From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

SF BAVC Bd Chair Bathsheba Malsheen Involved In Censorship Of Koch Film At PBS/ITVS

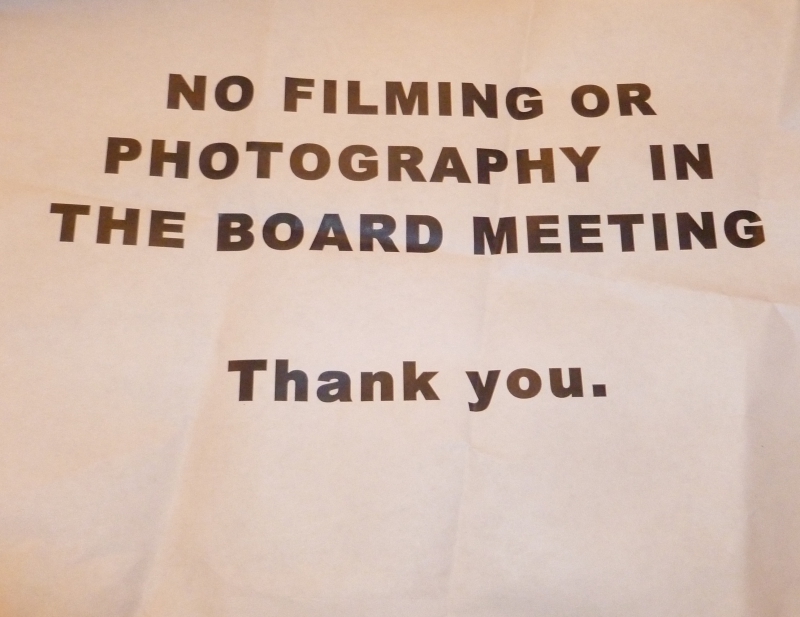

Bathsheba Malsheen who is the chair of the Bay Area Video Coalition and helped privatize San Francisco's Community Access station while using SF city revenue for the operation of BAVC is involved as vice-chair of ITVS in the censorship of a film about the Koch brothers. Malsheen has supported the calling in the SF police against community access producers at their "public board meeting" and has ordered that there can be no video taping of or even photographs of BAVC board meetings. They have also violated the franchise agreement with the city of San Francisco which requires open meetings and posting of minutes.

Did Public Television And ITVS Commit Self-Censorship to Appease Billionaire Funder David Koch?

http://www.democracynow.org/2013/5/30/did_public_television_commit_self_censorship

“A Word from Our Sponsor: Public television’s attempts to placate David Koch.” By Jane Mayer. (The New Yorker)

“Citizen Koch” Film Website

Filmmakers Tia Lessin and Carl Deal say plans for their new documentary to air on public television have been quashed after billionaire Republican David Koch complained about the PBSbroadcast of another film critical of him, "Park Avenue: Money, Power and the American Dream," by acclaimed filmmaker Alex Gibney. Lessin and Deal were in talks to broadcast their film, "Citizen Koch," on PBS until their agreement with the Independent Television Service fell through. The New Yorker reports the dropping of "Citizen Koch" may have been influenced by Koch’s response to Gibney’s film, which aired on PBS stations, including WNET in New York late last year. "Citizen Koch" tells the story of the landmark Citizens United ruling by the Supreme Court that opened the door to unlimited campaign contributions from corporations. It focuses on the role of the Koch-funded Americans for Prosperity in backing Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker, who has pushed to slash union rights while at the same time supporting tax breaks for large corporations. The controversy over Koch’s influence on PBS comes as rallies were held in 12 cities Wednesday to protest the possible sale of the Tribune newspaper chain, including the Los Angeles Times and Chicago Tribune, to Koch Industries, run by David Koch and his brother Charles.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Rallies were held in 12 cities Wednesday to protest the possible sale of the Tribune newspaper chain to the Koch brothers, the billionaire backers of the tea party and other right-wing causes. The Koch brothers are reportedly considering making a bid for the newspaper chain, which would give them control of two of the 10 largest newspapers in the country, theLos Angeles Times and the Chicago Tribune, and two key papers in the battleground state of Florida, the Orlando Sentinel and theSun Sentinel in Fort Lauderdale. Others papers include The Baltimore Sun and the Hartford Courant. A deal could also include Hoy, the second-largest Spanish-language daily newspaper. According to The New York Times, the Koch brothers have quietly discussed purchasing media outlets as part of a long-term strategy to shift the country toward a smaller government with less regulation and taxes.

This is Justin Molito with the Writers Guild of America East at Wednesday’s protest in New York City.

JUSTIN MOLITO: Today we’re out here calling on the equity firm that has stakes within the Tribune Company to not sell to the Koch brothers and not have the L.A. Times, The Baltimore Sun, theOrlando Sentinel and other publications go the way so much of the rest of our media is going, which is under corporate control. And to see that what’s happened recently with the Citizen Koch film should be a warning to everybody in this country that consolidation of corporate power and a free press do not mix in what should be a democracy.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, what happened to the Citizen Koch documentary he refers to is what we’ll look at today. The film tells the story of the landmark Citizens United ruling by the Supreme Court that opened the door to unlimited campaign contributions from corporations. It focuses on the role the Koch brothers-funded group Americans for Prosperity played in backing Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker, who was pushed to slash—who pushed to slash union rights while at the same time supporting tax breaks for large corporations. Citizen Koch was set to air on PBS next fall until its agreement with the Independent Television Service fell through.

AMY GOODMAN: The story of how this happened is detailed in a piece published last week in The New Yorker magazine. Written by Jane Mayer, it’s headlined "A Word from Our Sponsor: Public Television’s Attempts to Placate David Koch." It begins by describing another film critical of the Koch Brothers that did air on PBS, Academy Award-winning director Alex Gibney’s documentary, Park Avenue: Money, Power and the American Dream, which contrasted the lives of residents who live in one of the most expensive apartment buildings in Manhattan, 740 Park Avenue, with those of poor people living at the other end of Park Avenue, in the Bronx. This is a clip from that film.

NARRATOR: This stretch of Park Avenue on the Upper East Side of Manhattan is the wealthiest neighborhood in New York City. This is where the people at the top with the ladder live, the upper crust, the ultra-rich. But this street is about a lot more than money. It’s about political power. The rich here haven’t just used their money to buy fancy cars, private jets and mansions; they have also used it to rig the game in their favor. Over the last 30 years, they’ve enjoyed unprecedented prosperity from a system that they increasingly control.

AMY GOODMAN: In Jane Mayer’s New Yorker article, she details how Neil Shapiro, president ofPBS station WNET here in New York City, called David Koch, a resident of 740 Park Avenue, to warn him that the Alex Gibney film was, quote, "going to be controversial." Koch was a WNET board trustee at the time. Over the years, he has given $23 million to public television. Jane Mayer writes that Shapiro offered to show him the trailer and include him in an on-air discussion that would air immediately after the film. The station ultimately took the unusual step of airing a disclaimer from Koch after the film that called it "disappointing and divisive." Jane Mayer reports this exchange influenced what then happened to Citizen Koch, which was set to be aired on the same PBS series called Independent Lens. The film’s funder and distributor, ITVS, has now said it, quote, "decided not to move forward with the project."

To pick up the rest of this story, we’re joined by the film Citizen Koch's two directors, Tia Lessin and Carl Deal. Their 2008 documentary Trouble the Water was nominated for an Academy Award. It was about Hurricane Katrina. They also worked on Michael Moore's films Bowling for Columbine andFahrenheit 9/11. We reached out to WNET and ITVS, but they declined to join us on the show. We’ll read the statements they sent and play clips from the film Citizen Koch.

But first, we welcome you, Tia and Carl, to Democracy Now!

TIA LESSIN: Thank you so much.

AMY GOODMAN: So, why don’t you tell us about what’s happened to your film? We saw you at the Sundance Film Festival. We always cover the documentary track, and your film, Citizen Koch, was one of those that was premiering at Sundance. Tia, what happened next?

TIA LESSIN: Well, as we were racing to meet the deadline to get to Sundance, actually, is when we started to hear the first rumblings of problems over at ITVS. It was about a week after Alex Gibney’s film aired, and we got a series of frantic phone calls, actually after we decided to change the—to come up with the title Citizen Koch. We had had a working title, Citizen Corp., for our film, but we needed a title to go to Sundance, so we came up with Citizen Koch. They had been fine with that a week earlier. But then we got a frantic series of text messages and phone calls, you know, and they desperately wanted to see the film that we were going to take to Sundance. And we were happy to give it to them. So, I guess a couple days after that, we got on the phone with the head of production over there, and they said, "You know, if you guys don’t change the name of your film, then we’re going to have to take funding away from you. We can’t have a relationship with this film under that name."

And, you know, we were sort of stunned. We were open to other names, you know, quite frankly, but we were really curious about what was behind that. And, look, it took one Google search to figure out that David Koch was a board member of WNET and GBH also, and also a contributor. So we asked, very directly, "Did this have anything to do with the demands they were making?" And, you know, they were not very transparent, but it became clear that, in fact, there was a climate at PBSthat would find the name of this film, Citizen Koch, unacceptable. And we told them, "Look, we’re happy to change the name, but not for political reasons. We’re not going to change the name of our film because one of your donors is going to be angered by it." So, we took a principled stand. We thought that everything would fall apart then and there. We went to Sundance, and they told us before Sundance, "No, we’re still committed to your film. We’re on board with you. We want to see you through this. And we’re still in partnership." So, that’s where the story left off.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, of course, the Jane Mayer article in The New Yorker has pointed out the key role played by Neil Shapiro in beginning to exert pressure on ITVS. Of course, Neil Shapiro had a long career as a network executive at NBC before he came over to run the duopoly, the PBSduopoly in New York. But did you, at that time, get any indication Neil Shapiro was directly intervening?

TIA LESSIN: Look, they weren’t being completely honest with us. They—it was clear that they were afraid of something and somebody. What we now know from Jane Mayer’s article is that Neil Shapiro called ITVS directly and issued some threats, including that they would—that NET would pull out of their series Independent Lens in the aftermath of that Gibney film. And so, I guess they saw our film coming down the pike and freaked out, you know. And it wasn’t just that they wanted us to change the title of the film. It became clear that they wanted us to get—you know, to sanitize the film, to scrub Koch out of the film altogether.

AMY GOODMAN: Carl, can you explain the relationship between ITVS—explain what ITVS is and what PBS is, because you weren’t automatically going on WNET or PBS, but it was your funding and your distribution?

CARL DEAL: Yeah, yeah. The Independent Television Service is—exists to support, financially support, the work of independent filmmakers, and then to advocate for those films that it supports to go on the air on a number of different ways, including their flagship series, which is really the premier showcase for high-quality documentary films, Independent Lens. And so, they have—they’re publicly funded. As far as the way we understand it is their entire budget comes from tax dollars. And, you know, so, they’re good people who have a very, very important mission. And we were really hopeful when all this was going down that they would join with us. We’re willing to fight for this film, and we want people to advocate for it alongside us. This isn’t a film—this isn’t an exposé of the Koch brothers. This is a look at how big money and the money of—ideologically driven money from the wealthiest Americans is drowning out the rest of us.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, I wanted to ask you about the ITVS response.

CARL DEAL: Sure.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: We invited someone from ITVS to appear, but they declined. But they did issue a statement. They said that, quote, "ITVS initially recommended the film Citizen Corp for production licensing based on a written proposal. Early cuts of the film, including the Sundance version, did not reflect the proposal, however, and ITVS eventually withdrew its offer of a production agreement to acquire public television exhibition rights. The film was neither contracted nor funded" by ITVS. Your response?

CARL DEAL: Stunning. Stunning. We were really disappointed, that we have an opportunity right now for ITVS to engage in a really important conversation about who has influence over what goes on the public airwaves. You know, PBS was set up, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, to serve the public interest, not private interests. And so, we’re really disappointed with that statement, because when ITVS came in and decided to become a production partner with us, we were a year into production. We had our characters cast. We had our story lines. We presented them with written proposals, with video proposals, that completely reflect the film that we delivered. The only thing that changed, from the time that they saw a rough cut of the film and the time we got into Sundance and these series of strange meetings started to happen, was Alex Gibney’s film aired.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, we asked both ITVS and PBS to join us. Let me read the response, the statement from the New York PBS station WNET that aired the Alex Gibney documentary, Park Avenue: Money, Power and the American Dream, last November, but drew criticism for giving David Koch advance notice and running his response immediately after the film, along with a round table discussion. They did decline our invitation to come on the program, but wrote, quote, "We have previously used round table discussion segments to expand on programming covering controversial topics, and we invited Mr. Koch and Senator Schumer (the two main characters in the film) to participate." The statement also said, quote, "With regard to the film 'Citizen Koch', no one at WNETknew anything about this film and never had any discussions about it with ITVS or any other entity." Your response to that, Tia Lessin?

TIA LESSIN: I have no doubt that NET, you know, saw it—didn’t see it. I mean, I don’t think Koch saw it. That’s how insidious this is. You know, David Koch doesn’t need to pick up the phone and yell at anybody. He just has to tap his wallet, and, you know, our film disappears.

AMY GOODMAN: In fact, he did quit the board. He resigned from WNET just a week or two ago.

TIA LESSIN: That’s right.

AMY GOODMAN: And was a major donor, what, has overall given something like $23 million.

TIA LESSIN: That’s right, tax-deductible dollars, you know? And in exchange for that, apparently he has some role in programming decisions over at NET, and I think that’s really unacceptable.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: So, in essence, what we’re looking at here is not necessarily a direct intervention by Koch, but self-censorship by the public television community in an effort to prevent someone like Koch from pulling their dollars out.

TIA LESSIN: That’s right. That’s right.

CARL DEAL: Yeah, yeah.

TIA LESSIN: Well, and, actually, I think why does somebody like David Koch make such a major contribution to public broadcasting, when in fact he’s against public institutions like public broadcasting? I think it probably has to do with having some influence over what gets said on the public airwaves.

AMY GOODMAN: You were at the protest yesterday here in New York. There were protests around the country around the issue of the Kochs buying newspapers like the Los Angeles Times. What connection do you see here, Carl?

CARL DEAL: Well, look, we didn’t enter into this conversation lightly, but our experience, we feel that our film was censored, and it was due to the presence of David Koch on the board. And there’s a lot of discussion right now over whether or not private ownership of newspapers has an influence on how the news gets reported. And we just feel like our recent experience sheds light on that. If there were ever any doubts, in this case, whether or not David Koch directly intervened, his mere presence had an impact on the public discourse.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to break, and then, when we come back, talk about the content of your film, Citizen Koch. This is Democracy Now! Back in a minute.

ITVS Board Of Directors

http://www.itvs.org/about/board/

Board of Directors

Chair

Garry Denny

Director of Programming

Wisconsin Public Television

Madison, WI

Vice Chair

Bathsheba Malsheen

President and CEO

MiNo Wireless

Santa Clara, CA

Secretary

Malinda Maynor Lowery

Assistant Professor of History

University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill

Chapel Hill, NC

Treasurer

Robb Moss

Lecturer

Harvard University

Cambridge, MA

Executive Committee

Lisa Cortés

President

Cortés Films

New York, NY

Executive Committee

Cheryl Head

Chief Operating Officer

Livingston Associates

Baltimore, MD

Members

Sharese Bullock-Bailey

Producer; Strategic Consultant

Brooklyn, NY

Beth Curley

President and CEO

Nashville Public Television

Nashville, TN

Tracy Fullerton

Associate Professor

USC School of Cinematic Arts

Los Angeles, CA

Ian Inaba

Executive Director

Citizen Engagement Lab

Berkeley, CA

Marie Nelson

Senior Director and Executive Producer

of News and Original Programming

BET Networks

Washington, DC

Jean Tsien

Producer, Editor

Forest Hills, NY

Margaret Wilkerson

Professor Emerita

University of California-Berkeley

Kensington, CA

Read the most recent board of directors meeting minutes

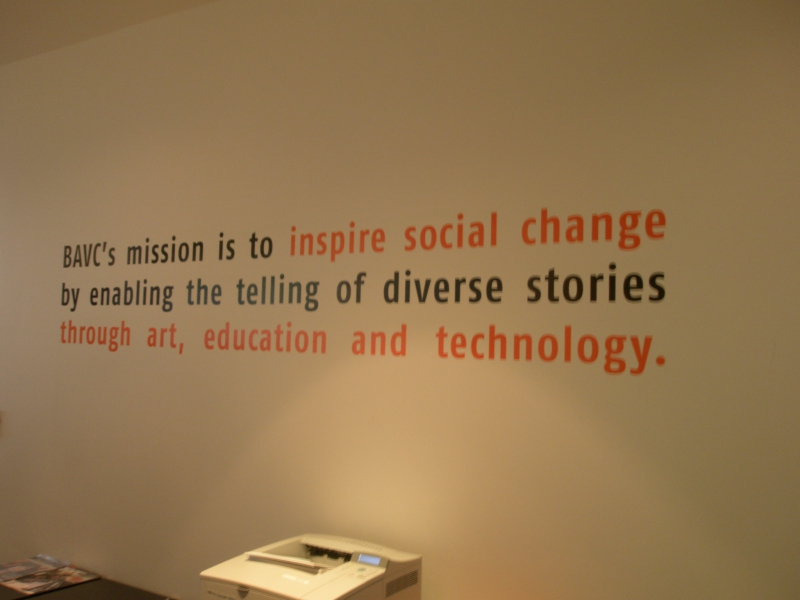

Bay Area Video Coalition Which Manages San Francisco Community College Channel

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Dr. Bathsheba Malsheen, Board President

Dr. Bathsheba Malsheen is BAVC's Board President and has served as CEO of several mobile technology companies. Most recently, she was president and CEO of MINO Wireless, which provided managed global roaming services for mobile operators. Dr. Malsheen was previously CEO at Groove Mobile, the world's leading mobile music service provider and CEO of Voxware, a global provider of mobile voice-based enterprise solutions for distribution and warehouse operations. She currently serves as a Board Member of Independent Television Service (ITVS) and Board Advisor to SoundHound, producing applications in audio and music identification, voice recognition and search technologies. Dr. Malsheen holds a BA from Hofstra University, and an MA and PhD from Brown University in Linguistics.

Neil O’Donnell, Vice President

Neil O’Donnell, BAVC's Board Vice President, is a founding partner of the San Francisco and Washington, D.C. law firm Rogers Joseph O'Donnell where he is co-chair of the government contracts and construction practice groups. He has been consistently named one of the leading government contract lawyers in the country by Chambers USA, America's Leading Lawyers for Business. Neil serves on the Advisory Committee for The Government Contractor and on the Associated General Contractors of California Legal Advisory Committee, and is a member of the ABA’s Section of Public Contract Law and Forum Committee on the Construction Industry. He holds a JD from Yale Law School, and a BA from Williams College.

Jason Kipnis, Board Treasurer

Jason Kipnis, BAVC's Board Treasurer, manages the Intellectual Property (IP) Counseling practice in the Silicon Valley Office of Weil, Gotshal & Manges, and has extensive experience in patent portfolio management, IP litigation and pre-litigation counseling, IP due diligence, and IP transactions. Jason is also an adjunct lecturer at Stanford Law School, where he teaches IP Strategy for High Technology Companies, and is a frequent speaker on intellectual property matters at professional and academic conferences. In addition, he has been selected by the IAM250 as one of the world’s leading IP strategists. Jason holds a JD from Stanford Law School, and an SB and SM from Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Angela Jones

Angela Jones is currently a Program Specialist with Northern California Grantmakers, responsible for developing skill-building workshops to enhance the effectiveness of grantmaking professionals and formerly worked at The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation its Conflict Resolution Program. She holds a BA from the University of California-Berkeley and is pursuing an MBA in Finance and Marketing at Mills College in Oakland. Angela also serves on the advisory board for Chicken & Egg Pictures, a hybrid film fund and non-profit production company dedicated to supporting women filmmakers who are as passionate about the craft of storytelling as they are about the social justice, environmental and human rights issues they are exploring on film.

The BAVC Board of Directors is always seeking interested candidates and suggests that interested members of the community contact info [at] bavc.org with a bio and letter of interest.

With over 100 public and educational channels disappearing since the mid-2000s, we need to have a big rethink about quality public-access TV.The Cable TV Access Crisis

http://www.alternet.org/media/151905/the_cable_tv_access_crisis?page=entire

August 7, 2011 |

Public-access television has always had a low-budget, amateur reputation. Yet Rod Laughridge's alternative news program "Newsroom on Access SF" was anything but that. Though San Francisco's public-access station had its share of offbeat shows —- like the risqué DeeDeeTV, hosted by self-described "pop culture diva" Dee Dee Russell — "Newsroom" took itself seriously. Its mission, as described on its website, was to "bring community-based, community reported and produced independent news and interviews from a grassroots viewpoint — unhindered, uncensored and unaltered."

The show, which ran for five years on Channel 29, followed a professional news format with high production values. Anchors reported headlines from behind a studio desk as video streams played in the background. Local news segments on topics like the plight of renters and live reports from homeless shelters were interspersed with commentary by the likes of Mumia Abu-Jamal and Angela Davis, and international news from Al-Jazeera. During its run, "Newsroom" was nominated for an Emmy and won several Western Access Video Excellence (WAVE) awards. "It was a full-blown news show," Laughridge recalls.

Unfortunately, "Newsroom" became a casualty of a ripple effect brought on by the passage of a bill that slashed the public-access operating budget across California. This resulted in a new provider, the Bay Area Video Coalition (BAVC), which had no prior experience operating public TV, taking over SF's two public-access channels. BAVC closed the production studio where "Newsroom" and other shows were produced and instituted a different model that did away with the traditional three-camera set-up. Laughridge notes that, in the old days, staff members assisted public-access producers with editing. Now "you have to pay for [BAVC's] classes to do that. There's a conflict right there," he says. These changes to the public-access model effectively "killed the idea of community" in community television, Laughridge says.

The loss of an award-winning program like "Newsroom," which provided a viable, community-based alternative to network TV news, symbolizes one of the clearest examples of what has transpired as a result of the public-access crisis. As the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) noted in its 2011 media review, "State and local changes have reduced the funding and, in some cases, the prominence on the cable dial of public, educational and government channels (PEG) at a time when the need for local programming is especially urgent."

The Perils of PEG Centers

The public-access crisis in California was brought about by the 2006 passage of the Digital Infrastructure and Video Competition Act (DIVCA), a bill that was heavily lobbied for by Comcast and AT&T. According to the telecommunications industry, DIVCA was supposed to create jobs, increase competition and serve the public interest. Its actual effect was the exact opposite — cable companies eliminated jobs and ultimately faced less competition from the defunding of community television stations. As of 2009, similar bills had been passed in 25 states, with similar results.

Since the mid-2000s, more than 100 PEG stations across the country have disappeared; cities like San Francisco and Seattle have cut as much as 85 percent of the PEG operations budget. City funding for public access has been entirely eliminated in Denver and Dallas; at least 45 such stations have closed in California since 2006-12 in Los Angeles, the nation's No. 3 media market, alone. As many as 400 PEG stations in Wisconsin, Florida, Missouri, Iowa, Georgia and Ohio are facing extinction as well.

Moreover, according to a 2010 study by the Benton Foundation, these cuts have disproportionately affected minority communities. Adding insult to injury, AT&T and other cable providers have employed what's known as "channel-slamming": listing all public-access channels on a single channel or making them accessible only in submenus, which makes finding them difficult for viewers.

A bill currently before the House of Representatives called the Community Access Preservation, or CAP, Act, could prevent hundreds of funding-challenged PEG stations nationwide from going belly up. The bill limits channel-slamming and would amend an FCC ruling that PEG support may be used only for facilities and equipment, and not for operating expenses. Even if the CAP Act passes, it "won't solve all of public-access TV's problems," says Media Alliance executive director Tracy Rosenberg. For one thing, the CAP Act falls short of mandating a higher percentage of cable franchise fees — an estimated $10 million to $12 million in SF — for PEG operators. Increasing this revenue, however, could allow PEG stations not only to survive, but to thrive.

An Open-Source Solution?

One possible solution for financially challenged PEG stations is the development of open-source or user-modifiable software — a model currently being developed in Denver, San Francisco and several other cities. In just its second year of operating SF Commons — SF's public-access station — BAVC is already attracting wider attention. In June 2011, the organization was singled out for praise by the FCC, which called SF Commons one of the "most promising templates for the future of public-access centers."

Open source offers built-in internet connectivity and is less financially constraining than the old public-access model, requiring less equipment and less staff. Instead of reels of videotape or DVDs, programs are saved as MPEG files. Editing workstations aren't bulky analog machines but svelte Macintosh computers equipped with Final Cut Pro editing software.

Yet open source isn't a perfect solution. In the short-term, moving to an open-source model for public access may actually widen the gap affecting underserved and less technologically literate demographics. "Seniors, disabled, low-income adults," Rosenberg charges, "[are] being left off the train."

Adapting open source to a public-access medium also limits the potential of users to acquire skills needed for some television jobs and puts more emphasis on offsite production, which in turn reduces the level of interaction between programmers. "They want you to edit at home," Laughridge says. "There's the digital divide right there: Not everyone has a computer or camera."

Virtual Community vs. Actual Community

Laughridge is one of several veteran public-access programmers who complain about displacement under BAVC.

Ellison Horne, a former president of Channel 29's Community Advisory Board (CAB), says BAVC made an "aggressive move toward a virtual studio as opposed to what we had before, which was a community media center." This resulted, he says, in a lack of community engagement.

Since BAVC's takeover of Channel 29, "a very different culture has emerged" in San Francisco public access, says documentary filmmaker Kevin Epps, who began his career in public access. That culture is more conservative, tech-savvy, youth-oriented and, in Horne's words, "elitist."

Steve Zeltzer, a labor activist and public-access producer, charges the BAVC takeover has resulted in "the privatization of public access."

Ken Johnson, who worked for a stint as a producer-director at local station KQED after getting his start on Channel 29, credits public-access TV with helping him stay off the streets and out of jail. Johnson says he often rounded up street people as volunteers to help him produce his show on veterans' issues. But volunteers are no longer welcome under BAVC's operatorship.

Instead of a community-supportive environment, Johnson says, "They have this robotic thing when you do it like that, you lose something."

BAVC staff are quick to characterize the problems with public-access programmers as simply a case of the old guard being resistant to change. "You had a lot of producers used to doing the same routine for X amount of years," says Andy Kawanami, SF Commons' community manager. He concedes the transition to open source wasn't completely smooth, but says things "have settled down quite a bit" since.

Former BAVC executive director Ken Ikeda has been quoted as saying, "We've learned the hard way what innovation in isolation can cost an organization." And Jen Gilomen, BAVC's director of public Media Strategies, admits "we've lost some people" in the transition. However, she says, the economic reality means "the whole model had to change."

Making Open Source Work for Everybody

A considerable learning curve is involved in adapting open source to public-access television, says Tony Shawcross, Executive Director of Denver Open Media (DOM). After taking over Denver's PEG channel in 2005, DOM underwent a period of trial-and-error, discovering what worked and what didn't. In 2008, DOM received a $400,000 Knight Foundation grant which allowed it to revise its model to make it more community- and user-friendly.

"We had to go through that process in order to learn what it took to make the tools work for others," he says. Overall, Shawcross says DOM isn't reaching as wide a constituency as its predecessor, but, he adds, "You can't just talk about diversity and our model without also talking about money. Dollar-for-dollar, I'd say DOM is doing better in reaching disadvantaged communities, but we'd be doing much better if we had $500,000 annually to invest in serving the communities who are most in need."

BAVC, Shawcross says, is "one of the few success stories in public access." However, he says, BAVC "are very focused on their own needs, and the development work they're doing in open source is not focused on benefitting the rest of the community as much as it would if that were a true priority for them."

BAVC is "one of the few success stories in public access," Shawcross says, but it's "very focused on their own needs, and the development work they're doing in open source is not focused on benefiting the rest of the community as much as it would if that were a true priority for them."

Currently, BAVC has no initiatives "specific to diversity," says Gilomen. Yet BAVC has made forays into community outreach via the Neighborhood News Network (n3), three partnership pilot programs with nonprofit centers utilizing these centers' media production facilities. Ultimately, the FCC notes, n3 "will link PEG channels to 15 community sites throughout the city, using an existing fiber network." After airing on SF Commons, these programs will be accessible to viewers as one of BAVC's online channels.

Although they've made for good PR copy on BAVC's website, the three n3 programs have thus far resulted in a total of just 77 minutes of actual on-air programming. "We need more money to expand these programs," Gilomen says, which she hopes "will seed news bureaus."

With a single-camera studio set-up, n3's no-frills production values lag behind the standard set by "Newsroom." At times, the content resembles infomercials for BAVC's community partner organizations. In the Mission District's n3 pilot episode, anchor Naya Buric, a BAVC intern, repeatedly stumbles over her words, at one point misidentifying n3 as "neighborhood network news." When asked what difference n3 will make to the community, guest Jean Morris touts the Mission Cultural Center for Latino Arts' programming, yet fails to mention any issues of substance affecting the neighborhood, such as gentrification and gang violence. The Bayview-Hunters Point pilot show, meanwhile, features members of the Boys and Girls Club, aged 9-12, covering the club's own Junior Giants program. The South of Market pilot fares a little better, with segments on redevelopment, a fire at a single-room occupancy hotel and the availability of bathrooms for SF's homeless population. It remains to be seen whether n3 programs can fill the role "Newsroom" used to play, much less consistently cover topics of serious concern to neighborhood residents. Willie Ratcliffe, publisher of independent African-American newspaper SF BayView, recognizes the n3 program in Bayview-Hunters Point as a positive development for a handful of young people. However, he says, "I don't see where it's gonna do too much" to address the "burning issue [of] economic survival," nor the police brutality, health issues and environmental concerns Bayview residents face daily. In his view, the smiling African-American faces pictured on BAVC's website are "just being used, really," he says.

The Hope of Digital Integration

Two years after launching SF Commons, the station is still very much a work in progress. The lack of a consistent program schedule, some producers say, makes it difficult to build a regular audience. But Gilomen says this concern will be addressed in the coming months as BAVC rolls out a new set of web-based tools allowing producers to self-schedule their programs and archive content online. Besides eliminating the need for physical DVDs, this makes it possible for public-access stations in other markets to air SF Commons' content.

However, the true test of BAVC's public-access stewardship is yet to come. SF Commons features prominently in a SF Department of Technology (SFDOT) broadband inclusion initiative, which, if successful, could form the 21st century model for public access in America.

In addition to the operating budget of $170,000 for two PEG channels from SFDOT, BAVC is also the recipient of $2 million in technology grants specifically tied to broadband initiatives aimed at increasing digital literacy. But while the potential for using digitally integrated public-access and broadband services to close the digital divide exists on paper, these services haven't been implemented in a concrete, tangible way — with measurable results — yet.

SFDOT policy analyst Brian Roberts uses buzzwords like "digital inclusion" and "affordable access" in describing the city's B-TOP program, which envisions the creation of a "public broadband space" (PBS) incorporating public access as one of its components. The idea of a PBS is "having access to training and technology people couldn't afford in their homes," Roberts explains. But, he says, "we're not sure where that's going to go."

The B-TOP program relies on federal grants and matching funds for its S10 million budget. So far it's created a handful of new bureaucratic positions, doled out tens of thousands of dollars to BAVC for equipment purchases, started a digital media skills training course at City College of San Francisco and held several community outreach events. Yet it's had little to no impact on improving access in SF's most technologically underserved neighborhoods, which is what it's supposed to do. According to SFDOT's most recent report on sustainable broadband adoption, the program is only 1 percent complete at this time. SFDOT has failed to meet its baseline goals for new subscribers receiving discounted broadband service; currently there are "zero" households and "zero" businesses participating, which it blames on "implementation delays."

In other words, despite the FCC's flowery praise for BAVC and SFDOT's collaborative efforts, the vision of a fiber-optic network broadcasting hyperlocalized content over public-access airwaves isn't crystal clear.

An Upside Down Model?

While SFDOT and BAVC wait for the sustainable broadband initiative to take shape, a cadre of veteran video producers are attempting to fashion their own template for public access's immediate future.

Instead of relying on technology grants based around not-quite-there-yet initiatives, this model would pool the existing resources of several cities in Contra Costa County, each of whom receive PEG funding from cable operators, to create a countywide community media center. Instead of just under $200,000 in operating expenses, the center's budget could be closer to $2 million, enough to run a top-notch PEG center with high-quality production values. This center would be run not by outside operators, but by the producers themselves, fulfilling one of the FCC's recommendations for high-performing PEGS: "the ceding of editorial control to producers."

Could a super-PEG center serving the needs of an entire county, rather than an aggregation of smaller PEGS tied to specific cities, be a way to ensure the future of public access while preserving its vibrant culture?

Sam Gold, the man behind the effort, thinks so. He's assembled a team consisting of several former SF public-access producers and is actively pursuing getting the necessary approval from various city councils. He calls the effort "an upside down model," since he's invested $40,000 of his own money into equipment. In his mind, they key question is to whether the center can be established on public space, which would alleviate the biggest operating cost, that of renting a facility. If successful, Gold's model could be replicated in other markets, offering a third option to the public-access crisis besides ceasing operations or acquiescing to the imperfections of open source. "Wonder if we can get the old 'Newsroom' crew back together?" Gold ponders during a lunch with Laughridge and several other public-access veterans. Laughridge just looks at him and smiles.

Eric K. Arnold wrote this story as part of a series produced by the G.W. Williams Center for Independent Journalism for a media policy fellowship sponsored by The Media Consortium

http://www.democracynow.org/2013/5/30/did_public_television_commit_self_censorship

“A Word from Our Sponsor: Public television’s attempts to placate David Koch.” By Jane Mayer. (The New Yorker)

“Citizen Koch” Film Website

Filmmakers Tia Lessin and Carl Deal say plans for their new documentary to air on public television have been quashed after billionaire Republican David Koch complained about the PBSbroadcast of another film critical of him, "Park Avenue: Money, Power and the American Dream," by acclaimed filmmaker Alex Gibney. Lessin and Deal were in talks to broadcast their film, "Citizen Koch," on PBS until their agreement with the Independent Television Service fell through. The New Yorker reports the dropping of "Citizen Koch" may have been influenced by Koch’s response to Gibney’s film, which aired on PBS stations, including WNET in New York late last year. "Citizen Koch" tells the story of the landmark Citizens United ruling by the Supreme Court that opened the door to unlimited campaign contributions from corporations. It focuses on the role of the Koch-funded Americans for Prosperity in backing Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker, who has pushed to slash union rights while at the same time supporting tax breaks for large corporations. The controversy over Koch’s influence on PBS comes as rallies were held in 12 cities Wednesday to protest the possible sale of the Tribune newspaper chain, including the Los Angeles Times and Chicago Tribune, to Koch Industries, run by David Koch and his brother Charles.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Rallies were held in 12 cities Wednesday to protest the possible sale of the Tribune newspaper chain to the Koch brothers, the billionaire backers of the tea party and other right-wing causes. The Koch brothers are reportedly considering making a bid for the newspaper chain, which would give them control of two of the 10 largest newspapers in the country, theLos Angeles Times and the Chicago Tribune, and two key papers in the battleground state of Florida, the Orlando Sentinel and theSun Sentinel in Fort Lauderdale. Others papers include The Baltimore Sun and the Hartford Courant. A deal could also include Hoy, the second-largest Spanish-language daily newspaper. According to The New York Times, the Koch brothers have quietly discussed purchasing media outlets as part of a long-term strategy to shift the country toward a smaller government with less regulation and taxes.

This is Justin Molito with the Writers Guild of America East at Wednesday’s protest in New York City.

JUSTIN MOLITO: Today we’re out here calling on the equity firm that has stakes within the Tribune Company to not sell to the Koch brothers and not have the L.A. Times, The Baltimore Sun, theOrlando Sentinel and other publications go the way so much of the rest of our media is going, which is under corporate control. And to see that what’s happened recently with the Citizen Koch film should be a warning to everybody in this country that consolidation of corporate power and a free press do not mix in what should be a democracy.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, what happened to the Citizen Koch documentary he refers to is what we’ll look at today. The film tells the story of the landmark Citizens United ruling by the Supreme Court that opened the door to unlimited campaign contributions from corporations. It focuses on the role the Koch brothers-funded group Americans for Prosperity played in backing Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker, who was pushed to slash—who pushed to slash union rights while at the same time supporting tax breaks for large corporations. Citizen Koch was set to air on PBS next fall until its agreement with the Independent Television Service fell through.

AMY GOODMAN: The story of how this happened is detailed in a piece published last week in The New Yorker magazine. Written by Jane Mayer, it’s headlined "A Word from Our Sponsor: Public Television’s Attempts to Placate David Koch." It begins by describing another film critical of the Koch Brothers that did air on PBS, Academy Award-winning director Alex Gibney’s documentary, Park Avenue: Money, Power and the American Dream, which contrasted the lives of residents who live in one of the most expensive apartment buildings in Manhattan, 740 Park Avenue, with those of poor people living at the other end of Park Avenue, in the Bronx. This is a clip from that film.

NARRATOR: This stretch of Park Avenue on the Upper East Side of Manhattan is the wealthiest neighborhood in New York City. This is where the people at the top with the ladder live, the upper crust, the ultra-rich. But this street is about a lot more than money. It’s about political power. The rich here haven’t just used their money to buy fancy cars, private jets and mansions; they have also used it to rig the game in their favor. Over the last 30 years, they’ve enjoyed unprecedented prosperity from a system that they increasingly control.

AMY GOODMAN: In Jane Mayer’s New Yorker article, she details how Neil Shapiro, president ofPBS station WNET here in New York City, called David Koch, a resident of 740 Park Avenue, to warn him that the Alex Gibney film was, quote, "going to be controversial." Koch was a WNET board trustee at the time. Over the years, he has given $23 million to public television. Jane Mayer writes that Shapiro offered to show him the trailer and include him in an on-air discussion that would air immediately after the film. The station ultimately took the unusual step of airing a disclaimer from Koch after the film that called it "disappointing and divisive." Jane Mayer reports this exchange influenced what then happened to Citizen Koch, which was set to be aired on the same PBS series called Independent Lens. The film’s funder and distributor, ITVS, has now said it, quote, "decided not to move forward with the project."

To pick up the rest of this story, we’re joined by the film Citizen Koch's two directors, Tia Lessin and Carl Deal. Their 2008 documentary Trouble the Water was nominated for an Academy Award. It was about Hurricane Katrina. They also worked on Michael Moore's films Bowling for Columbine andFahrenheit 9/11. We reached out to WNET and ITVS, but they declined to join us on the show. We’ll read the statements they sent and play clips from the film Citizen Koch.

But first, we welcome you, Tia and Carl, to Democracy Now!

TIA LESSIN: Thank you so much.

AMY GOODMAN: So, why don’t you tell us about what’s happened to your film? We saw you at the Sundance Film Festival. We always cover the documentary track, and your film, Citizen Koch, was one of those that was premiering at Sundance. Tia, what happened next?

TIA LESSIN: Well, as we were racing to meet the deadline to get to Sundance, actually, is when we started to hear the first rumblings of problems over at ITVS. It was about a week after Alex Gibney’s film aired, and we got a series of frantic phone calls, actually after we decided to change the—to come up with the title Citizen Koch. We had had a working title, Citizen Corp., for our film, but we needed a title to go to Sundance, so we came up with Citizen Koch. They had been fine with that a week earlier. But then we got a frantic series of text messages and phone calls, you know, and they desperately wanted to see the film that we were going to take to Sundance. And we were happy to give it to them. So, I guess a couple days after that, we got on the phone with the head of production over there, and they said, "You know, if you guys don’t change the name of your film, then we’re going to have to take funding away from you. We can’t have a relationship with this film under that name."

And, you know, we were sort of stunned. We were open to other names, you know, quite frankly, but we were really curious about what was behind that. And, look, it took one Google search to figure out that David Koch was a board member of WNET and GBH also, and also a contributor. So we asked, very directly, "Did this have anything to do with the demands they were making?" And, you know, they were not very transparent, but it became clear that, in fact, there was a climate at PBSthat would find the name of this film, Citizen Koch, unacceptable. And we told them, "Look, we’re happy to change the name, but not for political reasons. We’re not going to change the name of our film because one of your donors is going to be angered by it." So, we took a principled stand. We thought that everything would fall apart then and there. We went to Sundance, and they told us before Sundance, "No, we’re still committed to your film. We’re on board with you. We want to see you through this. And we’re still in partnership." So, that’s where the story left off.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, of course, the Jane Mayer article in The New Yorker has pointed out the key role played by Neil Shapiro in beginning to exert pressure on ITVS. Of course, Neil Shapiro had a long career as a network executive at NBC before he came over to run the duopoly, the PBSduopoly in New York. But did you, at that time, get any indication Neil Shapiro was directly intervening?

TIA LESSIN: Look, they weren’t being completely honest with us. They—it was clear that they were afraid of something and somebody. What we now know from Jane Mayer’s article is that Neil Shapiro called ITVS directly and issued some threats, including that they would—that NET would pull out of their series Independent Lens in the aftermath of that Gibney film. And so, I guess they saw our film coming down the pike and freaked out, you know. And it wasn’t just that they wanted us to change the title of the film. It became clear that they wanted us to get—you know, to sanitize the film, to scrub Koch out of the film altogether.

AMY GOODMAN: Carl, can you explain the relationship between ITVS—explain what ITVS is and what PBS is, because you weren’t automatically going on WNET or PBS, but it was your funding and your distribution?

CARL DEAL: Yeah, yeah. The Independent Television Service is—exists to support, financially support, the work of independent filmmakers, and then to advocate for those films that it supports to go on the air on a number of different ways, including their flagship series, which is really the premier showcase for high-quality documentary films, Independent Lens. And so, they have—they’re publicly funded. As far as the way we understand it is their entire budget comes from tax dollars. And, you know, so, they’re good people who have a very, very important mission. And we were really hopeful when all this was going down that they would join with us. We’re willing to fight for this film, and we want people to advocate for it alongside us. This isn’t a film—this isn’t an exposé of the Koch brothers. This is a look at how big money and the money of—ideologically driven money from the wealthiest Americans is drowning out the rest of us.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, I wanted to ask you about the ITVS response.

CARL DEAL: Sure.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: We invited someone from ITVS to appear, but they declined. But they did issue a statement. They said that, quote, "ITVS initially recommended the film Citizen Corp for production licensing based on a written proposal. Early cuts of the film, including the Sundance version, did not reflect the proposal, however, and ITVS eventually withdrew its offer of a production agreement to acquire public television exhibition rights. The film was neither contracted nor funded" by ITVS. Your response?

CARL DEAL: Stunning. Stunning. We were really disappointed, that we have an opportunity right now for ITVS to engage in a really important conversation about who has influence over what goes on the public airwaves. You know, PBS was set up, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, to serve the public interest, not private interests. And so, we’re really disappointed with that statement, because when ITVS came in and decided to become a production partner with us, we were a year into production. We had our characters cast. We had our story lines. We presented them with written proposals, with video proposals, that completely reflect the film that we delivered. The only thing that changed, from the time that they saw a rough cut of the film and the time we got into Sundance and these series of strange meetings started to happen, was Alex Gibney’s film aired.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, we asked both ITVS and PBS to join us. Let me read the response, the statement from the New York PBS station WNET that aired the Alex Gibney documentary, Park Avenue: Money, Power and the American Dream, last November, but drew criticism for giving David Koch advance notice and running his response immediately after the film, along with a round table discussion. They did decline our invitation to come on the program, but wrote, quote, "We have previously used round table discussion segments to expand on programming covering controversial topics, and we invited Mr. Koch and Senator Schumer (the two main characters in the film) to participate." The statement also said, quote, "With regard to the film 'Citizen Koch', no one at WNETknew anything about this film and never had any discussions about it with ITVS or any other entity." Your response to that, Tia Lessin?

TIA LESSIN: I have no doubt that NET, you know, saw it—didn’t see it. I mean, I don’t think Koch saw it. That’s how insidious this is. You know, David Koch doesn’t need to pick up the phone and yell at anybody. He just has to tap his wallet, and, you know, our film disappears.

AMY GOODMAN: In fact, he did quit the board. He resigned from WNET just a week or two ago.

TIA LESSIN: That’s right.

AMY GOODMAN: And was a major donor, what, has overall given something like $23 million.

TIA LESSIN: That’s right, tax-deductible dollars, you know? And in exchange for that, apparently he has some role in programming decisions over at NET, and I think that’s really unacceptable.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: So, in essence, what we’re looking at here is not necessarily a direct intervention by Koch, but self-censorship by the public television community in an effort to prevent someone like Koch from pulling their dollars out.

TIA LESSIN: That’s right. That’s right.

CARL DEAL: Yeah, yeah.

TIA LESSIN: Well, and, actually, I think why does somebody like David Koch make such a major contribution to public broadcasting, when in fact he’s against public institutions like public broadcasting? I think it probably has to do with having some influence over what gets said on the public airwaves.

AMY GOODMAN: You were at the protest yesterday here in New York. There were protests around the country around the issue of the Kochs buying newspapers like the Los Angeles Times. What connection do you see here, Carl?

CARL DEAL: Well, look, we didn’t enter into this conversation lightly, but our experience, we feel that our film was censored, and it was due to the presence of David Koch on the board. And there’s a lot of discussion right now over whether or not private ownership of newspapers has an influence on how the news gets reported. And we just feel like our recent experience sheds light on that. If there were ever any doubts, in this case, whether or not David Koch directly intervened, his mere presence had an impact on the public discourse.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to break, and then, when we come back, talk about the content of your film, Citizen Koch. This is Democracy Now! Back in a minute.

ITVS Board Of Directors

http://www.itvs.org/about/board/

Board of Directors

Chair

Garry Denny

Director of Programming

Wisconsin Public Television

Madison, WI

Vice Chair

Bathsheba Malsheen

President and CEO

MiNo Wireless

Santa Clara, CA

Secretary

Malinda Maynor Lowery

Assistant Professor of History

University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill

Chapel Hill, NC

Treasurer

Robb Moss

Lecturer

Harvard University

Cambridge, MA

Executive Committee

Lisa Cortés

President

Cortés Films

New York, NY

Executive Committee

Cheryl Head

Chief Operating Officer

Livingston Associates

Baltimore, MD

Members

Sharese Bullock-Bailey

Producer; Strategic Consultant

Brooklyn, NY

Beth Curley

President and CEO

Nashville Public Television

Nashville, TN

Tracy Fullerton

Associate Professor

USC School of Cinematic Arts

Los Angeles, CA

Ian Inaba

Executive Director

Citizen Engagement Lab

Berkeley, CA

Marie Nelson

Senior Director and Executive Producer

of News and Original Programming

BET Networks

Washington, DC

Jean Tsien

Producer, Editor

Forest Hills, NY

Margaret Wilkerson

Professor Emerita

University of California-Berkeley

Kensington, CA

Read the most recent board of directors meeting minutes

Bay Area Video Coalition Which Manages San Francisco Community College Channel

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Dr. Bathsheba Malsheen, Board President

Dr. Bathsheba Malsheen is BAVC's Board President and has served as CEO of several mobile technology companies. Most recently, she was president and CEO of MINO Wireless, which provided managed global roaming services for mobile operators. Dr. Malsheen was previously CEO at Groove Mobile, the world's leading mobile music service provider and CEO of Voxware, a global provider of mobile voice-based enterprise solutions for distribution and warehouse operations. She currently serves as a Board Member of Independent Television Service (ITVS) and Board Advisor to SoundHound, producing applications in audio and music identification, voice recognition and search technologies. Dr. Malsheen holds a BA from Hofstra University, and an MA and PhD from Brown University in Linguistics.

Neil O’Donnell, Vice President

Neil O’Donnell, BAVC's Board Vice President, is a founding partner of the San Francisco and Washington, D.C. law firm Rogers Joseph O'Donnell where he is co-chair of the government contracts and construction practice groups. He has been consistently named one of the leading government contract lawyers in the country by Chambers USA, America's Leading Lawyers for Business. Neil serves on the Advisory Committee for The Government Contractor and on the Associated General Contractors of California Legal Advisory Committee, and is a member of the ABA’s Section of Public Contract Law and Forum Committee on the Construction Industry. He holds a JD from Yale Law School, and a BA from Williams College.

Jason Kipnis, Board Treasurer

Jason Kipnis, BAVC's Board Treasurer, manages the Intellectual Property (IP) Counseling practice in the Silicon Valley Office of Weil, Gotshal & Manges, and has extensive experience in patent portfolio management, IP litigation and pre-litigation counseling, IP due diligence, and IP transactions. Jason is also an adjunct lecturer at Stanford Law School, where he teaches IP Strategy for High Technology Companies, and is a frequent speaker on intellectual property matters at professional and academic conferences. In addition, he has been selected by the IAM250 as one of the world’s leading IP strategists. Jason holds a JD from Stanford Law School, and an SB and SM from Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Angela Jones

Angela Jones is currently a Program Specialist with Northern California Grantmakers, responsible for developing skill-building workshops to enhance the effectiveness of grantmaking professionals and formerly worked at The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation its Conflict Resolution Program. She holds a BA from the University of California-Berkeley and is pursuing an MBA in Finance and Marketing at Mills College in Oakland. Angela also serves on the advisory board for Chicken & Egg Pictures, a hybrid film fund and non-profit production company dedicated to supporting women filmmakers who are as passionate about the craft of storytelling as they are about the social justice, environmental and human rights issues they are exploring on film.

The BAVC Board of Directors is always seeking interested candidates and suggests that interested members of the community contact info [at] bavc.org with a bio and letter of interest.

With over 100 public and educational channels disappearing since the mid-2000s, we need to have a big rethink about quality public-access TV.The Cable TV Access Crisis

http://www.alternet.org/media/151905/the_cable_tv_access_crisis?page=entire

August 7, 2011 |

Public-access television has always had a low-budget, amateur reputation. Yet Rod Laughridge's alternative news program "Newsroom on Access SF" was anything but that. Though San Francisco's public-access station had its share of offbeat shows —- like the risqué DeeDeeTV, hosted by self-described "pop culture diva" Dee Dee Russell — "Newsroom" took itself seriously. Its mission, as described on its website, was to "bring community-based, community reported and produced independent news and interviews from a grassroots viewpoint — unhindered, uncensored and unaltered."

The show, which ran for five years on Channel 29, followed a professional news format with high production values. Anchors reported headlines from behind a studio desk as video streams played in the background. Local news segments on topics like the plight of renters and live reports from homeless shelters were interspersed with commentary by the likes of Mumia Abu-Jamal and Angela Davis, and international news from Al-Jazeera. During its run, "Newsroom" was nominated for an Emmy and won several Western Access Video Excellence (WAVE) awards. "It was a full-blown news show," Laughridge recalls.

Unfortunately, "Newsroom" became a casualty of a ripple effect brought on by the passage of a bill that slashed the public-access operating budget across California. This resulted in a new provider, the Bay Area Video Coalition (BAVC), which had no prior experience operating public TV, taking over SF's two public-access channels. BAVC closed the production studio where "Newsroom" and other shows were produced and instituted a different model that did away with the traditional three-camera set-up. Laughridge notes that, in the old days, staff members assisted public-access producers with editing. Now "you have to pay for [BAVC's] classes to do that. There's a conflict right there," he says. These changes to the public-access model effectively "killed the idea of community" in community television, Laughridge says.

The loss of an award-winning program like "Newsroom," which provided a viable, community-based alternative to network TV news, symbolizes one of the clearest examples of what has transpired as a result of the public-access crisis. As the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) noted in its 2011 media review, "State and local changes have reduced the funding and, in some cases, the prominence on the cable dial of public, educational and government channels (PEG) at a time when the need for local programming is especially urgent."

The Perils of PEG Centers

The public-access crisis in California was brought about by the 2006 passage of the Digital Infrastructure and Video Competition Act (DIVCA), a bill that was heavily lobbied for by Comcast and AT&T. According to the telecommunications industry, DIVCA was supposed to create jobs, increase competition and serve the public interest. Its actual effect was the exact opposite — cable companies eliminated jobs and ultimately faced less competition from the defunding of community television stations. As of 2009, similar bills had been passed in 25 states, with similar results.

Since the mid-2000s, more than 100 PEG stations across the country have disappeared; cities like San Francisco and Seattle have cut as much as 85 percent of the PEG operations budget. City funding for public access has been entirely eliminated in Denver and Dallas; at least 45 such stations have closed in California since 2006-12 in Los Angeles, the nation's No. 3 media market, alone. As many as 400 PEG stations in Wisconsin, Florida, Missouri, Iowa, Georgia and Ohio are facing extinction as well.

Moreover, according to a 2010 study by the Benton Foundation, these cuts have disproportionately affected minority communities. Adding insult to injury, AT&T and other cable providers have employed what's known as "channel-slamming": listing all public-access channels on a single channel or making them accessible only in submenus, which makes finding them difficult for viewers.

A bill currently before the House of Representatives called the Community Access Preservation, or CAP, Act, could prevent hundreds of funding-challenged PEG stations nationwide from going belly up. The bill limits channel-slamming and would amend an FCC ruling that PEG support may be used only for facilities and equipment, and not for operating expenses. Even if the CAP Act passes, it "won't solve all of public-access TV's problems," says Media Alliance executive director Tracy Rosenberg. For one thing, the CAP Act falls short of mandating a higher percentage of cable franchise fees — an estimated $10 million to $12 million in SF — for PEG operators. Increasing this revenue, however, could allow PEG stations not only to survive, but to thrive.

An Open-Source Solution?

One possible solution for financially challenged PEG stations is the development of open-source or user-modifiable software — a model currently being developed in Denver, San Francisco and several other cities. In just its second year of operating SF Commons — SF's public-access station — BAVC is already attracting wider attention. In June 2011, the organization was singled out for praise by the FCC, which called SF Commons one of the "most promising templates for the future of public-access centers."

Open source offers built-in internet connectivity and is less financially constraining than the old public-access model, requiring less equipment and less staff. Instead of reels of videotape or DVDs, programs are saved as MPEG files. Editing workstations aren't bulky analog machines but svelte Macintosh computers equipped with Final Cut Pro editing software.

Yet open source isn't a perfect solution. In the short-term, moving to an open-source model for public access may actually widen the gap affecting underserved and less technologically literate demographics. "Seniors, disabled, low-income adults," Rosenberg charges, "[are] being left off the train."

Adapting open source to a public-access medium also limits the potential of users to acquire skills needed for some television jobs and puts more emphasis on offsite production, which in turn reduces the level of interaction between programmers. "They want you to edit at home," Laughridge says. "There's the digital divide right there: Not everyone has a computer or camera."

Virtual Community vs. Actual Community

Laughridge is one of several veteran public-access programmers who complain about displacement under BAVC.

Ellison Horne, a former president of Channel 29's Community Advisory Board (CAB), says BAVC made an "aggressive move toward a virtual studio as opposed to what we had before, which was a community media center." This resulted, he says, in a lack of community engagement.

Since BAVC's takeover of Channel 29, "a very different culture has emerged" in San Francisco public access, says documentary filmmaker Kevin Epps, who began his career in public access. That culture is more conservative, tech-savvy, youth-oriented and, in Horne's words, "elitist."

Steve Zeltzer, a labor activist and public-access producer, charges the BAVC takeover has resulted in "the privatization of public access."

Ken Johnson, who worked for a stint as a producer-director at local station KQED after getting his start on Channel 29, credits public-access TV with helping him stay off the streets and out of jail. Johnson says he often rounded up street people as volunteers to help him produce his show on veterans' issues. But volunteers are no longer welcome under BAVC's operatorship.

Instead of a community-supportive environment, Johnson says, "They have this robotic thing when you do it like that, you lose something."

BAVC staff are quick to characterize the problems with public-access programmers as simply a case of the old guard being resistant to change. "You had a lot of producers used to doing the same routine for X amount of years," says Andy Kawanami, SF Commons' community manager. He concedes the transition to open source wasn't completely smooth, but says things "have settled down quite a bit" since.

Former BAVC executive director Ken Ikeda has been quoted as saying, "We've learned the hard way what innovation in isolation can cost an organization." And Jen Gilomen, BAVC's director of public Media Strategies, admits "we've lost some people" in the transition. However, she says, the economic reality means "the whole model had to change."

Making Open Source Work for Everybody

A considerable learning curve is involved in adapting open source to public-access television, says Tony Shawcross, Executive Director of Denver Open Media (DOM). After taking over Denver's PEG channel in 2005, DOM underwent a period of trial-and-error, discovering what worked and what didn't. In 2008, DOM received a $400,000 Knight Foundation grant which allowed it to revise its model to make it more community- and user-friendly.

"We had to go through that process in order to learn what it took to make the tools work for others," he says. Overall, Shawcross says DOM isn't reaching as wide a constituency as its predecessor, but, he adds, "You can't just talk about diversity and our model without also talking about money. Dollar-for-dollar, I'd say DOM is doing better in reaching disadvantaged communities, but we'd be doing much better if we had $500,000 annually to invest in serving the communities who are most in need."

BAVC, Shawcross says, is "one of the few success stories in public access." However, he says, BAVC "are very focused on their own needs, and the development work they're doing in open source is not focused on benefitting the rest of the community as much as it would if that were a true priority for them."

BAVC is "one of the few success stories in public access," Shawcross says, but it's "very focused on their own needs, and the development work they're doing in open source is not focused on benefiting the rest of the community as much as it would if that were a true priority for them."

Currently, BAVC has no initiatives "specific to diversity," says Gilomen. Yet BAVC has made forays into community outreach via the Neighborhood News Network (n3), three partnership pilot programs with nonprofit centers utilizing these centers' media production facilities. Ultimately, the FCC notes, n3 "will link PEG channels to 15 community sites throughout the city, using an existing fiber network." After airing on SF Commons, these programs will be accessible to viewers as one of BAVC's online channels.

Although they've made for good PR copy on BAVC's website, the three n3 programs have thus far resulted in a total of just 77 minutes of actual on-air programming. "We need more money to expand these programs," Gilomen says, which she hopes "will seed news bureaus."

With a single-camera studio set-up, n3's no-frills production values lag behind the standard set by "Newsroom." At times, the content resembles infomercials for BAVC's community partner organizations. In the Mission District's n3 pilot episode, anchor Naya Buric, a BAVC intern, repeatedly stumbles over her words, at one point misidentifying n3 as "neighborhood network news." When asked what difference n3 will make to the community, guest Jean Morris touts the Mission Cultural Center for Latino Arts' programming, yet fails to mention any issues of substance affecting the neighborhood, such as gentrification and gang violence. The Bayview-Hunters Point pilot show, meanwhile, features members of the Boys and Girls Club, aged 9-12, covering the club's own Junior Giants program. The South of Market pilot fares a little better, with segments on redevelopment, a fire at a single-room occupancy hotel and the availability of bathrooms for SF's homeless population. It remains to be seen whether n3 programs can fill the role "Newsroom" used to play, much less consistently cover topics of serious concern to neighborhood residents. Willie Ratcliffe, publisher of independent African-American newspaper SF BayView, recognizes the n3 program in Bayview-Hunters Point as a positive development for a handful of young people. However, he says, "I don't see where it's gonna do too much" to address the "burning issue [of] economic survival," nor the police brutality, health issues and environmental concerns Bayview residents face daily. In his view, the smiling African-American faces pictured on BAVC's website are "just being used, really," he says.

The Hope of Digital Integration

Two years after launching SF Commons, the station is still very much a work in progress. The lack of a consistent program schedule, some producers say, makes it difficult to build a regular audience. But Gilomen says this concern will be addressed in the coming months as BAVC rolls out a new set of web-based tools allowing producers to self-schedule their programs and archive content online. Besides eliminating the need for physical DVDs, this makes it possible for public-access stations in other markets to air SF Commons' content.

However, the true test of BAVC's public-access stewardship is yet to come. SF Commons features prominently in a SF Department of Technology (SFDOT) broadband inclusion initiative, which, if successful, could form the 21st century model for public access in America.

In addition to the operating budget of $170,000 for two PEG channels from SFDOT, BAVC is also the recipient of $2 million in technology grants specifically tied to broadband initiatives aimed at increasing digital literacy. But while the potential for using digitally integrated public-access and broadband services to close the digital divide exists on paper, these services haven't been implemented in a concrete, tangible way — with measurable results — yet.

SFDOT policy analyst Brian Roberts uses buzzwords like "digital inclusion" and "affordable access" in describing the city's B-TOP program, which envisions the creation of a "public broadband space" (PBS) incorporating public access as one of its components. The idea of a PBS is "having access to training and technology people couldn't afford in their homes," Roberts explains. But, he says, "we're not sure where that's going to go."

The B-TOP program relies on federal grants and matching funds for its S10 million budget. So far it's created a handful of new bureaucratic positions, doled out tens of thousands of dollars to BAVC for equipment purchases, started a digital media skills training course at City College of San Francisco and held several community outreach events. Yet it's had little to no impact on improving access in SF's most technologically underserved neighborhoods, which is what it's supposed to do. According to SFDOT's most recent report on sustainable broadband adoption, the program is only 1 percent complete at this time. SFDOT has failed to meet its baseline goals for new subscribers receiving discounted broadband service; currently there are "zero" households and "zero" businesses participating, which it blames on "implementation delays."

In other words, despite the FCC's flowery praise for BAVC and SFDOT's collaborative efforts, the vision of a fiber-optic network broadcasting hyperlocalized content over public-access airwaves isn't crystal clear.

An Upside Down Model?

While SFDOT and BAVC wait for the sustainable broadband initiative to take shape, a cadre of veteran video producers are attempting to fashion their own template for public access's immediate future.

Instead of relying on technology grants based around not-quite-there-yet initiatives, this model would pool the existing resources of several cities in Contra Costa County, each of whom receive PEG funding from cable operators, to create a countywide community media center. Instead of just under $200,000 in operating expenses, the center's budget could be closer to $2 million, enough to run a top-notch PEG center with high-quality production values. This center would be run not by outside operators, but by the producers themselves, fulfilling one of the FCC's recommendations for high-performing PEGS: "the ceding of editorial control to producers."

Could a super-PEG center serving the needs of an entire county, rather than an aggregation of smaller PEGS tied to specific cities, be a way to ensure the future of public access while preserving its vibrant culture?

Sam Gold, the man behind the effort, thinks so. He's assembled a team consisting of several former SF public-access producers and is actively pursuing getting the necessary approval from various city councils. He calls the effort "an upside down model," since he's invested $40,000 of his own money into equipment. In his mind, they key question is to whether the center can be established on public space, which would alleviate the biggest operating cost, that of renting a facility. If successful, Gold's model could be replicated in other markets, offering a third option to the public-access crisis besides ceasing operations or acquiescing to the imperfections of open source. "Wonder if we can get the old 'Newsroom' crew back together?" Gold ponders during a lunch with Laughridge and several other public-access veterans. Laughridge just looks at him and smiles.

Eric K. Arnold wrote this story as part of a series produced by the G.W. Williams Center for Independent Journalism for a media policy fellowship sponsored by The Media Consortium

For more information:

http://www.democracynow.org/2013/5/30/did_...

We are 100% volunteer and depend on your participation to sustain our efforts!

Get Involved

If you'd like to help with maintaining or developing the website, contact us.

Publish

Publish your stories and upcoming events on Indybay.

Topics

More

Search Indybay's Archives

Advanced Search

►

▼

IMC Network