From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

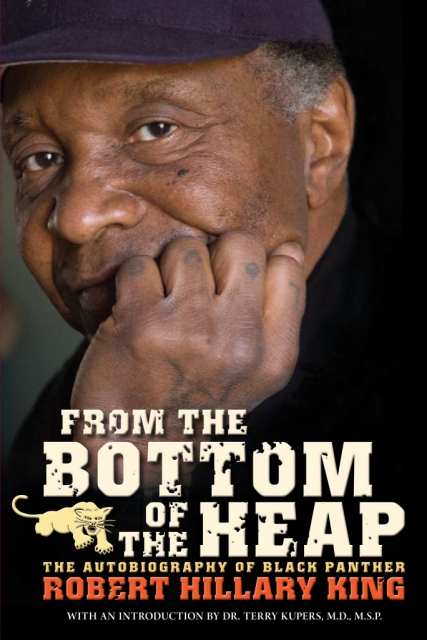

From the Bottom of the Heap: Review of the Autobiography of Robert Hillary King

Robert Hillary King begins his autobiography, From the Bottom of the Heap (PM Press, 2009), with these words: “I was born in the U.S.A., born Black, born poor. Is it any wonder then, that I have spent most of my life in prison?”

The original Spanish language version follows the English version below and is available here: http://www.noticiasdelarebelion.info/?p=5059

From the Bottom of the Heap: Review of the Autobiography of Robert Hillary King, Black Panther and ex political prisoner of the Angola 3

by Carolina Saldaña

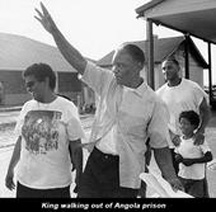

At 4:12 in the afternoon of February 8, 2001, prisoners and supporters cheered as Robert Hillary King* walked out of the infamous Angola penitentiary where he was locked up for more than thirty-one years. Since then, he hasn’t stopped working to free Albert Woodfox and Herman Wallace; together, they’re known as the Angola 3. In the early ‘70s, these Black Panthers organized other prisoners to resist degradation, violence, and death in “the bloodiest prison in the United States,” widely known as a modern slave plantation in the state of Louisiana. Convinced that they’d do so again, given the opportunity, the prison authorities have opted to keep them in isolation for decades. King spent twenty-nine years in solitary and, as of now, Woodfox and Wallace have lived in these conditions of torture for more than thirty-seven years.

King begins his autobiography, From the Bottom of the Heap (PM Press, 2009), with these words: “I was born in the U.S.A., born Black, born poor. Is it any wonder then, that I have spent most of my life in prison?” He tells his story in a clear, direct style, with a lot of details and reflections that let us know he’s also talking about the daily experience of millions of his contemporaries.

He’s grateful to his biological mother for leaving him with his grandmother, who loved him like she did her other nine sons and daughters. To him, she was Mama, the one who took care of him even though she “worked the sugar cane fields from sun up ‘til sun down for less than a dollar a day. During the off season, she washed, ironed clothes, and scrubbed floors for whites” in the small town of Gonzales, Louisiana, for pennies a day or for leftovers.

He remembers that when he was four years old, he and Mama stopped by the town jail, where a distant cousin of his worked as jailer. When the man offered him something to eat he just stared at him. He didn’t want any of that food. He noticed another Black man in the corner, behind a lot of “skinny iron” and felt a kinship with him. Mama called the man a “cornvick” and said he was probably there because he’d done something bad. As he tried to figure this out, Robert thought of the corn fields all around the town and reasoned that the man probably lived there among the cornstalks and “was considered bad for doing so.”

He cried when one of his relatives executed a dog he loved named Ring, a smart German Shepherd that was good at “finding” things ––even “shoes in pairs”! But one day Ring bit his brother James. He was slobbering and had a “fierce glare in his eyes.” King says it was commonly believed he had “gone mad,” but remembers that he looked remorseful and apologized with his eyes before he was shot through the head.

In 1947, the family moved to Algiers, that part of New Orleans on the other side of the ”muddy Mississippi River.” There, little Robert met Mule, who cared about Mama and helped her support the family, working hard when there was work to be had. He livened up his days with a little Muscatel and cheered up Robert with his sense of humor and affection. Says King: “I colored him father.”

Robert also got to know the streets of New Orleans and learned how to fight so as to survive and make friends there. Around that time, his family learned that two of his older brothers, Houston and Henry, were in prison in other cities, news that deeply saddened Mama.

When he was thirteen years old, Robert met his natural father, Hillary, and went to live with him and his wife Babs in the town of Donaldson for a couple of years. They didn’t treat him well, and his dad often hit him. He did do well in school though, and as he walked by the town’s juke joints was lucky enough to hear the sounds of Big Joe Turner, Chuck Willis, Big Mama Thornton, Ruth Brown, Jackie Wilson and many more, but his favorite was Sam Cooke. Robert finally headed back to New Orleans, leaving Hillary and Babs $50 (that he had stolen) and a note telling them that the sum should “more than cover the amount of kindness you’ve given me.”

When he couldn’t find work in Algiers, King decided to go north, to Chicaco, with dreams of making thousands of dollars to send back home to Mama. On his way out of the city, he met two white hobos, an encounter that wasn’t all that common in a South defined by apartheid. But he got lucky. They said he could tag along and shared their pocketful of nothing with him. In Chicago though, doors closed in his face and Robert got tired of sleeping on icy streets. He headed back home with the help or another hobo, but not before a YMCA director tricked him into spending three weeks in a detention center. When he got back, his feet hurt so bad he couldn’t walk. Mama’s diagnosis was frostbite, which she cured with hot rutabaga poultices.

In 1958, his compassionate sister Ruth died as a result of a botched abortion she felt compelled to have because before she could get on welfare, she had to promise not to have any more children. That was department policy for decades. Shortly thereafter, Mama went to the hospital, and the family found out she had cancer. After several treatments, they sent her home to die.

When Robert was fifteen, he was arrested because he fit the description of somebody who had robbed a gas station. He was sent to the Scotlandville Reformatory. Given the situation, he felt like things weren’t so bad. In fact, he couldn’t believe his luck to find that there were girls in the same institution! Falling in love with Cat put him in violation of a street code that prohibited a girl from going with someone new as long as her ex boyfriend was still in the reformatory. A boy could do it, but a girl couldn’t. This didn’t seem right to Robert, who kept up the romance. The ex boyfriend by the name of Pug had a reputation for being good at boxing and wanted to settle the matter in the ring. King says: “…his mechanized, predictable moves were no match for my undisciplined street style….He was admitted to the infirmary for three days. When he returned to the dormitory, he kindly gave me his blessing to continue my relationship with Cat. The code was broken. We became sort of friends.”

From that time on, things went from bad to worse for King as far as his problems with the law were concerned. A hundred years before, when the southern states replaced the “Slave Codes” with “Black Codes” to restrict the freedom of the Black population, vagrancy laws proliferated. When Robert was a teen-ager, an ordinance was still in effect that required males old enough to work to show “visible means of support.” Anyone who didn’t have a check stub or other proof could be jailed for seventy-two hours. “The 72” was especially applied to young Black men, and King went to jail on it several times, even when he did have proof of income.

One afternoon in 1961, Robert was riding around town in an old jalopy with some of his Scotlandville friends when they were arrested on suspicion of robbery by the same cop who had sent him to reform school. His three friends were identified by their victims, but since nobody identified Robert, the authorities decided that he had driven the getaway car. King says, “This theory could have been easily disproven had I been able to afford an attorney, because at the time I didn’t know beans about driving…”

Even so, he was sent to Angola Prison at the age of eighteen for the first of three times. When the twelve prisoners chained together, all Black, got out of the van, Robert felt like he “had been hurled backwards, into the past.” The way the guards talked, walked, and treated the prisoners was like something out of “a former period.” There were also a lot of prisoners who functioned as guards; they shared the guards’ contempt for the prisoners and beat them and chased them zealously when they tried to escape. In those days, around 4,000 prisoners worked on the 18,000 acre plantation for two and a half cents an hour. Two thirds of them were Black, but hardly any had office jobs; those were reserved for the white prisoners.

Angola began as a slave plantation in the middle of the nineteenth century. It was one of many southern plantations converted into prisons after the Civil War, a maneuver that allowed the dominant class to keep on profiting from the unpaid work of Black men. Today, 5,000 prisoners, 80% Black, work the same lands for between two and four cents an hour.

When Robert walked into the Angola dormitory, he was pleasantly surprised to find his uncle Henry there. He hadn’t seen him for six years. In what the young man saw as a “war zone,” where the prisoners were trapped in a disastrous pattern of “fratricide,” “suicide and self-destruction,” his uncle helped him calm down to be able to survive. At Angola, Robert learned all the tasks of growing, harvesting, and processing sugar cane. His uncle trained him in boxing and a friend named Cap Pistol taught him how to make pecan candy --pralines.

When Robert was paroled in November of 1965, at the age of twenty-two, he felt like leaving the prison alive was an accomplishment. He worked as a boxer for a few months, got married, and was about to be a father when he was entrapped in a police dragnet. His parole was revoked and he was sent back to Angola, where he worked in the fields and in the kitchen. He got to know his son in the visiting room. He no longer viewed his imprisonment as “being decreed,” as he had before; he knew who had sent him there, but he still didn’t know why.

When he was released in January of ’69, he felt like the situation in Angola was worse than it was in ’61 ––more murders, more economic slavery, more sexual slavery. But at the same time, a dramatic change had taken place in the country, and a new “Black Consciousness” was strong in New Orleans. Robert identified with this and loved to say “I’m Black and I’m Proud.” He didn’t want his young son to go through everything he’d gone through and worked hard to support him. He loved to spend time with him.

In February of 1970, at the age of twenty-eight, King was charged with a robbery committed by Wortham Jones and a forty-year-old man.” Jones named King as his accomplice, but passionately retracted his testimony during the trial, accusing the police of torturing him. It was too late. There wasn’t a shred of evidence against King, but the district attorney convinced his friends on the jury to find him guilty and sentence him to thirty-five years. It was hard for King not to stay “killing mad” with Jones, but he finally decided that the best thing to do was turn his anger against the system.

King now saw all the appeals presented by his lawyer as a mere formality. He decided to file a different kind of appeal, and along with twenty other prisoners who “also felt this need to appeal to no one but themselves,” made a break for freedom. He says that even though the plan for getting out was good, they didn’t consider the details of making themselves “invisible” once they were outside. Only three men avoided immediate capture. A few hours later, one was shot and killed, another negotiated his surrender, and only King was able to stay “invisible” for two weeks before being reported. The escape cost him a sentence of eight additional years.

King had been aware of the tremendous transformation going on in the country, especially with regards to African-Americans, but his definitive “awakening” took place when he found out that the Black Panther Party was right there in New Orleans. This happened one day when he was watching television and saw the unprecedented shootout between the police and a group of Black men and women on Desire Street in the Ninth Ward. It wasn’t long before he met them personally in the New Orleans Parish Prison.

He remembers a Panther named Cathy, who “was a source of strength to many of the prisoners” and his “greatest inspiration.” In his conversations with Ron Ailsworth, he came to understand the colonial plight of Black people as well as the dire situation of other poor people in the United States. They also talked about collectivity and “means and methods of struggle.” His introduction to the Black Panthers wasn’t limited to words. In order to make changes in the horrible prison conditions, which included a plague of huge rats and sewer water that flooded the halls where the prisoners slept on the floor, the Panthers in one part of the jail took two guards hostage, while in his section, King participated in a hunger strike with hundreds of other prisoners. Despite reprisals, they were able to call public attention to the conditions.

To King, the Black Panther ideology “defined the overall Black experience in America –– past and current” and offered alternative ways of resisting repression “politically, economically, racially, and /or socially by any means necessary,” in the tradition of Malcolm X. The struggle was seen from the perspective of downtrodden people and the goal was for “the people to be their own vanguard.” The organization wanted freedom, justice, land, bread, education, housing, and an end to police brutality and to the occupation of the Black communities. King agreed with the idea of nationalism, that is to say, with the struggle of the African-American people, and also with internationalism. It seemed logical to him that the necessary changes would only come through revolution.

It was in the New Orleans jail that King received the tragic news that his son had a brain tumor. Shortly thereafter, little Robert died at the age of five, leaving his father in tears, devastated, but with a renewed commitment to understand absolutely everything.

“In studying and learning of my enemy, I also learned of myself, my place in history….I saw that all are expendable at the system’s whim. I saw how my mother, her mother, and her mother’s mother before her suffered. I saw past generations of my forefathers stripped from their homeland, brought, by force, to these shores in chains. They were stripped of all sense of responsibility; their only obligation belonged to their servitude. I saw mothers become the predominant parental figure within the slave unit, while fathers did not know their own offspring. I was able to put some of my father Hillary’s actions into perspective. Hillary, born into a white world and dominated at every turn, felt the need himself to dominate.”

In 1971, King was transferred to Angola again. That same year, Albert Woodfox, Herman Wallace, and Ron Ailsworth, among others affiliated with the Black Panthers, had arrived and established a chapter of the party inside the prison. King got there just after a white guard named Brent Miller had been killed. For days, the entire prison was shut down. There were no visits. There were mass punishments against the Black prisoners. King was sent to a dungeon along with hundreds of other prisoners “under investigation.” They were savagely beaten, forced to run the gauntlet, stripped, and thrown into cold, bare cells. King and several others were found “guilty of wanting to play lawyer” and sent to the death house, where they experienced starvation.

Afterwards, King was isolated in the Closed Cell Restriction (CCR) area. In this seven-story unit, the prisoners were locked in their cells twenty-three hours a day, seven days a week. For years, they couldn’t go out to the yard. They could only leave their cells an hour every day to shower. On June 10, 1973, a prisoner was killed, and the eleven prisoners who happened to be out of their cells were charged with murder. Only King and Grady Brewer were found guilty based on the false testimony of two “surprise witnesses” who had been bribed. They were tried in chains with their mouths taped shut; both received life sentences.

At his time, Albert Woodfox and Heman Wallace faced charges for the murder of Brent Miller, even though they weren’t anywhere near the place where the guard was killed. Even so, they were tried and condemned for his death as a punishment for being Black Panthers. The state’s attorney relied on the false testimony of a known snitch Hezekiah Brown in the case of Woodfox, and the cooperation of Chester Jackson in the case of Wallace. King says that the court ignored the testimony of a prisoner who was mopping the floor on the morning of the murder; he testified that they only person near the scene of the crime was “a white boy.” King also mentions the “evidence” from the prison grapevine that it was Assistant Warden Hayden Dees himself who “did the unthinkable and ordered the ‘hit’ on Miller” because of his resentment at not having been named Warden. Robert says, “If true, Dees, being the racist that he was, would never have sent a Black prisoner to murder a white prison guard.”

In 1973, King volunteered to move to the “Panther Tier” to be with Woodfox and Wallace. Once there, he warned them that there was a plan to break the unity of the Panthers on the tier by sending them to different places. They made preparations and waged an all-night battle before the guards were finally able to move Woodfox and Wallace off the tier.

At times, from 1974 to 1978, when the Panthers were on the same tier, they used the hour when they were outside their cells to talk, share reading materials, and organize protests. They were able to make some changes. They put an end to the practice of having to slide their food trays under the filthy bars and forced the prison to limit the denigrating rectal searches. They made a decision to resist the searches. “We would not be willing participants in our own degradation.” They knew there would be serious consequences and that they would be separated, so they exchanged addresses and telephone numbers of relatives outside the prison. King says that they took him in chains to an office where there were rows of guards with bats, billy clubs, and other arms. “I was told to turn around and bend over. Naturally, I refused…We fought. Finally I was subdued by sheer force of numbers.” They took him to the new punishment unit, Camp J, and charged him with assaulting the officers. But “no anal examination occurred that night.” Woodfox called King’s relatives, who in turn, called the prison. “This gesture saved me from additional injuries, and perhaps death as well.” The prisoners then won a civil suit that prohibited “routine anal searches.” King says that these searches now only occur when “ ’warranted,’ whatever that means.”

King spent two years in Camp J, where the physical and psychological torture of the prisoners went unchecked. He says, “I was told by officials at that camp that what they were doing was condoned by persons in high places.” He reports that a special psychiatric unit was built at the prison, mainly for the victims of the atrocities committed at Camp J.

With regards to the terror that he experienced during his years of isolation, King says that without the appraisal of the Black Panther Party, he “could not have survived intact those twenty-nine years…this truth has sustained me.” He explains that the party’s slogan “Power to the people” comes from the concept that “power actually does belong to the people” but that people “have relinquished that power to a small faction of people called politicians” and in so doing, have left themselves “at the mercy of ever-changing restrictions defined as laws .”

For King, it is primordial to recognize prison as an extension of slavery. Supposedly abolished by the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, slavery is permitted for “people duly convicted of a crime.” He comments that “Mumia Abu-Jamal is in prison because slavery was never abolished,” as well as Jalil Al Amin, the San Francisco 8, Herman Wallace, Albert Woodfox, and Leonard Peltier. “So let’s call the prisons excatly what they are: an extenuation of slavery. And we must let the politicians know that we know this,” says King. “We the people are our own greatest resource.”

In 1988, the prisoner who had testified against King in his trial repented for having collaborated with the State. He wanted to make a public statement that he had lied. He gave King an affidavit to this effect, and shortly thereafter, another prisoner also retracted, opening a new avenue of appeals.

King says that in 1998, thanks to former Panther Malik Rahim of New Orleans, a movement mainly made up of anarchists and ex Panthers began organizing community support for the Angola Three, an effort that also attracted international support and helped win his freedom in 2001.

Since he got out of prison, King makes his living selling pecan candy that he calls “freelines.” But his real work is winning freedom for his two comrades and putting an end to the torture and slavery in the largest prison in the country, a prison that’s not an aberration, but the prototype of the modern prison industrial complex in the United States –Angola.

Says King: “I may be free of Angola, but Angola will never be free of me.”

--------------------------------------

*Also known as Robert King Wilkerson

For news on the appeals of Herman Wallace and Albert Woodfox, the suit against “cruel and unusual punishment” filed by the Angola 3, the premier of a new documentary about the case, the prisoners’ own writings, and news of the movement in their support, see: http://angola3news.blogspot.com/

To buy the book, contact: http://www.pmpress.org

SPANISH LANGUAGE VERSION:

Desde lo más bajo del montón: reseña de la autobiografía de Robert Hillary King,

x Carolina Saldaña

"Soy libre de Angola, pero Angola nunca será libre de mí", dijo el ex Pantera Negra y ex-preso político de "los 3 de Angola" al salir de la notoria plantación de esclavos en Luisiana en 2001.

A las 4:12 de la tarde el 8 de febrero de 2001, los presos igual que los familiares y simpatizantes de Robert Hillary King, también conocido como Robert King Wilkerson, gritaron su apoyo cuando él salió del infame penitenciario de Angola después de estar encerrado ahí durante más de 31 años. Desde entonces, no ha dejado de trabajar por la libertad de sus compañeros Albert Woodfox y Herman Wallace; juntos, se conocen como “los 3 de Angola”. A principios de los años ’70, estos Panteras Negras organizaron a los demás presos a resistir la degradación, violencia y muerte en “la prisión más sangrienta de Estados Unidos”, ampliamente reconocida como una moderna plantación de esclavos en el estado de Luisiana. Convencidas de que lo harían de nuevo, dada la oportunidad, las autoridades han optado por mantenerlos aislados durante décadas. King pasó 29 años solo, y hasta la fecha, Woodfox y Wallace han vivido más de 37 años en estas condiciones de tortura.

King empieza su autobiografía, Desde lo más bajo del montón (PM Press, 2009), con estas palabras: “Nací en Estados Unidos. Nací negro y pobre. ¿Es de extrañar, entonces, que he pasado la gran parte de mi vida en prisión?” Cuenta su historia personal de manera directa y sencilla, con muchos detalles y reflexiones que nos dejan saber que también está contando la experiencia diaria de millones de sus contemporáneos.

Agradece a su mamá biológica haberlo dejado con su abuela, quien lo amaba igual que sus otros nueve hijos e hijas. Para él, ella era Mama, la que los cuidaba aunque “trabajaba en los campos de caña del amanecer al atardecer por menos de un dólar diario y en temporada baja lavaba, planchaba y limpiaba el piso para los blancos” del pueblo de Gonzales, Luisiana, “por unos centavillos o por las sobras de la mesa”.

Se acuerda que cuando tenía cuatro años, pasaba con Mama por la cárcel del pueblo, donde un primo lejano trabajaba como custodio. Cuando el hombre le ofrecía comida, nada más le miró fijamente. No quería nada de esa comida. Se fijó en otro hombre negro en un rincón, tras mucho “hierro flaco” y sentía una afinidad con él. Dijo Mama que el hombre era un “cornvicto” y que ha de haber hecho algo mal para estar ahí. Al buscar el por qué, el niño se acordó de que hubo muchas milpas de maíz (corn en inglés) alrededor del pueblo y razonó que el hombre probablemente vivía ahí entre las plantas y “fue considerado malo por hacerlo”.

Lloró cuando uno de sus parientes ejecutó a su querido perro Ring, un pastor alemán muy inteligente que “encontraba” cosas ––“¡hasta zapatos en pares!” Pero un día Ring mordió a su hermano James. Estaba babeando y tuvo “una mirada feroz en sus ojos”. Se consideró que “se había vuelto loco” pero al reflexionar después, King recuerda que tenía remordimiento y que pidió disculpas con los ojos antes de recibir un disparo.

En 1947, la familia cambió de casa y de ciudad, llegando a Algiers, la parte de Nueva Orleans al otro lado del “lodoso Río Misisipi”. Ahí el pequeño Robert conoció a Mule, quien quería a Mama y se responsabilizó de ayudarle a mantener la familia, trabajando duro cuando había trabajo. Amenizó sus días con un poco de Muscatel, y los días de Robert con su buen sentido de humor y su cariño. Dice King: “Lo pinté padre”.

Robert también empezó a conocer las calles de Nueva Orleans y aprendió a pelear para sobrevivir y convivir ahí. En estos años la familia supo que dos de los hermanos mayores, Houston y Henry, estaban en prisión en otras ciudades, algo que a Mama le causó gran tristeza.

A la edad de 13, conoció a su padre natural, Hillary, y se fue a vivir con él y su esposa Babs en el pueblo de Donaldson durante un par de años. No lo trataban bien y su papá le pegó con frecuencia. Por otro lado, le iba bien en la escuela y al pasar por los antros del pueblo, tuvo la fortuna de conocer los sonidos de Big Joe Turner, Chuck Willis, Big Mama Thornton, Ruth Brown, Jackie Wilson y muchos otros, pero su cantante favorito era Sam Cooke. Por fin Robert regresó a Nueva Orleans, dejándoles a Hillary y Babs $50 (que había robado) y una nota diciendo que esta cantidad de dinero “debe ser más que suficiente para cubrir todo el cariño que ustedes me han mostrado”.

Al no encontrar trabajo en Algiers, tomó la decisión de ir al Norte—a Chicago–, con sueños de ganar miles de dólares para enviar a Mama. En camino conoció a dos vagabundos blancos, un encuentro poco usual en el mundo de apartheid del Sur de Estados Unidos. Corrió suerte. Ellos permitieron que los acompañara y compartieron la nada que tenían con él. Pero en Chicago también las puertas le estaban cerradas, y Robert se cansó de dormir en calles cubiertas de hielo. Regresó a casa con la ayuda de otro vagabundo, pero no antes de que un oficial de la YMCA le tendiera una trampa, haciéndolo pasar tres semanas en un centro de detención. Al regresar, sus pies le dolían tanto que no pudo caminar. Según el diagnóstico de Mama, fue un caso de congelación, y ella le curó con cataplasmas de nabo sueco.

En 1958, su hermana compasiva Ruth murió en un aborto mal hecho que ella se sintió obligada a pedir porque para recibir la asistencia social que necesitaba, tenía que prometer no tener más hijos. Ésta fue la política del Departamento de Servicio Social durante décadas. Un poco después, Mama se fue al hospital y la familia supo que ella tenía cáncer. Después de varias visitas la enviaron a casa a morir.

Cuando tenía 15 años, Robert fue detenido porque cuadraba con la descripción de alguien que había robado una gasolinera. Lo enviaron al reformatorio de Scotlandville. Sintió que dentro de lo que cabía, no le fue tan mal. De hecho, no pudo creer su suerte al encontrar que ¡hubo chicas en la misma institución! Al enamorarse de Cat, se encontró en violación de un código callejero que prohibía a una chica andar con alguien mientras su ex novio todavía estaba en el reformatorio. Un chavo podía hacerlo, pero una chava, no. Esto no le pareció bien a Robert, quien siguió con el romance. El otro, que se llamaba Pug, tenía fama de boxeador y quería arreglar el asunto en el ring. Dice King: “Sus movimientos mecanizados y predecibles no estaban al nivel de mi estilo callejero.…Él se fue al hospital durante tres días y cuando salió, muy amablemente me dio su bendición para seguir mi relación con Cat. Se rompió el código. Éramos amigos, más o menos.”

De ahí en adelante, las cosas fueron de mal en peor para King con respecto a sus problemas con la ley. Unos cien años atrás, cuando los estados sureños reemplazaron sus “códigos de esclavitud” con “los códigos negros” para restringir la libertad de la población negra, las leyes contra la vagancia proliferaban. Durante la juventud de Robert, todavía estaba en efecto una ordenanza que requería que una persona llevara consigo pruebas de sus medios de apoyo. Si no tenía el requerido boleto o un recibo, podría ser encarcelado durante 72 horas. La ordenanza “72” fue especialmente aplicada contra los jóvenes negros, y a King le tocó la cárcel varias veces, incluso cuando pudo comprobar sus ingresos.

Una tarde en 1961, Robert andaba en una carcacha con unos amigos de Scotlandville, cuando fueron detenidos bajo sospecho de robo por el mismo policía que lo había enviado al reformatorio. Sus tres amigos fueron identificados por las víctimas, pero como nadie señaló a Robert, las autoridades decidieron que él ha de haber manejado el coche en que huyeron. Dice King: “Esta teoría podría haber sido fácilmente rebatida si yo hubiera tenido el dinero para contratar a un abogado, porque yo ni siquiera sabía cómo manejar un coche”.

Sin embargo, el joven de 18 años fue enviado al penitenciario de Angola por la primera de tres veces. Cuando los 12 presos encadenados juntos, todos negros, bajaron de la camioneta y entraron por la puerta de la prisión, Robert sintió que “había sido arrojado para atrás, hacia el pasado”. La manera en que los custodios hablaban, caminaban y trataban a los presos era “de otra época”. También hubo muchos presos que funcionaban como guardias, quienes compartían el mismo desprecio para los presos y los golpeaban y perseguían con ganas si intentaban escapar. En aquel entonces, alrededor de 4,000 presos trabajaban en la plantación de 7,400 hectáreas por dos centavos y medio cada hora. Dos tercios eran negros, de los cuales casi ninguno trabajaba en las oficinas; estos puestos fueron reservados para los presos blancos.

Angola nació como una plantación de esclavos a mediados del siglo diecinueve. Era una de las muchas plantaciones del Sur convertidas en prisiones después de la Guerra Civil, una maniobra que permitió que la clase dominante siguiera sacando ganancias del trabajo no remunerado de los Negros. Hoy en día, 5,000 presos, 80% de los cuales son negros, trabajan las mismas tierras por entre dos y cuatro centavos la hora.

Al entrar en el dormitorio de Angola, fue una grata sorpresa para Robert encontrar ahí a su tío Henry; no lo había visto desde hace seis años. En lo que el joven describe como una “zona de guerra”, donde vio a los presos atrapados en un desastroso patrón de “fratricidio”, “suicidio y auto-destrucción”, su tío le ayudó a calmarse para poder sobrevivir. En Angola, Robert aprendió todos los aspectos de cultivar, cosechar y procesar caña. Su tío le instruyó en el boxeo, y un amigo llamado Cap Pistol le enseñó a hacer pralines ––dulces de azúcar y nuez.

Cuando salió del penitenciario bajo libertad condicional en noviembre de 1965, a la edad de 22, sintió que fue un logro haber salido vivo de ahí. Trabajó en el boxeo unos meses, se casó y estaba para ser papá cuando fue atrapado en una operación encubierta. Su libertad condicional fue revocada, y fue enviado a Angola de nuevo, donde trabajó en el campo y en la cocina. Conoció a su hijo en el cuarto de visitas. Ya no vio su encarcelamiento como su destino, como antes; sabía quién lo había enviado ahí pero aún no sabía por qué.

Cuando salió en enero de ’69 sintió que la situación en Angola era peor que en ’61 –más homicidios, más esclavitud económica, más esclavitud sexual. Pero también había ocurrido un dramático cambio en la ciudad, y el impulso a la “Consciencia Negra” estuvo fuerte en Nueva Orleans. Robert se identificó con esto y le gustaba decir “Soy Negro y soy orgulloso”. No quería que su pequeño hijo sufriera lo que él había sufrido y trabajó duro para mantenerlo. Disfrutó enormemente del tiempo que pasó con él.

En febrero de 1970, a la edad de 28, King fue incriminado por un robo cometido por Wortham Jones y alguien descrito como un señor de 40 años. Jones nombró a King como su cómplice, pero durante el juicio retractó su testimonio de manera enfática, acusando a la policía de torturarlo. Ya era tarde. No hubo una sola prueba contra King, pero el fiscal convenció a sus amigos del jurado a encontrarlo culpable y sentenciarlo a 35 años. Aunque a King le costó trabajo no guardarle “una rabia asesina” a Jones por colaborar en robarle la vida, pasó muchas hora reflexionando sobre sus motivos y su retractación. Por fin tomó la decisión de dirigir esa rabia contra el sistema.

King ya consideraba las apelaciones presentadas por su abogado una mera formalidad. Quería “apelar” de otra manera, y con otros 20 reos que también sentían la necesidad de “apelar sólo a sí mismos”, salió corriendo de la cárcel. Dice que aunque la fuga fue bien planeada, descuidaban los detalles de cómo mantenerse invisibles fuera de los muros. Sólo tres lograron evitar la captura inmediata. Unas horas después, uno de ellos recibió una bala fatal, otro negoció su entrega, y solo King se mantuvo “invisible” durante dos semanas antes de que alguien lo delatara. La fuga le costó una sentencia de ocho años adicionales.

King había estado consciente de la tremenda transformación que estaba ocurriendo en el país, especialmente con respecto a los Africano-americanos, pero su despertar definitorio ocurrió cuando se enteró de la presencia del partido Panteras Negras ahí mismo en Nueva Orleans. Esto ocurrió cuando vio en la tele la balacera sin precedente entre la policía y un grupo de hombres y mujeres negros en la Calle Desire. No tardó mucho en conocerlos personalmente en la cárcel de Nueva Orleans.

Se acuerda de una Pantera que se llamaba Cathy, quien “dio fuerza a muchos de los presos” y “fue la inspiración más grande” para él. En sus pláticas con Ron Ailsworth, llegó a entender la grave situación colonial de los negros y también la situación de otra gente pobre en Estados Unidos. Los dos platicaron también de la colectividad y de los medios y métodos de lucha. El aprendizaje no quedó en palabras. Para lograr un cambio en las horribles condiciones de la cárcel, que incluía grandes ratas y aguas negras que inundaban los pasillos donde los presos dormían en el suelo, los Panteras en una sección de la cárcel retuvieron dos guardias, mientras en su sección, King participó en una huelga de hambre con cientos de presos. A pesar de las represalias, tuvieron éxito en llamar la atención pública a las condiciones.

Para King, la ideología de los Panteras Negras “definió la experiencia pasada y actual de los Negros en América” y ofreció maneras alternativas de resistir la represión “política, económica, racial y socialmente por los medios que fueran necesarios” en la tradición de Malcolm X. Lo importante era trabajar con la gente desde abajo y que “la gente fuera su propia vanguardia”. La organización buscaba “libertad, justicia, tierra, pan, educación, vivienda y un fin a la brutalidad policiaca y la ocupación policial de la comunidad negra”. King estaba de acuerdo con la idea del nacionalismo negro, es decir, con la lucha de su pueblo africano-americano, y, a la vez, con el internacionalismo. Le pareció lógico que los cambios necesarios vendrían a través de una revolución.

Fue en la cárcel de Nueva Orleans que King recibió la trágica noticia que su hijo tenía un tumor cerebral. Un poco después, el pequeño Robert murió a los cinco años, dejando a su papá devastado, llorando, pero con un compromiso renovado de comprender todo.

“Al estudiar y conocer a mi enemigo, también me conocí a mí mismo y mi lugar en la historia…Vi que todos somos prescindibles para el sistema. Vi el sufrimiento de mi mamá y de su mamá y de la mamá de su mamá. Vi como despojaron a mis antepasados de sus tierras y los llevaron aquí en cadenas, por la fuerza. Les quitaron todo sentido de responsabilidad; su única obligación fue a su servidumbre. Vi como la madre se volvió la figura paterna dominante dentro de la unidad esclava mientras el padre no conocía a sus propios hijos. Logré poner en perspectiva algunas de las acciones de mi papá Hillary. Nacido en un mundo blanco y dominado a cada paso, él sintió la necesidad de dominar”.

En 1971, King fue trasladado a Angola de nuevo. El mismo año, Albert Woodfox, Herman Wallace y Ron Ailsworth, entre otros afiliados con el partido Panteras Negras, habían llegado ahí y establecido una agrupación del partido dentro de la prisión. King llegó justo después de que alguien había asesinado a Brent Miller, un guardia blanco. Durante días, la prisión estuvo cerrada. No hubo visitas. Hubo castigos masivos contra los presos negros. King fue enviado a la mazmorra con cientos de otros presos bajo “investigación”; fueron golpeados salvajemente, obligados a correr desnudos entre dos filas de guardias que los azotaron y echados en celdas vacías y frías. A King y a varios otros les encontraron “culpables de fingir de ser abogados” y los enviaron al pabellón de la muerte, donde vivieron condiciones de hambruna.

Después, King fue enviado al aislamiento de la unidad de Celdas Cerradas y Restringidas (CCR). En esta unidad de siete pisos, los presos estaban en sus celdas 23 horas diario, 7 días a la semana. Durante años no pudieron salir al patio. Sólo pudieron salir de sus celdas una hora diario para bañarse. El 10 de junio de 1973, un preso fue asesinado, y los once presos que se encontraban fuera de sus celdas fueron acusados de su muerte. Sólo King y Grady Brewer fueron encontrados culpables debido al testimonio falso de dos “testigos sorpresivos sobornados”. Los dos fueron enjuiciados en cadenas, con cinta que cubría la boca; los sentenciaron a cadena perpetua.

Durante estos años Albert Woodfox y Heman Wallace enfrentaron acusaciones de haber asesinado a Brent Miller aunque ellos no se encontraban remotamente cercanos al lugar donde el guardia fue asesinado. Sin embargo, fueron acusados, enjuiciados y condenados por su muerte como represalia por ser Panteras. El fiscal contaba con el testimonio falso del reconocido soplón Hezekiah Brown en el caso de Woodfox, y con la cooperación de Chester Jackson en el caso de Wallace. Dice King que la corte ignoró el testimonio de un preso que estaba limpiando el piso la mañana del asesinato, quien testificó que la única persona que él vio cerca de la escena fue “un muchacho blanco”. También menciona la “evidencia” que se rumora en la prisión –– que el mismo Subdirector Hayden Dees “hizo lo impensable” y ordenó el asesinato de Miller debido a su rencor por no haber sido nombrado Director. Dice Robert: “Si esto es cierto, Dees, siendo el racista que es, nunca hubiera enviado a un preso negro a asesinar a un guardia blanco”.

En un momento King logró ser transferido al “piso de los Panteras” con Woodfox y Wallace, donde pudo avisarles que hubo un plan para romper la unidad de los presos en el piso y enviar a los Panteras a distintos lugares. Hicieron preparativos y batallaron durante toda la noche antes de que las autoridades por fin lograran sacarlos de ahí.

Desde 1974 hasta 1978, cuando se encontraron en el mismo piso de vez en cuando, usaron su hora fuera de las celdas para comunicarse, compartir materiales de lectura y organizar unas protestas. Tuvieron éxito en lograr unos cambios, incluso el poner fin a la práctica de recibir su comida en la suciedad del suelo debajo de las rejas, y el restringir las denigrantes revisiones rectales. Tomaron la decisión de poner resistencia. “No seríamos participantes voluntarios en nuestra degradación”. Sabían que habría graves consecuencias y que los iban a separar; por eso, intercambiaron direcciones y números de teléfono de parientes fuera de la prisión. Dice King que lo llevaron a una oficina en cadenas donde hubo filas de guardias con bates, toletes y otras armas. “Me negué a doblarme. Peleamos. Por fin me sometieron.” Lo llevaron al Campamento J, el centro de castigo, y lo acusaron de atacar a los oficiales. Pero “esa noche no hubo revisión rectal”. Woodfox llamó a los familiares de King, quienes hablaron por teléfono a la prisión. “Esto me ahorró más lesiones y posiblemente la muerte”. Los presos ganaron una demanda civil en la cual la corte prohibió las “rutinarias revisiones anales”. Dice King que ahora las revisiones sólo ocurren cuando se puedan justificar, “lo que sea que eso signifique”.

King pasó dos años en el Campamento J, donde la tortura física y psicológica de los presos no se frena. Dice: “Fui informado por unos oficiales del campamento que lo que ellos hacían fue aprobado por personas en posiciones de poder”. Reporta que construyeron toda una unidad psiquiátrica en la prisión, principalmente para las víctimas de las atrocidades perpetradas en el Campamento J.

Con respecto al terror que vivió durante sus años en aislamiento, King dice que sin la valoración del partido Panteras Negras, “no pude haber sobrevivido esos 29 años…es la verdad que me ha sostenido”. Explica que la consigna del partido “Todo el poder al pueblo” viene del concepto que “el poder en realidad reside en el pueblo” pero que la gente “ha entregado ese poder a un pequeño grupo llamado políticos” y de esta manera “queda a la merced de las siempre cambiantes restricciones definidas como leyes”.

Para King, es primordial reconocer la prisión como una perpetuación de la esclavitud. Supuestamente abolida por la Enmienda 13 a la Constitución, la esclavitud está permitida para “personas debidamente condenadas de un crimen”. Menciona que Mumia Abu-Jamal está en prisión porque la esclavitud nunca fue abolida. También Jalil Al Amin, antes H. Rap Brown, los 8 de San Francisco, Herman Wallace y Albert Woodfox. “Hay que reconocer la prisión como esclavitud y dejar que los políticos sepan que nosotros sabemos esto”, dice King. “Nosotros mismos, la gente, somos nuestro mejor recurso”.

En 1988, el preso que había testificado contra King en su juicio se arrepintió de haber colaborado con el Estado. Deseaba declarar públicamente que había mentido. Le dio a King una declaración jurada al efecto y un poco después, otro preso también se retractó, abriendo una nueva avenida de apelaciones.

Dice King que en 1998, gracias al ex Pantera Malik Rahim de Nueva Orleans, un movimiento conformado principalmente de anarquistas y ex Panteras empezó a organizar apoyo comunitario para “los 3 de Angola”, un esfuerzo que también atrajo apoyo internacional y ayudó en lograr su libertad en 2001.

Desde su salida de prisión ese año, King gana la vida haciendo dulces de azúcar y nuez llamados freelines. Pero su verdadero trabajo es ganar la libertad de sus dos compañeros y ayudar a poner fin a la tortura y esclavitud en la prisión más grande del país, una prisión que no es una aberración, sino el prototipo del moderno complejo industrial carcelario en Estados Unidos ––Angola.

Dice King: “Soy libre de Angola, pero Angola nunca será libre de mí”.

--------------------------------------

Vean la película Los 3 de Angola: Los Panteras Negras y la Última Plantación de Esclavos (Angola 3: Black Panthers and the Last Slave Plantation, 2006, Director Jimmy O’Halligan, Productores Scott Crow y Ann Harkness), con narración de Mumia Abu-Jamal, el jueves, 22 de abril en el Auditorio Che Guevara a las 6:00 de la tarde en el marco de las actividades para conmemorar el cumpleaños de Mumia Abu-Jamal.

Para leer noticias sobre las apelaciones de Herman Wallace y Albert Woodfox, la demanda contra “el castigo cruel e inusual” levantada por “los 3 de Angola”, sus propios escritos y noticias del movimiento en su apoyo, vean: http://angola3news.blogspot.com/

Para comprar el libro y la película en inglés: http://www.pmpress.org

From the Bottom of the Heap: Review of the Autobiography of Robert Hillary King, Black Panther and ex political prisoner of the Angola 3

by Carolina Saldaña

At 4:12 in the afternoon of February 8, 2001, prisoners and supporters cheered as Robert Hillary King* walked out of the infamous Angola penitentiary where he was locked up for more than thirty-one years. Since then, he hasn’t stopped working to free Albert Woodfox and Herman Wallace; together, they’re known as the Angola 3. In the early ‘70s, these Black Panthers organized other prisoners to resist degradation, violence, and death in “the bloodiest prison in the United States,” widely known as a modern slave plantation in the state of Louisiana. Convinced that they’d do so again, given the opportunity, the prison authorities have opted to keep them in isolation for decades. King spent twenty-nine years in solitary and, as of now, Woodfox and Wallace have lived in these conditions of torture for more than thirty-seven years.

King begins his autobiography, From the Bottom of the Heap (PM Press, 2009), with these words: “I was born in the U.S.A., born Black, born poor. Is it any wonder then, that I have spent most of my life in prison?” He tells his story in a clear, direct style, with a lot of details and reflections that let us know he’s also talking about the daily experience of millions of his contemporaries.

He’s grateful to his biological mother for leaving him with his grandmother, who loved him like she did her other nine sons and daughters. To him, she was Mama, the one who took care of him even though she “worked the sugar cane fields from sun up ‘til sun down for less than a dollar a day. During the off season, she washed, ironed clothes, and scrubbed floors for whites” in the small town of Gonzales, Louisiana, for pennies a day or for leftovers.

He remembers that when he was four years old, he and Mama stopped by the town jail, where a distant cousin of his worked as jailer. When the man offered him something to eat he just stared at him. He didn’t want any of that food. He noticed another Black man in the corner, behind a lot of “skinny iron” and felt a kinship with him. Mama called the man a “cornvick” and said he was probably there because he’d done something bad. As he tried to figure this out, Robert thought of the corn fields all around the town and reasoned that the man probably lived there among the cornstalks and “was considered bad for doing so.”

He cried when one of his relatives executed a dog he loved named Ring, a smart German Shepherd that was good at “finding” things ––even “shoes in pairs”! But one day Ring bit his brother James. He was slobbering and had a “fierce glare in his eyes.” King says it was commonly believed he had “gone mad,” but remembers that he looked remorseful and apologized with his eyes before he was shot through the head.

In 1947, the family moved to Algiers, that part of New Orleans on the other side of the ”muddy Mississippi River.” There, little Robert met Mule, who cared about Mama and helped her support the family, working hard when there was work to be had. He livened up his days with a little Muscatel and cheered up Robert with his sense of humor and affection. Says King: “I colored him father.”

Robert also got to know the streets of New Orleans and learned how to fight so as to survive and make friends there. Around that time, his family learned that two of his older brothers, Houston and Henry, were in prison in other cities, news that deeply saddened Mama.

When he was thirteen years old, Robert met his natural father, Hillary, and went to live with him and his wife Babs in the town of Donaldson for a couple of years. They didn’t treat him well, and his dad often hit him. He did do well in school though, and as he walked by the town’s juke joints was lucky enough to hear the sounds of Big Joe Turner, Chuck Willis, Big Mama Thornton, Ruth Brown, Jackie Wilson and many more, but his favorite was Sam Cooke. Robert finally headed back to New Orleans, leaving Hillary and Babs $50 (that he had stolen) and a note telling them that the sum should “more than cover the amount of kindness you’ve given me.”

When he couldn’t find work in Algiers, King decided to go north, to Chicaco, with dreams of making thousands of dollars to send back home to Mama. On his way out of the city, he met two white hobos, an encounter that wasn’t all that common in a South defined by apartheid. But he got lucky. They said he could tag along and shared their pocketful of nothing with him. In Chicago though, doors closed in his face and Robert got tired of sleeping on icy streets. He headed back home with the help or another hobo, but not before a YMCA director tricked him into spending three weeks in a detention center. When he got back, his feet hurt so bad he couldn’t walk. Mama’s diagnosis was frostbite, which she cured with hot rutabaga poultices.

In 1958, his compassionate sister Ruth died as a result of a botched abortion she felt compelled to have because before she could get on welfare, she had to promise not to have any more children. That was department policy for decades. Shortly thereafter, Mama went to the hospital, and the family found out she had cancer. After several treatments, they sent her home to die.

When Robert was fifteen, he was arrested because he fit the description of somebody who had robbed a gas station. He was sent to the Scotlandville Reformatory. Given the situation, he felt like things weren’t so bad. In fact, he couldn’t believe his luck to find that there were girls in the same institution! Falling in love with Cat put him in violation of a street code that prohibited a girl from going with someone new as long as her ex boyfriend was still in the reformatory. A boy could do it, but a girl couldn’t. This didn’t seem right to Robert, who kept up the romance. The ex boyfriend by the name of Pug had a reputation for being good at boxing and wanted to settle the matter in the ring. King says: “…his mechanized, predictable moves were no match for my undisciplined street style….He was admitted to the infirmary for three days. When he returned to the dormitory, he kindly gave me his blessing to continue my relationship with Cat. The code was broken. We became sort of friends.”

From that time on, things went from bad to worse for King as far as his problems with the law were concerned. A hundred years before, when the southern states replaced the “Slave Codes” with “Black Codes” to restrict the freedom of the Black population, vagrancy laws proliferated. When Robert was a teen-ager, an ordinance was still in effect that required males old enough to work to show “visible means of support.” Anyone who didn’t have a check stub or other proof could be jailed for seventy-two hours. “The 72” was especially applied to young Black men, and King went to jail on it several times, even when he did have proof of income.

One afternoon in 1961, Robert was riding around town in an old jalopy with some of his Scotlandville friends when they were arrested on suspicion of robbery by the same cop who had sent him to reform school. His three friends were identified by their victims, but since nobody identified Robert, the authorities decided that he had driven the getaway car. King says, “This theory could have been easily disproven had I been able to afford an attorney, because at the time I didn’t know beans about driving…”

Even so, he was sent to Angola Prison at the age of eighteen for the first of three times. When the twelve prisoners chained together, all Black, got out of the van, Robert felt like he “had been hurled backwards, into the past.” The way the guards talked, walked, and treated the prisoners was like something out of “a former period.” There were also a lot of prisoners who functioned as guards; they shared the guards’ contempt for the prisoners and beat them and chased them zealously when they tried to escape. In those days, around 4,000 prisoners worked on the 18,000 acre plantation for two and a half cents an hour. Two thirds of them were Black, but hardly any had office jobs; those were reserved for the white prisoners.

Angola began as a slave plantation in the middle of the nineteenth century. It was one of many southern plantations converted into prisons after the Civil War, a maneuver that allowed the dominant class to keep on profiting from the unpaid work of Black men. Today, 5,000 prisoners, 80% Black, work the same lands for between two and four cents an hour.

When Robert walked into the Angola dormitory, he was pleasantly surprised to find his uncle Henry there. He hadn’t seen him for six years. In what the young man saw as a “war zone,” where the prisoners were trapped in a disastrous pattern of “fratricide,” “suicide and self-destruction,” his uncle helped him calm down to be able to survive. At Angola, Robert learned all the tasks of growing, harvesting, and processing sugar cane. His uncle trained him in boxing and a friend named Cap Pistol taught him how to make pecan candy --pralines.

When Robert was paroled in November of 1965, at the age of twenty-two, he felt like leaving the prison alive was an accomplishment. He worked as a boxer for a few months, got married, and was about to be a father when he was entrapped in a police dragnet. His parole was revoked and he was sent back to Angola, where he worked in the fields and in the kitchen. He got to know his son in the visiting room. He no longer viewed his imprisonment as “being decreed,” as he had before; he knew who had sent him there, but he still didn’t know why.

When he was released in January of ’69, he felt like the situation in Angola was worse than it was in ’61 ––more murders, more economic slavery, more sexual slavery. But at the same time, a dramatic change had taken place in the country, and a new “Black Consciousness” was strong in New Orleans. Robert identified with this and loved to say “I’m Black and I’m Proud.” He didn’t want his young son to go through everything he’d gone through and worked hard to support him. He loved to spend time with him.

In February of 1970, at the age of twenty-eight, King was charged with a robbery committed by Wortham Jones and a forty-year-old man.” Jones named King as his accomplice, but passionately retracted his testimony during the trial, accusing the police of torturing him. It was too late. There wasn’t a shred of evidence against King, but the district attorney convinced his friends on the jury to find him guilty and sentence him to thirty-five years. It was hard for King not to stay “killing mad” with Jones, but he finally decided that the best thing to do was turn his anger against the system.

King now saw all the appeals presented by his lawyer as a mere formality. He decided to file a different kind of appeal, and along with twenty other prisoners who “also felt this need to appeal to no one but themselves,” made a break for freedom. He says that even though the plan for getting out was good, they didn’t consider the details of making themselves “invisible” once they were outside. Only three men avoided immediate capture. A few hours later, one was shot and killed, another negotiated his surrender, and only King was able to stay “invisible” for two weeks before being reported. The escape cost him a sentence of eight additional years.

King had been aware of the tremendous transformation going on in the country, especially with regards to African-Americans, but his definitive “awakening” took place when he found out that the Black Panther Party was right there in New Orleans. This happened one day when he was watching television and saw the unprecedented shootout between the police and a group of Black men and women on Desire Street in the Ninth Ward. It wasn’t long before he met them personally in the New Orleans Parish Prison.

He remembers a Panther named Cathy, who “was a source of strength to many of the prisoners” and his “greatest inspiration.” In his conversations with Ron Ailsworth, he came to understand the colonial plight of Black people as well as the dire situation of other poor people in the United States. They also talked about collectivity and “means and methods of struggle.” His introduction to the Black Panthers wasn’t limited to words. In order to make changes in the horrible prison conditions, which included a plague of huge rats and sewer water that flooded the halls where the prisoners slept on the floor, the Panthers in one part of the jail took two guards hostage, while in his section, King participated in a hunger strike with hundreds of other prisoners. Despite reprisals, they were able to call public attention to the conditions.

To King, the Black Panther ideology “defined the overall Black experience in America –– past and current” and offered alternative ways of resisting repression “politically, economically, racially, and /or socially by any means necessary,” in the tradition of Malcolm X. The struggle was seen from the perspective of downtrodden people and the goal was for “the people to be their own vanguard.” The organization wanted freedom, justice, land, bread, education, housing, and an end to police brutality and to the occupation of the Black communities. King agreed with the idea of nationalism, that is to say, with the struggle of the African-American people, and also with internationalism. It seemed logical to him that the necessary changes would only come through revolution.

It was in the New Orleans jail that King received the tragic news that his son had a brain tumor. Shortly thereafter, little Robert died at the age of five, leaving his father in tears, devastated, but with a renewed commitment to understand absolutely everything.

“In studying and learning of my enemy, I also learned of myself, my place in history….I saw that all are expendable at the system’s whim. I saw how my mother, her mother, and her mother’s mother before her suffered. I saw past generations of my forefathers stripped from their homeland, brought, by force, to these shores in chains. They were stripped of all sense of responsibility; their only obligation belonged to their servitude. I saw mothers become the predominant parental figure within the slave unit, while fathers did not know their own offspring. I was able to put some of my father Hillary’s actions into perspective. Hillary, born into a white world and dominated at every turn, felt the need himself to dominate.”

In 1971, King was transferred to Angola again. That same year, Albert Woodfox, Herman Wallace, and Ron Ailsworth, among others affiliated with the Black Panthers, had arrived and established a chapter of the party inside the prison. King got there just after a white guard named Brent Miller had been killed. For days, the entire prison was shut down. There were no visits. There were mass punishments against the Black prisoners. King was sent to a dungeon along with hundreds of other prisoners “under investigation.” They were savagely beaten, forced to run the gauntlet, stripped, and thrown into cold, bare cells. King and several others were found “guilty of wanting to play lawyer” and sent to the death house, where they experienced starvation.

Afterwards, King was isolated in the Closed Cell Restriction (CCR) area. In this seven-story unit, the prisoners were locked in their cells twenty-three hours a day, seven days a week. For years, they couldn’t go out to the yard. They could only leave their cells an hour every day to shower. On June 10, 1973, a prisoner was killed, and the eleven prisoners who happened to be out of their cells were charged with murder. Only King and Grady Brewer were found guilty based on the false testimony of two “surprise witnesses” who had been bribed. They were tried in chains with their mouths taped shut; both received life sentences.

At his time, Albert Woodfox and Heman Wallace faced charges for the murder of Brent Miller, even though they weren’t anywhere near the place where the guard was killed. Even so, they were tried and condemned for his death as a punishment for being Black Panthers. The state’s attorney relied on the false testimony of a known snitch Hezekiah Brown in the case of Woodfox, and the cooperation of Chester Jackson in the case of Wallace. King says that the court ignored the testimony of a prisoner who was mopping the floor on the morning of the murder; he testified that they only person near the scene of the crime was “a white boy.” King also mentions the “evidence” from the prison grapevine that it was Assistant Warden Hayden Dees himself who “did the unthinkable and ordered the ‘hit’ on Miller” because of his resentment at not having been named Warden. Robert says, “If true, Dees, being the racist that he was, would never have sent a Black prisoner to murder a white prison guard.”

In 1973, King volunteered to move to the “Panther Tier” to be with Woodfox and Wallace. Once there, he warned them that there was a plan to break the unity of the Panthers on the tier by sending them to different places. They made preparations and waged an all-night battle before the guards were finally able to move Woodfox and Wallace off the tier.

At times, from 1974 to 1978, when the Panthers were on the same tier, they used the hour when they were outside their cells to talk, share reading materials, and organize protests. They were able to make some changes. They put an end to the practice of having to slide their food trays under the filthy bars and forced the prison to limit the denigrating rectal searches. They made a decision to resist the searches. “We would not be willing participants in our own degradation.” They knew there would be serious consequences and that they would be separated, so they exchanged addresses and telephone numbers of relatives outside the prison. King says that they took him in chains to an office where there were rows of guards with bats, billy clubs, and other arms. “I was told to turn around and bend over. Naturally, I refused…We fought. Finally I was subdued by sheer force of numbers.” They took him to the new punishment unit, Camp J, and charged him with assaulting the officers. But “no anal examination occurred that night.” Woodfox called King’s relatives, who in turn, called the prison. “This gesture saved me from additional injuries, and perhaps death as well.” The prisoners then won a civil suit that prohibited “routine anal searches.” King says that these searches now only occur when “ ’warranted,’ whatever that means.”

King spent two years in Camp J, where the physical and psychological torture of the prisoners went unchecked. He says, “I was told by officials at that camp that what they were doing was condoned by persons in high places.” He reports that a special psychiatric unit was built at the prison, mainly for the victims of the atrocities committed at Camp J.

With regards to the terror that he experienced during his years of isolation, King says that without the appraisal of the Black Panther Party, he “could not have survived intact those twenty-nine years…this truth has sustained me.” He explains that the party’s slogan “Power to the people” comes from the concept that “power actually does belong to the people” but that people “have relinquished that power to a small faction of people called politicians” and in so doing, have left themselves “at the mercy of ever-changing restrictions defined as laws .”

For King, it is primordial to recognize prison as an extension of slavery. Supposedly abolished by the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, slavery is permitted for “people duly convicted of a crime.” He comments that “Mumia Abu-Jamal is in prison because slavery was never abolished,” as well as Jalil Al Amin, the San Francisco 8, Herman Wallace, Albert Woodfox, and Leonard Peltier. “So let’s call the prisons excatly what they are: an extenuation of slavery. And we must let the politicians know that we know this,” says King. “We the people are our own greatest resource.”

In 1988, the prisoner who had testified against King in his trial repented for having collaborated with the State. He wanted to make a public statement that he had lied. He gave King an affidavit to this effect, and shortly thereafter, another prisoner also retracted, opening a new avenue of appeals.

King says that in 1998, thanks to former Panther Malik Rahim of New Orleans, a movement mainly made up of anarchists and ex Panthers began organizing community support for the Angola Three, an effort that also attracted international support and helped win his freedom in 2001.

Since he got out of prison, King makes his living selling pecan candy that he calls “freelines.” But his real work is winning freedom for his two comrades and putting an end to the torture and slavery in the largest prison in the country, a prison that’s not an aberration, but the prototype of the modern prison industrial complex in the United States –Angola.

Says King: “I may be free of Angola, but Angola will never be free of me.”

--------------------------------------

*Also known as Robert King Wilkerson

For news on the appeals of Herman Wallace and Albert Woodfox, the suit against “cruel and unusual punishment” filed by the Angola 3, the premier of a new documentary about the case, the prisoners’ own writings, and news of the movement in their support, see: http://angola3news.blogspot.com/

To buy the book, contact: http://www.pmpress.org

SPANISH LANGUAGE VERSION:

Desde lo más bajo del montón: reseña de la autobiografía de Robert Hillary King,

x Carolina Saldaña

"Soy libre de Angola, pero Angola nunca será libre de mí", dijo el ex Pantera Negra y ex-preso político de "los 3 de Angola" al salir de la notoria plantación de esclavos en Luisiana en 2001.

A las 4:12 de la tarde el 8 de febrero de 2001, los presos igual que los familiares y simpatizantes de Robert Hillary King, también conocido como Robert King Wilkerson, gritaron su apoyo cuando él salió del infame penitenciario de Angola después de estar encerrado ahí durante más de 31 años. Desde entonces, no ha dejado de trabajar por la libertad de sus compañeros Albert Woodfox y Herman Wallace; juntos, se conocen como “los 3 de Angola”. A principios de los años ’70, estos Panteras Negras organizaron a los demás presos a resistir la degradación, violencia y muerte en “la prisión más sangrienta de Estados Unidos”, ampliamente reconocida como una moderna plantación de esclavos en el estado de Luisiana. Convencidas de que lo harían de nuevo, dada la oportunidad, las autoridades han optado por mantenerlos aislados durante décadas. King pasó 29 años solo, y hasta la fecha, Woodfox y Wallace han vivido más de 37 años en estas condiciones de tortura.

King empieza su autobiografía, Desde lo más bajo del montón (PM Press, 2009), con estas palabras: “Nací en Estados Unidos. Nací negro y pobre. ¿Es de extrañar, entonces, que he pasado la gran parte de mi vida en prisión?” Cuenta su historia personal de manera directa y sencilla, con muchos detalles y reflexiones que nos dejan saber que también está contando la experiencia diaria de millones de sus contemporáneos.

Agradece a su mamá biológica haberlo dejado con su abuela, quien lo amaba igual que sus otros nueve hijos e hijas. Para él, ella era Mama, la que los cuidaba aunque “trabajaba en los campos de caña del amanecer al atardecer por menos de un dólar diario y en temporada baja lavaba, planchaba y limpiaba el piso para los blancos” del pueblo de Gonzales, Luisiana, “por unos centavillos o por las sobras de la mesa”.

Se acuerda que cuando tenía cuatro años, pasaba con Mama por la cárcel del pueblo, donde un primo lejano trabajaba como custodio. Cuando el hombre le ofrecía comida, nada más le miró fijamente. No quería nada de esa comida. Se fijó en otro hombre negro en un rincón, tras mucho “hierro flaco” y sentía una afinidad con él. Dijo Mama que el hombre era un “cornvicto” y que ha de haber hecho algo mal para estar ahí. Al buscar el por qué, el niño se acordó de que hubo muchas milpas de maíz (corn en inglés) alrededor del pueblo y razonó que el hombre probablemente vivía ahí entre las plantas y “fue considerado malo por hacerlo”.

Lloró cuando uno de sus parientes ejecutó a su querido perro Ring, un pastor alemán muy inteligente que “encontraba” cosas ––“¡hasta zapatos en pares!” Pero un día Ring mordió a su hermano James. Estaba babeando y tuvo “una mirada feroz en sus ojos”. Se consideró que “se había vuelto loco” pero al reflexionar después, King recuerda que tenía remordimiento y que pidió disculpas con los ojos antes de recibir un disparo.

En 1947, la familia cambió de casa y de ciudad, llegando a Algiers, la parte de Nueva Orleans al otro lado del “lodoso Río Misisipi”. Ahí el pequeño Robert conoció a Mule, quien quería a Mama y se responsabilizó de ayudarle a mantener la familia, trabajando duro cuando había trabajo. Amenizó sus días con un poco de Muscatel, y los días de Robert con su buen sentido de humor y su cariño. Dice King: “Lo pinté padre”.

Robert también empezó a conocer las calles de Nueva Orleans y aprendió a pelear para sobrevivir y convivir ahí. En estos años la familia supo que dos de los hermanos mayores, Houston y Henry, estaban en prisión en otras ciudades, algo que a Mama le causó gran tristeza.

A la edad de 13, conoció a su padre natural, Hillary, y se fue a vivir con él y su esposa Babs en el pueblo de Donaldson durante un par de años. No lo trataban bien y su papá le pegó con frecuencia. Por otro lado, le iba bien en la escuela y al pasar por los antros del pueblo, tuvo la fortuna de conocer los sonidos de Big Joe Turner, Chuck Willis, Big Mama Thornton, Ruth Brown, Jackie Wilson y muchos otros, pero su cantante favorito era Sam Cooke. Por fin Robert regresó a Nueva Orleans, dejándoles a Hillary y Babs $50 (que había robado) y una nota diciendo que esta cantidad de dinero “debe ser más que suficiente para cubrir todo el cariño que ustedes me han mostrado”.

Al no encontrar trabajo en Algiers, tomó la decisión de ir al Norte—a Chicago–, con sueños de ganar miles de dólares para enviar a Mama. En camino conoció a dos vagabundos blancos, un encuentro poco usual en el mundo de apartheid del Sur de Estados Unidos. Corrió suerte. Ellos permitieron que los acompañara y compartieron la nada que tenían con él. Pero en Chicago también las puertas le estaban cerradas, y Robert se cansó de dormir en calles cubiertas de hielo. Regresó a casa con la ayuda de otro vagabundo, pero no antes de que un oficial de la YMCA le tendiera una trampa, haciéndolo pasar tres semanas en un centro de detención. Al regresar, sus pies le dolían tanto que no pudo caminar. Según el diagnóstico de Mama, fue un caso de congelación, y ella le curó con cataplasmas de nabo sueco.

En 1958, su hermana compasiva Ruth murió en un aborto mal hecho que ella se sintió obligada a pedir porque para recibir la asistencia social que necesitaba, tenía que prometer no tener más hijos. Ésta fue la política del Departamento de Servicio Social durante décadas. Un poco después, Mama se fue al hospital y la familia supo que ella tenía cáncer. Después de varias visitas la enviaron a casa a morir.

Cuando tenía 15 años, Robert fue detenido porque cuadraba con la descripción de alguien que había robado una gasolinera. Lo enviaron al reformatorio de Scotlandville. Sintió que dentro de lo que cabía, no le fue tan mal. De hecho, no pudo creer su suerte al encontrar que ¡hubo chicas en la misma institución! Al enamorarse de Cat, se encontró en violación de un código callejero que prohibía a una chica andar con alguien mientras su ex novio todavía estaba en el reformatorio. Un chavo podía hacerlo, pero una chava, no. Esto no le pareció bien a Robert, quien siguió con el romance. El otro, que se llamaba Pug, tenía fama de boxeador y quería arreglar el asunto en el ring. Dice King: “Sus movimientos mecanizados y predecibles no estaban al nivel de mi estilo callejero.…Él se fue al hospital durante tres días y cuando salió, muy amablemente me dio su bendición para seguir mi relación con Cat. Se rompió el código. Éramos amigos, más o menos.”

De ahí en adelante, las cosas fueron de mal en peor para King con respecto a sus problemas con la ley. Unos cien años atrás, cuando los estados sureños reemplazaron sus “códigos de esclavitud” con “los códigos negros” para restringir la libertad de la población negra, las leyes contra la vagancia proliferaban. Durante la juventud de Robert, todavía estaba en efecto una ordenanza que requería que una persona llevara consigo pruebas de sus medios de apoyo. Si no tenía el requerido boleto o un recibo, podría ser encarcelado durante 72 horas. La ordenanza “72” fue especialmente aplicada contra los jóvenes negros, y a King le tocó la cárcel varias veces, incluso cuando pudo comprobar sus ingresos.

Una tarde en 1961, Robert andaba en una carcacha con unos amigos de Scotlandville, cuando fueron detenidos bajo sospecho de robo por el mismo policía que lo había enviado al reformatorio. Sus tres amigos fueron identificados por las víctimas, pero como nadie señaló a Robert, las autoridades decidieron que él ha de haber manejado el coche en que huyeron. Dice King: “Esta teoría podría haber sido fácilmente rebatida si yo hubiera tenido el dinero para contratar a un abogado, porque yo ni siquiera sabía cómo manejar un coche”.

Sin embargo, el joven de 18 años fue enviado al penitenciario de Angola por la primera de tres veces. Cuando los 12 presos encadenados juntos, todos negros, bajaron de la camioneta y entraron por la puerta de la prisión, Robert sintió que “había sido arrojado para atrás, hacia el pasado”. La manera en que los custodios hablaban, caminaban y trataban a los presos era “de otra época”. También hubo muchos presos que funcionaban como guardias, quienes compartían el mismo desprecio para los presos y los golpeaban y perseguían con ganas si intentaban escapar. En aquel entonces, alrededor de 4,000 presos trabajaban en la plantación de 7,400 hectáreas por dos centavos y medio cada hora. Dos tercios eran negros, de los cuales casi ninguno trabajaba en las oficinas; estos puestos fueron reservados para los presos blancos.

Angola nació como una plantación de esclavos a mediados del siglo diecinueve. Era una de las muchas plantaciones del Sur convertidas en prisiones después de la Guerra Civil, una maniobra que permitió que la clase dominante siguiera sacando ganancias del trabajo no remunerado de los Negros. Hoy en día, 5,000 presos, 80% de los cuales son negros, trabajan las mismas tierras por entre dos y cuatro centavos la hora.

Al entrar en el dormitorio de Angola, fue una grata sorpresa para Robert encontrar ahí a su tío Henry; no lo había visto desde hace seis años. En lo que el joven describe como una “zona de guerra”, donde vio a los presos atrapados en un desastroso patrón de “fratricidio”, “suicidio y auto-destrucción”, su tío le ayudó a calmarse para poder sobrevivir. En Angola, Robert aprendió todos los aspectos de cultivar, cosechar y procesar caña. Su tío le instruyó en el boxeo, y un amigo llamado Cap Pistol le enseñó a hacer pralines ––dulces de azúcar y nuez.

Cuando salió del penitenciario bajo libertad condicional en noviembre de 1965, a la edad de 22, sintió que fue un logro haber salido vivo de ahí. Trabajó en el boxeo unos meses, se casó y estaba para ser papá cuando fue atrapado en una operación encubierta. Su libertad condicional fue revocada, y fue enviado a Angola de nuevo, donde trabajó en el campo y en la cocina. Conoció a su hijo en el cuarto de visitas. Ya no vio su encarcelamiento como su destino, como antes; sabía quién lo había enviado ahí pero aún no sabía por qué.

Cuando salió en enero de ’69 sintió que la situación en Angola era peor que en ’61 –más homicidios, más esclavitud económica, más esclavitud sexual. Pero también había ocurrido un dramático cambio en la ciudad, y el impulso a la “Consciencia Negra” estuvo fuerte en Nueva Orleans. Robert se identificó con esto y le gustaba decir “Soy Negro y soy orgulloso”. No quería que su pequeño hijo sufriera lo que él había sufrido y trabajó duro para mantenerlo. Disfrutó enormemente del tiempo que pasó con él.

En febrero de 1970, a la edad de 28, King fue incriminado por un robo cometido por Wortham Jones y alguien descrito como un señor de 40 años. Jones nombró a King como su cómplice, pero durante el juicio retractó su testimonio de manera enfática, acusando a la policía de torturarlo. Ya era tarde. No hubo una sola prueba contra King, pero el fiscal convenció a sus amigos del jurado a encontrarlo culpable y sentenciarlo a 35 años. Aunque a King le costó trabajo no guardarle “una rabia asesina” a Jones por colaborar en robarle la vida, pasó muchas hora reflexionando sobre sus motivos y su retractación. Por fin tomó la decisión de dirigir esa rabia contra el sistema.

King ya consideraba las apelaciones presentadas por su abogado una mera formalidad. Quería “apelar” de otra manera, y con otros 20 reos que también sentían la necesidad de “apelar sólo a sí mismos”, salió corriendo de la cárcel. Dice que aunque la fuga fue bien planeada, descuidaban los detalles de cómo mantenerse invisibles fuera de los muros. Sólo tres lograron evitar la captura inmediata. Unas horas después, uno de ellos recibió una bala fatal, otro negoció su entrega, y solo King se mantuvo “invisible” durante dos semanas antes de que alguien lo delatara. La fuga le costó una sentencia de ocho años adicionales.

King había estado consciente de la tremenda transformación que estaba ocurriendo en el país, especialmente con respecto a los Africano-americanos, pero su despertar definitorio ocurrió cuando se enteró de la presencia del partido Panteras Negras ahí mismo en Nueva Orleans. Esto ocurrió cuando vio en la tele la balacera sin precedente entre la policía y un grupo de hombres y mujeres negros en la Calle Desire. No tardó mucho en conocerlos personalmente en la cárcel de Nueva Orleans.