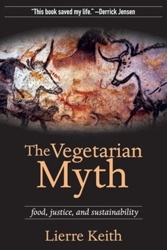

Lierre Keith's Elaborate, Self-Congratulatory Excuse for Abandoning Veganism at BT Books

Where she runs off the rails is with just about everything else in the book -- when she confuses her own psychology with that of every vegan or vegetarian (veg*n), when she commits numerous logical errors in support of her anti-vegan position, and when she inaccurately attempts to discredit facts about the destructiveness of today's American meat-centric diet based on small samples of data from a handful of existing niche farms that she unscientifically extrapolates to a distant hypothetical future.

When one considers that the vast majority of agriculture in the U.S. today is centered around meat and dairy production -- that the majority of vegetable matter raised in this country is grown to support livestock so that we can have plentiful meat -- one might wonder why Lierre Keith, in her quest to reduce the ecological harm of modern agriculture, decided to come after the veg*ns first, especially as they represent likely less than 5% of the population. And therein lies the answer to many of the book's flaws. Keith comes at veg*ns so directly because she claims that she was once a 20-year vegan herself before she found her new religion. Apparently, she was unable to maintain her health during that time by following an informed and complete vegan diet. So in attacking veg*ns, she is distancing herself from her former self. She is rationalizing and excusing her decision to consume the flesh of animals again. That is the essence of why she has written the book and she admits as much in its intro, although not in those exact words.

It is this process of self-justification for her decision to begin consuming meat again, and one assumes dairy as well, that has brought forth "The Vegetarian Myth". It comes off as an attempt to reverse engineer a rationale after she lost her personal faith in veg*nism, partly due to her inability to maintain her health by eating properly. Consider that she began to consume meat again and then released the book several years later. She projects that attempt to resolve her cognitive dissonance onto every veg*n alive today.

If she really wanted to come after modern agriculture, Keith could have left the attack on veg*ns out of it, or at least not made their role in modern agriculture the central premise of the book. Veg*ns tend to be some of the most conscientious people regarding their consumption, leaving a much smaller footprint than most Americans because veg*ns consume their nutrients directly rather than inefficiently through a food animal. It is well documented, and common sense, that it takes many times more resources to grow animals for food than it does to grow produce for food. Basic formulations about the inherent inefficiencies in a meat-based diet do not even take into account the massive amounts of pollution produced by food animals. Dairy cows in California alone produce more waste than all of the state's residents every year, and that does not include the millions of other food animals raised in the state. Hog farm waste lagoons are increasingly a noxious issue in many communities. And while you don't hear Al Gore say it, livestock is one of the greatest contributors to global warming due to the massive amounts of methane released by the animals. As simply as it can be stated, stopping eating meat (and dairy) today is one of the most important things individuals can do to substantially reduce their role in harming the environment. There are other positive steps individuals can take related to their food choices but few, if any, are as immediate and significant.

Lierre Keith presumably knows all of this, yet none of it matters to her any longer. She's found a way around the difficult truth of meat production today in America, where 95% of food animals are raised in factory farms. She dismisses the hard facts about the environmental destruction currently being done in the name of animal agriculture because she can point to a handful of small farms where the animals are allowed to graze. She completely ignores that these farms are an anachronism that not only offer very little for the majority of people today, but any widespread implementation of these farms is far off into the future at best and completely unrealistic at worst as the human population grows and the land and resources available for livestock decreases.

There is a danger to the public buying into Lierre Keith's personal psychodrama regarding her food (in)decisions. As she tells people through her book and at speaking engagements like the one at Bound Together Bookstore that eating meat is natural and good for the environment in some distant future, realistically people will continue (or begin again) to eat meat today, 95% of which comes from incredibly destructive factory farms, destructive to the environment, to human health, and to the animals who live miserable lives until their slaughter. Because the Inuit eat meat, or the Mayans did, we can all wear more leather and pretend that our meat-eating in America today is the same thing and somehow magically moves us to a pastoral future of happy, grazing livestock. She's allowed her personal eating dysfunction to color her world outlook to the point where she's obviously missing the forest for the trees. And she's advocating for others to follow her lead.

Unconvincingly, Lierre Keith wants us to believe that she has finally found her one true god, but with the obvious self-hate she betrays when she continually refers to veg*ns as ignorant or child-like, and with the faulty logical and factual ground on which she builds her case, it becomes apparent that the book is simply a therapeutic vehicle for her, not the self-congratulatory or evangelical effort it pretends to be. If she can convince us, then she can better assure herself that she is at peace with her decision to eat animals. Fortunately, a growing number of people are simply too intelligent and too well-informed to follow her gospel of psuedo-environmental meat-eating in the 21st century.

---------------------------------------------------

Credit must be given for the title of this critique to a comment by "c'mon irene". That an anonymous comment was used for the title of this post is intended to be ironic, as you will see below, in that Lierre Keith devotes an inordinate amount of paper and ink in her book to address something she supposedly read in an online message board.

If you doubt this critique of the book as a seriously flawed effort that PM Press should never have published, consider the following close examination of the first 14 pages of the book which Lierre Keith offers for free on her website. It is surprisingly sloppy and unprofessional for what one might expect from a PM Press title.

The original text appears in blue. Bolded text added for emphasis. Comments appear in black and/or brackets.

CHAPTER 1Why This Book?

This was not an easy book to write. For many of you, it won't be an easy book to read. I know. I was a vegan for almost twenty years. I know the reasons that compelled me to embrace an extreme diet and they are honorable, ennobling even. Reasons like justice, compassion, a desperate and all-encompassing longing to set the world right. To save the planet - the last trees bearing witness to ages, the scraps of wilderness still nurturing fading species, silent in their fur and feathers. To protect the vulnerable, the voiceless. To feed the hungry. At the very least to refrain from participating in the horror of factory farming.

These political passions are born of a hunger so deep that it touches on the spiritual. Or they were for me, and they still are. I want my life to be a battle cry, a war zone, an arrow pointed and loosed into the heart of domination: patriarchy, imperialism, industrialization, every system of power and sadism. If the martial imagery alienates you, I can rephrase it. I want my life - my body - to be a place where the earth is cherished, not devoured; where the sadist is granted no quarter; where the violence stops. And I want eating - the first nurturance - to be an act that sustains instead of kills.She's definitely into drama, as evidenced by these statements, as well as the title of the book in that she's totally flip-flopped and writes off 20 adult years of her life as having followed a myth. This intro is the first logical fallacy, an appeal to emotion (http://www.nizkor.org/features/fallacies/appeal-to-emotion.html).

This book is written to further those passions, that hunger. It is not an attempt to mock the concept of animal rights or to sneer at the people who want a gentler world. [But allow her to proceed to do exactly that after already calling veganism "extreme."] Instead, this book is an effort to honor our deepest longings for a just world. And those longings - for compassion, for sustainability, for an equitable distribution of resources - are not served by the philosophy or practice of vegetarianism. We have been led astray. The vegetarian Pied Pipers have the best of intentions. I'll state right now what I'll be repeating later: everything they say about factory farming is true. It is cruel, wasteful, and destructive. Nothing in this book is meant to excuse or promote the practices of industrial food production on any level.But that is exactly what the results of this book will be, if anyone follows her "Pied Piper" lead to meat-eating. A) People with the emotional and ethical vacillation of the author will believe her that vegetarianism is bad and meat-eating good and natural, B) Not having access to non-factory farmed meat and dairy, as most people don't in america, these same people will eat factory farmed meat, thinking it's natural while they con themselves into thinking that their actions today matter less than their "noble" desire for a magical form of agriculture for the masses in the future, and C) Increased rather than decreased environmental harm will happen as a result.

But the first mistake is in assuming that factory farming - a practice that is barely fifty years old - is the only way to raise animals. Their calculations on energy used, calories consumed, humans unfed, are all based on the notion that animals eat grain.This is a classic straw man (http://www.nizkor.org/features/fallacies/straw-man.html). Vegans I know don't think industrial confinement is the only way to raise animals. They are aware of the past and they know there is such a thing as "free range" and so forth today, but it's a niche today for the privileged and could never provide meat and dairy at the volumes factory farming does. factory farms exist for an economic reason. The amount of meat people eat has increased dramatically over the last hundred years, as has the number of people in existence. the author here seems to forget that the world's population has more than doubled from less than 3 billion in 1950 to more than 6 billion today, with reasonable projections of 9 billion people on the planet by 2050. Frankly, there's no going backwards to 1940s agriculture and still feeding a hungry world. It certainly can be done better and more sustainably, which should be the focus of her book rather than attacking vegetarians, but there's no going back.

Additionally, to her point about grain here, she is attempting to discredit or debunk calculations about how wasteful animal farming is today by comparing it with animal production 60 years or more ago, or on some mythical future. The calculations cited by advocates of veganism are accurate today for the vast majority of meat and dairy eaten by americans in 2009. Over 95% of animals raised for food today in america comes from factory farms. Those figures about the unnecessary waste and pollutions in meat-eating cannot honestly be debunked by some myth about all animals being raised for food in some free-roaming, pastural future.

You can feed grain to animals, but it is not the diet for which they were designed. Grain didn't exist until humans domesticated annual grasses, at most 12,000 years ago, while aurochs, the wild progenitors of the domestic cow, were around for two million years before that. For most of human history, browsers and grazers haven't been in competition with humans. They ate what we couldn't eat - cellulose - and turned it into what we could - protein and fat. Grain will dramatically increase the growth rate of beef cattle (there's a reason for the expression "cornfed") and the milk production of dairy cows. It will also kill them. The delicate bacterial balance of a cow's rumen will go acid and turn septic. Chickens get fatty liver disease if fed grain exclusively, and they don't need any grain to survive. Sheep and goats, also ruminants, should really never touch the stuff.This is historically accurate, but here we have a version of an appeal to tradition (http://www.nizkor.org/features/fallacies/appeal-to-tradition.html). Again, she neglects the growing world population of humans. Where will all these food animals actually roam? Kentucky Fried Chicken alone cranks through over 800,000,000 (yes, 800 million) chickens every year. And while she's waxing poetic about pre-agricultural humanity, domesticated animals for food are also a part of that agricultural "revolution". To truly go back (which can't actually be done with 9 billion people on the horizon), there would have to be no domesticated animals whatsoever. If so, where would these 9 billion people then get their meat? By hunting? How long until the entire earth is Easter Island and we have eaten every last wild creature roaming the planet?

This misunderstanding is born of ignorance, an ignorance that runs the length and breadth of the vegetarian myth [she seems rather disingenuous when she claimed earlier not to be interested in ridicule, but much of this is her ridiculing her past self and projecting her cognitive dissonance onto everyone who remains vegetarian, while ignoring that her entire book promotes a myth about the future while most vegans are concerned with what they can do today], through the nature of agriculture and ending in the nature of life. We are urban industrialists, and we don't know the origins of our food. This includes vegetarians, despite their claims to the truth. It included me, too, for twenty years. [Ah, yes, she is critical of herself as she flings shit at every last vegetarian.] Anyone who ate meat was in denial; only I had faced the facts. Certainly, most people who consume factory-farmed meat have never asked what died and how it died. But frankly, neither have most vegetarians.Ahem, most vegetarians are quite aware of how factory farmed animals die. If any are not knowledgable of every last detail of the origins of the produce they eat, well then the same could certainly be said for many if not most people in the US today, yet Lierre Keith chooses to attack vegetarians for it. Again, this is her own psychodrama bursting forth. She didn't know the origins of her food as a vegan, or even what exactly to eat to maintain her own health, and so she projects that onto all vegans and somehow forgets that the same applies to omnivores as well.

The truth is that agriculture is the most destructive thing humans have done to the planet, and more of the same won't save us. The truth is that agriculture requires the wholesale destruction of entire ecosystems. The truth is also that life isn't possible without death, that no matter what you eat, someone has to die to feed you.True enough, in a sense. Every taking from this world to sustain ourselves should be acknowledged as such, with the goal of not taking more than is sustainable. But just because something has to be taken does not justify all deaths, such as the unnecessary eating of animals. And this weak argument of hers also completely ignores the value in taking less, something that vegans do every day. While not exactly, this is almost a two-wrongs-make-a-right-fallacy (http://www.nizkor.org/features/fallacies/two-wrongs-make-a-right.html). Because there is any death involved with human eating, eating meat is fine she claims. While she should be advocating at least a reduction in the amount of meat people eat, she's instead attacking vegetarians and offering false hope that people can continue to eat meat like they do today and yet somehow all those billions of domesticated animals can just run around living happy lives.

I want a full accounting, an accounting that goes way beyond what's dead on your plate. I'm asking about everything that died in the process, everything that was killed to get that food onto your plate. That's the more radical question, and it's the only question that will produce the truth. How many rivers were dammed and drained, how many prairies plowed and forests pulled down, how much topsoil turned to dust and blown into ghosts? I want to know about all the species - not just the individuals, but the entire species - the chinook, the bison, the grasshopper sparrows, the grey wolves. And I want more than just the number of dead and gone. I want them back.Most vegans I know are are interested in more than just what is dead on a plate and are involved in many causes, including food issues like producing food locally and organics, to name just two. (But that's not to discount the horrible life that untold millions of animals suffer through long enough to be slaughtered for cheeseburgers or hotdogs or chicken wings.) This author, on the contrary, wants a single silver bullet to solve all ills. And worse, she's willing to cast aside the immediate good on the promise of some future perfect.

Despite what you've been told, and despite the earnestness of the tellers, eating soybeans isn't going to bring them back. [Wow, bigtime straw man and ridicule here.] Ninety-eight percent of the American prairie is gone, turned into a monocrop of annual grains [and strip malls and housing developments and so forth that are will not be available any time soon for cows to run around wild]. Plough cropping in Canada has destroyed 99 percent of the original humus. In fact, the disappearance of topsoil "rivals global warming as an environmental threat." When the rainforest falls to beef, progressives are outraged, aware, ready to boycott. But our attachment to the vegetarian myth leaves us uneasy, silent, and ultimately immobilized when the culprit is wheat and the victim is the prairie. We embraced as an article of faith that vegetarianism was the way to salvation, for us, for the planet. How could it be destroying either?Perhaps this is confessional on her part. She was looking for the magical silver bullet then, and look how wrong she was. She's found it now, she wants us to believe. Nevermind that most of the agricultural destruction in this country was and is done to grow crops for domesticated animals for food, hence the lack of water for salmon and the killing of predators like the grey wolves. It's the height of nutritional inefficiency to grow crops to feed animals to feed people, yet she neglects to admit this when she continues to disingenuously tie vegetarians to the environmental destruction.

We have to be willing to face the answer. What's looming in the shadows of our ignorance and denial [her ignorance and denial perhaps] is a critique of civilization itself. The starting point may be what we eat, but the end is an entire way of life, a global arrangement of power [some might call this utopia, which literally means "no place"], and no small measure of personal attachment to it. I remember the day in fourth grade when Miss Fox wrote two words on the blackboard: civilization and agriculture. I remember because of the hush in her voice, the gravitas of her words, the explanation that was almost oratory. This was Important. And I understood. Everything that was good in human culture flowed from this point: all ease, grace, justice. Religion, science, medicine, art were born, and the endless struggle against starvation, disease, violence could be won, all because humans figured out how to grow their own food.I'll merely point out here the misanthropy lurking in many of those words.

The reality is that agriculture has created a net loss for human rights and culture: slavery, imperialism, militarism, class divisions, chronic hunger, and disease. "The real problem, then, is not to explain why some people were slow to adopt agriculture but why anybody took it up at all, when it is so obviously beastly," writes Colin Tudge of The London School of Economics. Agriculture has also been devastating to the other creatures with whom we share the earth, and ultimately to the life support systems of the planet itself. What is at stake is everything. If we want a sustainable world, we have to be willing to examine the power relations behind the foundational myth of our culture. Anything less and we will fail.

Questioning at that level is difficult for most people. In this case, the emotional struggle inherent in resisting any hegemony is compounded by our dependence on civilization, and on our individual helplessness to stop it. Most of us would have no chance of survival if the industrial infrastructure collapsed tomorrow. And our consciousness is equally impeded by our powerlessness. There is no Ten Simple Things list in the last chapter because, frankly, there aren't ten simple things that will save the earth. There is no personal solution. There is an interlocking web of hierarchical arrangements, vast systems of power that have to be confronted and dismantled. We can disagree about how best to do that, but do it we must if the earth is to have any chance of surviving.So, in the meantime, keep eating meat, 95% of which comes from factory farms. Forget that most of that horrible agriculture is done to feed those animals. At least here, she recognizes that there is no silver bullet, although adopting a vegetarian diet is indeed one of the most immediate ways to decrease our participation in our agricultural overkill. It doesn't solve every last problem in the world, but it makes a big difference today in the issues this author seems to care about most.

In the end, all the fortitude in the world will be useless without enough information to chart a sustainable forward course, both personally and politically. One of my aims in writing this book is to provide that information. The vast majority of people in the US don't grow food, let alone hunt and gather it. [Thank goodness we don't hunt and gather it, or there'd be no wild animals left.] We have no way to judge how much death is embodied in a serving of salad, a bowl of fruit, a plate of beef. We live in urban environments, in the last whisper of forests, thousands of miles removed from the devastated rivers, prairies, wetlands, and the millions of creatures that died for our dinners. We don't even know what questions to ask to find out.We do know exactly many of these things. She is simply choosing to ignore what she knows about the gross inefficiencies in meat-eating. And while she may have been oblivious as a vegan, assuming she really was one, many vegans know a great deal about their food, even if it is impossible to know every last thing unless we are fortunate enough to buy everything we eat from local farmers and bakers.

In his book Long Life, Honey in the Heart, Martin Pretchel writes of the Mayan people and their concept of kas-limaal, which translates roughly as "mutual indebtedness, mutual insparkedness." "The knowledge that every animal, plant, person, wind, and season is indebted to the fruit of everything else is an adult knowledge. To get out of debt means you don't want to be part of life, and you don't want to grow into an adult," one of the elders explains to Pretchel.Yes, living in balance with nature is important. Eating meat today creates a huge and unnecessary ecological imbalance. But we are not Mayans nor will we ever be. And Lierre Keith -- again longing to idolize the past, in an ahistorical way -- seems to be forgetting that a central part of the "success" of mayan civilization was agriculture. They were not hunter-gatherers.

The only way out of the vegetarian myth is through the pursuit of kas-limaal, of adult knowledge. [Because vegans are children whereas those who eat meat are adults.] This is a concept we need, especially those of us who are impassioned by injustice. I know I needed it. In the narrative of my life, the first bite of meat after my twenty year hiatus marks the end of my youth, the moment when I assumed the responsibilities of adulthood [or the moment she willingly allowed herself to slip back into denial]. It was the moment I stopped fighting the basic algebra of embodiment: for someone to live, someone else has to die. In that acceptance, with all its suffering and sorrow, is the ability to choose a different way, a better way.Apparently, Keith also learned how to ignore the algebra regarding the enourmous resources wasted in a meat-based diet in America today.

The activist-farmers have a very different plan then the polemicist-writers to carry us from destruction to sustainability. The farmers are starting with completely different information. I've heard vegetarian activists claims that an acre of land can only support two chickens. [Straw man alert.] Joel Salatin, one of the High Priests of sustainable farming and someone who actually raises chickens, puts that figure at 250 an acre. [Nevermind the "high priest" worship or even quibbling about this figure. How many people will 250 chickens feed and for how long? Remember the population of the US is over 300,000,000 and growing.] Who do you believe? [Some random person I heard once or a high priest?] How many of us know enough to even have an opinion? Frances Moore Lappe says it takes twelve to sixteen pounds of grain to make one pound of beef. [And it is in that neighborhood today in the real world.] Meanwhile, Salatin raises cattle with no grain at all, rotating ruminants on perennial polycultures, building topsoil year by year. [Again, this is a niche for the privileged and not a serious plan to feed the masses any time soon, if the land even exists to let billions of food animals roam free.] Inhabitants of urban industrial cultures have no point of contact with grain, chickens, cows, or, for that matter, with topsoil. We have no basis of experience to outweigh the arguments of political vegetarians. We have no idea what plants, animals, or soil eat, or how much. Which means we have no idea what we ourselves are eating.Speak for yourself, please.

Confronting the truth about factory farming - its torturous treatment of animals, its environmental toll - was for me at age sixteen an act of profound importance. I knew the earth was dying. It was a daily emergency I had lived against forever. I was born in 1964. "Silent" and "spring" were inseparable: three syllables, not two words. Hell was here, in the oil refineries of northern New Jersey, the asphalt inferno of suburban sprawl, in the swelling tide of humans drowning the planet. I cried with Iron Eyes Cody, longed for his silent canoe and an unmolested continent of rivers and marshes, birds and fish. My brother and I would climb an ancient crabapple tree at the local park and dream about somehow buying a whole mountain. No people allowed, no discussion needed. Who would live there? Squirrels, was all I could come up with. Reader, don't laugh. Besides Bobby, our pet hamster, squirrels were the only animals I ever saw. My brother, well-socialized into masculinity, went on to torture insects and aim slingshots at sparrows. I became a vegan.This is cute at best, nonsensical nostalgia at its core.

Yes, I was an overly sensitive child. My favorite song at five - and here you are allowed to laugh - was Mary Hopkin's Those Were the Days. What romantic, tragic past could I possibly have mourned at age five? But it was so sad, so exquisite; I would listen to the song over and over until I was exhausted from weeping.

Okay, it's funny. But I can't laugh at the pain I felt over my powerless witnessing of the destruction of my planet. That was real and it overwhelmed me. And the political vegetarians offered a compelling salve. With no understanding of the nature of agriculture, the nature of nature, or ultimately the nature of life, I had no way to know that however honorable their impulses, their prescription was a dead end into the same destruction I burned to stop.On the contrary, vegans consume far less per person via agriculture than omnivores, so it is not the same. And, again, being vegan is not the be all and end all. There are a plenty of other food-related issues to fight for, but it is one major step in the right direction people can make today, while pining for a better agriculture is a long-term goal.

Those impulses and ignorances are inherent to the vegetarian myth. For two years after I returned to eating meat, I was compelled to read vegan message boards online. I don't know why. I wasn't looking for a fight. I never posted anything myself. Lots of small, intense subcultures have cult-like elements, and veganism is no exception. Maybe the compulsion had to do with my own confusion, spiritual, political, personal. Maybe I was revisiting the sight of an accident: this was where I had destroyed my body. Maybe I had questions and I wanted to see if I could hold my own against the answers that I had once held tight, answers that had felt righteous, but now felt empty. Maybe I don't know why. It left me anxious, angry, and desperate each time.Below is one of her major logical fallacies, an appeal to ridicule (http://www.nizkor.org/features/fallacies/appeal-to-ridicule.html). She uses something she found in some online forum as a major crux to her entire argument. Sorry, Lierre Keith, but there is such a thing as intelligent vegans, even if you were not one or you take the lazy road to pretend that this supposed online encounter represents all vegetarian thought. It also exposes her as a terrible writer as she uses this one example as a central "turning point" for her personally and in the narrative she is laying out in the book.

But one post marked a turning point. A vegan flushed out his idea to keep animals from being killed - not by humans, but by other animals. Someone should build a fence down the middle of the Serengeti, and divide the predators from the prey. Killing is wrong and no animals should ever have to die, so the big cats and wild canines would go on one side, while the wildebeests and zebras would live on the other. He knew the carnivores would be okay because they didn't need to be carnivores. That was a lie the meat industry told. He'd seen his dog eat grass: therefore, dogs could live on grass.Obviously, no sensible vegan advocates such a thing, nor can she find any vegan organization advocating for such a thing, but because she found this one dialogue online, she dedicates paragraph after paragraph to it in what is supposed to be a serious book. Who knows if this commenter was even who s/he said s/he was and not, for instance, a malicious pork industry profiteer and his/her buddies. I'll reserve comment for the most part now and allow Lierre Keith to continue unabated in beating down this wet noodle of an argument for the next 10 paragraphs or so.

No one objected. In fact, others chimed in. My cat eats grass, too, one woman added, all enthusiasm. So does mine! someone else posted. Everyone agreed that fencing was the solution to animal death.

Note well that the site for this liberatory project was Africa. No one mentioned the North American prairie, where carnivores and ruminants alike have been extirpated for the annual grains that vegetarians embrace. But I'll return to that in Chapter 3.

I knew enough to know that this was insane. But no one else on the message board could see anything wrong with the scheme. So, on the theory that many readers lack the knowledge to judge this plan, I'm going to walk you through this.

Carnivores cannot survive on cellulose. They may on occasion eat grass, but they use it medicinally, usually as a purgative to clear their digestive tracts of parasites. Ruminants, on the other hand, have evolved to eat grass. They have a rumen (hence, ruminant), the first in a series of multiple stomachs that acts as a fermentative vat. What's actually happening inside a cow or a zebra is that bacteria eat the grass, and the animals eat the bacteria.

Lions and hyenas and humans don't have a ruminant's digestive system. Literally from our teeth to our rectums we are designed for meat. We have no mechanism to digest cellulose.

So on the carnivore side of the fence, starvation will take every animal. Some will last longer than others, and those some will end their days as cannibals. The scavengers will have a Fat Tuesday party, but when the bones are picked clean, they'll starve as well. The graveyard won't end there. Without grazers to eat the grass, the land will eventually turn to desert.

Why? Because without grazers to literally level the playing field, the perennial plants mature, and shade out the basal growth point at the plant's base. In a brittle environment like the Serengeti, decay is mostly physical (weathering) and chemical (oxidative), not bacterial and biological as in a moist environment. In fact, the ruminants take over most of the biological functions of soil by digesting the cellulose and returning the nutrients, once again available, in the form of urine and feces.Note that she's going on and on in an attempt to scientifically refute an obviously silly proposal about fencing wild predators from wild prey.

But without ruminants, the plant matter will pile up, reducing growth, and begin killing the plants. The bare earth is now exposed to wind, sun, and rain, the minerals leech away, and the soil structure is destroyed. In our attempt to save animals, we've killed everything.

On the ruminant side of the fence, the wildebeests and friends will reproduce as effectively as ever. But without the check of predators, there will quickly be more grazers than grass. The animals will outstrip their food source, eat the plants down to the ground, and then starve to death, leaving behind a seriously degraded landscape.

The lesson here is obvious, though it is profound enough to inspire a religion: we need to be eaten as much as we need to eat. The grazers need their daily cellulose, but the grass also needs the animals. It needs the manure, with its nitrogen, minerals, and bacteria; it needs the mechanical check of grazing activity; and it needs the resources stored in animal bodies and freed up by degraders when animals die.Here, Lierre Keith so desperately wants to justify meat-eating that she seems to be saying that the earth and soil need domesticated animals to roam on them, again ahistorically forgetting that domesticated animals are a relatively recent phenomenon in the vast history of this living planet. Yes, wild creatures have done similar things, but there were far, far less of them than the total number of animals produced for meat today. To set the hundreds of billions of domesticated animals that americans are eating each year loose on the environment would certainly be no favor to a healthy ecology.

The grass and the grazers need each other as much as predators and prey. These are not one-way relationships, not arrangements of dominance and subordination. We aren't exploiting each other by eating. We are only taking turns.

That was my last visit to the vegan message boards. I realized then that people so deeply ignorant of the nature of life, with its mineral cycle and carbon trade, its balance points around an ancient circle of producers, consumers, and degraders, weren't going to be able to guide me or, indeed, make any useful decisions about sustainable human culture. By turning from adult knowledge, the knowledge that death is embedded in every creature's sustenance, from bacteria to grizzly bears, they would never be able to feed the emotional and spiritual hunger that ached in me from accepting that knowledge. Maybe in the end this book is an attempt to soothe that ache myself.If that's what the book is, perhaps she should have kept this amatuer effort to herself in a personal journal, or, at the very least, PM Press should have shown the discipline to pass on publishing it. Egads.

Get Involved

If you'd like to help with maintaining or developing the website, contact us.

Publish

Publish your stories and upcoming events on Indybay.