From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

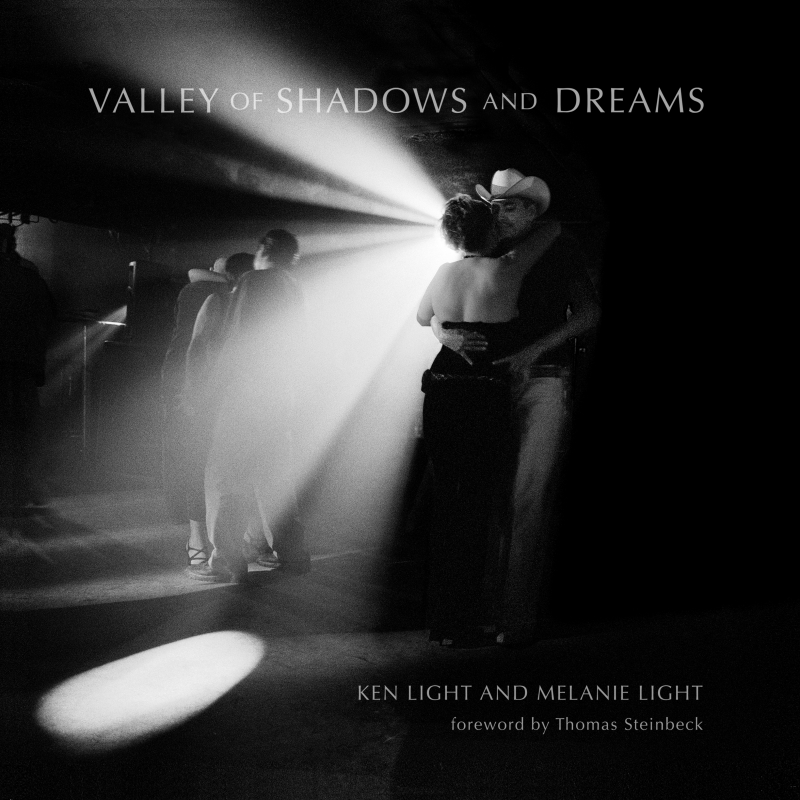

Valley of Shadows and Dreams

I’m always interested to see how other people, who live outside of this area, interpret the political and environmental landscape of Fresno and the Central Valley. Ken and Melanie Light are from the Bay Area and bring such a unique and fresh interpretation of the Valley that I had to share their impressions of the place we call home with Indybay readers. Below is an interview I did with them last month.

Valley of Shadows and Dreams: A Book by Ken and Melanie Light

By Mike Rhodes

Valley of Shadows and Dreams

Text by Melanie Light

Photographs by Ken Light

Foreword by Thomas Steinbeck

Hardcover with flaps, 10 × 10

176 pages with more than 100 black-and-white photographs

ISBN: 978-1-59714-172-7, $40

Photography/Sociology

Publication Month: May 2012

Mike: In the book, you mention water as being an issue that came to your attention. Can you elaborate on that? What did you find out about water that was interesting?

Melanie: The first thing I noticed is that the developers were building lakes in the middle of nowhere and at the same time, we knew there was a chronic water shortage. The farmers are always asking for more water. We were just completely perplexed.

I started digging around to figure out how this works and it gets very complex. A person gets water and they sell their water here, they sell it there, but in the end it seemed like there were no supervising adults in charge of a very precious resource that is dwindling. It is a similar issue globally with rights and this is happening all over the world where the more wealthy and politically connected people are in charge of who gets the water and they are not always the most responsible people with how it is preserved, used and maintained.

One thing I found out was that all of the water is a public trust and that means all of the citizens own it, but the government has given control to a very small group of people and I just find that remarkable. It is a symptom of a national plague that we have weak government.

Mike: I’m always amazed by the fact that Tulare Lake was the largest fresh water lake west of the Mississippi. It was drained for the Boswell cotton farming operation.

Melanie: Yes, theoretically Californians own the water, but there is a small agricultural group who got the federal and state government to build the dams and the aqueduct so that they can control the water. We are paying for that, our tax dollars are paying for that (water), but we don’t get a break on our water prices. Not only that, but I just found out that Fresno didn’t even have a meter water plan until three years ago, whereas we on the coast have been rationed to the hilt every summer. It is so unfair and so inequitable that it is crazy.

The other thing I found out is that we are subsidizing the water and the infrastructure for the water being delivered to agriculture. We are not getting a break on our food prices and the food is being sold on an international market. We are subsidizing food for profit that is going through other countries and to the private pockets of growers. I just find that remarkable. And these are the people who are talking about their rights, their freedom, they don’t want regulation and they don’t like the government. I have to say that the government has been serving them extremely well.

Mike: In addition to water what did you find here that surprised you? What was it about the Central Valley that attracted you here to do this book and were there any surprises?

Ken: There are always surprises. I had photographed in the Central Valley in the late 1970s and early 1980s, so for me it was a kind of revisiting with a more mature vision because I’m more experienced as a photographer. Things that I might have passed by then, all of a sudden came out at me.

It is beautiful, you look up in the sky and it has a very open sky, but then you start seeing people with asthma and you start seeing issues around pesticide usage. I remember one day driving down Highway 5 to come into the Valley and I looked to my right and there was these big machines spraying pesticides. I was probably the only one to stop. People don’t see it. They don’t think about it. I worry about the use of pesticides going on our food, it goes into the water, it goes into the air. One of the things that really surprised me was the dairies.

You sit at home in the Bay Area and you watch TV with the happy cows—milk and cheese from California and they (the cows) are very happy, but then when you go out into the industrial dairies and there is not one blade of grass. That really shocks you. I remember during the summer going out around these dairies. The cows would die and they would just throw the cows alongside the road. That was a shock.

As the downturn in the economy hit, after the boom of the housing market crashed, I began to see more people with problems. I spent a good amount of time in Fresno photographing some of the camps of homeless people that grew. Some of this was chronic homelessness, but it became more visible. Because of the downturn, people became more interested in the issue. I went into these camps where people were desperate for social service support; they were living in wooden shacks. Seeing that was really a shock, and it reminded me of the Great Depression and the Hoovervilles.

Mike: Because of the intensity of poverty in this region, I have heard the Central Valley referred to as the Appalachia of the west. I noticed that the two of you also produced an earlier book about Appalachia in 2006 titled Coal Hollow: Photographs and Oral Histories. Any comparisons between the two areas you would like to share?

Ken: There are a lot of similarities and it was somewhat ironic after having done Coal Hollow. My original intention of going there was to reexamine this seminal part of America that people go back to generation after generation to see “Has America really changed?” What has happened in this region that we know is classically impoverished?

Beginning the project here and then all of a sudden two years into the project we start reading, “Oh, the Central Valley is the new Appalachia,” and we are like, “What?” But there are a lot of similarities because they are both extractive. So, in Appalachia, back east, West Virginia, Kentucky, they take out the coal and with the coal they take out the money, and the money does not go back into the community. It goes to the bankers, the corporations that are not in West Virginia—they are in Boston, New York and they are really about making money.

In the Valley, it is the same way. It is from the ground, it just happens to be fruit and vegetables, etc., on a massive scale, much like coal mining. The same exact thing is happening, and you see people with major health issues and people with bad teeth, people with educational problems. The similarities are quite remarkable and also the poverty levels in which people live.

I would say that the major difference is that coal is on a down slide and has been mechanized, which I guess is what is happening in the Valley, but I went into the coal mines to photograph and where 30 years ago there would have been 200 men working in the mine, now there are 10. They are using a machine and taking more coal out and I guess the same problem will happen in the Valley as more and more machines come in. Despite the hard work that people have laboring in the fields, it does put food on their table and supports their families as they try to move up. Theoretically, those jobs will disappear.

Melanie: Actually, we didn’t even want to do that story when we came to the Valley. When I first came to the Valley, I thought to myself, “Oh my God, it is just like West Virginia,” right down to the whole extractive nature of the work, the parallel histories, everything. I said, “Let’s not do that again.” We really wanted to stick with the housing issue but, of course, all roads lead to Rome and you could not really do it.

The other thing is that it (agriculture) is a mono industry; there is no other industry here, so as one industry shifts and moves toward mechanization there is nobody here being educated, there are no other industries being developed or businesses. The people are really left behind in the same way as human waste. That is tragic. That is sad. It is not only tragic for these people here in this area, it is tragic for the nation that this happens on such a large scale.

Mike: You are from the Bay Area and you have given presentations up there about this book. You did a presentation in Marin recently. How did that go? What is the reaction you get when giving a presentation about the Central Valley? What kind of questions do you get? What do people think about your story?

Melanie: The event in Marin was sponsored by Sustainable San Rafael. One of the most interesting things that came out was this notion of the coastal Californians versus the inland Californians. One of the things I learned in this project is that larger and more important than the divide between north and south, it is really the inland and coastal issue. They were fascinated by that and asked what is the culture of the Valley versus the culture of the coast and how can we join them together. Honestly, my little garden can’t grow enough food to feed me. We all need to be on the same page about how we are going to use this resource to feed our country. That was the most interesting aspect of that event.

For more photos from the book and a longer version of the interview, see: http://fresnoalliance.com/wordpress/?p=5590

*****

Mike Rhodes is the editor of the Community Alliance newspaper. Contact him at editor [at] fresnoalliance.com.

**************

Other comments about the book:

“The more than 100 black-and-white images evoke the topical and the transcendent...Accompanied by informative and urgent essays about the political, environmental, and social challenges facing the region, the book makes a stirring call to change the way we consider the disenfranchised by offering a window into their lives.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Taken in the Central Valley, these stirring black-and-white images channel WPA-era Dorothea Lange through their attention to labor, poverty, immigration, and agriculture.”

—San Francisco Magazine

“In this book you will find a powerful indictment not only of what has happened lately in America’s largest state, but also of what is happening across this country right now. The abuse of illegal immigrants, environmental degradation, the madness of a real estate bubble, and all the other problems of the Central Valley are unfortunately relevant nationwide. Ken and Melanie Light bring great compassion and an eye for beauty to this subject, facing hard truths but refusing to despair.”

—Eric Schlosser, author of Fast Food Nation

By Mike Rhodes

Valley of Shadows and Dreams

Text by Melanie Light

Photographs by Ken Light

Foreword by Thomas Steinbeck

Hardcover with flaps, 10 × 10

176 pages with more than 100 black-and-white photographs

ISBN: 978-1-59714-172-7, $40

Photography/Sociology

Publication Month: May 2012

Mike: In the book, you mention water as being an issue that came to your attention. Can you elaborate on that? What did you find out about water that was interesting?

Melanie: The first thing I noticed is that the developers were building lakes in the middle of nowhere and at the same time, we knew there was a chronic water shortage. The farmers are always asking for more water. We were just completely perplexed.

I started digging around to figure out how this works and it gets very complex. A person gets water and they sell their water here, they sell it there, but in the end it seemed like there were no supervising adults in charge of a very precious resource that is dwindling. It is a similar issue globally with rights and this is happening all over the world where the more wealthy and politically connected people are in charge of who gets the water and they are not always the most responsible people with how it is preserved, used and maintained.

One thing I found out was that all of the water is a public trust and that means all of the citizens own it, but the government has given control to a very small group of people and I just find that remarkable. It is a symptom of a national plague that we have weak government.

Mike: I’m always amazed by the fact that Tulare Lake was the largest fresh water lake west of the Mississippi. It was drained for the Boswell cotton farming operation.

Melanie: Yes, theoretically Californians own the water, but there is a small agricultural group who got the federal and state government to build the dams and the aqueduct so that they can control the water. We are paying for that, our tax dollars are paying for that (water), but we don’t get a break on our water prices. Not only that, but I just found out that Fresno didn’t even have a meter water plan until three years ago, whereas we on the coast have been rationed to the hilt every summer. It is so unfair and so inequitable that it is crazy.

The other thing I found out is that we are subsidizing the water and the infrastructure for the water being delivered to agriculture. We are not getting a break on our food prices and the food is being sold on an international market. We are subsidizing food for profit that is going through other countries and to the private pockets of growers. I just find that remarkable. And these are the people who are talking about their rights, their freedom, they don’t want regulation and they don’t like the government. I have to say that the government has been serving them extremely well.

Mike: In addition to water what did you find here that surprised you? What was it about the Central Valley that attracted you here to do this book and were there any surprises?

Ken: There are always surprises. I had photographed in the Central Valley in the late 1970s and early 1980s, so for me it was a kind of revisiting with a more mature vision because I’m more experienced as a photographer. Things that I might have passed by then, all of a sudden came out at me.

It is beautiful, you look up in the sky and it has a very open sky, but then you start seeing people with asthma and you start seeing issues around pesticide usage. I remember one day driving down Highway 5 to come into the Valley and I looked to my right and there was these big machines spraying pesticides. I was probably the only one to stop. People don’t see it. They don’t think about it. I worry about the use of pesticides going on our food, it goes into the water, it goes into the air. One of the things that really surprised me was the dairies.

You sit at home in the Bay Area and you watch TV with the happy cows—milk and cheese from California and they (the cows) are very happy, but then when you go out into the industrial dairies and there is not one blade of grass. That really shocks you. I remember during the summer going out around these dairies. The cows would die and they would just throw the cows alongside the road. That was a shock.

As the downturn in the economy hit, after the boom of the housing market crashed, I began to see more people with problems. I spent a good amount of time in Fresno photographing some of the camps of homeless people that grew. Some of this was chronic homelessness, but it became more visible. Because of the downturn, people became more interested in the issue. I went into these camps where people were desperate for social service support; they were living in wooden shacks. Seeing that was really a shock, and it reminded me of the Great Depression and the Hoovervilles.

Mike: Because of the intensity of poverty in this region, I have heard the Central Valley referred to as the Appalachia of the west. I noticed that the two of you also produced an earlier book about Appalachia in 2006 titled Coal Hollow: Photographs and Oral Histories. Any comparisons between the two areas you would like to share?

Ken: There are a lot of similarities and it was somewhat ironic after having done Coal Hollow. My original intention of going there was to reexamine this seminal part of America that people go back to generation after generation to see “Has America really changed?” What has happened in this region that we know is classically impoverished?

Beginning the project here and then all of a sudden two years into the project we start reading, “Oh, the Central Valley is the new Appalachia,” and we are like, “What?” But there are a lot of similarities because they are both extractive. So, in Appalachia, back east, West Virginia, Kentucky, they take out the coal and with the coal they take out the money, and the money does not go back into the community. It goes to the bankers, the corporations that are not in West Virginia—they are in Boston, New York and they are really about making money.

In the Valley, it is the same way. It is from the ground, it just happens to be fruit and vegetables, etc., on a massive scale, much like coal mining. The same exact thing is happening, and you see people with major health issues and people with bad teeth, people with educational problems. The similarities are quite remarkable and also the poverty levels in which people live.

I would say that the major difference is that coal is on a down slide and has been mechanized, which I guess is what is happening in the Valley, but I went into the coal mines to photograph and where 30 years ago there would have been 200 men working in the mine, now there are 10. They are using a machine and taking more coal out and I guess the same problem will happen in the Valley as more and more machines come in. Despite the hard work that people have laboring in the fields, it does put food on their table and supports their families as they try to move up. Theoretically, those jobs will disappear.

Melanie: Actually, we didn’t even want to do that story when we came to the Valley. When I first came to the Valley, I thought to myself, “Oh my God, it is just like West Virginia,” right down to the whole extractive nature of the work, the parallel histories, everything. I said, “Let’s not do that again.” We really wanted to stick with the housing issue but, of course, all roads lead to Rome and you could not really do it.

The other thing is that it (agriculture) is a mono industry; there is no other industry here, so as one industry shifts and moves toward mechanization there is nobody here being educated, there are no other industries being developed or businesses. The people are really left behind in the same way as human waste. That is tragic. That is sad. It is not only tragic for these people here in this area, it is tragic for the nation that this happens on such a large scale.

Mike: You are from the Bay Area and you have given presentations up there about this book. You did a presentation in Marin recently. How did that go? What is the reaction you get when giving a presentation about the Central Valley? What kind of questions do you get? What do people think about your story?

Melanie: The event in Marin was sponsored by Sustainable San Rafael. One of the most interesting things that came out was this notion of the coastal Californians versus the inland Californians. One of the things I learned in this project is that larger and more important than the divide between north and south, it is really the inland and coastal issue. They were fascinated by that and asked what is the culture of the Valley versus the culture of the coast and how can we join them together. Honestly, my little garden can’t grow enough food to feed me. We all need to be on the same page about how we are going to use this resource to feed our country. That was the most interesting aspect of that event.

For more photos from the book and a longer version of the interview, see: http://fresnoalliance.com/wordpress/?p=5590

*****

Mike Rhodes is the editor of the Community Alliance newspaper. Contact him at editor [at] fresnoalliance.com.

**************

Other comments about the book:

“The more than 100 black-and-white images evoke the topical and the transcendent...Accompanied by informative and urgent essays about the political, environmental, and social challenges facing the region, the book makes a stirring call to change the way we consider the disenfranchised by offering a window into their lives.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Taken in the Central Valley, these stirring black-and-white images channel WPA-era Dorothea Lange through their attention to labor, poverty, immigration, and agriculture.”

—San Francisco Magazine

“In this book you will find a powerful indictment not only of what has happened lately in America’s largest state, but also of what is happening across this country right now. The abuse of illegal immigrants, environmental degradation, the madness of a real estate bubble, and all the other problems of the Central Valley are unfortunately relevant nationwide. Ken and Melanie Light bring great compassion and an eye for beauty to this subject, facing hard truths but refusing to despair.”

—Eric Schlosser, author of Fast Food Nation

For more information:

http://valleyofshadowsanddreams.com/

Add Your Comments

We are 100% volunteer and depend on your participation to sustain our efforts!

Get Involved

If you'd like to help with maintaining or developing the website, contact us.

Publish

Publish your stories and upcoming events on Indybay.

Topics

More

Search Indybay's Archives

Advanced Search

►

▼

IMC Network