From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

Portrait of a Palestinian Town

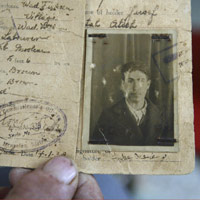

In 1948, the Israeli army marched through Wadi Fukin and forcibly evacuated the small Palestinian town. With no weapons to resist, its residents fled to the surrounding hills. Among them was 25-year-old Yousef Manasra. He and his budding family moved into tents provided by the United Nations. They survived by drinking water from nearby streams and sneaking into their village at night to harvest their fields.

More than once Manasra and the rest of the townspeople tried to return to their homes, only to be driven out again.

“The people of Wadi Fukin were kicked out of their homes so many times, I can’t even count,” Manasra says.

Finally, in 1953, an Israeli border patrol unit dynamited the town, destroying all but a few of the houses.

By that time Manasra was living in the Dheisheh refugee camp a few miles away, near Bethlehem and beyond the border of the new state of Israel. He and thousands of other refugees had been forced to flee their towns by the Israelis.

In 1972, he finally returned home. The camp in Dheisheh was overflowing with refugees from Gaza, so the residents of Wadi Fukin were told to go home.

Neighbors all worked together until new houses were rebuilt. It was the only time, as far as Palestinians can recall, that residents rebuilt a town destroyed in the 1948 Arab-Israeli war.

Today, at 82, Manasra fears history is about to repeat itself in Wadi Fukin. At the end of 2006, Israel’s separation barrier is scheduled to reach this town, which sits just on the Palestinian West Bank side of the Green Line. The barrier will cut off Wadi Fukin and four nearby towns from the rest of the West Bank, which is these towns’ main source for health care, jobs and higher education.

Instead of the 30-foot-high concrete wall in other parts of the West Bank, the barrier around Wadi Fukin will be a complex series of electrified fences, razor wire, motion sensors, military patrol roads and trenches up to 300 feet wide.

The Barrier’s Impact

Manasra and the rest of the 1,200 people who live in the small town will have to pass through two tunnels and a guarded checkpoint to reach Bethlehem. On a good day, officials estimate, the checkpoint alone will take 30 minutes to get through. The entire trip could take hours. If security is escalated, residents could be prevented from crossing altogether.

The wall the Israelis are building now and the town’s being destroyed by them back during the war are the same thing, says Manasra. But this time, he says, instead of two-inch mortars destroying people’s houses, “the wall will destroy people’s will to live here.”

Until the late 1970s, Wadi Fukin and surrounding villages were the breadbasket for Bethlehem. The town grew everything from grapes to cauliflower and eggplant to wheat.

But more recently, because of flying checkpoints, “it’s not feasible for people to work on their land all year long and then simply to be closed off, denied the markets to market their harvest by an Israeli checkpoint,” says Suhail Khalilieh, a research assistant with the Applied Research Institute-Jerusalem, a Palestinian think tank. Unlike permanent barriers, flying checkpoints are mobile -- often nothing more than a military jeep blocking the road -- and they can be set up anywhere at any time.

Many residents have been forced out of farming and into other jobs to make a living. More than half of the men in Wadi Fukin now work either in Israel or in an Israeli settlement. Most of them earn their living working construction. In the Palestinian-controlled areas of the West Bank, only 14 percent of the men from Wadi Fukin still survive in farming.

And many who find work in Israel or Israeli settlements don’t have permits to enter. “Residents of the western rural villages of Bethlehem, or any other Palestinians for that matter, have a financial drain,” says Khalilieh. “Ironically, they have to sneak into Israel to work in settlements or work on the wall.”

Wael Manasra, 34 and the father of four boys, is Yousef Manasra’s grandson. He supports his family by working as a repairman in the Abu Ghneim settlement near Jerusalem. He’s tried twice to get a permit and was turned down both times.

Wael earns about 150 shekels, or $32, each day he works. Along with his father, Ibrahim, who drives a dump truck in the nearby settlement of Betar Illit, Wael helps support his entire extended family of 11 people. Altogether, the family usually lives on about 6,000 shekels a month, or a little over $1,300.

Because it’s too dangerous to sneak into and out of the settlement each day, Wael often stays in the settlement for four or five days at a stretch, hiding at night in any dark nook he can find in one of the buildings where he works. Each night, he sets his cell phone to ring at 12:40 a.m. to warn him that the next shift of guards is coming on duty. They often come looking for workers hiding in the buildings.

“Of course if working in agriculture would allow me to survive, I would stay in Wadi Fukin,” he says. “But it doesn’t.”

The wall also poses a problem for medical care. Wadi Fukin has a medical clinic, but, according to a World Bank study, most people still travel to Bethlehem for major treatments. All the women receive their prenatal care in Bethlehem, and most deliver their children there. When the wall is built and the only access to Bethlehem is through a permanent checkpoint, many fear that during an emergency, they will be unable to reach medical services in time.

There is a school in Wadi Fukin that serves grades K-12, but students must travel to Bethlehem or other West Bank cities to go to college.

Organizing Resistance

Community organizers suspect the barrier will eventually destroy Wadi Fukin’s economy.

“I think the Palestinian people have a high level of resilience, but life in this area is going to be very difficult,” says Ibrahim Ibraigheth, the director of the Community Development Program for the five villages.

Residents have already started resistance efforts. Their first target is the expansion of the Betar Illit Israeli settlement, one of 19 settlements in the area, which sits just to the southeast. Built on land that used to belong to Wadi Fukin and other villages, Betar Illit is home to 26,300 people and scheduled to more than double in population.

Every morning except Saturday, the Jewish Sabbath, the people of Wadi Fukin wake to the sound of jackhammers digging out chunks of the hill to make room for rows of five-story, tan-and-red-roof settlement apartments. The expansion of Betar Illit will encircle Wadi Fukin on the opposite side from the barrier and most likely will cut off the town’s southern exit.

The settlement’s sewage system has already clogged several times, sending raw sewage flowing into Wadi Fukin, ruining valuable farmland. The millions of tons of dirt moved to make room for the new apartment buildings have piled up and threaten to come sliding onto Wadi Fukin’s land, according to villagers.

Along with Friends of the Earth Middle East, an international environmental nonprofit organization, and residents of the nearby Israeli town of Tsur Hadassah, which sits just across the Green Line, activists in Wadi Fukin have hired lawyers to investigate the environmental impacts of the settlement, including increasing strain on the valley’s water resources.

Some Tsur Hadassah residents oppose the barrier as well, and they have circulated a petition asking Israeli officials not to build it or to at least construct it in such a way so as not to affect Wadi Fukin so adversely.

“I didn’t want to feel that I witnessed what was going on and didn’t do anything about it,” says Dudy Yehuda Tzfati, 44, one of several Israeli residents who have mobilized to help. “I feel responsible as an Israeli for what I see as crimes being done in my name.”

What the Future Holds

The Israeli government defends the barrier, saying it’s essential to combating terrorism. “The Security Fence is a central component in Israel’s response to the horrific wave of terrorism emanating from the West Bank, resulting in suicide bombers who enter into Israel with the sole intention of killing innocent people, says Israel’s Ministry of Defense.”

Others, including organizations such as B’tselem, an Israeli human rights group, have argued that rather than basing the route on security concerns, Israel based the route on extraneous considerations completely unrelated to the security of Israeli citizens and that a major aim was to build the barrier east of as many settlements as possible, to make it easier to annex them into Israel.

The United Nations has reported that approximately 5,000 Palestinians already live on land that lies between the barrier and the Green Line. If the barrier follows its planned route, including the sections that are still under consideration, 10 percent of the entire landmass of the West Bank and East Jerusalem, along with nearly 50,000 Palestinians in 38 villages, will be stranded. If Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert follows his proposed plan to make Israel’s permanent border follow the barrier, these areas will be annexed.

The U.N. report also says that in the north, where the wall is already built, access across the barrier has been slow and unreliable. Ibraigheth and Khalilieh fear that if the same is true for Wadi Fukin, much of the town will eventually give up and move to Bethlehem or other cities on the Palestinian side of the barrier in search of a better life.

But Wael Manasra is resolved to stay. “We suffered to return to Wadi Fukin, so I will never go,” he says. “This is my village and my land. Even if I can only eat one small piece of bread, and I can’t get more than this, I will never leave.”

His younger brother, Wisam, doesn’t agree. “If I have to leave to find work, I will, because I think any other life is better than the one here,” he says. “I want to help my family, and I want to help myself.”

Wisam says he might eventually like to return to Wadi Fukin, but he also would like to attend a university and study journalism. And for now, supporting his family is most important. “I feel bad about all of this, working in settlements or leaving,” he says. “But there really isn’t any other way.”

Ibraigheth and Khalilieh believe that if the younger generation decides to leave, much of Wadi Fukin’s land will go uncultivated and could be taken over by Israel. According to the United Nations, Israel uses a law based on an old Ottoman code that allows the state to claim any land that goes uncultivated for three years.

“The older generations are going to be completely isolated,” says Khalilieh. “They will be the only ones there to protect the land, but they will not be able to do so for so many years. That’s when the Israelis will move in and declare the lands as state land under the absentee property law and take it over.”

Some of the younger generation still have hope. Madi Manasra, 13, a cousin of Wael and Wisam, says he wants to finish high school, then attend the university in Bethlehem. He eventually would like to work as a tourist guide. “I’m afraid sometimes the separation will keep me from completing my education,” he says. “But I want to tell people that a just solution is not impossible.”

Others, such as Mohammed Manasra, Wael and Wisam’s youngest brother, see no good options and don’t know what they’ll do. Mohammed wants to be near his family, but fears he’ll never find work. He doesn’t give much thought to attending a university -- or even to what the future may hold.

“With the barrier about to arrive,” he says, “we cannot imagine anything. We cannot dream about anything.”

SOURCES: United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs; PLO Negotiations Affairs Department; Israeli Ministry of Defense; Friends of the Earth Middle East; World Bank; Applied Research Institute-Jerusalem, B’tselem.

--------------

Read more on Israel's Security Barrier.

http://www.pbs.org/frontlineworld/stories/palestine503/sidebar_jakob.html

“The people of Wadi Fukin were kicked out of their homes so many times, I can’t even count,” Manasra says.

Finally, in 1953, an Israeli border patrol unit dynamited the town, destroying all but a few of the houses.

By that time Manasra was living in the Dheisheh refugee camp a few miles away, near Bethlehem and beyond the border of the new state of Israel. He and thousands of other refugees had been forced to flee their towns by the Israelis.

In 1972, he finally returned home. The camp in Dheisheh was overflowing with refugees from Gaza, so the residents of Wadi Fukin were told to go home.

Neighbors all worked together until new houses were rebuilt. It was the only time, as far as Palestinians can recall, that residents rebuilt a town destroyed in the 1948 Arab-Israeli war.

Today, at 82, Manasra fears history is about to repeat itself in Wadi Fukin. At the end of 2006, Israel’s separation barrier is scheduled to reach this town, which sits just on the Palestinian West Bank side of the Green Line. The barrier will cut off Wadi Fukin and four nearby towns from the rest of the West Bank, which is these towns’ main source for health care, jobs and higher education.

Instead of the 30-foot-high concrete wall in other parts of the West Bank, the barrier around Wadi Fukin will be a complex series of electrified fences, razor wire, motion sensors, military patrol roads and trenches up to 300 feet wide.

The Barrier’s Impact

Manasra and the rest of the 1,200 people who live in the small town will have to pass through two tunnels and a guarded checkpoint to reach Bethlehem. On a good day, officials estimate, the checkpoint alone will take 30 minutes to get through. The entire trip could take hours. If security is escalated, residents could be prevented from crossing altogether.

The wall the Israelis are building now and the town’s being destroyed by them back during the war are the same thing, says Manasra. But this time, he says, instead of two-inch mortars destroying people’s houses, “the wall will destroy people’s will to live here.”

Until the late 1970s, Wadi Fukin and surrounding villages were the breadbasket for Bethlehem. The town grew everything from grapes to cauliflower and eggplant to wheat.

But more recently, because of flying checkpoints, “it’s not feasible for people to work on their land all year long and then simply to be closed off, denied the markets to market their harvest by an Israeli checkpoint,” says Suhail Khalilieh, a research assistant with the Applied Research Institute-Jerusalem, a Palestinian think tank. Unlike permanent barriers, flying checkpoints are mobile -- often nothing more than a military jeep blocking the road -- and they can be set up anywhere at any time.

Many residents have been forced out of farming and into other jobs to make a living. More than half of the men in Wadi Fukin now work either in Israel or in an Israeli settlement. Most of them earn their living working construction. In the Palestinian-controlled areas of the West Bank, only 14 percent of the men from Wadi Fukin still survive in farming.

And many who find work in Israel or Israeli settlements don’t have permits to enter. “Residents of the western rural villages of Bethlehem, or any other Palestinians for that matter, have a financial drain,” says Khalilieh. “Ironically, they have to sneak into Israel to work in settlements or work on the wall.”

Wael Manasra, 34 and the father of four boys, is Yousef Manasra’s grandson. He supports his family by working as a repairman in the Abu Ghneim settlement near Jerusalem. He’s tried twice to get a permit and was turned down both times.

Wael earns about 150 shekels, or $32, each day he works. Along with his father, Ibrahim, who drives a dump truck in the nearby settlement of Betar Illit, Wael helps support his entire extended family of 11 people. Altogether, the family usually lives on about 6,000 shekels a month, or a little over $1,300.

Because it’s too dangerous to sneak into and out of the settlement each day, Wael often stays in the settlement for four or five days at a stretch, hiding at night in any dark nook he can find in one of the buildings where he works. Each night, he sets his cell phone to ring at 12:40 a.m. to warn him that the next shift of guards is coming on duty. They often come looking for workers hiding in the buildings.

“Of course if working in agriculture would allow me to survive, I would stay in Wadi Fukin,” he says. “But it doesn’t.”

The wall also poses a problem for medical care. Wadi Fukin has a medical clinic, but, according to a World Bank study, most people still travel to Bethlehem for major treatments. All the women receive their prenatal care in Bethlehem, and most deliver their children there. When the wall is built and the only access to Bethlehem is through a permanent checkpoint, many fear that during an emergency, they will be unable to reach medical services in time.

There is a school in Wadi Fukin that serves grades K-12, but students must travel to Bethlehem or other West Bank cities to go to college.

Organizing Resistance

Community organizers suspect the barrier will eventually destroy Wadi Fukin’s economy.

“I think the Palestinian people have a high level of resilience, but life in this area is going to be very difficult,” says Ibrahim Ibraigheth, the director of the Community Development Program for the five villages.

Residents have already started resistance efforts. Their first target is the expansion of the Betar Illit Israeli settlement, one of 19 settlements in the area, which sits just to the southeast. Built on land that used to belong to Wadi Fukin and other villages, Betar Illit is home to 26,300 people and scheduled to more than double in population.

Every morning except Saturday, the Jewish Sabbath, the people of Wadi Fukin wake to the sound of jackhammers digging out chunks of the hill to make room for rows of five-story, tan-and-red-roof settlement apartments. The expansion of Betar Illit will encircle Wadi Fukin on the opposite side from the barrier and most likely will cut off the town’s southern exit.

The settlement’s sewage system has already clogged several times, sending raw sewage flowing into Wadi Fukin, ruining valuable farmland. The millions of tons of dirt moved to make room for the new apartment buildings have piled up and threaten to come sliding onto Wadi Fukin’s land, according to villagers.

Along with Friends of the Earth Middle East, an international environmental nonprofit organization, and residents of the nearby Israeli town of Tsur Hadassah, which sits just across the Green Line, activists in Wadi Fukin have hired lawyers to investigate the environmental impacts of the settlement, including increasing strain on the valley’s water resources.

Some Tsur Hadassah residents oppose the barrier as well, and they have circulated a petition asking Israeli officials not to build it or to at least construct it in such a way so as not to affect Wadi Fukin so adversely.

“I didn’t want to feel that I witnessed what was going on and didn’t do anything about it,” says Dudy Yehuda Tzfati, 44, one of several Israeli residents who have mobilized to help. “I feel responsible as an Israeli for what I see as crimes being done in my name.”

What the Future Holds

The Israeli government defends the barrier, saying it’s essential to combating terrorism. “The Security Fence is a central component in Israel’s response to the horrific wave of terrorism emanating from the West Bank, resulting in suicide bombers who enter into Israel with the sole intention of killing innocent people, says Israel’s Ministry of Defense.”

Others, including organizations such as B’tselem, an Israeli human rights group, have argued that rather than basing the route on security concerns, Israel based the route on extraneous considerations completely unrelated to the security of Israeli citizens and that a major aim was to build the barrier east of as many settlements as possible, to make it easier to annex them into Israel.

The United Nations has reported that approximately 5,000 Palestinians already live on land that lies between the barrier and the Green Line. If the barrier follows its planned route, including the sections that are still under consideration, 10 percent of the entire landmass of the West Bank and East Jerusalem, along with nearly 50,000 Palestinians in 38 villages, will be stranded. If Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert follows his proposed plan to make Israel’s permanent border follow the barrier, these areas will be annexed.

The U.N. report also says that in the north, where the wall is already built, access across the barrier has been slow and unreliable. Ibraigheth and Khalilieh fear that if the same is true for Wadi Fukin, much of the town will eventually give up and move to Bethlehem or other cities on the Palestinian side of the barrier in search of a better life.

But Wael Manasra is resolved to stay. “We suffered to return to Wadi Fukin, so I will never go,” he says. “This is my village and my land. Even if I can only eat one small piece of bread, and I can’t get more than this, I will never leave.”

His younger brother, Wisam, doesn’t agree. “If I have to leave to find work, I will, because I think any other life is better than the one here,” he says. “I want to help my family, and I want to help myself.”

Wisam says he might eventually like to return to Wadi Fukin, but he also would like to attend a university and study journalism. And for now, supporting his family is most important. “I feel bad about all of this, working in settlements or leaving,” he says. “But there really isn’t any other way.”

Ibraigheth and Khalilieh believe that if the younger generation decides to leave, much of Wadi Fukin’s land will go uncultivated and could be taken over by Israel. According to the United Nations, Israel uses a law based on an old Ottoman code that allows the state to claim any land that goes uncultivated for three years.

“The older generations are going to be completely isolated,” says Khalilieh. “They will be the only ones there to protect the land, but they will not be able to do so for so many years. That’s when the Israelis will move in and declare the lands as state land under the absentee property law and take it over.”

Some of the younger generation still have hope. Madi Manasra, 13, a cousin of Wael and Wisam, says he wants to finish high school, then attend the university in Bethlehem. He eventually would like to work as a tourist guide. “I’m afraid sometimes the separation will keep me from completing my education,” he says. “But I want to tell people that a just solution is not impossible.”

Others, such as Mohammed Manasra, Wael and Wisam’s youngest brother, see no good options and don’t know what they’ll do. Mohammed wants to be near his family, but fears he’ll never find work. He doesn’t give much thought to attending a university -- or even to what the future may hold.

“With the barrier about to arrive,” he says, “we cannot imagine anything. We cannot dream about anything.”

SOURCES: United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs; PLO Negotiations Affairs Department; Israeli Ministry of Defense; Friends of the Earth Middle East; World Bank; Applied Research Institute-Jerusalem, B’tselem.

--------------

Read more on Israel's Security Barrier.

http://www.pbs.org/frontlineworld/stories/palestine503/sidebar_jakob.html

For more information:

http://www.pbs.org/frontlineworld/stories/...

Add Your Comments

Latest Comments

Listed below are the latest comments about this post.

These comments are submitted anonymously by website visitors.

TITLE

AUTHOR

DATE

Becky Johnson has the "journalistic integrity" Sean Hannity She is a zionist propagandist

Sat, May 27, 2006 3:19PM

Film paints emotional portrait but is fundamentally dishonest

Sat, May 27, 2006 2:10PM

Looks interesting

Wed, May 17, 2006 1:18PM

We are 100% volunteer and depend on your participation to sustain our efforts!

Get Involved

If you'd like to help with maintaining or developing the website, contact us.

Publish

Publish your stories and upcoming events on Indybay.

Topics

More

Search Indybay's Archives

Advanced Search

►

▼

IMC Network