From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

SF Disabled Rights, Police Shooting, Courts Labor & Conard Housing And USW Strike Lessons

A recent US Supreme Court decision about disability rights and police attacks centers on the role of the San Francisco police shooting of Theresa Sheehan at the Conard Co-operative Housing. It also raises the question of so called "non-profits" and the privatization of public housing and oversight by the City and County Of San Francisco. The program also hears from USW 5 Tesoro strikers and the firing of union health and safety activists

Public Housing Privatization, Conard Housing, Disability Rights, The Supreme Court and USW 5 Tesoro Oil Strikers Fight Retaliation

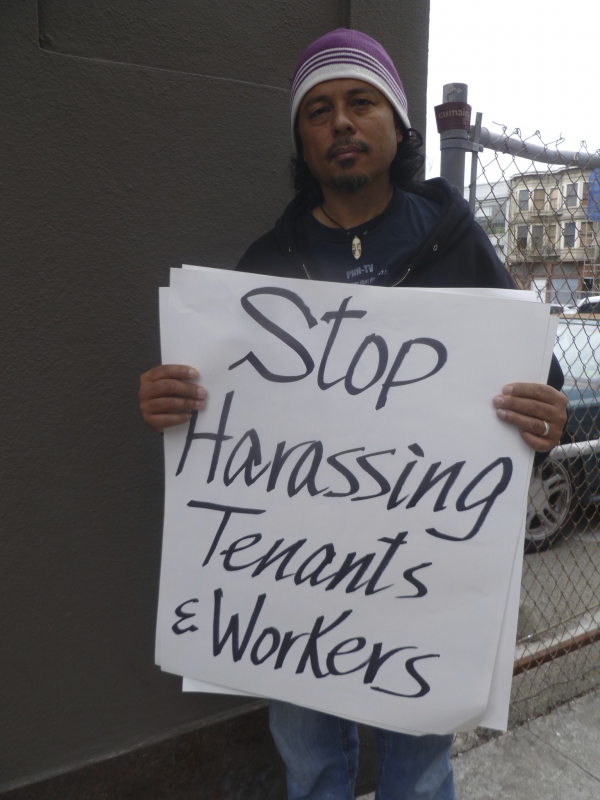

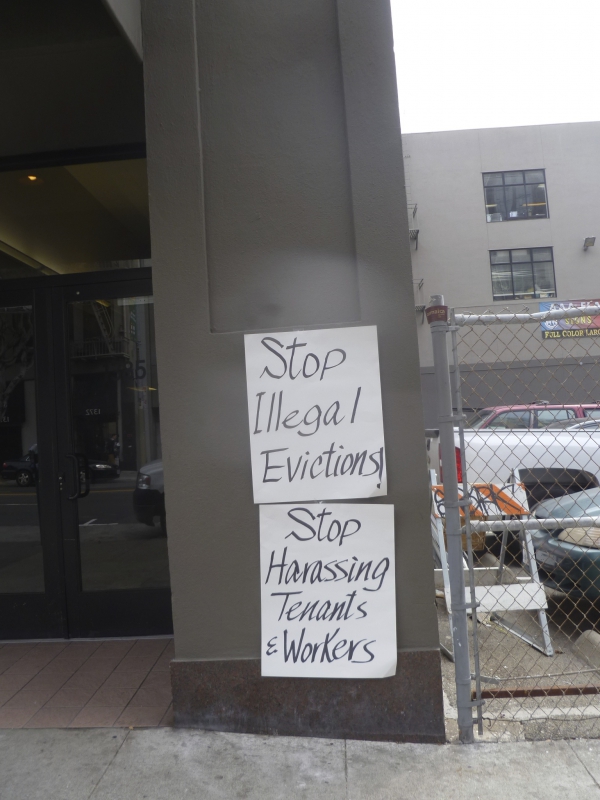

WorkWeek looks at the recent US Supreme Court hearing on the police attack on disabled tenant Theresa Sheehan who resided at the Conard Co-operative Housing in San Francisco and was shot by the police 6 times. It also focuses on the privatization of public housing going on in San Francisco, the East Bay and nationally and how this is affecting tenants, workers and creating more homeless.

Guests include Brenda Barros, SEIU 1021SF COPE Co-Chair, Claudia Center, ACLU Senior Attorney For Disability Rights and Lynda Carson, East Bay Public Housing Advocate and Tenants Rights Advocate.

WorkWeek also hears from USW 5 Tesoro Pacheco union leader Criff Reyes about the retaliation of union activists and the strike against Tesoro.

Production of WorkWeek Radio

workweek [at] kpfa.org

An Eviction Nightmare at Oregon Park Senior Apartments In Berkeley

A Berkeley complex for low-income seniors has threatened to evict outspoken residents, raising fears about the potential loss of affordable housing.

http://www.eastbayexpress.com/oakland/an-eviction-nightmare-at-oregon-park-senior-apartments/Content?oid=4229738

By Sam Levin @SamTLevin

• BERT JOHNSON

• Kevin Wiggins.

For ten years, Oregon Park Senior Apartments in South Berkeley has operated as a nonprofit cooperative for low-income senior citizens. That means the sixty-unit complex at 1425 Oregon Street is resident-controlled with tenants electing a board that is in charge of day-to-day operations. The complex provides a critical source of affordable housing — predominantly for people of color. But in recent months has suffered from a number of internal disputes and legal battles that have greatly threatened the stability of the cooperative.

While much of the conflict stems from an ongoing disagreement about the board leadership, housing attorneys said they were especially concerned about the board's attempts to evict a number of outspoken tenants. Earlier this year, Ibrahim Moss, a management consultant, served eviction notices to at least nine residents — and subsequently filed eviction lawsuits against at least four of them, according to the East Bay Community Law Center, a nonprofit assisting the residents.

Brendan Darrow, law center staff attorney and clinical supervisor, who is representing five Oregon Park tenants, said the evictions were clearly retaliatory and violated numerous housing laws. Some of the three-day eviction notices — which tenants and Darrow shared with me — essentially informed residents that they were required to stop speaking out. The letters went to residents who had publicly criticized the board of directors about a number of concerns, according to Darrow and multiple tenants.

The notices from Moss informed residents that they had to stop organizing meetings aimed at unseating the current board; making any "false complaints to public officials, private entities, or any persons or institutions, that related to Oregon Park Senior Apartment's Board of Directors, managers, contractors or any related persons or interests"; and presenting themselves as "member[s] in good standing" at the cooperative.

"The lawsuits were so blatantly retaliatory and designed to suppress free speech and public participation," Darrow said.

What's more, in separate court filings, Moss wrote detailed personal attacks against a number of the tenants he has tried to evict, calling one resident a "gross, if not vile and intimidating personality" and labeling another an "unemployed birdwatcher." Moss wrote about the latter tenant: "While having no regular income, he has ... manage [sic] to purchase a brand new hybrid automobile, enjoy lavish and extended vacations ... and indulge in other luxuries. ... Not bad for an unemployed man."

What's even more troubling is that Moss failed to cash the rent checks of two of the tenants who were sued by the board, Kevin Wiggins and Juanita Edington, and instead returned them to the residents, according to Darrow and those two tenants. In other words, as part of the eviction cases, Moss was accusing the tenants of owing rent, but was refusing to accept their checks, Darrow said, noting that this is an illegal practice.

The eviction notices also failed to include a phone number for Moss, which is legally required. For that reason, last week, a judge dismissed the four eviction lawsuits that Moss had filed against the tenants. But given that the Oregon Park board could re-file against these individuals at any time, tenants said they remained fearful.

"I [am] in shock and disbelief," said Wiggins. "This is a member-managed property and we have every right to speak up. But they are suppressing our civil rights. ... They wanted us gone."

Reached by phone last week, Andre Nibbs, president of the Oregon Park board, declined to comment. In a series of lengthy emails to me, Katherine Wenger, an attorney representing the board, refuted the allegations made by Darrow and the residents, saying the board sought to evict tenants simply because they owed rent. She also downplayed the judge's decision to throw out the eviction cases saying the ruling was based on "procedural issues," adding that "these dismissals had nothing to do with the merits of the cases."

Wenger further asserted that Nibbs never returned any rent checks and had instructed Moss to accept checks. Moss, she added, recently resigned, but she declined to say why. Moss did not respond to multiple emails from me last week. Wenger also contended that the retaliation allegations were false.

Darrow, however, argued that the sole reason Edington and Wiggins apparently owed rent was because Moss refused to accept their payments. The other two tenants whose evictions were dismissed had fallen behind on rent, but had longstanding written agreements in place establishing payment plans, which they were properly following, according to Darrow. He also pointed out that Oregon Park accounting records he reviewed showed that other tenants who had outstanding rent payments did not receive eviction notices. He said this further suggested that Moss targeted certain tenants specifically because they had been outspoken.

Residents who have criticized the board have a long list of grievances, court filings show. A group of them accused the board of appointing members without following proper election procedures; firing a bookkeeper and maintenance worker without getting required board approval; hiring Moss, the consultant, without board review or contract approval; closing the management office and shutting off telephone service; and denying residents the opportunity to participate in public meetings.

The board has denied those allegations, but the internal conflict has seriously threatened the cooperative's operations. JPMorgan Chase, the bank that maintains Oregon Park's accounts, recently froze the cooperative's accounts as a result of the ongoing disputes and confusion around who has a right to access funds. The bank wrote in court filings that it has "reasonable doubt as to whether the current board was properly elected," and noted that the board failed to provide any documentation confirming that it had hired Moss or that Moss had the authority to act as an agent for the cooperative.

It's unclear what will happen if the bank and the residents can't resolve the dispute — a Chase spokesperson declined to comment — but some fear the property could face foreclosure if residents and board leaders can't reach a consensus and convince the bank to re-open the accounts. "We could lose our homes because the bank has foreclosed on it," said resident Vic Coffield, who helped organize a protest two weeks ago in which he demanded financial transparency from the board. "We could lose this place, and it's all because the board disappeared."

The board, with Wenger's assistance, has requested that the court appoint a so-called "receiver," meaning a paid third-party individual to operate Oregon Park, but some residents told me they opposed this effort, because they want the complex to remain a resident-controlled cooperative. Tenants have organized a March 28 meeting at which they hope to elect new board leaders.

Earlier this month, at a resident-organized meeting — which drew dozens of tenants, though board leaders did not show up — residents said they were afraid that their funds were being mismanaged and depleted for legal fees.

"They are using our money to fight us," resident Dale Anders told the group. Anders showed me a three-day eviction notice he received — he was not one of Darrow's clients — and said it was clearly retribution for speaking up. "I did not deserve this," he said, adding, "This is very stressful. I couldn't sleep for a month."

Contact the author of this piece, send a letter to the editor, like us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter.

http://soundcloud.com/ workweek-radio

Supreme Court weighs S.F. police shooting of mentally ill woman

http://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/Supreme-Court-weighs-S-F-police-shooting-of-6153801.php

By Bob EgelkoMarch 23, 2015

Photo: Molly Riley / Associated Press

Image 2of 2

This handout photo provided by Patricia C. Sheehan, taken Dec. 25, 2013, shows Teresa Sheehan. The Supreme Court on March 23, 2015, will consider whether police must take special precautions when trying to arrest a person who is mentally ill. The case centers on Teresa Sheehan. Police forced their way into her room at a group home after she threatened her social worker and when she came at them with a knife, officers shot her five times. Lawyers for Sheehan say the Americans With Disabilities Act requires police to make reasonable accommodations when arresting people who have mental or physical disabilities. (AP Photo/Patricia C. Sheehan)

IMAGE 1 OF 2

John Burris, of the Law Offices of John L. Burris representing Teresa Sheehan, walks out after the Supreme Court heard arguments in San Francisco v. Sheehan, at the Supreme Court in Washington, Monday, March 23, 2015. Also shown are Frances Sheehan, left, and Joanne Sheehan, both sisters of Teresa Sheehan. (AP Photo/Molly Riley)

Wrestling with the case of a knife-wielding San Francisco woman who was shot in her room at a group home by city police officers, U.S. Supreme Court justices seemed inclined Monday to give police some leeway in dealing with mentally ill, potentially violent suspects.

When officers are facing someone who is armed and “may be violent at any time,” there is “some reason to give the police officers who have to deal with them the benefit of the doubt,” Justice Elena Kagan told a lawyer for Teresa Sheehan, who survived the 2008 shooting and is suing the city for damages.

The liberal Kagan appeared to be aligned with conservative Justice Antonin Scalia, who — referring to the legal requirement to “reasonably accommodate” a person’s physical or mental disability — declared, “It is never reasonable to accommodate somebody who is armed and violent, period.”

But no clear standard for applying the Americans with Disabilities Act to police confrontations, the central issue in the case, emerged from the one-hour hearing. At least one justice, Sonia Sotomayor, suggested that the law could play a constructive role in avoiding unnecessary harm to the mentally ill.

The ADA, Sotomayor said, was “intended to ensure that police officers try mitigation in these situations before they jump to violence.” The alternative, she said, may be “a society in which the mentally ill are automatically killed,” citing a report that about 350 mentally impaired individuals each year are fatally shot by police in the United States.

In San Francisco, disability-rights groups told the court, more than half of the 19 people fatally shot by police between 2005 and 2013 had psychiatric disabilities. Monday’s hearing took place three weeks after Los Angeles police shot and killed a mentally ill, homeless man who had undergone psychiatric treatment in federal prison before his release last year.

In response to Sotomayor, San Francisco’s lawyer, Deputy City Attorney Christine Van Aken, said the federal disability law was not intended to require measures short of force when officers are at risk.

“If the individual presents a significant threat, then no accommodation is required,” Van Aken told the court. Even if an armed suspect ignored an officer’s command to put his hands up because he was deaf, and the officer knew that, she said, the officer would nevertheless be entitled to shoot the suspect if necessary to “protect public safety.”

Police were summoned to a Mission District group home in August 2008 by a social worker who said Sheehan, a 56-year-old resident who suffered from schizophrenia, had a knife and had threatened to kill him.

Sgt. Kimberly Reynolds and Officer Katherine Holder entered her room and said Sheehan came at them with a knife. They left and called for backup, but re-entered shortly before help arrived, breaking down the door when Sheehan tried to block it. The officers explained later that they feared Sheehan might have access to other weapons or escape from the room.

They tried to subdue her with pepper spray, but she continued to wield the knife, and the officers then shot her five or six times. Sheehan needed two hip-replacement operations because of her wounds, her lawyer said.

She was charged with assault, but a jury deadlocked and prosecutors dropped the case. Her damage suit accuses the police of using excessive force and violating her rights as a disabled person. The suit was dismissed by U.S. District Judge Charles Breyer but reinstated in February 2014 by the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, which said a jury could find the officers’ second entry and subsequent use of force unjustified.

The Supreme Court took up the case primarily to decide how the Americans with Disabilities Act applies to police encounters with the mentally ill. San Francisco, joined by other cities and counties and police organizations, argued that the ADA, which requires government agencies to make allowances for physical and mental impairments in their practices, doesn’t apply to armed suspects whom police consider to be dangerous.

The Obama administration largely sided with San Francisco, arguing that police are justified in using force unless they know the individual poses no threat to the public.

It might be different, Justice Department lawyer Ian Gershengorn told the court, if officers could see the suspect had no chance to escape — for example, if a mentally ill person with a knife was cornered in an alley, or if a security camera had allowed the police to look into Sheehan’s room and had seen her huddled in a corner.

That didn’t satisfy Justice Anthony Kennedy, who told Gershengorn his standard “gives no guidance at all to an officer faced ... with a violent person.”

Sheehan drew allies from disability-rights groups and mental health organizations, who argued that a jury should decide whether she posed a threat and whether the officers could have waited her out, brought in a negotiator or taken other measures without resorting to violence.

“The way to interact with mentally disabled individuals is through communication and time,” said Sheehan’s lawyer, Leonard Feldman. “Police officers know that, and they’re trained that way.”

A ruling is due by the end of June. The case is San Francisco vs. Sheehan, 13-1412.

Bob Egelko is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. E-mail: begelko [at] sfchronicle.com

Twitter: @egelko

Justices skeptical that disability law applies to armed, violent suspects who are mentally ill

http://www.usnews.com/news/politics/articles/2015/03/23/supreme-court-considers-impact-of-disability-law-on-police

<85.jpeg>

This handout photo provided by Patricia C. Sheehan, taken Dec. 25, 2013, shows Teresa Sheehan. The Supreme Court on March 23, 2015, will consider whether police must take special precautions when trying to arrest a person who is mentally ill. The case centers on Teresa Sheehan. Police forced their way into her room at a group home after she threatened her social worker and when she came at them with a knife, officers shot her five times. Lawyers for Sheehan say the Americans With Disabilities Act requires police to make reasonable accommodations when arresting people who have mental or physical disabilities. (AP Photo/Patricia C. Sheehan)

Associated PressMarch 23, 2015 | 3:17 p.m. EDT+ More

BY SAM HANANEL, Associated Press

WASHINGTON (AP) — The Supreme Court on Monday seemed skeptical that the nation's disabilities law requires police to take special precautions when arresting armed and violent suspects who are mentally ill. Most justices expressed doubts about second-guessing police who are trying to protect public safety.

The justices heard arguments in a dispute over how San Francisco police in 2008 dealt with a woman with schizophrenia who had threatened to kill her social worker. Police ultimately forced their way into Teresa Sheehan's room at a group home, then shot her after she came at them with a knife.

Sheehan survived and later sued the city, claiming police had a duty under the Americans with Disabilities Act to consider her mental illness and take more steps to avoid a violent confrontation.

The case comes as police have been criticized for a series of high-profile incidents where suspects with mental illness have been shot and killed — most recently an unarmed, naked man in an apartment complex outside Atlanta.

San Francisco agrees that the ADA requires public officials to make "reasonable accommodations" to avoid discriminating against people with disabilities, but Deputy City Attorney Christine Van Aken told the justices that it doesn't apply "if the individual presents a significant threat."

Justice Antonin Scalia seemed to take the city's side, but he wondered whether the court should have taken up the case in the first place. Scalia grilled Van Aken about why the city seemed to change its legal tack after the high court had agreed to hear the case.

The city originally seemed to claim that the ADA didn't apply at all to police arrests, Scalia said, but later acknowledged that it did apply, except when armed and violent suspects pose a direct threat.

"There's a technical word for this," Scalia said. "It's called bait-and-switch."

Van Aken insisted that the city had consistently argued that there is no accommodation under the ADA "where there are exigent circumstances."

Sheehan's lawyer, Leonard Feldman, said he would welcome it if the court simply dismissed the case and sent it back to the lower courts. Then, a jury could decide whether police should have used less aggressive tactics, such as waiting for backup and trying to talk to her in a nonthreatening way. That's what the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled after a federal district judge initially threw the case out.

"The entire risk that officers confronted was avoidable," Feldman said.

The Obama administration tried to stake out a middle ground. Deputy Solicitor General Ian Gershengorn told the justices that when a mentally ill person is armed and violent, police should only change tactics if the person is "contained and visible."

That didn't seem to satisfy Justice Anthony Kennedy.

"I think the standard you've just proposed gives no guidance at all to an officer faced with a violent person," Kennedy said.

The case has attracted attention from mental health advocates who say that failing to take account of a suspect's disability often results in unnecessary shootings by police. Lower courts have split on when and how the law should apply to police conduct when public safety is at risk.

Law enforcement groups have also weighed in, saying a ruling in Sheehan's favor could undermine police tactics, place officers and bystanders at risk and open them to additional liability.

In Sheehan's case, her social worker called police for help in restraining her so she could be taken to a hospital for treatment. Officers entered her room with a key, but Sheehan threatened them with a knife, so they closed the door and called for backup. But they said they weren't sure whether Sheehan had a way to escape, and were concerned that she might have other weapons inside.

How Police Can Stop Shooting People With Disabilities

https://www.aclu.org/blog/criminal-law-reform-free-speech/how-police-can-stop-shooting-people-disabilities

03/20/2015

Disability Rights

By Claudia Center, Senior Staff Attorney, ACLU at 1:59pm

Hundreds of Americans with disabilities die each year in police encounters, and many more are seriously injured. On Monday, the U.S. Supreme Court will hear oral argument in a case about one of these interactions.

In San Francisco v. Sheehan, police were called to take Teresa Sheehan – a woman having a psychiatric emergency – to the hospital. Instead of helping Ms. Sheehan get treatment, the officers ended up shooting her five times. She survived and sued. At issue is whether and how the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) applies to interactions between police and people with disabilities.

The Supreme Court is weighing in against a backdrop of news stories detailing a seemingly unending stream of officer-involved shootings. The dead and wounded are mostly persons with mental disabilities and young men of color. Many – such as Jason Harrison, Anthony Hill, and Kajieme Powell – are both.

Police shootings of persons with mental disabilities tend to follow a pattern. Someone calls the police about a person in crisis. The police arrive, but the person in crisis fails to immediately follow police commands, not because the person is a “criminal” but because they are experiencing a crisis related to their mental disability.

In response to the person’s noncompliance, the officers start shouting and draw their weapons. They may surround the individual or spray them with mace. The crisis escalates. In a panicked effort to resist, the person grabs a nearby object – a knife, a screwdriver, a pen, a mop. The officers fire. Usually the disabled person dies.

There is a safer way for police to interact with persons with mental disabilities in crisis. In communities across the country, officers are trying to resolve these situations without resort to lethal force by using accepted crisis intervention and de-escalation tools, including calm communication, collaboration with mental health resources, physical containment of the individual from a distance, and patience.

These kinds of strategies should be considered reasonable accommodations under the ADA, as the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled. Their use could have prevented the near-fatal shooting of Ms. Sheehan.

In Ms. Sheehan’s case, the officers knew from the outset that they were dealing with a disability crisis situation. When they found Ms. Sheehan quiet and contained within her room, they had the opportunity to use their crisis intervention training. They could have surveyed the premises, consulted with command on strategies, and used calm communication to try to convince Ms. Sheehan to go with them to the psychiatric hospital.

They didn’t.

Without a clear plan for a safe interaction, the officers entered Ms. Sheehan’s locked second-story room without her permission. Twice. The second time they did so with force, shouting, spraying mace, and with guns drawn. When Ms. Sheehan brandished a bread knife, the officers fired multiple times at close range. She almost died. She spent months in the hospital and rehab and has permanent physical injuries.

The safer strategies are neither expensive nor complicated, but their implementation requires a commitment to change. Law enforcement must adopt ADA-compliant policies, practices, and trainings that require safer policing strategies for people with disabilities and that honestly assess bad outcomes after the fact.

If the Supreme Court rules that Ms. Sheehan somehow is not protected by the ADA, then the decades-long movement to achieve safer police interactions with individuals with disabilities will suffer a devastating setback. Such an outcome could eliminate one of the few legal mandates available to combat the terrible cycle of avoidable police shootings and killings. A call for help shouldn’t result in death.

WorkWeek looks at the recent US Supreme Court hearing on the police attack on disabled tenant Theresa Sheehan who resided at the Conard Co-operative Housing in San Francisco and was shot by the police 6 times. It also focuses on the privatization of public housing going on in San Francisco, the East Bay and nationally and how this is affecting tenants, workers and creating more homeless.

Guests include Brenda Barros, SEIU 1021SF COPE Co-Chair, Claudia Center, ACLU Senior Attorney For Disability Rights and Lynda Carson, East Bay Public Housing Advocate and Tenants Rights Advocate.

WorkWeek also hears from USW 5 Tesoro Pacheco union leader Criff Reyes about the retaliation of union activists and the strike against Tesoro.

Production of WorkWeek Radio

workweek [at] kpfa.org

An Eviction Nightmare at Oregon Park Senior Apartments In Berkeley

A Berkeley complex for low-income seniors has threatened to evict outspoken residents, raising fears about the potential loss of affordable housing.

http://www.eastbayexpress.com/oakland/an-eviction-nightmare-at-oregon-park-senior-apartments/Content?oid=4229738

By Sam Levin @SamTLevin

• BERT JOHNSON

• Kevin Wiggins.

For ten years, Oregon Park Senior Apartments in South Berkeley has operated as a nonprofit cooperative for low-income senior citizens. That means the sixty-unit complex at 1425 Oregon Street is resident-controlled with tenants electing a board that is in charge of day-to-day operations. The complex provides a critical source of affordable housing — predominantly for people of color. But in recent months has suffered from a number of internal disputes and legal battles that have greatly threatened the stability of the cooperative.

While much of the conflict stems from an ongoing disagreement about the board leadership, housing attorneys said they were especially concerned about the board's attempts to evict a number of outspoken tenants. Earlier this year, Ibrahim Moss, a management consultant, served eviction notices to at least nine residents — and subsequently filed eviction lawsuits against at least four of them, according to the East Bay Community Law Center, a nonprofit assisting the residents.

Brendan Darrow, law center staff attorney and clinical supervisor, who is representing five Oregon Park tenants, said the evictions were clearly retaliatory and violated numerous housing laws. Some of the three-day eviction notices — which tenants and Darrow shared with me — essentially informed residents that they were required to stop speaking out. The letters went to residents who had publicly criticized the board of directors about a number of concerns, according to Darrow and multiple tenants.

The notices from Moss informed residents that they had to stop organizing meetings aimed at unseating the current board; making any "false complaints to public officials, private entities, or any persons or institutions, that related to Oregon Park Senior Apartment's Board of Directors, managers, contractors or any related persons or interests"; and presenting themselves as "member[s] in good standing" at the cooperative.

"The lawsuits were so blatantly retaliatory and designed to suppress free speech and public participation," Darrow said.

What's more, in separate court filings, Moss wrote detailed personal attacks against a number of the tenants he has tried to evict, calling one resident a "gross, if not vile and intimidating personality" and labeling another an "unemployed birdwatcher." Moss wrote about the latter tenant: "While having no regular income, he has ... manage [sic] to purchase a brand new hybrid automobile, enjoy lavish and extended vacations ... and indulge in other luxuries. ... Not bad for an unemployed man."

What's even more troubling is that Moss failed to cash the rent checks of two of the tenants who were sued by the board, Kevin Wiggins and Juanita Edington, and instead returned them to the residents, according to Darrow and those two tenants. In other words, as part of the eviction cases, Moss was accusing the tenants of owing rent, but was refusing to accept their checks, Darrow said, noting that this is an illegal practice.

The eviction notices also failed to include a phone number for Moss, which is legally required. For that reason, last week, a judge dismissed the four eviction lawsuits that Moss had filed against the tenants. But given that the Oregon Park board could re-file against these individuals at any time, tenants said they remained fearful.

"I [am] in shock and disbelief," said Wiggins. "This is a member-managed property and we have every right to speak up. But they are suppressing our civil rights. ... They wanted us gone."

Reached by phone last week, Andre Nibbs, president of the Oregon Park board, declined to comment. In a series of lengthy emails to me, Katherine Wenger, an attorney representing the board, refuted the allegations made by Darrow and the residents, saying the board sought to evict tenants simply because they owed rent. She also downplayed the judge's decision to throw out the eviction cases saying the ruling was based on "procedural issues," adding that "these dismissals had nothing to do with the merits of the cases."

Wenger further asserted that Nibbs never returned any rent checks and had instructed Moss to accept checks. Moss, she added, recently resigned, but she declined to say why. Moss did not respond to multiple emails from me last week. Wenger also contended that the retaliation allegations were false.

Darrow, however, argued that the sole reason Edington and Wiggins apparently owed rent was because Moss refused to accept their payments. The other two tenants whose evictions were dismissed had fallen behind on rent, but had longstanding written agreements in place establishing payment plans, which they were properly following, according to Darrow. He also pointed out that Oregon Park accounting records he reviewed showed that other tenants who had outstanding rent payments did not receive eviction notices. He said this further suggested that Moss targeted certain tenants specifically because they had been outspoken.

Residents who have criticized the board have a long list of grievances, court filings show. A group of them accused the board of appointing members without following proper election procedures; firing a bookkeeper and maintenance worker without getting required board approval; hiring Moss, the consultant, without board review or contract approval; closing the management office and shutting off telephone service; and denying residents the opportunity to participate in public meetings.

The board has denied those allegations, but the internal conflict has seriously threatened the cooperative's operations. JPMorgan Chase, the bank that maintains Oregon Park's accounts, recently froze the cooperative's accounts as a result of the ongoing disputes and confusion around who has a right to access funds. The bank wrote in court filings that it has "reasonable doubt as to whether the current board was properly elected," and noted that the board failed to provide any documentation confirming that it had hired Moss or that Moss had the authority to act as an agent for the cooperative.

It's unclear what will happen if the bank and the residents can't resolve the dispute — a Chase spokesperson declined to comment — but some fear the property could face foreclosure if residents and board leaders can't reach a consensus and convince the bank to re-open the accounts. "We could lose our homes because the bank has foreclosed on it," said resident Vic Coffield, who helped organize a protest two weeks ago in which he demanded financial transparency from the board. "We could lose this place, and it's all because the board disappeared."

The board, with Wenger's assistance, has requested that the court appoint a so-called "receiver," meaning a paid third-party individual to operate Oregon Park, but some residents told me they opposed this effort, because they want the complex to remain a resident-controlled cooperative. Tenants have organized a March 28 meeting at which they hope to elect new board leaders.

Earlier this month, at a resident-organized meeting — which drew dozens of tenants, though board leaders did not show up — residents said they were afraid that their funds were being mismanaged and depleted for legal fees.

"They are using our money to fight us," resident Dale Anders told the group. Anders showed me a three-day eviction notice he received — he was not one of Darrow's clients — and said it was clearly retribution for speaking up. "I did not deserve this," he said, adding, "This is very stressful. I couldn't sleep for a month."

Contact the author of this piece, send a letter to the editor, like us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter.

http://soundcloud.com/ workweek-radio

Supreme Court weighs S.F. police shooting of mentally ill woman

http://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/Supreme-Court-weighs-S-F-police-shooting-of-6153801.php

By Bob EgelkoMarch 23, 2015

Photo: Molly Riley / Associated Press

Image 2of 2

This handout photo provided by Patricia C. Sheehan, taken Dec. 25, 2013, shows Teresa Sheehan. The Supreme Court on March 23, 2015, will consider whether police must take special precautions when trying to arrest a person who is mentally ill. The case centers on Teresa Sheehan. Police forced their way into her room at a group home after she threatened her social worker and when she came at them with a knife, officers shot her five times. Lawyers for Sheehan say the Americans With Disabilities Act requires police to make reasonable accommodations when arresting people who have mental or physical disabilities. (AP Photo/Patricia C. Sheehan)

IMAGE 1 OF 2

John Burris, of the Law Offices of John L. Burris representing Teresa Sheehan, walks out after the Supreme Court heard arguments in San Francisco v. Sheehan, at the Supreme Court in Washington, Monday, March 23, 2015. Also shown are Frances Sheehan, left, and Joanne Sheehan, both sisters of Teresa Sheehan. (AP Photo/Molly Riley)

Wrestling with the case of a knife-wielding San Francisco woman who was shot in her room at a group home by city police officers, U.S. Supreme Court justices seemed inclined Monday to give police some leeway in dealing with mentally ill, potentially violent suspects.

When officers are facing someone who is armed and “may be violent at any time,” there is “some reason to give the police officers who have to deal with them the benefit of the doubt,” Justice Elena Kagan told a lawyer for Teresa Sheehan, who survived the 2008 shooting and is suing the city for damages.

The liberal Kagan appeared to be aligned with conservative Justice Antonin Scalia, who — referring to the legal requirement to “reasonably accommodate” a person’s physical or mental disability — declared, “It is never reasonable to accommodate somebody who is armed and violent, period.”

But no clear standard for applying the Americans with Disabilities Act to police confrontations, the central issue in the case, emerged from the one-hour hearing. At least one justice, Sonia Sotomayor, suggested that the law could play a constructive role in avoiding unnecessary harm to the mentally ill.

The ADA, Sotomayor said, was “intended to ensure that police officers try mitigation in these situations before they jump to violence.” The alternative, she said, may be “a society in which the mentally ill are automatically killed,” citing a report that about 350 mentally impaired individuals each year are fatally shot by police in the United States.

In San Francisco, disability-rights groups told the court, more than half of the 19 people fatally shot by police between 2005 and 2013 had psychiatric disabilities. Monday’s hearing took place three weeks after Los Angeles police shot and killed a mentally ill, homeless man who had undergone psychiatric treatment in federal prison before his release last year.

In response to Sotomayor, San Francisco’s lawyer, Deputy City Attorney Christine Van Aken, said the federal disability law was not intended to require measures short of force when officers are at risk.

“If the individual presents a significant threat, then no accommodation is required,” Van Aken told the court. Even if an armed suspect ignored an officer’s command to put his hands up because he was deaf, and the officer knew that, she said, the officer would nevertheless be entitled to shoot the suspect if necessary to “protect public safety.”

Police were summoned to a Mission District group home in August 2008 by a social worker who said Sheehan, a 56-year-old resident who suffered from schizophrenia, had a knife and had threatened to kill him.

Sgt. Kimberly Reynolds and Officer Katherine Holder entered her room and said Sheehan came at them with a knife. They left and called for backup, but re-entered shortly before help arrived, breaking down the door when Sheehan tried to block it. The officers explained later that they feared Sheehan might have access to other weapons or escape from the room.

They tried to subdue her with pepper spray, but she continued to wield the knife, and the officers then shot her five or six times. Sheehan needed two hip-replacement operations because of her wounds, her lawyer said.

She was charged with assault, but a jury deadlocked and prosecutors dropped the case. Her damage suit accuses the police of using excessive force and violating her rights as a disabled person. The suit was dismissed by U.S. District Judge Charles Breyer but reinstated in February 2014 by the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, which said a jury could find the officers’ second entry and subsequent use of force unjustified.

The Supreme Court took up the case primarily to decide how the Americans with Disabilities Act applies to police encounters with the mentally ill. San Francisco, joined by other cities and counties and police organizations, argued that the ADA, which requires government agencies to make allowances for physical and mental impairments in their practices, doesn’t apply to armed suspects whom police consider to be dangerous.

The Obama administration largely sided with San Francisco, arguing that police are justified in using force unless they know the individual poses no threat to the public.

It might be different, Justice Department lawyer Ian Gershengorn told the court, if officers could see the suspect had no chance to escape — for example, if a mentally ill person with a knife was cornered in an alley, or if a security camera had allowed the police to look into Sheehan’s room and had seen her huddled in a corner.

That didn’t satisfy Justice Anthony Kennedy, who told Gershengorn his standard “gives no guidance at all to an officer faced ... with a violent person.”

Sheehan drew allies from disability-rights groups and mental health organizations, who argued that a jury should decide whether she posed a threat and whether the officers could have waited her out, brought in a negotiator or taken other measures without resorting to violence.

“The way to interact with mentally disabled individuals is through communication and time,” said Sheehan’s lawyer, Leonard Feldman. “Police officers know that, and they’re trained that way.”

A ruling is due by the end of June. The case is San Francisco vs. Sheehan, 13-1412.

Bob Egelko is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. E-mail: begelko [at] sfchronicle.com

Twitter: @egelko

Justices skeptical that disability law applies to armed, violent suspects who are mentally ill

http://www.usnews.com/news/politics/articles/2015/03/23/supreme-court-considers-impact-of-disability-law-on-police

<85.jpeg>

This handout photo provided by Patricia C. Sheehan, taken Dec. 25, 2013, shows Teresa Sheehan. The Supreme Court on March 23, 2015, will consider whether police must take special precautions when trying to arrest a person who is mentally ill. The case centers on Teresa Sheehan. Police forced their way into her room at a group home after she threatened her social worker and when she came at them with a knife, officers shot her five times. Lawyers for Sheehan say the Americans With Disabilities Act requires police to make reasonable accommodations when arresting people who have mental or physical disabilities. (AP Photo/Patricia C. Sheehan)

Associated PressMarch 23, 2015 | 3:17 p.m. EDT+ More

BY SAM HANANEL, Associated Press

WASHINGTON (AP) — The Supreme Court on Monday seemed skeptical that the nation's disabilities law requires police to take special precautions when arresting armed and violent suspects who are mentally ill. Most justices expressed doubts about second-guessing police who are trying to protect public safety.

The justices heard arguments in a dispute over how San Francisco police in 2008 dealt with a woman with schizophrenia who had threatened to kill her social worker. Police ultimately forced their way into Teresa Sheehan's room at a group home, then shot her after she came at them with a knife.

Sheehan survived and later sued the city, claiming police had a duty under the Americans with Disabilities Act to consider her mental illness and take more steps to avoid a violent confrontation.

The case comes as police have been criticized for a series of high-profile incidents where suspects with mental illness have been shot and killed — most recently an unarmed, naked man in an apartment complex outside Atlanta.

San Francisco agrees that the ADA requires public officials to make "reasonable accommodations" to avoid discriminating against people with disabilities, but Deputy City Attorney Christine Van Aken told the justices that it doesn't apply "if the individual presents a significant threat."

Justice Antonin Scalia seemed to take the city's side, but he wondered whether the court should have taken up the case in the first place. Scalia grilled Van Aken about why the city seemed to change its legal tack after the high court had agreed to hear the case.

The city originally seemed to claim that the ADA didn't apply at all to police arrests, Scalia said, but later acknowledged that it did apply, except when armed and violent suspects pose a direct threat.

"There's a technical word for this," Scalia said. "It's called bait-and-switch."

Van Aken insisted that the city had consistently argued that there is no accommodation under the ADA "where there are exigent circumstances."

Sheehan's lawyer, Leonard Feldman, said he would welcome it if the court simply dismissed the case and sent it back to the lower courts. Then, a jury could decide whether police should have used less aggressive tactics, such as waiting for backup and trying to talk to her in a nonthreatening way. That's what the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled after a federal district judge initially threw the case out.

"The entire risk that officers confronted was avoidable," Feldman said.

The Obama administration tried to stake out a middle ground. Deputy Solicitor General Ian Gershengorn told the justices that when a mentally ill person is armed and violent, police should only change tactics if the person is "contained and visible."

That didn't seem to satisfy Justice Anthony Kennedy.

"I think the standard you've just proposed gives no guidance at all to an officer faced with a violent person," Kennedy said.

The case has attracted attention from mental health advocates who say that failing to take account of a suspect's disability often results in unnecessary shootings by police. Lower courts have split on when and how the law should apply to police conduct when public safety is at risk.

Law enforcement groups have also weighed in, saying a ruling in Sheehan's favor could undermine police tactics, place officers and bystanders at risk and open them to additional liability.

In Sheehan's case, her social worker called police for help in restraining her so she could be taken to a hospital for treatment. Officers entered her room with a key, but Sheehan threatened them with a knife, so they closed the door and called for backup. But they said they weren't sure whether Sheehan had a way to escape, and were concerned that she might have other weapons inside.

How Police Can Stop Shooting People With Disabilities

https://www.aclu.org/blog/criminal-law-reform-free-speech/how-police-can-stop-shooting-people-disabilities

03/20/2015

Disability Rights

By Claudia Center, Senior Staff Attorney, ACLU at 1:59pm

Hundreds of Americans with disabilities die each year in police encounters, and many more are seriously injured. On Monday, the U.S. Supreme Court will hear oral argument in a case about one of these interactions.

In San Francisco v. Sheehan, police were called to take Teresa Sheehan – a woman having a psychiatric emergency – to the hospital. Instead of helping Ms. Sheehan get treatment, the officers ended up shooting her five times. She survived and sued. At issue is whether and how the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) applies to interactions between police and people with disabilities.

The Supreme Court is weighing in against a backdrop of news stories detailing a seemingly unending stream of officer-involved shootings. The dead and wounded are mostly persons with mental disabilities and young men of color. Many – such as Jason Harrison, Anthony Hill, and Kajieme Powell – are both.

Police shootings of persons with mental disabilities tend to follow a pattern. Someone calls the police about a person in crisis. The police arrive, but the person in crisis fails to immediately follow police commands, not because the person is a “criminal” but because they are experiencing a crisis related to their mental disability.

In response to the person’s noncompliance, the officers start shouting and draw their weapons. They may surround the individual or spray them with mace. The crisis escalates. In a panicked effort to resist, the person grabs a nearby object – a knife, a screwdriver, a pen, a mop. The officers fire. Usually the disabled person dies.

There is a safer way for police to interact with persons with mental disabilities in crisis. In communities across the country, officers are trying to resolve these situations without resort to lethal force by using accepted crisis intervention and de-escalation tools, including calm communication, collaboration with mental health resources, physical containment of the individual from a distance, and patience.

These kinds of strategies should be considered reasonable accommodations under the ADA, as the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled. Their use could have prevented the near-fatal shooting of Ms. Sheehan.

In Ms. Sheehan’s case, the officers knew from the outset that they were dealing with a disability crisis situation. When they found Ms. Sheehan quiet and contained within her room, they had the opportunity to use their crisis intervention training. They could have surveyed the premises, consulted with command on strategies, and used calm communication to try to convince Ms. Sheehan to go with them to the psychiatric hospital.

They didn’t.

Without a clear plan for a safe interaction, the officers entered Ms. Sheehan’s locked second-story room without her permission. Twice. The second time they did so with force, shouting, spraying mace, and with guns drawn. When Ms. Sheehan brandished a bread knife, the officers fired multiple times at close range. She almost died. She spent months in the hospital and rehab and has permanent physical injuries.

The safer strategies are neither expensive nor complicated, but their implementation requires a commitment to change. Law enforcement must adopt ADA-compliant policies, practices, and trainings that require safer policing strategies for people with disabilities and that honestly assess bad outcomes after the fact.

If the Supreme Court rules that Ms. Sheehan somehow is not protected by the ADA, then the decades-long movement to achieve safer police interactions with individuals with disabilities will suffer a devastating setback. Such an outcome could eliminate one of the few legal mandates available to combat the terrible cycle of avoidable police shootings and killings. A call for help shouldn’t result in death.

For more information:

https://soundcloud.com/workweek-radio/ww3-...

Add Your Comments

We are 100% volunteer and depend on your participation to sustain our efforts!

Get Involved

If you'd like to help with maintaining or developing the website, contact us.

Publish

Publish your stories and upcoming events on Indybay.

Topics

More

Search Indybay's Archives

Advanced Search

►

▼

IMC Network