From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

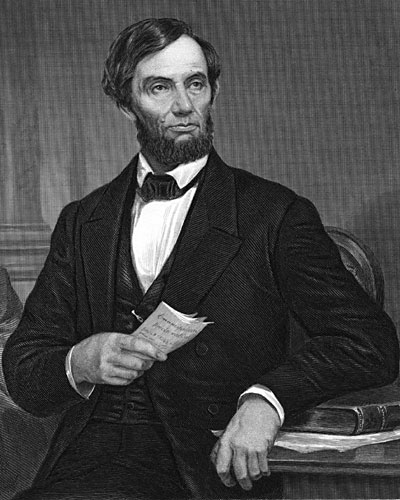

Emancipation Proclamation ~ "We must free the slaves or be ourselves subdueded"

Lincoln: The Constitution and the Civil War exhibit is open at the William Jessup University Paul Nystrom Library during regular hours. On Sunday, September 9, 2012 ~ California Admission Day, regional interfaith based organizations are planning to view the exhibit scheduled to to be available 3:00 p.m. ~ Midnight. Paul Finkelman's article helps to build a strong conversation toward healthy dialogue and education.

On July 12, 1862, Abraham Lincoln met privately in the White House, for the second time, with most of the senators and congressmen from the loyal slave states – Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky and Missouri.

It wasn’t the most relaxed of meetings: most of these delegates were Democrats; some grudgingly supported the war effort, while others were more enthusiastic about the Union cause, as long as the conflict was solely for the purpose of restoring the Union.

Many of them were slave owners, and virtually all supported slavery — like the Confederates, they believed that the proper status of blacks was as slaves, or, where circumstances warranted, as free people with limited rights. Most agreed with Chief Justice Roger B. Taney’s conclusion in the 1857 case Dred Scott v. Sandford that blacks could never be citizens of the United States.

Except for the handful of Republicans in the gathering, the delegation undoubtedly hoped to see Lincoln defeated in the 1864 election.

But more uncomfortable than the makeup of the meeting was its message: Lincoln asked these border-state politicians to return to their home states and lobby for abolition. Congress was willing to offer compensated emancipation if any of the loyal slave states would begin to end bondage, so the president needed one or more of them to take the initiative.

Lincoln’s strategy was to argue that the loyal slave states would help the war effort by showing the rebels “that, in no event, will the states you represent ever join their proposed Confederacy.” While Lincoln did not expect the border states to secede and join the Confederacy, he argued that voluntary emancipation in those states would be a blow to Confederate hopes and morale. If the upper South ended slavery, even the most optimistic Confederates would know that the four loyal slave states would not be leaving the Union.

This proposal dovetailed with Lincoln’s personal hatred of slavery and his “oft-expressed personal wish that all men everywhere could be free.” It also would increase his stature with the antislavery wing for the Republican Party, which was clamoring for some direct attack on slavery.

Lincoln’s position was also a practical one. One way or the other, he said, slavery was done for — he famously told them that “incidents of war” could “not be avoided” and that “mere friction and abrasion” would destroy slavery.

He bluntly predicted that the institution “will be gone and you will have nothing valuable in lieu of it.” He also pointed out that Gen. David Hunter had just issued a proclamation in Union-held coastal South Carolina to end slavery there. Lincoln had countermanded that proclamation (he saw it as a usurpation of the president’s role), but he also noted that Hunter’s proclamation had been very popular, and that he personally considered Hunter an “honest man” and “my friend.” The message was clear: slavery would soon end, and the border state representatives should take what they could get for themselves and their constituents.

But the gathered representatives and senators did not take the hint, probably still believing, as pro-slavery forces had argued before the war, that any move against slavery would be unconstitutional. Indeed, two days later more than two-thirds of them – 20 in all – signed a letter saying precisely that (eight border state representatives then published letters of their own, supporting the president).

On July 14, the same day that the border state representatives denounced emancipation, Lincoln made one final stab at gradualism with a bill to compensate states that ended slavery. The bill left blank the amount that Congress would appropriate for each slave, but it provided that the money would come in the form of federal bonds given to the states.

The bill was part of Lincoln’s strategy to end slavery at the state level where possible, as a way of setting up the possibility of ending it on the national level. If he could get Kentucky or Maryland to end slavery, he felt, it would be easier to end it in the South. Such an approach was also consistent with prewar notions of constitutionalism — that the states had sole authority over issues of property. The bill went through two readings, but Congress adjourned before acting on it.

Lincoln surely knew that this bill, like his meeting with the border state representatives, would go nowhere. Nevertheless, this very public attempt was valuable. As in his response to Hunter, Lincoln was demonstrating to the nation that he was not acting precipitously or incautiously. On the contrary, he was doing everything he could, at least publicly, to end slavery with the least amount of turmoil and social dislocation.

The proposed bill must also be seen in the context of Lincoln’s actions on July 13, the day before he introduced the bill and the day after his meeting with the border state representatives. That day he privately told Secretary of State William H. Seward and Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles that he was going to issue a proclamation declaring emancipation for all slaves in the Confederacy.

This was not a sudden response to the border state representatives’ rejection of compensated emancipation: even had they accepted Lincoln’s proposal, it would not have affected slavery in the Confederacy, where most slaves lived. Indeed, Lincoln told Welles that for weeks the issue had “occupied his mind and thoughts day and night.”

Lincoln told Welles the issue was one of military necessity. “We must free the slaves” he said, “or be ourselves subdued.”

Slaves, Lincoln argued “were undeniably an element of strength to those who had their service, and we must decide whether that element should be with us or against us.”

Lincoln also rejected the idea that the Constitution still protected slavery in the Confederacy. The rebels,” he said, “could not at the same time throw off the Constitution and invoke its aid. Having made war on the Government, they were subject to the incidents and calamities of war.”

Lincoln had found a constitutional theory that would be acceptable to most Northerners. Regardless of how they felt about slavery or the constitutional power of the federal government, few were willing to come to the defense of the rebels.

And in any case, the legal questions were largely moot: until the war ended with a Union victory, the South couldn’t very easily challenge the proclamation in court. After decades of political and constitutional stalemate over slavery, Lincoln had figured out a path toward freedom for millions of men and women in bondage.

It wasn’t the most relaxed of meetings: most of these delegates were Democrats; some grudgingly supported the war effort, while others were more enthusiastic about the Union cause, as long as the conflict was solely for the purpose of restoring the Union.

Many of them were slave owners, and virtually all supported slavery — like the Confederates, they believed that the proper status of blacks was as slaves, or, where circumstances warranted, as free people with limited rights. Most agreed with Chief Justice Roger B. Taney’s conclusion in the 1857 case Dred Scott v. Sandford that blacks could never be citizens of the United States.

Except for the handful of Republicans in the gathering, the delegation undoubtedly hoped to see Lincoln defeated in the 1864 election.

But more uncomfortable than the makeup of the meeting was its message: Lincoln asked these border-state politicians to return to their home states and lobby for abolition. Congress was willing to offer compensated emancipation if any of the loyal slave states would begin to end bondage, so the president needed one or more of them to take the initiative.

Lincoln’s strategy was to argue that the loyal slave states would help the war effort by showing the rebels “that, in no event, will the states you represent ever join their proposed Confederacy.” While Lincoln did not expect the border states to secede and join the Confederacy, he argued that voluntary emancipation in those states would be a blow to Confederate hopes and morale. If the upper South ended slavery, even the most optimistic Confederates would know that the four loyal slave states would not be leaving the Union.

This proposal dovetailed with Lincoln’s personal hatred of slavery and his “oft-expressed personal wish that all men everywhere could be free.” It also would increase his stature with the antislavery wing for the Republican Party, which was clamoring for some direct attack on slavery.

Lincoln’s position was also a practical one. One way or the other, he said, slavery was done for — he famously told them that “incidents of war” could “not be avoided” and that “mere friction and abrasion” would destroy slavery.

He bluntly predicted that the institution “will be gone and you will have nothing valuable in lieu of it.” He also pointed out that Gen. David Hunter had just issued a proclamation in Union-held coastal South Carolina to end slavery there. Lincoln had countermanded that proclamation (he saw it as a usurpation of the president’s role), but he also noted that Hunter’s proclamation had been very popular, and that he personally considered Hunter an “honest man” and “my friend.” The message was clear: slavery would soon end, and the border state representatives should take what they could get for themselves and their constituents.

But the gathered representatives and senators did not take the hint, probably still believing, as pro-slavery forces had argued before the war, that any move against slavery would be unconstitutional. Indeed, two days later more than two-thirds of them – 20 in all – signed a letter saying precisely that (eight border state representatives then published letters of their own, supporting the president).

On July 14, the same day that the border state representatives denounced emancipation, Lincoln made one final stab at gradualism with a bill to compensate states that ended slavery. The bill left blank the amount that Congress would appropriate for each slave, but it provided that the money would come in the form of federal bonds given to the states.

The bill was part of Lincoln’s strategy to end slavery at the state level where possible, as a way of setting up the possibility of ending it on the national level. If he could get Kentucky or Maryland to end slavery, he felt, it would be easier to end it in the South. Such an approach was also consistent with prewar notions of constitutionalism — that the states had sole authority over issues of property. The bill went through two readings, but Congress adjourned before acting on it.

Lincoln surely knew that this bill, like his meeting with the border state representatives, would go nowhere. Nevertheless, this very public attempt was valuable. As in his response to Hunter, Lincoln was demonstrating to the nation that he was not acting precipitously or incautiously. On the contrary, he was doing everything he could, at least publicly, to end slavery with the least amount of turmoil and social dislocation.

The proposed bill must also be seen in the context of Lincoln’s actions on July 13, the day before he introduced the bill and the day after his meeting with the border state representatives. That day he privately told Secretary of State William H. Seward and Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles that he was going to issue a proclamation declaring emancipation for all slaves in the Confederacy.

This was not a sudden response to the border state representatives’ rejection of compensated emancipation: even had they accepted Lincoln’s proposal, it would not have affected slavery in the Confederacy, where most slaves lived. Indeed, Lincoln told Welles that for weeks the issue had “occupied his mind and thoughts day and night.”

Lincoln told Welles the issue was one of military necessity. “We must free the slaves” he said, “or be ourselves subdued.”

Slaves, Lincoln argued “were undeniably an element of strength to those who had their service, and we must decide whether that element should be with us or against us.”

Lincoln also rejected the idea that the Constitution still protected slavery in the Confederacy. The rebels,” he said, “could not at the same time throw off the Constitution and invoke its aid. Having made war on the Government, they were subject to the incidents and calamities of war.”

Lincoln had found a constitutional theory that would be acceptable to most Northerners. Regardless of how they felt about slavery or the constitutional power of the federal government, few were willing to come to the defense of the rebels.

And in any case, the legal questions were largely moot: until the war ended with a Union victory, the South couldn’t very easily challenge the proclamation in court. After decades of political and constitutional stalemate over slavery, Lincoln had figured out a path toward freedom for millions of men and women in bondage.

For more information:

http://www.jessup.edu/library/about/hours

We are 100% volunteer and depend on your participation to sustain our efforts!

Get Involved

If you'd like to help with maintaining or developing the website, contact us.

Publish

Publish your stories and upcoming events on Indybay.

Topics

More

Search Indybay's Archives

Advanced Search

►

▼

IMC Network