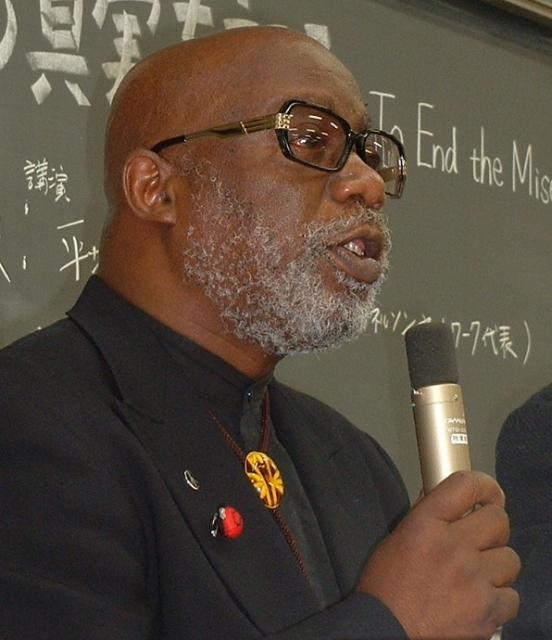

Interview with veteran and peace activist Allen Nelson (pt. 1)

‘YOU WERE NEVER MY ENEMY’:

The Story of Allen Nelson, Vietnam War Veteran and Peace Activist

(part 1)

By Brian Covert

Independent Journalist

TAKARAZUKA, Hyogo, Japan — It is a chilly February evening, and a crowd of local Japanese residents, young and old, men and women, have gathered in a community hall patterned after the city’s most famous landmark, the Takarazuka Revue theater, home to an all-female theatrical company. But unlike the lavish, Broadway-style musicals for which this city is internationally famous, the fare this evening is something far more serious: war, peace and the trashing of Japan’s Constitution.

Allen Nelson is warmly welcomed by the full house of more than 100 people. He goes through a routine that has become familiar to more and more people in Japan and the southern island of Okinawa in the last decade or so: He plays a song, such as “Amazing Grace,” on guitar and harmonica, reads his own account of his life story as published in a book in Japan, quizzes the Japanese audience on the correct way to kill somebody in war as taught by the United States Marine Corps (most audiences fail the quiz), and then afterward takes questions from the audience in which he pulls no punches about the U.S. regarding racism, poverty and war.

The crowd this evening seems especially emotional. Some schoolgirls are quietly crying and one man, in a very “un-Japanese” way, occasionally shouts out in agreement with Nelson as he speaks. Nelson talks about how the U.S. is wrong to wage war in Iraq today, just as it was in Vietnam, where he was sent as a young man more than four decades ago. He urges the members of the Japanese audience to stand up and make their voices heard for peace, especially in protecting the war-renouncing Article 9 clause of Japan’s Constitution, which the Japanese government has been pushing to amend so as to ostensibly allow Japan greater freedom in sending its troops abroad. After Nelson’s speech this night, as with most of his presentations, audience members come up to the front of the room and surround Nelson, shaking his hand and telling him how moved they were by his story.

What seems to move audiences most in Japan and Okinawa are not stories of patriotic bravery and personal sacrifice for one’s country — quite the opposite: It is Allen Nelson’s account of life amidst the death and destruction of war as he experienced it firsthand, a very human story that seems to resonate beyond cultural boundaries. While it is true that many young U.S. soldiers experience war, few of them in our time have experienced it the way Allen Nelson did in Vietnam.

As Nelson tells it, his first lessons in war and violence can be traced to his childhood days growing up in New York City and living the “American Dream” after the Second World War.

Living in America (I)

Allen Nelson: I was born and raised in the slums and ghettos of Brooklyn, New York in 1947, two years after the end of World War II. In these communities there was always lots of violence, unemployment, drug addiction and alcoholism. I was raised by a single parent, my mother, and I had three sisters, so my mother had to feed, clothe and find a shelter for four children by herself. But it was almost impossible.*

When he was six or seven years old, Allen remembers, he beat up the other small kids in his neighborhood if they dared to make racial epithets about his African-American mother’s Asian-looking features. He would come home with his shirt ripped and his head bleeding, and explain to his mother why he was fighting again. “It was very painful for my mom to be teased by these children,” Nelson says, looking back, but that was “a part of the dialogue of America.”

Young Allen was not without his heroes, most of whom were American cowboys: early 1950s characters like the Lone Ranger, Roy Rogers and the Cisco Kid. One day a fat boy in the neighborhood came up to Allen, snatched the cowboy hat off his head and slugged him in the stomach, sending Allen home crying. Allen ran upstairs for support from his grandmother, who was babysitting while his mother was out working. But Allen was instead given a stern warning: “Don’t you ever come in this house crying because some boy hit you.” His grandmother then handed him a baseball bat and gave instructions on how to use it: “Now, you take this bat downstairs and you hit him in the head and you get your hat back, and don’t come in here crying again.” Allen did as he was told, and in the ensuing fight the other boy fled at the sight of his own blood. “That’s sort of the violence, sort of the way that I was born and raised,” Nelson reflects, “and never doubted that there could be alternatives to that type of behavior.”

Allen was always small in stature for his age, but as time went on and he got into sports, he found himself getting good times in running track and field races. He learned how to handle bullies, and admits he later even became a bully himself to other kids.

Like many teenagers, Allen had no time or interest in politics back then; sports, friends and girls beckoned. Nelson remembers one day in the summer of 1963, when he was walking with a girl, a car full of his friends pulled over to the curb and invited him to join them for a road trip to the nation’s capital. He was more interested in taking the girl somewhere for some action, though, and passed up their invitation — and missed joining the historical “March on Washington” at which the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. The day was 28 August 1963.

Allen does remember taking up an invitation one day as a teenager to go listen to another religious minister preach in New York City — and was even more surprised when his protective mother actually allowed him to go there. The place was a curbside stage on 125th Street in front of the famous National Memorial African Bookstore in Harlem. There, the fiery minister scared the teenage Allen Nelson with his strong, straight talk about America’s racial sins. The speaker was Malcolm X.

Allen’s fast times in track caught the attention of local coaches, and by the time Allen entered high school he was already recruited to join the high school track team, where he continued to do well. But one day he pulled a hamstring in his leg; that meant the end of any possible track and field career. Gradually a feeling of being directionless, compounded by the daily pain of poverty in the heart of America’s richest city, left him vulnerable to the idea of pursuing other possibilities — any possibilities. So it was that in the summer of 1965, he passed a U.S. Marine Corps recruiting office in Manhattan, New York, and was lured inside with an offer of free coffee and donuts. There, the quick-talking recruiter showed him, among other things, a poster of a beautiful Asian girl serving a U.S. Marine a nice, cool drink on the golden sands of some island called Okinawa in the Far East, south of Japan. “Where do I sign up?!” was Allen’s reaction. It was not such a great leap for the young man to make, since, he says, “my family were patriots,” with several relatives having had some form of past experience in the U.S. military. In Allen’s family, he says, when your country needed you in a time of war, there was but one choice: “You served.”

In 1965, I dropped out of high school mainly because of poverty, and joined the United States Marine Corps. I was very happy and proud to be a Marine. I remember going home to tell my mother that I had joined the Marine Corps. I thought she would be happy and proud, plus it would be one less mouth that she would have to feed. But my mother was very angry, very disappointed, and she even sat down and started to cry. But to me, my mother just didn’t understand that I was tired of being poor and that the Marine Corps were offering me opportunities that she could not.

To Okinawa

Allen, at age 18, enlisted for four years in the United States Marines, doing most of his basic training at Parris Island, South Carolina, and later some “advanced guerrilla warfare training” at Camp Pendleton near San Diego, California, before shipping off to the Far East.

There were forty young men in my platoon, all 18-year-olds or 19. My drill instructor would stand in front of us and he would say, “What do you want to do?” And we would yell, “Kill.” And he would say, “I can’t hear you!” And then we would yell louder, “Kill!” And then he would say, “I still can’t hear you.” And then we would all scream at the top of our voices, “Kill!” and then we would roar like lions. This is what is means to be a Marine. To be a Marine means that you are going to go into combat and you will kill, and maybe you will die.

Private Allen Nelson’s shooting targets had been bulls-eye targets back in the States, but in Okinawa the targets now were figures of human beings. He knew then, he said, that his chance to kill the enemy would not be far off.

I was stationed at Camp Hansen and during the daytime, we would go into the hills of Okinawa and practice war. The training was very intense. We used live ammunition every day. We worked with tanks and attack helicopters, and practiced how to surround villages without letting people escape.

During the daytime we would go into the hills of Okinawa to practice war. At night we would go back to Camp Hansen. We would take showers, and we would go into town. We would go into town to do three things: to drink, to fight and to look for women. Many times we would get drunk and take taxicabs back to the gate of the camp. We would get out of the cabs, and then refuse to pay the cab drivers. If the cab drivers insisted on being paid, they would be beaten; some were beaten unconscious. When we visited the women and after they delivered their services, many times we would refuse to pay them also. If the women insisted on being paid, they would get the same treatment as the cab drivers received; they would be beaten.

Vietnam

The day came in 1966 for Nelson to be sent to Vietnam with about 1,000 other young men from the U.S.A.

After my training was over in Okinawa, we finally shipped out to Vietnam. I was so excited about going to war that I could barely sleep at night. I was not afraid to go to war. As a boy I had seen many movies about war. And in the movies there was always a handsome hero, beautiful music playing in the background, and the handsome hero always killed his enemy with honor, face to face, and the handsome hero always saved women and children.

Nelson remembers the blast of tropical summer heat that first hit him and his fellow “replacement” soldiers as they filed out of the plane at the U.S. military base in the Vietnamese port city of Da Nang. As he walked across the tarmac, Nelson noticed rows upon rows of coffins draped with American flags, awaiting to be loaded onto the plane heading back. And he saw other Marines, obviously just coming in from battle and heading back home too, laughing at Nelson and his compatriots as they passed by. Nelson wondered what the joke was all about. He would soon find out.

Nelson was standing and talking to a fellow Marine one day in Vietnam when suddenly there was a loud explosion. Nelson, falling to the ground, wiped what he thought was mud from his face. But it was not mud. It was the blown-out brains of the fellow soldier he had been talking to just seconds before.

We would attack the villages early in the morning or very late at night while the people where still asleep. We would set the villages on fire; we would shoot and kill anyone who was on the run. When we attacked the villages in Vietnam, the Vietnamese would grab their guns to fight us. The women would gather all the children and run into the jungles to hide. After we killed the Vietnamese men, we had to go into the jungles to find where the women and children were hiding.

It was always easy to find their hiding places. After three or four days of no water and no rice, the children would be screaming and crying because of the hunger pain. …We would go into the jungle, and stand and listen. Soon we would hear the crying of the children. This would definitely lead us to their hiding place. And the old people, they were too old to run away from machine-gun bullets and attack helicopters. Many of the old people couldn’t even run to keep up with the women and children. So we would find many of the old people in the jungle dead alone or dying alone.

Nelson found that contrary to what he had been led to believe about war in movies and on TV, there was little glory or honor or dignity to be found in the middle of war — especially when it came to innocent victims.

After we attacked the villages, we had to clean up the battlefield, which means we had to gather all the dead people together and count them. The reason why we count the dead people is that we know how many people live in the village, so by counting the dead people, we know how many people have escaped. We would bring the dead people to the middle of the village, and then we would separate them. We put all the men in one pile, all the women in one pile, and all the children in one pile. And of the dead bodies with missing parts like heads, arms or legs, we had to find these parts and put them with the dead bodies that are missing them.

There are two ways of finding the dead people. The first way is to go into the jungle, stand still and listen for flies. If you listen very carefully, you will hear the flies. If you follow the sound, it will lead you to the dead bodies. The second way of finding the dead people is to go into the jungle, and start smelling with your nose. The smell of the rotten bodies is so powerful that it will make your food jump from your stomach to your throat. It will make your eyes water, your nose run, and your whole body weak.

[Killing someone] is a terrible feeling. It’s a sick feeling: your food will not stay down inside of your stomach. In the movies soldiers kill each other and walk away. But in real war you have to go to the people you have killed and touch their body and reach into their pockets for a map or some document. Some Marines would cry and fall to the ground when they saw the bodies they had killed. The military would tell you it was normal when you first killed your enemy but that you would get used to it after you killed more people. But you never get used to killing. Every time you kill someone, you feel deep down inside of you that something important is dying.

[G]oing to the toilet is the most horrifying part of your war experience, because when you go to the toilet in war, you have to separate yourself from your friends, find an isolated place, pull down your pants, and put your weapon down. It is the most horrifying moment.

After we found the women and the children, we would bring them back into the village. They would walk into the village and see the piles of dead bodies. I would see little children run over to the piles of dead women, grabbing on their arms and legs, screaming and crying. And I’d see some of the women run to the children and try to pull them from the bodies. But the children would hold tight to their mothers even though they were dead. And the old people, they would go from pile to pile, identifying their family members. Many of the old people would fall to the ground crying, realizing that there was no one left in their family.

In the total chaos of the U.S. war on the southeast nation of Vietnam, Private Allen Nelson experienced, as he tells it, a moment that would forever change his life.

My Marine company was going through a village, when we were attacked by some Vietnamese soldiers. Many Marines were killed and many were wounded. The rest of us just ran around, trying to find a place of safety. I ran behind a Vietnamese house and ran down into their family bunker.

Once I got down inside of this bunker, I realized that there was someone there with me. I turned and looked. It was a young Vietnamese girl, maybe 15 or 16 years old. When she looked into my face, she was terrified. She looked at me like I was a monster. She was very afraid of me, but for some reason she would not get up and run away. She was breathing very hard, and she was in great pain. So I crawled over to her and realized that she was naked from the waist down. I could not understand what was wrong with her. She kept breathing hard, and she kept making pushing sounds. I looked between her legs, and I saw the little head of a baby.

I didn’t know what was happening to this girl or how to help her, because in the Marine Corps they never taught me how to help bring life into this world. In the Marines they only taught me how to kill.

The girl started to push very hard, and I took my hands and put them between her legs. And to my shock and surprise, a baby came out of her body into my hands. The baby was covered with afterbirth and steam was rising from its body. The girl snatched the baby from my hands. She bit the umbilical cord with her teeth. She wrapped her baby in black rags, and crawled out of the bunker and ran away into the jungle.

At first I could not believe I had witnessed such a thing. But when I looked at my hands, I still had the afterbirth from the baby. When I came out of the bunker, I was a different person. When I joined my Marine friends who had survived the battle, they kept asking me what was wrong, but I never told them about this girl and her baby.

Instinctively, with no proper medical training, Nelson had literally delivered a baby amidst the destruction of a country whose people he knew little about, in a war he had been so eager to take part in. Nelson would go on to feel that that Vietnamese girl and her baby had somehow saved his soul, at a time when he felt he was losing a part of his soul every time he killed a Viet Cong resistance fighter or an innocent Vietnamese villager. Nelson, by his own account, was a changed young man, and soon began seeing the Vietnamese people not as quote-unquote “gooks” or “communists” as most other U.S. soldiers did — but as humans, real people, with families just like his own back home.

After seeing a baby born, I went out of my way to become friends with some Vietnamese people. I would visit their homes and play with their children. Whenever the Vietnamese mothers asked me for things like foods, medicines, blankets, I would steal these things from the military base and give them to the mothers looking after their children.

Nelson was later wounded during fighting and was sent to Japan for medical treatment, ending his 13 months in Vietnam. A combat veteran in 1967 at age 19, he was now left to make sense of all the things he had seen and done in that distant land when he returned to America.

Get Involved

If you'd like to help with maintaining or developing the website, contact us.

Publish

Publish your stories and upcoming events on Indybay.