “Landowners just wanted the program stopped. Over the last 20 years, they managed, through every means fair or foul, to keep over 80 percent of their land safe from redistribution.”

With the agrarian reform law due to expire in 2014, land reform seems to be more virtual than real.

Extra-judicial killings and disappearances

While efforts at compensation of martial law victims have continued, calls for the prosecution and punishment of human rights violators during the Marcos dictatorship have sadly died down.

The brutal repression that marked martial law is far from being a thing of the past. Under Arroyo, hundreds of members of left-wing activists were summarily killed or forcibly disappeared in the course of the government’s counterinsurgency campaign. In many cases, the government’s security or paramilitary forces were implicated.

By the end of Arroyo’s term, only 6 cases of extrajudicial killings were successfully prosecuted, with 11 defendants convicted. Human Rights Watch has criticized President Aquino for his unfulfilled promise to punish security forces responsible for human rights violations. Retired Army Maj Gen Jovito Palparan, who has been implicated in the abduction, torture and execution or disappearance of many leftist activists, remains scot-free despite a P1 million reward for his capture.

Separatism and communist insurgency

Although the Moro secessionist movement emerged in the late 1960s, it was during the first few months of martial law that the Moro rebellion broke out and quickly spread in various parts of Mindanao. Maoist guerrilla bands, which operated in a few areas before September 1972, grew into a nationwide insurgency under Marcos’ dictatorial rule.

Due in great part to the government’s lack of sustained commitment to achieving peace and development in Mindanao, the Moro rebellion has persisted in the post-Marcos era despite splits in the rebels’ ranks. The Philippines’ continuing oligarchic rule has played a major role in the persistence of the communist insurgency. The two rebellions are among the world’s most protracted and deadliest insurgencies, with the Moro rebellion claiming 120,000 lives and the Maoist insurgency, 45,000.

Advocates of “Never Again!” would do well to take Imelda, Bongbong and Imee to task more vigorously for defending a ruthless and corrupt dictator, for wallowing in his stolen wealth and for trying to distort martial law history. To counter the call for giving Marcos a hero’s burial, what could be put forward is the demand to give him a Bin Laden-style burial instead, which he fully deserves, and which would help dash all further attempts to transform a monster into a hero, savior or martyr.

Like the Marcoses, many other ghosts of martial law come and go, or have come back and stayed … or never left in the first place. Outside of their apparently “natural” habitat, they have adjusted, sometimes assumed new forms, and become as ghoulish, loathsome and destructive as before or worse.

The Philippine state has been under oligarchic rule from inception, that is, from the time the Philippines was granted independence. Oligarchic rule has persisted – in periods of “democracy” as well as authoritarianism. Not a few evils of authoritarianism in an oligarchic state can still live on, thrive or even worsen when authoritarianism gives way to a deficient democracy.

The Aquino government can be commended for its determined and relentless fight against corruption. But it can only go so far.

With Congress and local governments still very much dominated by landed, patronage-reared, rent-seeking political clans and dynasties, some with private armies, a reform-oriented president, even one who may resist the pressures of the oligarchic clan to which he belongs, can only do so much.

For the Philippines to get out of the rut of oligarchic rule, it may need not just a succession of reform-oriented public officials, but more importantly a vibrant and vigilant civil society that endeavors to learn, propagate, and take heed of, the lessons of history. - Rappler.com

(Nathan Gilbert Quimpo, an associate professor of political science and international relations at the University of Tsukuba in Japan, is the author of Contested Democracy and the Left in the Philippines after Marcos [2008] and co-author of Subversive Lives: A Family Memoir of the Marcos Years [2012]. A longtime political activist, Quimpo was a political prisoner under the Marcos dictatorship.)

After “people power” and the restoration of democracy in 1986, many Filipinos vowed that they would resist any attempt to bring back martial law or any other form of authoritarian rule. Never again!

With the passing of time, however, a lot of Filipinos have tended to forget those nightmare years. There have even been attempts to rewrite history, to paint the martial law era as halcyon times of discipline, beauty, development and prosperity.

The foremost advocates of such rewriting of martial law history are the Marcoses themselves – specifically, Imelda, Bongbong and Imee – who, most unfortunately, have managed to make a political comeback of sorts. No, they are not sorry at all for what Ferdinand Sr. did. In fact, they defend and justify his atrocious record.

The chief beneficiaries of Marcos’ ill-gotten wealth wallow in it, even flaunt it, and use this to try to expand their power. One made a failed bid for the presidency; another is now preparing for his own bid. They even have had the temerity to campaign for the ruthless and kleptocratic dictator to be given a hero’s burial.

The return of the Marcoses – perhaps the most visible and irritating reminder of the martial law years – is, however, not the most worrisome development. A deeper look at the legacy of Marcos’ martial law reveals that many of the evils of that era have actually stayed on or come back with a vengeance.

Patronage has been a longstanding feature of Philippine politics, but Marcos, after imposing martial law, succeeded in centralizing and systematically utilizing patronage as never before. Post-Marcos democracy has not provided enough safeguards to prevent presidents from using their control of patronage resources – especially pork barrel, the utmost symbol of Philippine patronage politics – for self-serving ends.

Former President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo distributed pork as largesse to her supporters. Fighting impeachment, she simply cut off pro-impeachment legislators from it.

Instead of abolishing pork, President Benigno Aquino III has more than tripled the funds for it. He has harnessed pork as an incentive for politicians to support his reforms, and made the pork process more transparent. But pork, by definition, is still patronage. And the enlarged pork poses a big risk: Aquino’s successors may decide to follow Arroyo’s example, not his.

Corruption and plunder

Presidents Joseph Estrada and Arroyo apparently followed in Marcos’ footsteps.

In just two-and-a-half years of being in power, Estrada amassed $78-$80 million, enough to put him as No. 10 in TI’s list of the most corrupt rulers. He was convicted of plunder, but pardoned shortly afterwards. Following a series of exposés of corruption scandals under Arroyo, some implicating her or members of her family, a Pulse Asia survey in late 2007 showed that Filipinos regarded her as the country’s most corrupt president, surpassing Estrada and even Marcos.

The possibility of plunder on a scale larger (in absolute terms) than that during Marcos’ time cannot be discounted as the Philippine economy has grown tremendously since then.

Rent-seeking clans, dynasties

Emerging in the early part of the American colonial period, political clans and dynasties became even more entrenched after the Philippines gained independence. Under martial law, political clans and dynasties that collaborated with Marcos became much more avaricious and brazen in exploiting government for private gain, especially through the pursuit and capture of “rents” – public subsidies, concessions, tax exemptions, monopolies, etc.

The 1987 Constitution bans political dynasties. Instead of passing a law to enable this constitutional ban, however, post-Marcos legislators have been much too busy building and expanding their own political dynasties. And local officials have followed suit. Under the Arroyo presidency, the rent-seeking was as avaricious and brazen as during martial law … or possibly even worse.

Crony capitalism

According to political scientist David Kang, Philippine money politics under martial law was characterized by “excessive top-down predation by Marcos and his cronies … and as a result the Philippines lost its opportunity to grow rapidly.”

In the post-Marcos era, the Philippines has in the main reverted to the usual patronage and rent-seeking by political clans and dynasties. But during the Estrada and Arroyo presidencies, crony capitalism became marked once again. Estrada guzzled drinks with his buddies in the infamous “Midnight Cabinet.” Before the NBN-ZTE exposé, former Director-General of the National Economic and Development Authority Romulo Neri had been quite forthcoming in lecturing about the “web of corruption” involving the “evil” Arroyo and the “oligarchs” close to Malacañang.

Warlords and private armies

Although warlords and their private armies already appeared after independence, they never enjoyed as much backing, latitude and impunity as they did under Marcos’ martial law, which political scientist John Sidel described as “a protracted period of national-level boss rule.”

Warlords and private armies are still very much around. By the Philippine National Police’s count, the country has 107 private armies. The power and privilege of warlords under Arroyo approached those under Marcos. This was horrendously demonstrated in the 2009 Maguindanao massacre, in which the private army of the warlord-governor Andal Ampatuan brutally killed 58 people.

President Aquino has ordered the dismantling of private armies, but whether this will actually be achieved remains to be seen.

Perversion of political institutions

By imposing authoritarian rule, Marcos destroyed the Philippines’ democratic institutions.

He did away with Congress, elections, political parties, etc., destroyed the independence and integrity of the judiciary and the constitutional commissions, and turned the military and police into his personal security forces.

When he “normalized” political processes in the late 1970s, the legislature, elections, political parties, etc., that he “restored” were perversions of real democratic institutions. Toward the end of Arroyo’s presidency, veteran journalist Amando Doronila noted that Arroyo had bequeathed “a legacy of ruined political institutions underpinning Philippine democracy.”

In destroying these institutions, Arroyo did not have to resort to martial law or authoritarian rule. Just “governance by patronage,” to borrow a phrase of sociologist Randy David.

Patrimonialistic political parties

Personality-based and indistinguishable from one another in ideology or program, the Philippines’ main political parties have served as convenient vehicles of patronage. Turncoatism, writes political scientist Felipe Miranda, is a venerable tradition.

Martial law saw the birth of a patrimonialistic political party, Kilusan ng Bagong Lipunan (KBL), which went beyond patronage, abetting and partaking in the dictator’s predation and deception. Post-martial law parties are worse than pre-martial law parties. As I have noted before, they can be set up, merged with others, split, resurrected, regurgitated, reconstituted, renamed, repackaged, recycled, or flushed down the toilet at anytime.

Especially under Arroyo, they have more and more behaved not so differently from Marcos’ KBL. Knowing where the pork is, politicians switch to the President’s party or coalition in droves.

Electoral fraud and violence

Under martial law, Marcos regularly rigged elections and referenda. The 1986 rigging proved to be his undoing.

Electoral fraud continues, sometimes worse than before. The Lanao del Sur warlord Ali Dimaporo once reportedly wired Marcos: “You are leading by 100,000 votes. Tell me if you need more.”

Under Arroyo, that was chicken feed. As “Hello, Garci” showed, Muslim Mindanao was turned into the national center for electoral fraud. In many areas of Maguindanao, Arroyo’s Dimaporo – Ampatuan – delivered results of 99% or more for her and 12-0 for her senatorial slate.

Election-related violence reached a historic peak – 905 deaths – in the 1971 elections, the prelude to martial law. After the “normalization” of political processes, election-related deaths exceeded 100 each time in the 1981, 1984 and 1986 polls. Election-related violence declined in the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s.

But deaths exceeded 100 once again in each of the midterm and presidential elections in 2001-2010. The Philippines now probably has the dubious distinction of having the most violent elections in the world.

Virtual land reform

Shortly after imposing martial law, Marcos declared the entire Philippines a land reform area and launched a land reform program that was touted to be the country’s most comprehensive ever, the response to the peasant masses’ long-ignored demand for social justice.

Due to intense landlord opposition, however, only 126,000 hectares out of the targeted 1,767,000 hectares of tenanted rice and corn land had been turned over to owner-cultivators by the time Marcos was driven out of power. Post-Marcos agrarian reform has fared not much better.

As quoted by Juan Mercado, economist Solita Monsod observed in 2008: “Landowners just wanted the program stopped. Over the last 20 years, they managed, through every means fair or foul, to keep over 80 percent of their land safe from redistribution.”

With the agrarian reform law due to expire in 2014, land reform seems to be more virtual than real.

Extra-judicial killings and disappearances

While efforts at compensation of martial law victims have continued, calls for the prosecution and punishment of human rights violators during the Marcos dictatorship have sadly died down.

The brutal repression that marked martial law is far from being a thing of the past. Under Arroyo, hundreds of members of left-wing activists were summarily killed or forcibly disappeared in the course of the government’s counterinsurgency campaign. In many cases, the government’s security or paramilitary forces were implicated.

By the end of Arroyo’s term, only 6 cases of extrajudicial killings were successfully prosecuted, with 11 defendants convicted. Human Rights Watch has criticized President Aquino for his unfulfilled promise to punish security forces responsible for human rights violations. Retired Army Maj Gen Jovito Palparan, who has been implicated in the abduction, torture and execution or disappearance of many leftist activists, remains scot-free despite a P1 million reward for his capture.

Separatism and communist insurgency

Although the Moro secessionist movement emerged in the late 1960s, it was during the first few months of martial law that the Moro rebellion broke out and quickly spread in various parts of Mindanao. Maoist guerrilla bands, which operated in a few areas before September 1972, grew into a nationwide insurgency under Marcos’ dictatorial rule.

Due in great part to the government’s lack of sustained commitment to achieving peace and development in Mindanao, the Moro rebellion has persisted in the post-Marcos era despite splits in the rebels’ ranks. The Philippines’ continuing oligarchic rule has played a major role in the persistence of the communist insurgency. The two rebellions are among the world’s most protracted and deadliest insurgencies, with the Moro rebellion claiming 120,000 lives and the Maoist insurgency, 45,000.

Advocates of “Never Again!” would do well to take Imelda, Bongbong and Imee to task more vigorously for defending a ruthless and corrupt dictator, for wallowing in his stolen wealth and for trying to distort martial law history. To counter the call for giving Marcos a hero’s burial, what could be put forward is the demand to give him a Bin Laden-style burial instead, which he fully deserves, and which would help dash all further attempts to transform a monster into a hero, savior or martyr.

Like the Marcoses, many other ghosts of martial law come and go, or have come back and stayed … or never left in the first place. Outside of their apparently “natural” habitat, they have adjusted, sometimes assumed new forms, and become as ghoulish, loathsome and destructive as before or worse.

The Philippine state has been under oligarchic rule from inception, that is, from the time the Philippines was granted independence. Oligarchic rule has persisted – in periods of “democracy” as well as authoritarianism. Not a few evils of authoritarianism in an oligarchic state can still live on, thrive or even worsen when authoritarianism gives way to a deficient democracy.

The Aquino government can be commended for its determined and relentless fight against corruption. But it can only go so far.

With Congress and local governments still very much dominated by landed, patronage-reared, rent-seeking political clans and dynasties, some with private armies, a reform-oriented president, even one who may resist the pressures of the oligarchic clan to which he belongs, can only do so much.

For the Philippines to get out of the rut of oligarchic rule, it may need not just a succession of reform-oriented public officials, but more importantly a vibrant and vigilant civil society that endeavors to learn, propagate, and take heed of, the lessons of history. - Rappler.com

(Nathan Gilbert Quimpo, an associate professor of political science and international relations at the University of Tsukuba in Japan, is the author of Contested Democracy and the Left in the Philippines after Marcos [2008] and co-author of Subversive Lives: A Family Memoir of the Marcos Years [2012]. A longtime political activist, Quimpo was a political prisoner under the Marcos dictatorship.)

Add Your Comments

We are 100% volunteer and depend on your participation to sustain our efforts!

Get Involved

If you'd like to help with maintaining or developing the website, contact us.

Publish

Publish your stories and upcoming events on Indybay.

Topics

More

Search Indybay's Archives

Advanced Search

►

▼

IMC Network